A Direct Liquid Democracy With MPs As Factors

You already live in a direct democracy because the Internet established it. You just haven't been told. Every hour, millions render verdicts no MP can hear on social media. The machinery of consent has outpaced the machinery of power. What remains is a choice: formalise it, or watch it rot.

Open your phone. Look at the last three things you liked, shared, or argued about. You just participated in governance. Not metaphorically. Not "in a sense." You rendered judgement on matters of public concern, added your weight to a position, and influenced—however fractionally—the behaviour of institutions, corporations, and other citizens.

This happens billions of times daily. It happens faster than any parliament can meet, any minister can respond, any civil servant can draft a memo. It happens so constantly we have stopped noticing it is happening at all.

We call it "social media." We call it "engagement." We call it "the discourse."

It is direct democracy. It arrived without permission, without referendum, without constitutional settlement. And it has already rendered representative democracy obsolete.

The question before us is not whether to adopt direct democracy. The question is whether to govern the direct democracy we already have—or continue pretending the old system still functions while legitimacy bleeds out of every institution we possess.

The Lie We Maintain

Here is the story we tell ourselves: every five years, citizens choose representatives. Those representatives go to Westminster, access information unavailable to ordinary people, debate amongst themselves, and render wise judgement on our behalf. We hold them accountable at the next election. The system works.

Every element of this story is now false.

Representatives do not possess information unavailable to citizens. The same leaked documents hit Twitter before they reach the Commons. The same academic papers are open-access. The same expert commentary is a podcast away. The knowledge asymmetry justifying delegation has collapsed entirely.

Representatives do not debate and render judgement. They follow whips, recite talking points, and calculate which faction to appease. The Commons is theatre. Decisions happen elsewhere—in cabinet, in committee, in conversations with donors and media proprietors—and the chamber exists to ratify them with a veneer of legitimacy.

Citizens do not hold representatives accountable. Incumbency advantages, safe seats, and party machinery ensure most MPs face no meaningful electoral threat. The median MP could vote against constituency interests for an entire parliament and face no consequence beyond an angry letter to the local newspaper nobody reads.

We maintain this fiction because the alternative terrifies us. If representation does not work, what does? If consent cannot be manufactured every five years and then ignored, how do we govern at all?

The answer is already here. We are simply refusing to look at it.

The Logistics Problem We Solved Two Centuries Late

Strip away the mythology and representative democracy is a workaround for a logistics problem: you cannot fit millions of people into a room.

In 1780, this was unsolvable. Gathering public opinion on any question took months. Letters went by horse. News travelled by word of mouth and printing press. By the time you knew what the public thought about a tax, the war it funded might already be over.

So we built a shortcut. Choose local delegates. Send them to London. Let them decide, then judge them later. Technically inferior to actual consent, but the best available given the constraints.

The constraints have evaporated. The workaround remains.

Direct democracy simply means removing the workaround. Instead of choosing someone to decide on your behalf, you decide yourself. Should we build this railway? You vote. Should we leave this treaty? You vote. Should we raise this tax? You vote.

This is not chaos. Switzerland has done it for over a century—citizens voting several times yearly on everything from immigration policy to tunnel construction. The Swiss are not rioting in the streets. Their government is not paralysed. If anything, Swiss policy is more stable, more legitimate, and more trusted than British policy has been in living memory.

But Swiss direct democracy was designed for paper ballots and slow deliberation. What technology now permits is something the Swiss founders never imagined: consent continuous, instant, and scalable to any population.

Liquid Democracy Solves the Attention Problem

Pure direct democracy has an obvious failure mode: nobody has time to vote on everything. Do you possess an informed opinion on agricultural subsidy reform? Fisheries quotas? Telecommunications spectrum allocation? For most questions, most people would rather abstain than pretend to expertise they lack.

Abstention at scale produces its own pathology: decisions made by the obsessive few, presenting as popular mandates.

Liquid democracy, as theorised by Lewis Carroll, resolves this with a single mechanism: revocable delegation.

You can vote directly on anything you care about. But for issues where you lack knowledge or interest, you delegate your vote to someone you trust—a friend who farms, an economist whose analysis you follow, a public figure whose judgement you have tracked over years.

That person now casts your vote alongside their own.

The crucial difference from representation: revocation is instant. The moment your delegate votes foolishly, you withdraw—and either vote yourself or delegate elsewhere. No waiting five years. No pretence of mandate. No "but I voted for you on other grounds."

Delegation can be topic-specific. Trust one person on economics, another on environment, a third on defence. Trust nobody on civil liberties and vote those yourself. The system accommodates any configuration of direct participation and selective delegation.

What emerges is a market in judgement. Delegates who prove wise accumulate influence; those who prove foolish lose it. Authority becomes earned rather than inherited, temporary rather than permanent, specific rather than general.

This is representation freed from its fatal defect: the fiction that a single vote every five years conveys meaningful consent to thousands of subsequent decisions. Under liquid democracy, consent is continuous. Trust flows upward only while earned. The public can redirect at any moment, on any issue, for any reason.

The Factor: An Older Form of Representation

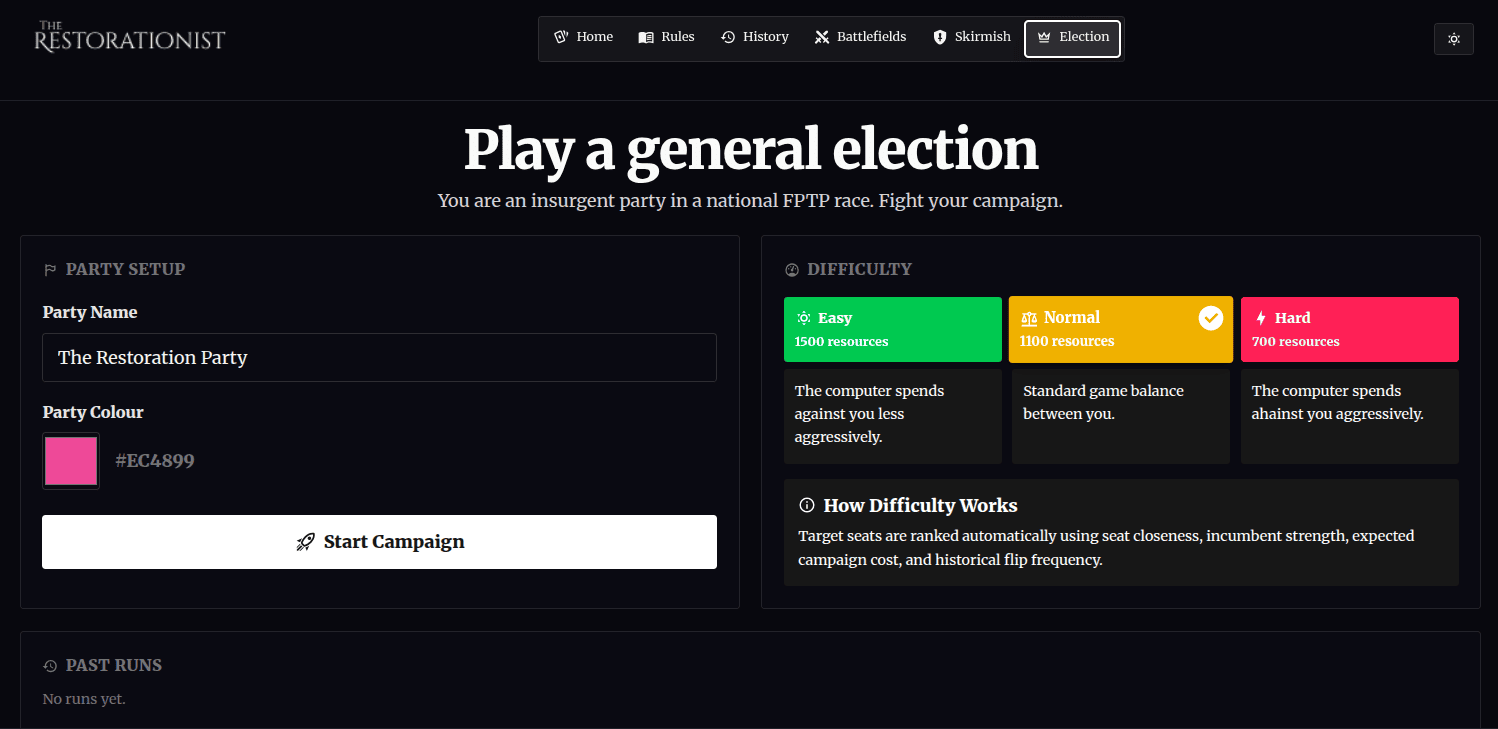

If representatives no longer interpret public opinion—if they execute instructions derived from continuous consent—what do they become? What is an MP in a world where the public votes directly?

The answer lies in history, not futurism.

Before mass democracy, before universal suffrage, before "representation" as we understand it, Britain operated a different model of delegated authority. The factor.

The definition, according to LexusNexus:

A factor is a mercantile agent who in the ordinary course of business is entrusted with possession of goods or of the documents of title to the goods1, and a broker is a mercantile agent who in the ordinary course of business is employed to make contracts for the purchase or sale.

In the trading posts of empire—East India Company warehouses, Caribbean sugar stations, African coastal forts—a factor was the man on the ground. He did not own the enterprise. He was not sovereign. He was an agent: entrusted with capital he did not own, empowered to act where communication was slow, constrained by standing instructions from London, judged on fidelity when accounts were audited.

In William Shakespeare’s Cymbeline, the wily Iachimo describes himself as such to Princess Imogen:

Some dozen Romans of us and your lord—

The best feather of our wing—have mingled sums

To buy a present for the emperor

Which I, the factor for the rest, have done

In France: ’tis plate of rare device, and jewels

Of rich and exquisite form; their values great;

And I am something curious, being strange,

To have them in safe stowage: may it please you

To take them in protection?

Crucially, factors exercised discretion. When pirates appeared or local wars disrupted trade, they made decisions no letter from London could authorise. They acted first and explained later.

But they answered for those decisions. Exceeding remit without cause brought dismissal, lawsuit, or prosecution. Wise emergency action brought reward. Authority was conditional on accountability. Trust was temporary, reviewable, subject to the opening of the books.

This is precisely the model liquid democracy requires.

The MP of the future is not a philosopher-king deliberating according to elevated conscience. Neither is he a puppet executing poll results. He is a factor: entrusted to act within standing instructions, empowered to deviate when genuine emergency requires, answerable when the books are opened.

Parliament does not vanish. It becomes the place where factors report, where overrides are scrutinised, where the boundary between instruction and discretion is adjudicated. It shrinks—dramatically—in size and spectacle. It grows in seriousness. MPs stop performing and start accounting.

This is restoration, not revolution. From Magna Carta's insistence authority exists within declared bounds, to the medieval borough's expectation delegates report back with accounts rendered, to Burke's assumption representatives answer for judgement—British governance has always rested on conditional authority and retrospective accountability.

Mass representative democracy broke this. It created permanent delegates, accountable only at distant intervals, interpreting mandates as they pleased, insulated by party machinery and safe seats.

Liquid democracy repairs it. Technology permits what the British constitution always assumed but never operationalised: continuous, visible, revocable consent.

When Opinion Becomes Constitutional Instruction

The objection writes itself: if public opinion merely advises Parliament, this is expensive market research. Another focus group for politicians to ignore.

So opinion must sometimes bind. The question is when—and the answer is time.

Not instantly. Not on a whim. Not because a hashtag trended for three days. Transient sentiment is not settled conviction, and only settled conviction should constrain the factor's discretion.

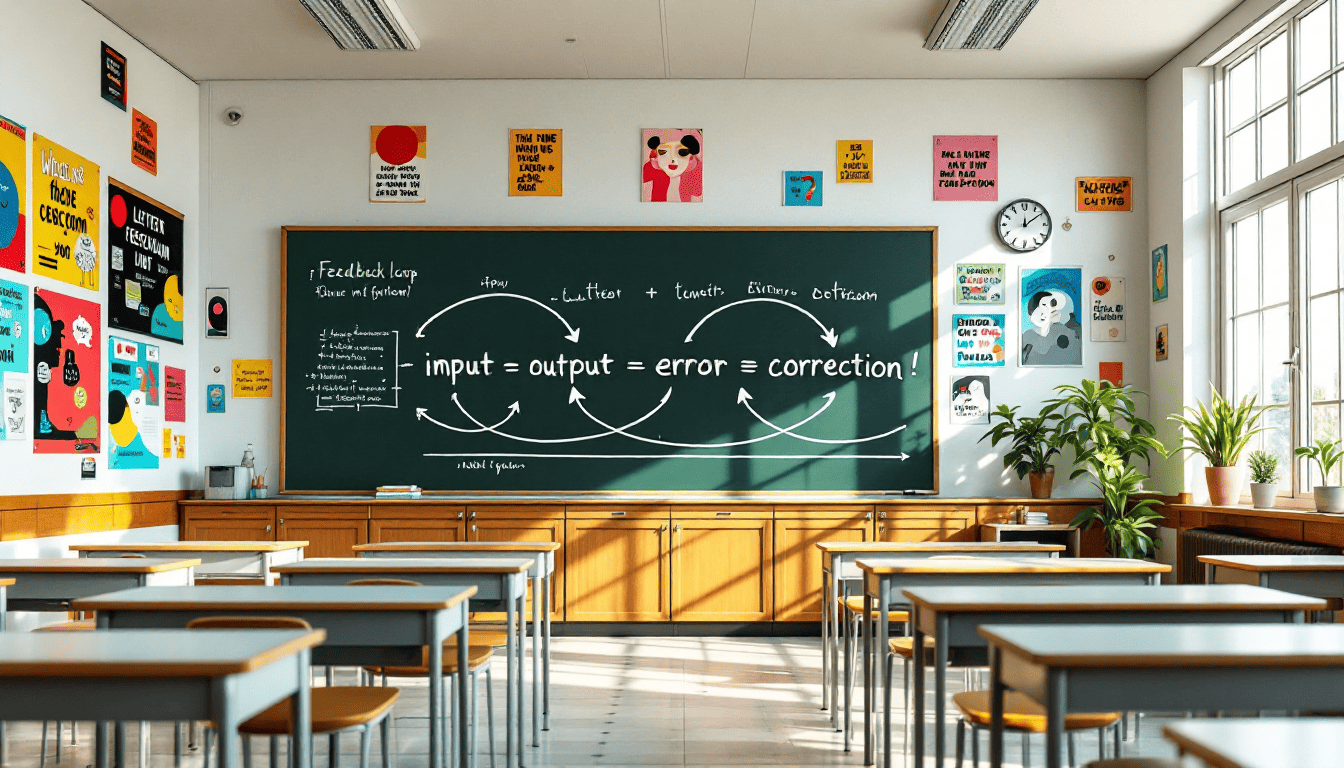

The system requires temporal filtering with explicit constitutional thresholds.

- Signals are instantaneous, non-binding, and informational. The public registers support or opposition; the registration is visible in real time. Politicians see it, journalists see it, everyone sees it—but it carries no legal force. This is weather: useful to observe, dangerous to obey.

- Sustained majorities trigger procedural obligations. When a clear majority—fifty-five per cent or above—persists on a question for six months with stable participation rates, Parliament cannot ignore it. It must bring forward legislation or publish formal justification for refusal. Silence becomes unconstitutional.

- Settled consent terminates discretion entirely. When a supermajority—sixty per cent—holds for twelve months or more on structural or constitutional questions, Parliament must implement. The public has spoken with such duration and consistency that continued resistance forfeits legitimacy.

The filtering mechanism matters. A sudden three-week panic looks nothing like a two-year conviction. Event-driven spikes are visible as spikes. Only positions held through multiple news cycles, through counterargument and counter-mobilisation, through the natural churn of attention—only these cross the threshold into binding instruction.

This is measured mechanically, not interpretively. The system tracks:

- Duration: how long has a majority held?

- Stability: how often has sentiment reversed?

- Participation consistency: are the same citizens engaged, or is turnout volatile?

- Intensity distribution: how strongly do supporters and opponents feel?

These metrics are public. Anyone can verify them. No politician can claim a mandate where the data show volatility, and no politician can dismiss opinion where the data show persistence.

Parliament retains judgement on volatile questions. But where the public demonstrates sustained, informed, persistent consent, the fiction of the representative mandate evaporates. Parliament becomes the instrument of expressed will, not its interpreter.

Eligibility Without Identity: The Cryptographic Settlement

The British public will not accept a national digital identity card. They are right to refuse. Central citizen registration becomes a lever of control, a surveillance apparatus, an instrument of abuse.

This system requires none of it.

The constitutional requirement is eligibility verification without identity disclosure. The existing electoral roll—held locally by councils, not centrally by Whitehall—already establishes who may vote. This does not change. What changes is how eligibility translates into participation.

The mechanism relies on anonymous credentials and zero-knowledge proofs.

When a vote opens, each eligible voter receives a single-use credential: a cryptographic token proving entitlement to vote on this specific question without revealing identity. Technically, this is implemented via blind signatures—the issuing authority signs a credential without seeing its content, preventing any link between issuance and later use.

When casting a ballot, you present a zero-knowledge proof demonstrating three claims:

- You possess a valid credential issued by an authorised local electoral office.

- The credential has not been spent on this vote before.

- Your ballot is well-formed (encodes a valid choice).

The system verifies all three claims without learning who you are, which office issued your credential, or how you voted.

Zero-knowledge proofs are not speculative technology. They are deployed at scale in cryptocurrency systems, identity verification platforms, and secure communications. The mathematics are settled. What remains is implementation—non-trivial, but engineering rather than research.

The critical properties:

- Unlinkability: the credential cannot be traced to the person who received it.

- Single-use enforcement: double-voting is cryptographically impossible, not merely detectable.

- Receipt-freeness: you cannot prove to anyone else how you voted, eliminating vote-buying and coercion verification.

The state never learns how you voted. A properly implemented system cannot even determine whether you voted. The guarantee is mathematical, not policy.

Device Loss, Key Compromise, and Recovery

Cryptographic systems fail when they ignore human reality. A phone is stolen. A key is lost. A password is forgotten. If the system cannot handle these cases gracefully, it is worthless.

The design separates three functions usually conflated:

- Eligibility: are you entitled to vote?

- Authentication: is the person casting this ballot actually you?

- Secrecy: can anyone learn how you voted?

Your phone holds a cryptographic key, protected by PIN or biometric unlock. This key is stored in the device's secure enclave (hardware-backed on modern smartphones) and never leaves in readable form. A thief cannot extract it.

But the phone is not your identity. You hold a separate recovery credential—a paper backup, a hardware token, codes stored with a solicitor—maintained offline and used only for recovery.

If your phone is stolen:

- You authenticate using the recovery credential.

- The system revokes the stolen device's key.

- You bind a new device key.

- Unused voting credentials linked to the stolen key are invalidated.

The attacker now holds a device containing a revoked key—useless.

If someone steals your phone and votes before you notice, two safeguards apply:

- Re-voting windows: only your final vote within the voting period counts. If an attacker casts a ballot, you recover access and re-vote, overriding the fraudulent submission. This also addresses coercion—if someone forces you to vote a certain way, you can comply, then privately re-vote later.

- Multi-factor authentication for high-stakes votes: general elections or constitutional referenda can require confirmation from both device key and recovery credential, making the stolen phone alone insufficient.

If you lose both phone and recovery credentials, you attend your local electoral office in person—exactly as you would today for a registration error. Eligibility is re-verified through existing offline processes. A new recovery credential is issued. Prior credentials are invalidated.

The offline fallback is slow, deliberate, and boring. It requires no central biometric database, no digital identity infrastructure, no new surveillance capacity. It works because eligibility remains grounded in existing local electoral administration.

The MIT Objection Stands—For the Systems They Critiqued

Computer scientists have warned, repeatedly and forcefully, against internet voting. The objections are serious and deserve engagement rather than dismissal.

The core critique, articulated most sharply by MIT's Ron Rivest and others, focuses on three structural vulnerabilities in existing e-voting proposals:

- Secret software: proprietary voting machines run code the public cannot inspect. A hidden bug or backdoor alters results invisibly.

- Central tabulation: all votes flow through one counting system. Whoever controls it controls the election.

- High-stakes single events: a general election happens once. Compromise is irreversible.

These objections are correct. They remain correct.

But examine what they critique: closed, centralised, opaque, one-shot systems. The liquid democracy model differs on every axis.

- Open-source software: every line of code is published, reviewed by independent auditors, compiled by multiple parties, and verified against published specifications. Builds are reproducible—anyone can compile from source and confirm the binary matches what is deployed. Fraud requires compromising not one machine but a distributed network, and compromise is detectable by anyone with technical capacity to audit.

- Decentralised tabulation: local returning officers issue credentials. Tallies are computed via publicly verifiable cryptographic proofs—anyone can verify the sum is correct without accessing individual ballots. No single authority controls the count. Manipulation requires collusion across independent institutions and leaves cryptographic traces.

- Distributed stakes: continuous voting on many questions differs fundamentally from single high-stakes elections. Compromise of one vote is serious but recoverable—the next vote occurs within days or weeks. Attack incentives are reduced; detection opportunities are multiplied.

This does not produce perfect security. Perfect security does not exist. The design provides detectability: fraud becomes visible even when it cannot be entirely prevented.

That is the only standard British elections have ever met. No paper election in history has been immune to fraud. The question is whether fraud can be discovered and corrected. Open systems under continuous public scrutiny meet that standard far better than paper ballots in locked warehouses overseen by party appointees.

Issuance Control: Who Poses the Question

If anyone can launch a vote at any time, the system drowns in noise. An infinite stream of trivial polls makes meaningful consent impossible. Issuance must be controlled—but not by those whose power depends on limiting democratic participation.

Three tiers of public expression with distinct issuance rules are required.

Signals

Signals are (non-binding sentiment measurement) can be launched by:

- Individual MPs

- Select committees

- Local authorities

- Citizen petitions crossing a modest threshold (e.g., 25,000 eligible participants)

Each issuing body faces rate limits. Duplicate or near-duplicate questions trigger cooling-off periods. The output is public sentiment data—turnout, support levels, demographic distribution—with no legal force.

Parliamentary petitions

Petitions (procedural triggers) operate on escalating thresholds:

- 50,000 supporters → written ministerial response required

- 250,000 supporters → select committee hearing required

- 500,000 supporters → Commons debate required

- 1,000,000+ supporters → eligibility for referendum trigger review

Petition texts are fixed at submission. Material alterations require resubmission and threshold reset. Defeated petitions cannot be resubmitted unchanged for twelve months.

Referenda

Referendums (binding decisions) require high barriers:

- Parliamentary supermajority, or

- Statutory threshold of MPs (e.g., 15% of the Commons), or

- Citizen petition crossing a very high bar (e.g., 10% of the electorate)

Individual MPs acting alone cannot trigger referenda. Ministers cannot. Trending hashtags cannot. Constitutional seriousness demands constitutional process.

Spam control is mechanical. Rate limits, immutability requirements, cooling-off periods, and high thresholds for binding force filter transient enthusiasm. The system measures persistence, not volume.

The Emergency Override and Its Accountability

Every constitutional system must answer the hardest question: what happens when government possesses information the public does not, and acting on it requires overriding public opinion?

The Cabinet holds classified intelligence. A hostile power prepares a strike. Prevention requires military action the public opposes. Disclosure tips off the enemy and compromises sources. Delay costs lives. A public vote would be catastrophic.

No honest constitutional theory pretends this away. It is the limit case separating serious proposals from fantasy.

The answer is not pretending direct democracy replaces executive judgement under asymmetric information. The answer is constitutionalising the exception—making override visible, bounded, and accountable.

A narrow class of existential security actions is explicitly excluded from ordinary public voting by statute, not convention. Such actions proceed only with structured concurrence:

No single actor invokes emergency powers alone.

The critical innovation is temporal accountability. Emergency action overrides public sentiment temporarily—never permanently.

A clock begins at the moment of action. Within defined periods—thirty, sixty, ninety days—disclosure commences. Justifications are published. A sealed intelligence ledger, created at the time of action, records the claims and confidence levels on which the decision rested.

Eventually, structured review permits public verdict: not whether the decision was wise, but whether override was justified on information now available. The ledger is opened. Claims are compared against outcomes. Exaggeration is detectable. Abuse is punishable.

This restores the second half of Burke's model—the half modern representative democracy quietly abandoned. Burke never argued for unaccountable discretion. He assumed representatives would answer for judgement, Parliament would examine, and records would exist.

Today's executives act on secret intelligence, provide minimal explanation, and face no binding post-hoc mechanism. The factor model reverses this: overrides are logged, justifications are mandatory, review is automatic, authority is withdrawable.

The lie is not that leaders must sometimes act against opinion. The lie is pretending they can do so without eventual consent.

Administration Is Where This Matters Most

Direct democracy is typically debated as a rival to Parliament. This misses where it is most powerful and most disruptive: local administration.

Councils are not mini-parliaments exercising Burkean judgement. They are planning authorities, licensing bodies, service allocators, regulatory intermediaries. They exercise discretion over citizens' lives in domains where:

- Knowledge asymmetry is minimal (residents know their neighbourhoods)

- Stakes are concrete and reversible

- Decisions are frequent

- Opacity is maximal and capture is easiest

The excuses for representative insulation collapse entirely at this level.

The proposal is disaggregation. Split council functions:

- Market mechanisms for priced services. Competition, contracting, citizen choice expressed through purchasing rather than voting.

- Parish and community governance for human-scale decisions. Direct democratic participation works naturally where populations are small and stakes are local.

- Constrained rule-setting for regulatory functions. Digital consent operates as approval or veto power over specific rule changes, not as policy origination.

What vanishes is the monolithic council—simultaneously planner, moral arbiter, service provider, and political shield for decisions nobody voted for.

The most powerful application of voting here is not "what should we do?" but "may this be done?" Approval thresholds for planning changes. Sunset requirements for licensing rules. Veto triggers for regulatory overreach. These are constraints on discretion, not substitutes for expertise.

Digital voting excels at constraints.

Resurrecting The British Tradition

Britain is not inventing a new democratic form. It is recovering an older one. The oldest English constitutional instinct holds power as conditional, not absolute. Magna Carta did not create democracy. It did something subtler: bound authority to declared limits and made deviation reviewable. Emergency power was acknowledged—but accountable. Breach of conditions voided legitimacy.

Medieval governance operated through shires, boroughs, guilds, and parishes. These bodies did not "elect rulers." They authorised agents for specific purposes and expected accounts rendered. Delegates were messengers bound by instruction, not sovereigns exercising independent judgement.

Parliament itself began as consent-aggregator, not legislature. Its purpose was registering assent to taxation, hearing grievances, confirming standing instructions to the Crown. Legislation emerged later. The original function was clearing house for consent.

The Privy Council embodied discretionary emergency power. Some matters require secrecy and speed. But Councillors were trusted because they were accountable. Records were kept. Abuse could be punished afterwards.

The common law tradition embeds the same logic: discretion bounded by precedent, reviewed retrospectively. Judges act, then face appeal. Commanders act, then face court martial. Trustees act, then face suit. Authority first, accountability after—but accountability always.

Mass representative democracy disrupted this pattern. It created a class of permanent delegates, accountable only episodically, insulated by party and procedure, claiming mandates they cannot demonstrate for decisions they never submitted to consent.

What technology now permits is not innovation but restoration. Continuous consent. Conditional delegation. Retrospective accountability. Standing instructions modified by persistent public conviction.

The British constitution always assumed these. It simply lacked the means to operationalise them at scale. The means now exist.

Bringing What Is Self-Evident To Life

Direct liquid democracy does not ask representatives to obey opinion. It asks them to execute instruction—and justify deviation.

The representative becomes a factor: an agent of aggregated judgement, trusted to act where consent is slow, never permitted to forget where authority originates.

Parliament does not disappear when consent becomes continuous. It is clarified. It stops pretending elections confer permanent authority. It governs instead in dialogue with a public whose will is measured not by noise but by persistence.

Digital tools do not replace British constitutional tradition. They allow it to function again.

Britain does not need a new democracy. It needs its old instincts—conditional trust, bounded discretion, retrospective accountability—finally matched to modern capability.

The democracy is already here. It arrived without the permission of our little Maharajahs in Parliament. The only remaining question is whether we govern it—or let it govern us.