A Network State of 100 British Charter Cities Across The World

Over 10 years, Britain could establish 100 Hong Kongs as a peripheral global network state, each chokepoint a node in a thin empire for the price of a single day of NHS spending. The Five Keys that lock up the world become a hundred, bringing technology and aid to the undeveloped corners of Earth.

The British Empire did not begin with flags planted in foreign soil or armies marching across continents. It began with account books, shipping manifests, and contracts signed in counting houses. The greatest empire the world has ever seen was, at its origin, a commercial venture run by merchants who wanted to make money, not history.

This matters because it reveals something most people have forgotten: empire is not about territory. It never was. The secret which made Britain master of the world was not the size of its army or the extent of its lands. It was something far more elegant and far more lethal. Britain understood that power flows through chokepoints, and whoever controls the chokepoints controls everything that passes through them.

A pattern has repeated itself across five centuries. If Britain once built an empire through trading posts, chartered companies, and strategic ports, could it do so again? Not through conquest, but through contract. Not through domination, but through services rendered. A network of one hundred Hong Kongs, scattered across the globe, each one a node in a new kind of sovereignty—thin, lawful, and devastatingly effective.

The Ordinary Merchant Adventurers

By the late sixteenth century, Spain and Portugal had carved up much of the known world between them. They had the Pope's blessing, vast armies, and a head start of nearly a century. England was a second-rate power clinging to the edge of Europe, with no standing army to speak of, empty coffers, and a monarch who could barely pay her own sailors. The Treaty of Tordesillas had divided the non-Christian world between the Iberian powers in 1494, and England had no seat at that table.

So England did something different. Rather than attempting conquest, the Crown issued royal charters to groups of merchants, granting them monopolies over trade in specific regions. These chartered companies could build forts, establish settlements, raise private armies, mint currency, and administer justice. They were legally private but functionally sovereign—hybrid creatures who existed somewhere between commerce and statecraft.

The structure was elegant in its simplicity. The Crown risked nothing; it merely granted permission and collected duties. The merchants risked their capital but gained exclusive access to potentially lucrative markets. If the venture failed, the loss was private. If it succeeded, the profits were shared and the Crown gained strategic footholds without deploying a single soldier from the royal payroll.

The East India Company received its charter in 1600. The Virginia Company followed in 1606. The Hudson's Bay Company in 1670. The Royal African Company in 1660. These were not colonies in any conventional sense. They were commercial footholds, designed to extract profit rather than to plant civilisations.

The pattern was always the same. First came a coastal trading post, positioned at a strategic harbour or river mouth. Minimal land, minimal administration, maximum commercial utility. These were called factories—not in the industrial sense, but from factor, meaning agent or trader. A factor was an agent who conducted business on behalf of his principals, and a factory was simply the place where factors worked.

Surat, Madras, Calcutta, Bombay—each began as little more than a warehouse with a flag. The factory at Surat, established in 1612, consisted of a few buildings where English merchants stored cotton textiles and indigo while waiting for the monsoon winds to carry their ships home. There was no grand plan for territorial expansion. There was only the need for a secure place to store goods and conduct transactions.

Over time, the warehouses became forts. The forts became cities. Company officials found themselves settling disputes between merchants—first between their own countrymen, then between their countrymen and local traders, and finally between local traders themselves who preferred English arbitration to the unpredictable justice of Mughal governors. They collected taxes to pay for the walls that protected the goods. They backed local rulers against their rivals in exchange for trading concessions. Trade pulled them inexorably into politics, and politics demanded force, and force required governance.

The transformation was neither planned nor desired. The East India Company's directors in London repeatedly cautioned their agents against territorial entanglement. Territory meant expense, responsibility, and the risk of conflict with powers far stronger than a company of merchants. But the logic of commerce was relentless. Every trading post needed protection. Every protection required negotiation with local powers. Every negotiation created obligations and dependencies. Every dependency, sooner or later, became a crisis that could only be resolved through deeper involvement.

The Battle of Plassey in 1757 is usually marked as the moment the East India Company became a territorial power, but it was less a deliberate conquest than a desperate improvisation. Robert Clive backed one Mughal faction against another, won a battle that was more bribery than combat, and suddenly found himself responsible for the revenues of Bengal. The Company had not set out to rule twenty million people. It had set out to protect its trading position, and ruling twenty million people turned out to be what that required.

By the time Parliament realised what had happened, the Company was administering vast territories, commanding armies larger than those of most European states, and generating revenues that dwarfed the Crown's own income from trade. The Regulating Act of 1773 was the first attempt to bring this strange entity under political control. The India Act of 1784 created a Board of Control to oversee Company policy. The Charter Act of 1813 ended the Company's trade monopoly. Finally, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Crown assumed direct rule and the Company was dissolved entirely.

The entire arc—from trading post to factory to fortified settlement to territorial administration to formal Crown colony—took 257 years. It was never planned. It emerged from the accumulated logic of commerce, security, and political entanglement. Empire followed fait accompli, not design.

Lesson learned and secret revealed - let the ordinary English out of the cage to do business, and they take over the world.

The Five Keys to the World

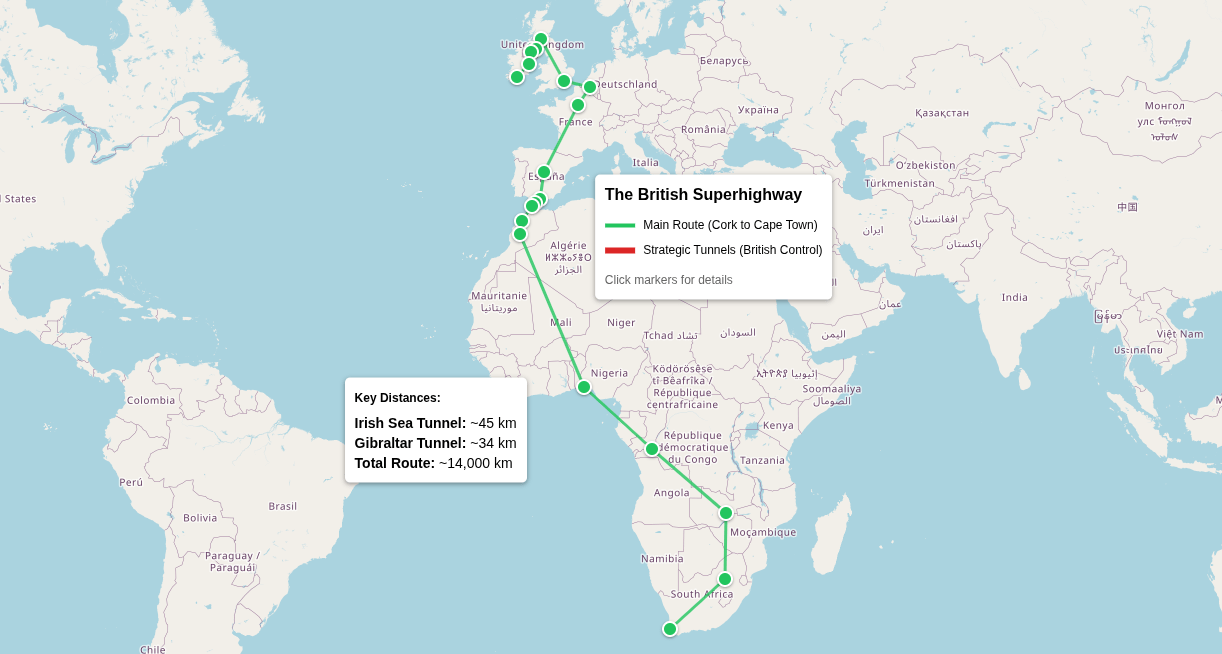

There is a phrase that once circulated in British strategic circles: the five keys that lock up the world. Dover, Gibraltar, the Cape of Good Hope, Alexandria (later superseded by Suez), and Singapore.

Whoever held these points held the arteries of global commerce. Everything else was hinterland.

This is the insight which separates empires that endure from empires which collapse under their own weight. Mass is secondary. Control points are decisive. You do not need to own a continent if you can decide who may cross it. You do not need a vast army if you can starve your enemy's army by closing a strait.

The geography is stark. The Suez Canal, opened in 1869, reduced the voyage from London to Bombay from 11,600 miles around the Cape to 6,200 miles through the Mediterranean—a savings of nearly half the distance, half the time, and half the coal.

Within a decade, Britain had purchased a controlling stake in the Canal Company from the bankrupt Khedive of Egypt. Within two decades, Britain had occupied Egypt outright. The excuse was financial irregularity and the need to protect bondholders. The reality was whoever controlled Suez controlled the route to India, and India was the jewel that made everything else worthwhile.

Gibraltar, seized in 1704, commands the western entrance to the Mediterranean. Every ship passing between the Atlantic and the inland sea must transit within range of its guns. Britain held it against Spanish sieges, French threats, and eventually EU pressure, because losing Gibraltar would mean losing the ability to lock or unlock the Mediterranean at will.

The Cape of Good Hope served a different function: redundancy. If Suez were ever closed—as it was during the Napoleonic Wars, both World Wars, and the Suez Crisis of 1956—the Cape offered an alternative route to Asia. Longer, more expensive, but available. Britain acquired the Cape from the Dutch during the French Revolutionary Wars precisely because Napoleon's control of the Netherlands made the Dutch East Indies route suddenly hostile. Strategic depth required controlling the fallback as well as the primary route.

Singapore's position is almost absurdly advantageous. The Malacca Strait, between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. More than 25 percent of all global trade passes through it. The strait is narrow enough that shore-based artillery could, in an earlier era, close it entirely; narrow enough that a naval squadron could interdict any vessel attempting passage; narrow enough that whoever sits at its southern tip controls access between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Stamford Raffles understood this when he established the trading post in 1819. The Dutch controlled the northern approach at Malacca. The Dutch controlled the eastern archipelago. But neither the Dutch nor anyone else controlled the swampy island at the tip of the peninsula. Raffles saw what others missed: that the island's emptiness was its advantage. No existing power structure to negotiate with, no entrenched interests to overcome, no population to administer. Just a point on a map that happened to sit at the crossroads of maritime Asia.

Britain, a small island with a modest population, ruled the largest empire in human history not by garrisoning every village but by controlling the points through which everything had to pass. The Royal Navy did not need to defeat every enemy fleet; it needed only to be present at the places that mattered. The rest of the world could be left to manage itself, provided the chokepoints remained in British hands.

Why Sheer Land Mass Fails

This explains something that has puzzled strategists for centuries: why do large land empires keep failing?

The pattern is remarkably consistent. A continental power assembles vast territories, enormous populations, and formidable armies. It appears invincible. And then it loses to a smaller, more mobile adversary that never tries to match its strength directly but instead cuts its supply lines, blocks its access to trade, and waits for internal contradictions to do the rest.

Persia under Xerxes commanded an empire stretching from Egypt to Central Asia. The Greek city-states could not possibly match its armies in open battle. But the Greeks did not need to match Persian armies. They needed to hold Thermopylae long enough to prove that mass could be negated by position, and then to destroy the Persian fleet at Salamis. Without naval supremacy, Persia could not supply an army of occupation in Greece. Without an army of occupation, all the territory in the world was useless.

Spain in the sixteenth century controlled more territory than any European power since Rome. Spanish silver from the Americas financed armies that seemed unstoppable. But Spain could not defend its treasure fleets against English raiders. It could not prevent Dutch merchants from undercutting Spanish trade. It could not keep its supply lines open across three oceans simultaneously. The treasure flowed in, but the costs of empire flowed out faster, and by 1600 Spain was bankrupting itself defending possessions it could not afford to lose.

Germany in both World Wars possessed the most formidable army in Europe. German industry could produce weapons at a rate that matched or exceeded its adversaries. German soldiers fought with skill and determination that few could equal. But Germany could not break the British blockade in the First World War, and starvation eventually broke German morale more thoroughly than any battle. In the Second World War, Germany could not knock Britain out of the war before American resources arrived, because Britain was an island that could be supplied by sea, and Germany could not control the sea.

The Soviet Union controlled the largest contiguous territory of any state in history. Its armies could roll across Europe in weeks. Its nuclear arsenal could destroy any adversary. But the Soviet Union could not feed its own people without importing grain. It could not manufacture consumer goods that anyone wanted to buy. It could not generate the wealth to sustain its military commitments. When the economy collapsed, the empire collapsed with it, and no number of tanks could prevent the dissolution.

China today understands this dilemma better than any of the failed land empires that preceded it. Chinese strategists speak constantly about the "Malacca Dilemma"—the fact that roughly 80 percent of China's oil imports pass through a strait that China does not control. The Belt and Road Initiative is, among other things, an attempt to build alternative supply routes: pipelines through Central Asia, railways through Pakistan, ports in the Indian Ocean. If Malacca could be bypassed, Chinese strategists believe, then China would no longer be vulnerable to blockade.

But the geography is unforgiving. Every alternative route is longer, more expensive, and passes through territory that is difficult or impossible to secure. The pipelines require cooperation from Russia and the Central Asian states, cooperation which cannot be guaranteed in a crisis. The railways require passage through some of the most unstable regions on earth. The ports require naval protection that China is only beginning to develop.

This is why China remains obsessed with sea denial—the ability to prevent American naval forces from operating in the Western Pacific—rather than sea control. China does not expect to command the oceans the way Britain once did. It hopes merely to raise the costs of American intervention high enough America will choose not to intervene. It is a defensive strategy born of geographic weakness, and it reveals the fundamental truth land powers can never escape: armies can march, but they cannot swim.

Lesson learned: if Britain wants to kneecap China, all she need do as a small island is control Malacca.

The Venom of Small Creatures

The analogy which captures this principle is biological. Large empires behave like elephants: impressive, powerful, and slow. They can crush opposition through sheer weight. But they are also dependent on continuous intake of resources, vulnerable to any disruption of their supply lines, and incapable of rapid adaptation to changing circumstances.

Maritime powers behave like venomous creatures: small, fast, and capable of paralysing something a hundred times their size by striking precisely at the nervous system. The black mamba does not try to wrestle its prey to the ground. It delivers a single bite and waits for systemic failure. The box jellyfish does not chase its victims. It waits at the chokepoint where fish must pass and injects a toxin that stops the heart within minutes.

At Thermopylae, Leonidas did not try to defeat Persia. He reduced a continental empire to a corridor, made numbers irrelevant, and turned mass into congestion. Three hundred men held a passage because the passage was all that mattered. The Persians could not outflank the position because the mountains were impassable. They could not overwhelm it with numbers because the frontage was too narrow for numbers to matter. They could only wait and hope for treachery—which, eventually, they received.

The lesson was not lost on subsequent strategists. Chokepoints transform the balance of power. A defender at a narrow passage can hold against odds that would be suicidal in open terrain. An attacker must either force the passage at enormous cost or find an alternative route—and if no alternative route exists, the attacker must give up or pay the price.

This is naval chokepoint logic translated to human terrain. And it applies with equal force to commerce. A port at a critical strait can charge tolls which would be extortionate anywhere else, because the alternative—sailing around a continent—is even more expensive. A legal jurisdiction at a crossroads of trade can attract business from every direction, because merchants will always prefer a neutral, predictable venue to one that favours any particular party.

Once circulation is interrupted, everything downstream fails. Trade collapses. Factories fall idle for want of raw materials. Armies starve for want of supplies. Governments lose revenue. Populations grow restless. The kill is systemic, not kinetic. The blockade of Germany in the First World War killed no one directly; it simply prevented food from reaching German cities, and the consequences followed inevitably.

This is why ports matter more than provinces. Why treaties matter more than flags. Why law matters more than ideology. A state that controls the points of circulation can shape the behaviour of states that control vastly more territory, because territory without access is merely a prison.

What Is A Network State?

A network state is a sovereign-aspiring community which begins not with territory, but with people—linked by shared values, law, capital, and coordination—who organise digitally first and acquire physical presence later. Unlike the nation-state, which derives legitimacy from borders conquered or inherited, the network state derives legitimacy from voluntary partnership, exit rights, and functional competence. It starts as a cloud polity: a distributed network with its own governance rules, identity systems, dispute resolution, capital flows, and social contracts, capable of acting coherently across jurisdictions before it controls land.

The term was popularised by Coinbase CTO Balaji Srinivasan in his book "The Network State: How To Start a New Country." It beautifully angered all the right people and was denounced by the worst.

The idea did not emerge in a vacuum. It sits at the junction of earlier traditions: medieval charter cities and trading leagues, religious diasporas, joint-stock companies like the East India Company, and 20th-century special economic zones. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, open-source movements, cryptocurrencies, online churches, remote-first firms, and DAOs—demonstrated large, disciplined populations could coordinate globally without shared geography. Srinivasan controversially – perhaps naively – argued legitimacy, scale, and cohesion could now be built online first, then translated into physical reality through treaties, leases, and legal recognition rather than conquest.

In practical terms, a network state begins as a highly active online community with clear membership criteria, governance, and shared purpose. It then develops real economic weight—companies, capital, infrastructure, and talent pipelines—followed by physical footholds: campuses, charter cities, free ports, leased districts, or special administrative zones embedded within existing states. These are not colonies but contractual presences, stacking territory rather than seizing it. Estonia’s e-residency programme, Dubai’s free zones, Próspera in Honduras, and seasteading or charter-city experiments all illustrate fragments of the model, even if none yet fully qualify as network states in the strong sense.

What distinguishes the network state is competition through governance rather than force. Citizenship is opt-in, law is modular, and loyalty is earned by performance. People join not because they were born somewhere, but because the system works better for them. In this sense, the network state is less a rebellion against the nation-state than a market correction to its failures: a new kind of polity scaled by bandwidth, trust, and coordination—where legitimacy flows from consent, competence, and connection rather than from lines on a map.

What Made Hong Kong Work

Hong Kong was not magic. It was not Chinese industriousness or British virtue or some ineffable spirit of commerce. It was a bundle of guarantees, deliberately assembled and ruthlessly maintained. Its story is best captured in the biography of its financial administrator, Sir John James Cowperthwaite.

Predictable common-law courts. Free capital movement. Neutral port status. External security guarantee. World-class logistics. Global connectivity. Everything else—the skyline, the population, the industries which emerged—was secondary. The foundation was legal, not cultural.

What Britain exported to Hong Kong was not civilisation in any grandiose sense. It was an operating system: a set of rules that made commerce frictionless and outcomes predictable. Merchants from Canton, Bombay, London, and New York could meet on neutral ground, sign contracts enforceable by impartial courts, and trust that their goods and their money would be protected by something more reliable than any single ruler's whim.

The components of this operating system were specific and reproducible.

- The first component was legal predictability. Hong Kong operated under English common law, which meant the principles governing commercial transactions were the same as those governing transactions in London, New York, Singapore, and a dozen other financial centres. A merchant from Shanghai might not speak English, but his lawyer could advise him on the likely outcome of any dispute because the rules were written down, the precedents were available, and the judges were professionals who applied the law impartially. This was not universally true in the nineteenth century. Most legal systems were either unpredictable, corrupt, or biased in favour of local interests. English law offered a neutral alternative.

- The second component was free capital movement. Money could enter Hong Kong from anywhere in the world and leave again without restriction. There were no exchange controls, no limits on repatriation of profits, no requirements to invest locally. This made Hong Kong attractive to anyone with capital to deploy, because capital trapped is capital wasted. Chinese entrepreneurs fleeing instability on the mainland knew their money was safe in Hong Kong. British investors knew they could withdraw their funds if circumstances changed. The absence of restrictions was itself the attraction.

- The third component was neutral port status. Hong Kong did not discriminate between nationalities or flags. Any ship could enter the harbour, any cargo could be unloaded, any merchant could conduct business. The port served commerce, not politics. This neutrality was commercially indispensable. A port that favoured British merchants over American merchants, or Chinese merchants over Japanese merchants, would lose business to competitors who did not discriminate. Hong Kong's commitment to openness was not idealism; it was competitive strategy.

- The fourth component was the external security guarantee. The Royal Navy ensured Hong Kong could not be blockaded, invaded, or intimidated by any regional power. The garrison was small—Hong Kong was never defensible against a determined attack by a great power—but the guarantee was credible because an attack on Hong Kong was an attack on British interests, and Britain would respond. This security umbrella allowed commerce to flourish without the distraction of local defence expenditure or the uncertainty of military vulnerability.

- The fifth component was logistics infrastructure. Hong Kong developed one of the finest natural harbours in Asia, capable of handling the largest vessels afloat. Warehousing, transhipment, ship repair, chandlery, banking, insurance—the entire ecosystem of services a port requires emerged because the other components made long-term investment attractive. Merchants who trusted the legal system were willing to build warehouses. Bankers who trusted the currency regime were willing to extend credit. Insurers who trusted the security guarantee were willing to underwrite cargoes.

The result was a virtuous cycle.

- Good institutions attracted commerce.

- Commerce attracted capital.

- Capital funded infrastructure.

- Infrastructure made commerce more efficient.

- Efficiency attracted more commerce.

The flywheel, once started, built momentum on its own.

Singapore followed the same formula. When Stamford Raffles established the port in 1819, he designed it from the first day as a free port with no tariffs, governed by English commercial law, open to traders of every nation and none. It offered no natural resources, no agricultural wealth, no strategic depth.

What it offered was certainty—and certainty is worth more than gold to anyone whose livelihood depends on goods arriving where they are supposed to arrive.

The Dutch had been in the region for two centuries, but their ports charged tariffs, imposed restrictions, and served the interests of the Dutch East India Company rather than commerce in general. Singapore undercut them overnight simply by removing friction. A ship could arrive, unload, reload, and depart without paying a single guilder in customs duties. Within a decade it was the dominant entrepôt of Southeast Asia. Within a generation it was indispensable.

This is the formula.

- Find a chokepoint.

- Establish a legal regime that traders can trust.

- Remove barriers to entry.

- Provide security without domination.

- Get out of the way and collect the rents as wealth pours through.

The Wider Pattern Across Empire

Aden, Colombo, Cape Town, Penang, the Shanghai International Settlement—each followed variations of the same pattern. They succeeded not because Britain conquered their hinterlands but because Britain made them useful in ways that no local power could match. They were platforms, not possessions.

Aden was acquired in 1839 as a coaling station for steamships on the route to India. It had no hinterland to speak of—just barren mountains and hostile tribes. But it sat at the entrance to the Red Sea, which meant it sat at the approach to Suez, which meant it sat on the main artery between Europe and Asia. Ships needed coal, and Aden supplied it. Ships needed repairs, and Aden provided them. Ships needed provisions, and Aden's merchants sourced them from across the region. The port became indispensable not because of what it produced but because of where it was.

Colombo developed as the hub of South Asian transhipment. British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) produced tea and rubber, but Colombo's importance transcended its hinterland. Ships on the India-to-Singapore route could stop at Colombo, offload cargo bound for East Africa or the Persian Gulf, pick up cargo bound for Malaya or China, and continue their voyage. The port earned fees on cargo it never owned, from trade routes it did not control. It was pure intermediation.

Cape Town began as a victualling station for the Dutch East India Company. When Britain acquired it during the Napoleonic Wars, it became the pivot point for British trade with Asia. Ships rounding the Cape needed to stop for water, provisions, and repairs. The voyage from Europe to India or China was long enough crews sickened, stores ran low, and hulls needed attention. Cape Town provided all three, and charged accordingly.

Penang, off the northwest coast of Malaya, was acquired in 1786 as Britain's first territorial foothold in Southeast Asia. It was intended as a counter to Dutch dominance of the spice trade and as a repair station for vessels on the India-to-China route. Like Singapore after it, Penang was a free port from the beginning—no tariffs, no restrictions, open to all. It thrived until Singapore eclipsed it, and even then it remained a useful secondary node in the network.

The Shanghai International Settlement was perhaps the strangest of all. It was not a British colony; it was a treaty port, governed by a municipal council drawn from the foreign merchants who lived there, operating under a hybrid legal regime that mixed English law, American law, and French law according to the nationality of the parties. The Chinese government retained nominal sovereignty but exercised no practical control within the settlement. It was extraterritoriality taken to its logical extreme: a city within a city, governed by its foreign inhabitants, subject to laws of their own making.

And it worked. By the 1920s, Shanghai was the most dynamic commercial city in East Asia. Its banks financed trade across the Pacific. Its factories produced textiles for export to the world. Its port handled more cargo than any other in China.

The International Settlement was tiny—barely a few square miles—but it punched so far above its weight it distorted the entire Chinese economy.

What these places shared was not British culture or British settlers or British doctrine. What they shared was a structure—a set of institutions which made commerce predictable, profitable, and safe. The structure could be transplanted to almost any location with adequate geography and willing partners. It did not require conquest or occupation or the paraphernalia of traditional empire. It required only a charter, a court, a port, and a flag.

The Neural Network: 100 New Hong Kongs

Now imagine this pattern extended, systematised, and adapted for the twenty-first century. Not an empire of red on the map, but a network of nodes connected by law, logistics, and mutual benefit. A hundred Hong Kongs, scattered across the Atlantic, the Pacific, the Indian Ocean, the Arctic. Each one sovereign in its commercial affairs, each one linked to the others by shared legal standards, each one offering the same guarantee: if you do business here, the rules are clear, the courts are fair, and your property is safe.

The locations almost select themselves.

Look for places which:

- Sit on major shipping routes;

- Lack the institutional capacity to develop themselves, which would benefit enormously from infrastructure they cannot finance;

- Have historical or legal ties to British traditions;

- Have coastlines with deep-water access;

- Sparse populations, and...

- Governments desperate enough for development that they will accept terms no wealthy state would tolerate.

The Atlantic Corridor

The Atlantic is where Britain's strategic imagination has always lived. It was the Atlantic which connected Britain to the Americas, to Africa, to the riches of the New World. And it is the Atlantic offering some of the most compelling opportunities for charter-port development.

Guyana has emerged as one of the world's fastest-growing economies, thanks to massive offshore oil discoveries. But Guyana lacks the ports, the legal infrastructure, and the financial systems to fully capitalise on its newfound wealth. Its existing harbour at Georgetown is shallow, congested, and inadequate for the vessels modern oil logistics require. A new deep-water port, developed under charter terms, could transform Guyana into the premier logistics hub of the northern South American coast. The port would serve not only Guyana's oil exports but also the trade of landlocked neighbours—the dream of turning the Essequibo into a commercial artery connecting the Amazon basin to the Atlantic.

Angola sits at the junction of African resources and Brazilian markets. The South Atlantic is increasingly important as trade between Africa and South America grows, and Angola occupies a commanding position on its eastern shore. Portuguese legal heritage offers some foundation for commercial law, though decades of civil war and petroleum-fuelled corruption have degraded institutions severely. A charter port on the Angolan coast—perhaps at Lobito, terminus of the Benguela Railway which once connected the Congolese copperbelt to the sea—could revive a trade route dormant for fifty years.

Ghana offers something rare in West Africa: relative political stability and an existing legal system based on English common law. The Gulf of Guinea is increasingly important for oil and gas, and Nigeria's chaos makes Ghana an attractive alternative. A charter port at Takoradi or Tema could serve as the legal and financial hub for West African commerce, providing the predictable courts and transparent regulations Nigeria cannot offer.

Namibia presents an intriguing possibility. Its coastline is long, its population sparse, its deep-water port at Walvis Bay adequate but underutilised. Namibia already serves as a transit corridor for landlocked neighbours—Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe—but infrastructure bottlenecks limit throughput. A charter port could serve the entire southern African interior, competing with South African ports that are plagued by inefficiency and congestion.

The Caribbean Remnants

The Caribbean already contains the fragments of the old imperial network, and several territories remain under British sovereignty. The question is whether these existing possessions could be developed more intensively, and whether additional nodes could be established.

Belize occupies a quiet but strategically potent position on the western edge of the Caribbean, facing the Atlantic trade lanes while sitting at the hinge between Central America and the Gulf of America. It is one of the few mainland states in the region with English common law, a parliamentary system, and a deep cultural familiarity with British institutions—yet it remains economically underdeveloped, under-portified, and chronically constrained by scale. Belize City’s port is shallow and exposed, unsuitable for modern container traffic or serious transshipment, while regional trade is funnelled instead through congested hubs like Panama, Kingston, and Miami.

A charter port on the Belizean coast—purpose-built, deep-water, and legally insulated—could transform the country into a Caribbean logistics and services node linking Central America, the Yucatán, and Atlantic shipping routes. Such a port would not compete with Panama’s canal economics, but complement them: serving as a finance, arbitration, warehousing, and light-manufacturing hub for regional trade that currently lacks neutral, predictable legal infrastructure. For Belize, the prize would be profound: diversified revenue beyond tourism, upgraded infrastructure, and a durable role as a small but indispensable connector state in the Atlantic system.

The Turks and Caicos Islands already function as an offshore financial centre, but their potential as a logistics hub remains underdeveloped. The islands sit at the eastern entrance to the Caribbean basin, within easy reach of the American East Coast and the major shipping lanes connecting North America to South America. A deep-water transhipment port could position Turks and Caicos as a Caribbean equivalent of Singapore—a neutral hub where cargo changes vessels without entering any country's customs jurisdiction.

Bermuda already hosts one of the world's largest insurance and reinsurance markets. What it lacks is significant port infrastructure. Development is constrained by environmental sensitivity and the islands' small size, but targeted investment could strengthen Bermuda's position as an Atlantic logistics node, particularly for high-value, time-sensitive cargo.

The British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands are financial centres without significant physical trade, but their legal infrastructure is already world-class. They could serve as administrative headquarters for the network, handling corporate registration, arbitration, and financial services while other nodes handle physical logistics.

The Indo-Pacific Arc

The Indo-Pacific is where the strategic stakes are highest and where the network would face the greatest geopolitical challenges. China's Belt and Road Initiative is already reshaping port infrastructure across the region, and any British-led alternative would face both competition and potential hostility.

The Philippines commands some of the most strategically significant waters on earth. The Luzon Strait connects the South China Sea to the Pacific Ocean; the San Bernardino Strait connects the Pacific to the Philippine archipelago's interior seas. American bases already dot the islands, but commercial port infrastructure remains underdeveloped. A charter port in the Philippines—perhaps at Subic Bay, site of the former American naval base—could serve as the eastern anchor of an Indo-Pacific network, providing an alternative to Chinese-dominated ports further south.

Papua New Guinea offers geography that China desperately wants and Western powers should not concede. The Solomon Sea and the Coral Sea are the approaches to Australia; whoever controls the straits of Papua New Guinea controls access to the entire Australian continent. Port Moresby is already a significant harbour, but it lacks the infrastructure and institutions which would make it a major commercial hub. A charter port could develop Papua New Guinea's potential while ensuring China does not gain the foothold it seeks.

Sri Lanka has already discovered the perils of Belt and Road investment. The Hambantota port, built with Chinese loans, is now operated by China on a 99-year lease after Sri Lanka defaulted. Colombo remains under Sri Lankan control but faces increasing Chinese pressure. A counter-offer—a charter port on better terms, with genuine technology transfer and capacity building rather than debt traps—could give Sri Lanka an alternative to Chinese dependency.

The Arctic Opening

Climate is opening shipping routes which were impassable for all of recorded history. The Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast is already navigable in summer. The Northwest Passage through the Canadian Arctic is following. As the ice retreats, new chokepoints are emerging, and whoever controls them will command a significant share of future global trade.

Greenland is the most tantalising possibility. It is nominally part of Denmark but exercises substantial autonomy. Its population is tiny, its resources vast, its strategic position commanding. A port on Greenland's west coast could serve as a hub for Northwest Passage traffic, for Arctic resource extraction, and for surveillance of North Atlantic sea lanes. The Danish government has resisted American attempts to purchase the island, but a more subtle approach—a charter arrangement which developed infrastructure without transferring sovereignty—might be acceptable.

Northern Canada offers similar opportunities, though Canadian sovereignty concerns would make any arrangement politically delicate. The Northwest Passage passes through waters that Canada claims as internal but that other nations regard as an international strait. A charter port on Canadian territory, developed with Canadian consent and subject to Canadian oversight, could resolve the sovereignty question while providing the infrastructure that Arctic shipping will eventually require.

Making An Offer No-One Can Refuse

But why would any country agree to this? Why would a sovereign state lease territory to a foreign power, even under contract, even with guarantees?

The answer is a well-designed charter city makes the host country strictly better off without taking anything away that it currently possesses.

Annual lease payments, indexed to inflation, providing guaranteed revenue regardless of global commodity prices. Throughput royalties on every container, every tonne of cargo, every megawatt of power, every gigabyte of data that passes through the zone. An equity stake in the operating company, transforming the port into a national asset that pays dividends rather than demanding subsidies.

The economic structure might look something like this:

- Base lease rent: A fixed annual payment, guaranteed regardless of the city's commercial success or failure. This provides the host government with predictable revenue that can be budgeted and borrowed against.

- Throughput royalty: Additional payments tied to actual use—perhaps $5 per container, $1 per tonne of bulk cargo, $0.10 per megawatt-hour of electricity consumed, $0.001 per gigabyte of data transited. As the city grows, the host's revenue grows with it.

- Sovereign equity stake: The host government receives shares in the City Operating Company—perhaps 15 to 25 percent—entitling it to dividends and board representation. This makes the host a partner rather than merely a landlord.

- Infrastructure escrow: A fixed percentage of the operating company's revenue is deposited annually into a ring-fenced fund that can only be spent on infrastructure within the host country. This ensures benefits flow beyond the port zone itself.

Beyond the direct payments, the infrastructure itself becomes a gift. Roads connecting the city to the interior, built by the operator but owned by the host. Power plants generating surplus electricity feeding the national grid. Desalination facilities providing fresh water to nearby towns. Fibre-optic cables landing on the coast and branching inland, bringing connectivity which would otherwise take decades to arrive.

Then there are the jobs.

Not just stevedores and clerks, but the entire ecosystem of a modern port city: logistics managers, maritime lawyers, insurance underwriters, ship chandlers, crane operators, data centre technicians. Training programmes that build local capacity. Scholarships which send promising students to universities across the network. Procurement requirements which favour local suppliers wherever feasible.

The host country does not surrender sovereignty. It leases a specific zone for a specific period—fifty years, seventy-five years, a century—with clear reversion clauses at the end. Inside the zone, commercial law operates autonomously; outside the zone, the host's law applies in full. Immigration controls ensure the port does not become a backdoor into the country. Workers enter on permits, work within the zone, and leave through the same gates they entered.

The political risk is managed through structure. Joint oversight boards with seats for both parties. Independent arbitration for disputes. Transparent accounting. Anti-corruption standards enforced by international audit. The city's legitimacy depends on its reputation, and its reputation depends on being boringly competent.

The Immigration Architecture & Free Movement

The question of movement is delicate. Any arrangement that allows foreigners to live and work on national territory raises concerns about demographic change, cultural impact, and security. These concerns must be addressed structurally, not dismissed.

Inside the zone, entry would be by permit only. Employers sponsor workers; workers receive permits tied to specific jobs; permits expire when employment ends. Biometric registration, background checks, and security screening would apply to everyone entering the zone. This is not open borders; it is managed access, similar to what exists in any international airport's transit area.

The zone would maintain strict exit controls into the host country proper. Workers are authorised to be in the zone, not in the country. Crossing from the zone into national territory would require the same documentation and approval as any other border crossing. The zone is a place of work, not a gateway.

Movement within the network, however, could be considerably freer. A worker with a valid permit at the Singapore node could be pre-cleared for employment at the Ghana node, with minimal additional paperwork. The network would maintain shared databases, shared security standards, shared credential recognition. This is the network effect applied to labour mobility: being inside the system confers advantages non-members do not enjoy.

For high-skill workers, longer-term residence within the network might eventually become possible. Something resembling the old British subject status—not citizenship, but a recognised legal status which confers rights across the network. This would not be citizenship of any particular state. It would be membership in an economic community, with rights and obligations defined by the community's charter rather than by any national law.

Power Without The Need For Conquest

For Britain, the benefits compound across the network. Each city is useful in itself, but the network is worth more than the sum of its parts. Common legal standards mean a contract signed in Dakhla is enforceable in Singapore, a ship registered in Guyana can dock in Colombo without additional paperwork, an arbitration award issued in one node is recognised in all the others. This is jurisdictional gravity: the tendency for disputes, financing, and commerce to route through systems which offer predictability.

The mechanisms of influence are subtle but substantial.

- Legal routing may be the most important. If a hundred nodes share a common commercial code—something like the old lex mercatoria, the law merchant that governed medieval trade fairs—then disputes, financings, and transactions will naturally route through that system. Lawyers will train in that system. Judges will build expertise in that system. Precedents will accumulate. The network becomes self-reinforcing because departing from it means accepting unfamiliar rules, unknown precedents, and unpredictable outcomes.

- Financial routing follows legal routing. Banks prefer to lend against assets protected by predictable law. Insurers prefer to underwrite risks in jurisdictions where courts are reliable. Capital flows toward certainty and away from arbitrariness. A network of charter ports, each offering the same legal guarantees, would attract capital away from jurisdictions that offer less.

- Maritime insurance once made London the indispensable centre of global shipping. Lloyd's of London underwrote the cargoes, Coutts extended the credit, and the courts of Chancery adjudicated the disputes. This infrastructure remains largely intact. A network of ports operating under London's legal umbrella would naturally draw marine insurance back to London, along with the brokerage, reinsurance, and litigation that marine insurance generates.

- Standards and certification are the invisible infrastructure of global trade. Goods must meet specifications; ships must meet safety requirements; ports must meet security protocols. Whoever sets the standards shapes commerce. A network which converges on common standards becomes a bloc that the rest of the world must accommodate. Products designed for network markets will dominate global trade simply because the network is large enough to justify dedicated production runs.

The strategic dimension is subtler but no less significant. A network of ports is also a network of anchorages, refuelling stations, and logistics hubs. Not bases in the imperial sense, bristling with guns and provoking nationalist resentment, but facilities available under treaty for specific purposes.

This is not about projecting military force for its own sake. It is about protecting the global commons—the shipping lanes, the cables, the airspace—on which everyone's prosperity depends. A British naval vessel conducting anti-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Guinea is not threatening anyone; it is providing a service which benefits every country whose trade passes through those waters.

The specific functions might include:

- Maritime security: Patrol of shipping lanes, interdiction of piracy, escort of vulnerable vessels through high-risk waters.

- Search and rescue: Coordination of emergency response across vast ocean areas, something that currently falls to whichever coast guard has the nearest vessel.

- Cable protection: The undersea cables which carry 99 percent of intercontinental data traffic are vulnerable to both accidental damage and deliberate sabotage. Protecting them is a global public good.

- Disaster response: Prepositioning of humanitarian supplies, rapid deployment of emergency personnel, coordination of relief efforts across regions.

None of this requires garrison troops or permanent military occupation. It requires access agreements, refuelling rights, and the legal framework to operate in someone else's waters with their consent. The ports provide that framework.

The Hardest Possible Test: Western Sahara

To see how this might work in practice, consider one of the worst cases imaginable: a charter port on the coast of Western Sahara.

The territory is contested, arid, sparsely populated, and almost entirely lacking in infrastructure. Morocco claims it and administers it; the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic claims it and contests Moroccan control; Algeria backs the Sahrawi cause; the United Nations has tried and failed for decades to organise a referendum on sovereignty. It is exactly the sort of place that sensible investors avoid.

And yet it is also Atlantic-facing, positioned between Europe, Africa, and South America, and close to sea lanes that will only grow more important as African economies develop. The coastline near Dakhla includes one of the finest natural harbours in West Africa. The offshore waters teem with fish. The desert interior offers almost unlimited potential for solar power generation. If a charter port can work there, it can work anywhere.

The first requirement is legal clarity. The agreement must be explicitly status-neutral, conferring no recognition or denial of any sovereignty claim. The port operates regardless of who ultimately governs the territory, because the port's legitimacy comes from commerce, not from taking sides in political disputes. The relevant clause might read:

This agreement confers no recognition, denial, or alteration of sovereign claims. The parties' positions on sovereignty remain entirely reserved.

This formulation is borrowed from how commercial actors have operated in other disputed territories. Oil companies operate in contested waters by signing agreements with all claimants simultaneously, or by structuring concessions so that revenues can be distributed regardless of which claimant prevails. Construction firms build infrastructure in places where borders are unclear by treating their contracts as commercial arrangements rather than political statements.

The offer to whoever administers the territory—currently Morocco—would be transformative.

A deep-water container port capable of handling the largest vessels afloat. The existing port at Dakhla is small and shallow, suitable only for fishing vessels and coastal traffic. A proper container terminal, with modern cranes, adequate storage, and efficient customs processing, would transform Dakhla into a regional hub.

A road corridor inland, connecting the coast to population centres that have never been connected to anything. Western Sahara's interior is almost roadless; the territory is administered from coastal towns with minimal penetration beyond. A paved highway connecting Dakhla to the Mauritanian border, or even to the Moroccan interior, would open new possibilities for trade, agriculture, and settlement.

Power generation—solar, certainly, given the Sahara's almost unlimited sunshine, perhaps supplemented by small modular nuclear reactors for baseload reliability—producing far more electricity than the port itself requires, with the surplus feeding towns and villages across the interior. Western Sahara currently has almost no electrical infrastructure outside the main towns. Rural electrification would transform daily life.

Submarine cable landings linking the territory to global communications networks. The West African coast is relatively underserved by intercontinental cables; a new landing station at Dakhla could branch to Europe, to the Americas, and to the rest of Africa. Along with the cable landing would come data centres—because once you have power and connectivity, data centres follow naturally, and data centres bring high-skill jobs and reliable revenue.

A hospital, staffed by international professionals but training local physicians and nurses. A technical college, teaching logistics, marine engineering, electrical installation, and all the other skills that a port city requires. Desalination plants, because fresh water is scarce in the Sahara and any significant development will require supplies beyond what wells and rainfall can provide.

All of this arrives without the host surrendering anything it currently possesses.

There is no tax base to lose, because there is currently almost no economic activity to tax. There are no sovereignty claims compromised, because the agreement is structured to be neutral. There is no demographic threat, because workers enter through controlled gates and do not have automatic rights to settle outside the zone.

What emerges is a city where none existed before, generating wealth that benefits both the operator and the host, connected to a global network which amplifies its significance far beyond its size. The desert becomes irrelevant. Only the coast matters, and the coast is transformed.

A British city.

Success Or Failure: Legitimacy

Everything described so far can fail in a single way: loss of legitimacy. If the ports become havens for illicit finance, they will be sanctioned and isolated. If labour abuses emerge, they will provoke outrage and political backlash. If the host population perceives the arrangement as exploitative, no contract will survive the next change of government. If great powers perceive a threat, they will apply pressure that no commercial entity can withstand.

The design must therefore be self-limiting. Maximum economic openness, minimum political footprint, airtight compliance with international standards. The ports must be boring. They must be governed by boring English administrators who care about container throughput and court backlogs, not by visionaries with grand ambitions. They must be so obviously beneficial to everyone involved opposition becomes politically costly.

This is the opposite of how empires usually behave. Empires overreach. They accumulate. They expand until they collapse. The thin empire, by contrast, succeeds by knowing what not to do. It provides the platform and collects the rent. It does not try to change cultures or install ideologies or reshape societies. It offers a service, and if the service is good enough, customers will come.

The specific safeguards would need to include:

- Anti-money laundering compliance: Full implementation of Financial Action Task Force standards, with independent auditing and real enforcement. The ports cannot become bolt-holes for oligarchs and drug lords.

- Beneficial ownership transparency: Public registries showing who actually owns companies registered in the zone. No more anonymous shell corporations.

- Labour standards: Wages, maximum hours, workplace safety requirements, and mechanisms for workers to file complaints without retaliation. Exploitation of workers would destroy the network's reputation within a decade.

- Environmental standards: Pollution controls, and genuine efforts at beneficial contribution. The era when colonial outposts could dump waste in harbours is over.

- Political neutrality: No support for any political party, no propaganda, no attempts to influence the host country's internal affairs. The ports are commercial facilities, not bases for ideological projection.

Only The British Could Do it

Britain is uniquely positioned to attempt this because of what it left behind. The common law is already the dominant legal framework for international commerce. Approximately 30 percent of the world's legal systems are based on English common law, and the proportion is higher for systems governing international trade. English is already the language of shipping, aviation, and finance. Maritime contracts are written in English. Air traffic control is conducted in English. The City of London remains one of the three dominant financial centres on earth.

British institutions—the City of London, Lloyd's, the Commercial Court, the London Metal Exchange—already handle disputes and underwrite risks which span the globe. The infrastructure is not physical but legal and procedural, and it is already in place.

More than that, Britain has done this before.

Not perfectly, but it built port cities which worked. Singapore, Hong Kong, and their peers did not succeed by accident. They succeeded because Britain learned, through trial and error over centuries, how to construct the conditions under which commerce flourishes.

That knowledge did not disappear when the empire ended. It remains encoded in institutions, in legal precedents, in the training of lawyers and bankers and maritime insurers, in the accumulated expertise of a small island that once managed the trade of half the world. The question is whether that inheritance can be put to new use, adapted for a century in which empire is unacceptable but commercial platforms remain as valuable as ever.

A Hundred Points of Light

Picture the world in fifty years, with a hundred nodes scattered across the map. Not red colonies but blue ports, each one a dot of prosperity in its region, each one connected to the others by law and logistics and mutual advantage.

Goods flow through them, and wealth accumulates. Disputes are settled in courts that traders trust. Ships refuel and refit and continue on their journeys. Cables land on their shores and branch into continents that were once disconnected. Power stations hum. Technical colleges train engineers who will build the next generation of infrastructure. The host countries grow richer, and Britain grows influential, and the world grows more connected.

None of this requires conquest. What it requires is competence, patience, and the recognition control of circulation matters more than control of territory.

The elephant is impressive, but the spider survives. The muscle is powerful, but the nerve controls the muscle. The empire of mass is obsolete. The empire of chokepoints endures.

Britain once knew this. Perhaps it is time to remember.