A Social Contract Enforced Without Consent

Why are we bound by obligations we never agreed to, funding priorities we cannot influence, under rules that cannot be reversed? Britain's social contract was supposed to bind both citizen and state. Now it binds only one. The bill has arrived, and an entire generation is refusing to sign.

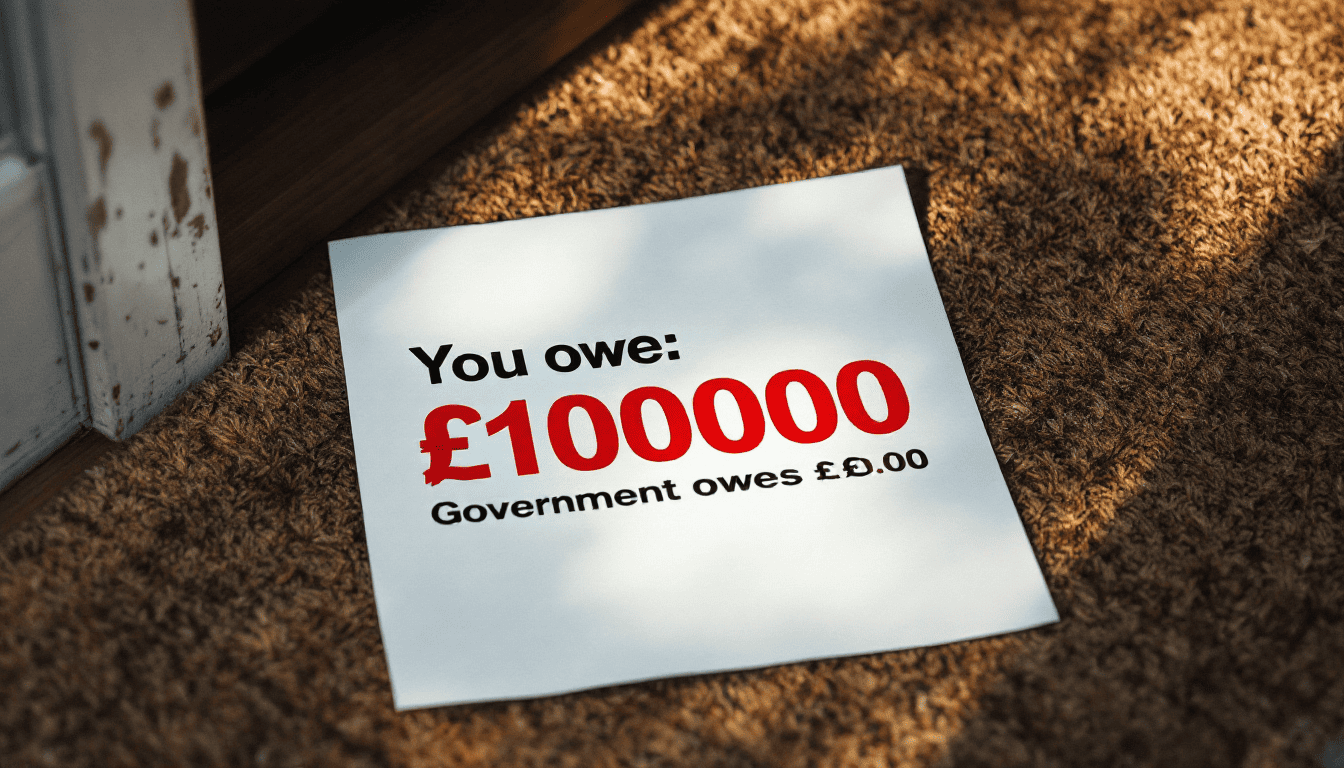

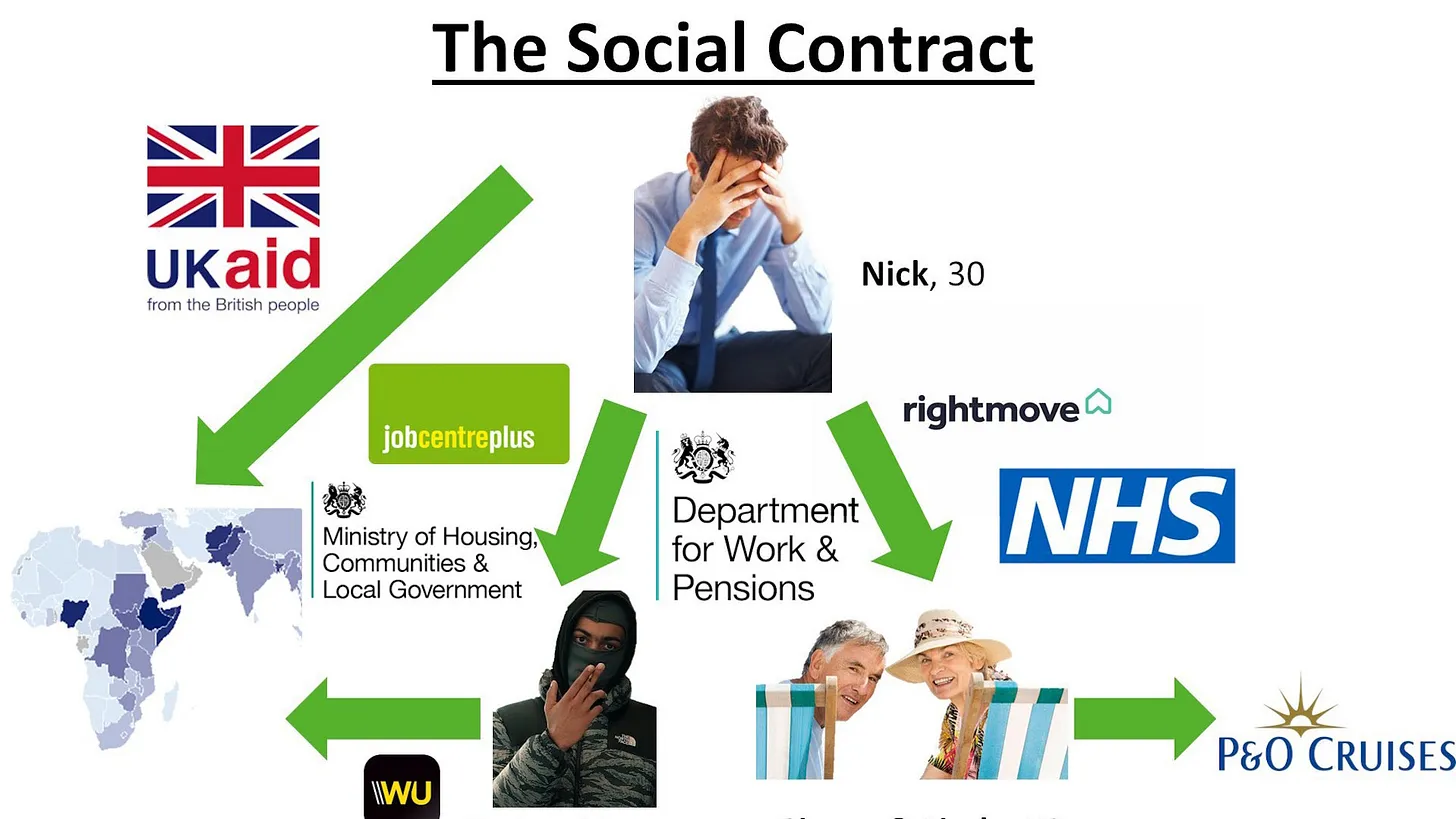

A thirty-year-old man looks at his payslip. He earns enough to be taxed substantially, but not enough to buy a house in the town where he grew up. He funds a pension system actuaries have told him will not exist when he reaches sixty-seven. He pays for a health service he cannot access without a three-week wait. He watches as people who arrived last month are housed in serviced apartments while he shares a flat with strangers. He is told, constantly, this is solidarity. This is fairness. This is the deal.

He does not remember signing any deal.

The French have a name for him: Nicolas, 30 ans. The meme spread across Europe because it named something millions of young people recognised but could not articulate—the sensation of being perpetually billed for goods never delivered, of funding a civilisation increasingly designed around someone else's priorities, of being told the arrangements are non-negotiable while watching those arrangements visibly fail.

It has even evolved in to a full online game you can play at https://nicksimulator.com/

Nick is not a radical. He is not even particularly angry, most days. He is exhausted. He works. He pays. He follows rules. And he has slowly come to understand something his parents' generation never had to confront: the system takes, but it no longer asks. The "social contract" everyone invokes has become a one-way extraction mechanism dressed in the language of mutual obligation.

This is not a failure of generosity. Britain remains, by historical standards and despite its GDP per capita, an astonishingly wealthy country. This is something more dangerous: a failure of consent. And when consent fails, legitimacy follows—quietly at first, then all at once.

The Phantom Agreement No One Defines

Politicians love the phrase "social contract." It sounds profound. It implies mutual obligation, shared sacrifice, the wisdom of ages. It shuts down arguments: we all agreed to this, and now you want to welch?

But when pressed, no one can tell you what it actually contains. No one can point to the moment it was agreed. No one can explain why it seems to expand obligations on citizens while shrinking guarantees from the state. The social contract, as deployed in modern British political discourse, is not an agreement at all. It is a rhetorical bludgeon—a way of declaring debate closed by invoking a consensus that was never reached.

A real contract has properties.

- It is bilateral: both parties owe something, and both parties can enforce their claims.

- It is specific: the terms are defined, not gestured at.

- It is temporal: consent given in 1945 does not bind citizens born in 1995 to arrangements they never approved. And crucially,

- It is revocable: a contract where one party can never exit is not a contract but a sentence.

By these standards, Britain's supposed social contract fails on every count.

The citizen's obligations are clear enough. Pay your taxes. Obey the law. Accept the decisions of those in authority. Do not make trouble. Fund whatever the state declares necessary. Absorb whatever demographic, economic, or constitutional transformation the political class considers desirable. Ask no awkward questions. Vote if you like, but understand the outcomes are largely predetermined.

The state's obligations, meanwhile, have become remarkably fluid. Protection? The police solve fewer than six percent of crimes. Justice? The courts have a backlog stretching years. Secure borders? The Channel crossing has become a scheduled service. Stable currency? Ask anyone who remembers what their savings could buy a decade ago. Predictable governance? Ask anyone who lived through 2022.

When obligations accumulate on one side while guarantees evaporate on the other, the contract is not evolving. It is dying. And the people bound by it have started to notice.

How English Liberty Became Admin Compliance

The idea government must justify itself is not some libertarian import from America. It is the oldest instinct in English public life, and it was forged in direct confrontation with overreaching power.

Magna Carta was not a declaration of abstract rights. It was something more subversive: a statement the king himself was bound. Taxation required consent. Liberty could not be arbitrarily removed. Law preceded the ruler rather than emanating from him. This was not democracy in the modern sense—the barons at Runnymede were not egalitarians—but it established a principle which would echo through eight centuries of constitutional development: power exists only within limits it did not create.

Parliament hardened this instinct into institutional form. Taxation tied to representation. Law made publicly, debated openly, and constrained retrospectively. Authority exercised through recognisable bodies which citizens could identify and, crucially, influence. The English system never assumed the people were sovereign in the abstract philosophical sense the French Revolution proclaimed. It assumed something more practical and more durable: power survives only so long as the public tolerates it.

The 1689 Bill of Rights made the bargain explicit. The Crown governs under conditions. Rights are not gifts from the state to be withdrawn at convenience. Government exists by continued acceptance, not by inherited right or administrative fiat. This is what distinguished England from the continental systems of absolute monarchy: authority was contingent, not sacred.

A. V. Dicey captured this settlement with forensic precision in the nineteenth century. For Dicey, the rule of law meant no person or institution stood above legal constraint, power required justification in statute, and discretion was a danger rather than a virtue. His constitution was procedural, not moral. It did not ask whether government was doing good things. It asked whether government was doing authorised things. The distinction is everything, and it has been almost completely reversed.

Modern Britain treats legitimacy as something settled generations ago, a box ticked and filed away. Parliament still sits, but increasingly defers to executive orders, statutory instruments, and administrative bodies no voter has heard of. Law still exists, but bends to "necessity" declared by ministers. Consent is assumed rather than sought, and when it is sought—as in 2016—the system spends years demonstrating it never really wanted an answer.

This is not constitutional continuity. This is constitutional drift, and the people living under it can feel the ground shifting beneath them even when they lack the vocabulary to describe it.

The Healthcare System State Religion

The British public liked the idea of a national health service. They still do. Universal healthcare, free at the point of use, funded by general taxation: the principle commands overwhelming support across every demographic and political persuasion. This is not in dispute.

What was never agreed—what was never even proposed for agreement—was the transformation of healthcare into the central moral fact around which all other policy must orbit. The NHS has become Britain's established church, its clergy beyond criticism, its congregation compelled to tithe regardless of the quality of service received.

The NHS now consumes roughly forty-four percent of day-to-day public spending. Its budget has grown in real terms almost every year for decades, yet waiting lists lengthen, outcomes lag behind comparable nations, and the system lurches from crisis to crisis with metronomic regularity. No other institution in British public life is permitted such consistent failure without consequence. No other institution commands such reflexive deference.

When the pandemic arrived, the country was not locked down to protect the public. It was locked down to "protect the NHS"—as though the health service were an end in itself rather than a means to an end, as though citizens existed to serve the institution rather than the reverse. Other countries managed to balance public health against liberty, economy, education. Britain chose the healthcare system as its supreme value and sacrificed everything else on its altar.

None of this was consented to. The 1945 generation agreed to healthcare provision. They did not agree to healthcare as state ideology. They did not agree to the entire political economy being restructured around a single institution's demands. They did not agree to their grandchildren paying ever-higher taxes for ever-declining access. A bargain this consequential deserves periodic renewal. It has never received one.

Factories Closed, Skills Dispersed, Sovereignty Surrendered

Britain in 1979 had problems. Militant unions, inefficient nationalised industries, an economy struggling to compete. Reasonable people disagreed about solutions, and the electorate voted for change.

What they voted for was adaptation. What they got was transformation—and no one asked whether the transformation was desirable before it became irreversible.

Deindustrialisation was not a natural process, some inevitable tide of history washing over helpless policymakers. It was a choice, and the choice was made without meaningful public debate. When the mines closed, the steelworks shuttered, the shipyards fell silent, the population affected was told this was "progress." The global economy demanded it. There was no alternative.

But there were alternatives. Germany maintained its industrial base. Japan protected strategic manufacturing. Even America, apostle of free markets, retained sovereign capacity in sectors it considered vital. Britain alone treated manufacturing as something to be discarded, industrial skills as relics of a bygone age, and strategic self-sufficiency as an embarrassing anachronism.

The consequences accumulated slowly, then arrived all at once.

- When the pandemic struck, Britain could not manufacture basic medical supplies.

- When energy prices spiked, Britain had no domestic production to cushion the blow.

- When supply chains fractured, Britain discovered it had outsourced capacity it could not easily rebuild.

The public never consented to this. They were told the choice was between modernisation and decline, between embracing globalisation and retreating into irrelevance. What they were not told—what they were never asked—was whether they wished to trade sovereignty for efficiency, resilience for short-term growth, national capability for quarterly returns.

Change sold as adaptation was actually abdication. And the bill is still being presented, decades later, to people who had no voice in the original transaction.

Common Market Became a Political Prison

The 1975 referendum asked whether Britain should remain in the European Economic Community. The question was about trade. The campaign was about trade. The leaflets, the broadcasts, the political arguments—all focused on a common market, customs arrangements, economic cooperation with continental neighbours.

No one asked whether Britain wished to become a political satellite of a supranational bureaucracy.

The evolution from trade bloc to political union happened incrementally, treaty by treaty, competence by competence. Each step was presented as technical, administrative, merely tidying up existing arrangements. The cumulative effect was the transfer of lawmaking power from Westminster to Brussels, the subordination of British courts to European judges, and the steady erosion of parliamentary sovereignty Dicey had identified as the cornerstone of the constitution.

When the public finally got a vote on the destination this journey had reached, they voted to leave. The response from the political class was three years of procedural sabotage, legal obstruction, and outright contempt for the expressed will of the electorate. Parliamentary manoeuvres designed to reverse the result. Courts claiming authority to second-guess the referendum. Media campaigns portraying Leave voters as dupes, racists, or senile pensioners whose preferences could safely be ignored.

This was the moment the mask slipped entirely. When consent was finally given clearly and unambiguously, the system revealed it no longer recognised the speaker. The social contract everyone had been invoking was exposed as purely rhetorical—a tool for extracting compliance, not a framework for mutual obligation.

Brexit itself is now a secondary matter. The constitutional revelation is what endures: when the public's answer differs from the approved answer, the public's answer becomes the problem to be managed rather than the mandate to be implemented.

State-Level Restraint Became Individual Litigation

Britain played a leading role in drafting the European Convention on Human Rights. The historical context was clear: after the horrors of totalitarianism, states needed external constraints. Never again would governments be able to hide behind sovereignty while brutalising their populations. The Convention was a shield against tyranny, and Britain was proud to help forge it.

What Britain did not consent to—what was never put to any democratic test—was Protocol 11 in 1998, which allowed individual petitions to proceed to Strasbourg regardless of domestic resolution. This transformed the system from a check on state abuse into a mechanism for transnational judges to override domestic law on questions of ordinary policy.

The result has been the progressive judicialization of politics. Questions which should be resolved by elected representatives—immigration policy, security measures, the balance between liberty and order—are instead determined by courts operating under treaties the public has no meaningful ability to influence. Democratic law has been subordinated to transnational process, and the process has no mechanism for popular input.

When Parliament passes legislation the courts dislike, the legislation is struck down or reinterpreted into meaninglessness. When the public votes for parties promising particular policies, those policies are blocked by legal challenges. The system designed to prevent governments from abusing their people has become a system preventing peoples from governing themselves.

Rights were meant to restrain power. They are now used to nullify it—specifically, to nullify the power of electorates to shape policy through their votes. This is not what anyone agreed to in 1950, and the fact the transformation happened through legal accretion rather than explicit amendment does not make it consensual.

Hospitality Transformed Into Demographic Revolution

Britain has always taken in refugees. This is a point of genuine national pride, and it should remain so. From Huguenots to Jews fleeing persecution, from Ugandan Asians to Vietnamese boat people, the country has a long tradition of offering sanctuary to those genuinely fleeing danger.

But sanctuary is not what current policy provides. What has been implemented, without any democratic mandate, is mass immigration as fiscal strategy—the use of population growth to paper over declining productivity, fund unsustainable pension commitments, and avoid difficult decisions about economic reform.

Net migration to the United Kingdom exceeded 700,000 in recent years. This is not a refugee programme.

Countries do not generate seven hundred thousand refugees annually.

This is demographic transformation by administrative decision, and the transformation has profound implications for housing, infrastructure, public services, wages, and social cohesion—none of which have been honestly debated, let alone approved. It is, however, politically comfortable for parties to whom immigrants can be convinced to sign their ballot for.

The British public has expressed clear preferences on immigration in every available forum. They have voted for parties promising reduction. They have told biased pollsters they want lower numbers who are forced to doctor their feedback. They have demonstrated, when given the opportunity, their dissatisfaction with the status quo.

The response from the political class has been to ignore these preferences entirely while lecturing citizens about their moral obligations to accept whatever numbers the Treasury and Home Office consider convenient. Compassion has become compulsion. Hospitality has become policy imposed without consent.

This is not a debate about whether immigration is good or bad in the abstract. It is a question of who decides, and on what basis. A transformation this consequential—affecting housing, schools, hospitals, wages, communities, and the very composition of the population—requires explicit democratic endorsement. It has never received one. And when people object to this, they are told their objections are themselves illegitimate.

House Arrest by Statutory Instrument

In March 2020, the British population was confined to their homes by ministerial decree. Set aside, for a moment, whether this was wise epidemiological policy. Set aside the arguments about lives saved or lost, economic damage incurred or avoided.

Consider only the constitutional question: by what authority was this done?

The answer is the Public Health Act 1984, which grants ministers power to make regulations for "preventing, detecting, controlling or providing a public health response to the incidence or spread of infection." The act was not written with house arrest in mind. It was not written to authorise the closure of businesses, the prohibition of worship, the banning of funerals. It was certainly not written to permit ministers to criminalise visiting elderly relatives or sitting alone on a park bench.

Parliament did not vote on the lockdown before it was imposed. The measures were introduced by statutory instrument—secondary legislation requiring no advance approval by elected representatives.

For weeks, the country lived under restrictions that had never been debated, never been subjected to scrutiny, never been exposed to the challenge and counter-argument that parliamentary procedure exists to provide.

This was unprecedented in the strict sense. No previous emergency—not the Blitz, not the Troubles, not any prior pandemic—had resulted in the entire population being confined to their homes by executive fiat. The ancient liberties which survived the Second World War, survived centuries of war and plague and political crisis, were suspended by ministers acting without meaningful parliamentary oversight.

The public had consented to caution. They had not consented to the abolition of normal constitutional procedure. They had not consented to criminalisation of ordinary life by regulations made behind closed doors. They had not consented to police forces interpreting ministerial guidance as though it were criminal statute.

And perhaps most damningly: they complied. Not because the measures were obviously lawful, but because resistance had been trained out of them over decades. The habit of deference, the assumption authority must have good reasons, the ingrained sense the state knows best—all of it meant the constitutional outrage barely registered. Emergency powers were normalised not because they were legitimate, but because the population had forgotten what legitimacy required.

The Quiet Catastrophe of Contractual Vacancy

Here is where Britain finds itself: not on the brink of revolution, not in the grip of mass unrest, but in something more corrosive—a state of contractual vacancy.

The social contract has not been dramatically torn up. It has been quietly hollowed out. The forms remain: elections, Parliament, laws, institutions. But the substance has drained away. The relationship between state and citizen is no longer one of mutual obligation. It is one of administrative management, where the population is processed rather than consulted.

Nick, 30 ans pays his taxes and receives declining services. He follows rules which change without notice and multiply without justification. He funds pensions he will never receive, houses he will never occupy, priorities he was never asked to endorse. He watches as every lever of supposed democratic influence produces the same outcomes regardless of which way it is pulled.

And so he does what people do when contracts break down: he withdraws. Not dramatically, not violently, not in ways that make headlines. He simply stops believing. He complies, but minimally. He participates, but cynically. He remains lawful, but disloyal.

This is the most dangerous political condition of all. Order without legitimacy is merely enforcement, and enforcement is expensive—not just financially, but socially. A state that governs by compliance rather than consent must constantly expand its apparatus of monitoring, regulation, and coercion. It must treat scepticism as pathology and dissent as disorder. It must replace persuasion with propaganda and argument with assertion.

Britain has been doing all of these things, for decades, without ever acknowledging the underlying problem: the people have stopped consenting, and the system has stopped asking.

When the Exit Signs Are Removed

Withdrawal of consent is not a single act. It is not inherently violent or even unlawful. For most people, most of the time, it looks like nothing at all: quiet disengagement, minimal cooperation, refusal to internalise official stories, preference for family and community over institutions that no longer serve.

Historically, rulers feared this form of withdrawal more than open rebellion. Mockery is more dangerous than protest. A population which laughs at authority has already decided it lacks legitimacy. A population which routes around the state rather than engaging with it has already seceded in spirit.

The memes are diagnostic. Nick, 30 ans is not a programme or a manifesto. He is a laugh—and the laugh means the game is up. When the young mock their rulers' earnest claims to moral authority, when they refuse to take seriously the institutions demanding their sacrifice, when they treat the entire performance of democratic legitimacy as an inside joke, something fundamental has shifted.

The English constitutional tradition understood consent must be renewable, grievances must have outlets, and the relationship between ruler and ruled must be periodically renegotiated. Remove the exit signs—make it clear no vote will ever produce change, no complaint will ever be heard, no transformation will ever be reversed—and something breaks. Perhaps not immediately. Perhaps not visibly. But irreparably.

This is not a demand to return to the past. The factories will not reopen, the (first) empire will not return, the world of 1955 is not available as an option. But that is not what the demand is about.

The demand is simpler and more radical: to be asked.

To have a genuine voice in the transformations that reshape our lives. To be treated as citizens rather than resources. To have our consent sought rather than assumed, our objections heard rather than pathologised, our votes counted rather than managed.

A society which stops asking should not be surprised when consent quietly evaporates. Britain stopped asking decades ago. The evaporation is well underway. And the people who created this situation are the last to see it, because they long ago stopped believing they needed permission.

The social contract we never signed is being returned to sender. Whether the state acknowledges the receipt is its own affair. The withdrawal is already happening, one disengaged citizen at a time, one mocking meme at a time, one shrug of indifference at a time.

Nick, 30 ans is not apathetic. He is post-consent. And he is not alone.