Chasing The Restless Ghost Of Kurt Cobain

For thirty years, two camps have shouted past each other over Kurt Cobain's death. Both are guessing. One chemical measurement could end the argument forever — and it has been sitting in a filing cabinet in Seattle since 1994. If it's not that smoking gun, it's time to let him rest in peace.

On the morning of 8 April 1994, an electrician named Gary Smith arrived at a large house in Seattle's Denny-Blaine neighbourhood to install a security system. He glanced through the French doors of a greenhouse above the garage and saw a body on the floor. A Remington Model 11 twenty-gauge shotgun lay across the dead man's chest. A note, written in red ink on a restaurant placemat, was impaled by a pen into the soil of a raised planter behind his head. The window below the door handle was intact; emergency responders would break it to gain entry. Three days of decomposition had already begun.

The King County Medical Examiner would rule the death a suicide. The dead man was Kurt Cobain. The world would never quite accept it — and the world would never quite be given sufficient reason to.

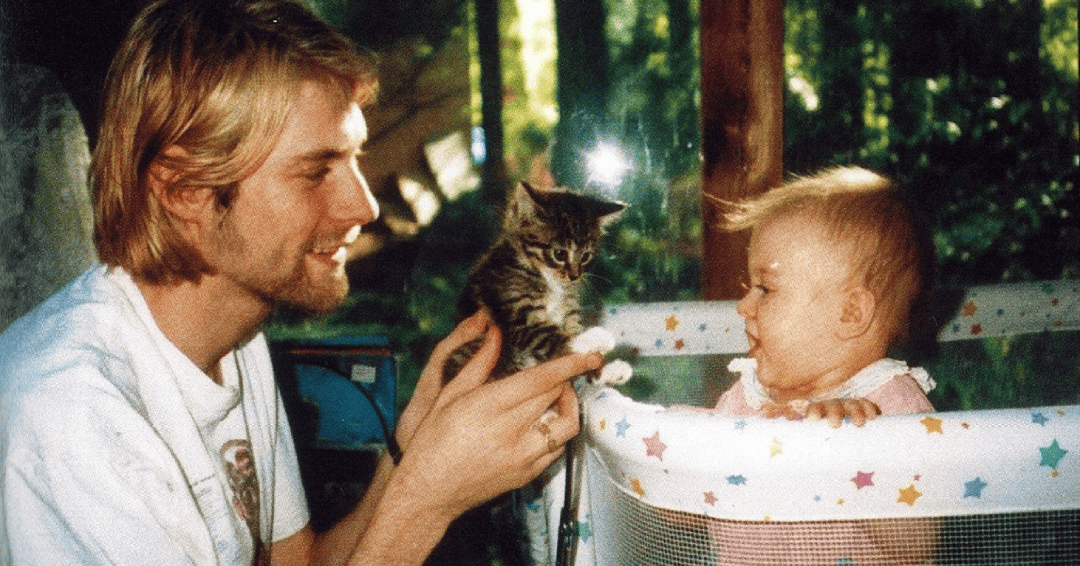

Cobain was a satirist with male supermodel looks and weapons-grade talent. The fact he was an artist and a musician was secondary. His music was satirical; his illustration was satirical; his humour was satirical. It just happened to include a guitar occasionally. As the Guardian noted and his bandmate Grohl described, he wasn't a mopey "emo" character at all:

He was brilliant, but he played dumb. And you know, Kurt was funny as shit. A lot of people don't realise that he was so hilarious. That guy's sense of humour wasn't from here. He was just very, very funny.

His original demo lyrics to the band's best-selling song mocked... being best-selling:

Well, I'm lying, and I'm famous

Here we are now, entertain us

I feel stupid and I'm famous

Here we are now, entertain us!

What followed his death was not satire, nor a measured forensic debate. It was thirty years of mythologising, amateur sleuthing, tabloid exploitation, and — on the other side — an equally fervent campaign of dismissal. The conspiracy camp built baroque theories of assassination. The debunkers waved them away with the confidence of people who had never read a toxicology report. Between them, the actual forensic question — a question of chemistry, physiology, and mechanical physics — rotted like the undeveloped rolls of 35mm film left sitting in an evidence locker for two decades.

A new paper, published in late 2025 in the International Journal of Forensic Sciences, attempts a multidisciplinary reconstruction of the death. It is authored by Bryan Burnett, a forensic microscopist, alongside firearms experts, toxicologists, and a handwriting analyst. It concludes, without equivocation, Cobain was murdered. The paper has attracted the predictable whirlpool of breathless coverage and reflexive dismissal associated with easy money and publicity. Both responses miss the point entirely.

The paper does not prove homicide.

But it does something more interesting and more dangerous to institutional complacency. It identifies, with unusual precision, the exact point where certainty collapses — and it reveals a question so elementary, so answerable, and so conspicuously unanswered, you will wonder why nobody has bothered to resolve it in three decades.

Facts, as John Adams observed, are stubborn things. And whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence. The evidence in this case is stubborn in a different way. It is incomplete, partially inaccessible, and ambiguous at the single point where ambiguity matters most. And the reason it remains ambiguous is not corruption, not conspiracy, and not scientific impossibility. It is institutional inertia — the quiet, grinding refusal of bureaucracies to revisit decisions once made, even when the basis for those decisions has never been publicly substantiated.

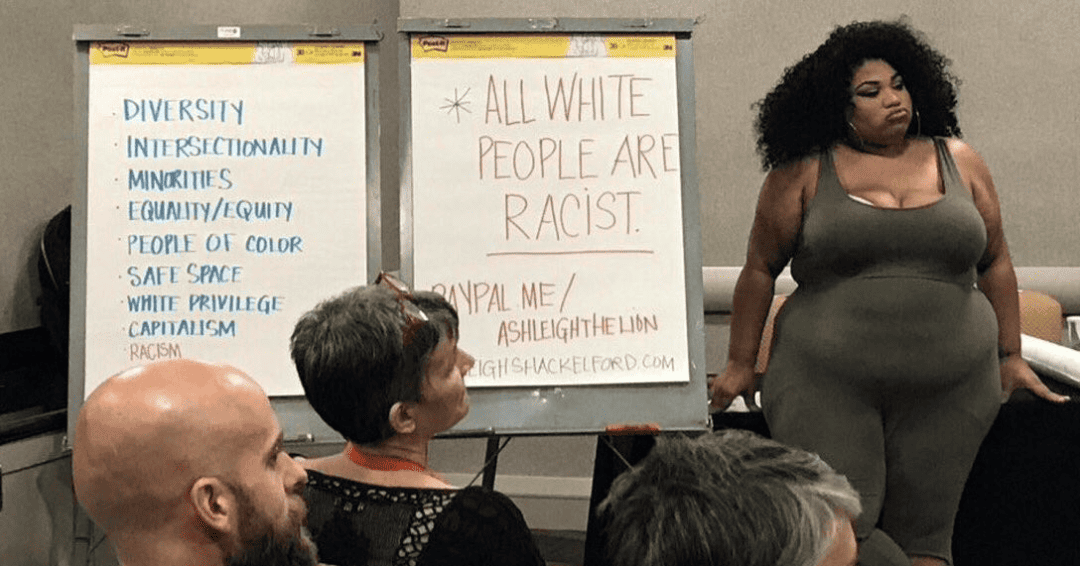

This is an attempt to think clearly about an ugly problem, while being respectful to an weary daughter whose father never got to experience her staggering physical beauty. Not to advocate. Not to debunk. To apply, with serious gravity, the decision architecture a forensic investigator would use when sitting in front of a scene where the dead cannot speak, the living may have reasons to mislead, and every self-appointed narrator — from every direction — must be treated as unreliable until the physical evidence says otherwise.

There are three possibilities. Only three. One of them is true. And the way you distinguish between them is not by choosing the story you prefer but by identifying the variables which differentiate the hypotheses, testing each variable against the physical record, and then — and only then — asking which configuration of evidence is explained most economically by which hypothesis.

Debunker's Fallacy and Conspiracy Mirror

The conspiracy theorists — the Tom Grant acolytes, the Reddit forensic detectives, the documentary-circuit advocates — have spent three decades building a prosecution case. They begin with the conclusion (homicide) and interpret every anomaly as supporting evidence. Every ambiguity becomes sinister. Every procedural shortfall becomes cover-up. Every unanswered question becomes proof of concealment. This is not investigation. It is advocacy, and it violates the most basic principle of forensic reasoning: conclusions must emerge from evidence, not precede it.

The Burnett paper, for all its technical sophistication, commits this error structurally. Its abstract declares Cobain "was a homicide victim" before the reader encounters a single piece of evidence. The entire document is organised as a prosecution brief — identify anomaly, propose homicide-compatible explanation, treat compatibility as probative. But compatibility is not proof. Many suicide scenes contain anomalies. Forensic science deals in probabilities, not in selecting the most dramatic explanation for each individual datum.

There was sufficient time from when the death occurred bloodstains on April 5 to finding the body on April 8 for the cleanup of at the actual shooting site and blood trail from the location of the homicide to the greenhouse floor where the body was found. The evidence shows that Kurt Cobain was not a suicide victim.

But the debunkers commit an equal and opposite error: they treat the official ruling as though it were a scientific conclusion rather than an administrative decision made under time pressure by a thirty-year-old assistant medical examiner, Dr. Nikolas Hartshome, who was not yet board-certified. They deploy the word "official" as though it conferred epistemic authority. They mock doubters as conspiracy theorists without engaging the specific physical observations — the casing ejection, the blood distribution, the compensator orientation — which are not speculative claims but documented features of the evidence record.

The debunker's fallacy is this: because the conspiracy theorists are often wrong, the official conclusion must be right. But the quality of your opponents' reasoning has no bearing on the quality of your own. A flawed challenge to a flawed determination does not make the determination sound. It makes the entire discourse unsound.

What neither camp will tolerate is the genuinely difficult position — the one occupied by honest forensic professionals — which is this:

- the evidence admits multiple interpretations,

- the primary records remain substantially inaccessible, and

- no responsible conclusion can be drawn without resolving a single, elementary, answerable factual question.

Violent Self-Inflicted Death: What "Normal" Is

Before examining any evidence specific to this case, it is necessary to understand the statistical territory in which it sits — because most people, including most commentators on this death, have no idea what firearm suicides involving drugs actually look like, and their ignorance distorts every judgement they make.

In the United States, approximately 27,000 people die by firearm suicide each year — more than die by firearm homicide. Firearms account for over 55 per cent of all suicide deaths. Nearly six in ten gun deaths in America are self-inflicted. Among male suicide decedents, firearms are the method in over 60 per cent of cases.

Roughly one in five suicide decedents tests positive for opiates at autopsy. Approximately 22 per cent of suicide deaths involve acute alcohol intoxication. Substance use disorders are associated with a five-fold increase in suicide mortality; opioid use disorders specifically carry a standardised mortality ratio for suicide of 5.46. People who inject drugs face a fourteen-fold elevated risk of death by suicide compared to the general population.

Shotgun suicides, though less common than handgun suicides, are well-documented in the forensic literature. They are associated with male decedents, rural or suburban settings, familiarity with long guns, and a desire for certainty of outcome. Long-gun suicides are slightly more common in the American West and Pacific Northwest. They are not exotic. They are not inherently suspicious. Up to 35% of gun suicides involve a shotgun. They are, in the cold calculus of death investigation, ordinary.

The reason this context matters is this: a male heroin user in his late twenties with documented suicidal ideation, a recent serious overdose, and access to a shotgun, found dead of an intraoral shotgun wound in a private setting with a farewell document nearby, is not a statistical anomaly. He is a textbook presentation. Every variable — sex, age, substance use, prior attempt, means availability, isolation, farewell communication — falls squarely within the established epidemiological profile of firearm suicide.

This does not prove suicide. Statistical profiles describe populations, not individuals. But it establishes the base rate — the starting probability before any case-specific evidence is examined. And the base rate is high. Very high. Any hypothesis purporting to displace it must contend with physical evidence powerful enough to overcome a prior probability which is, on the epidemiological merits alone, formidable.

Three Doors, and Only Three

The manner-of-death categories available to an American medical examiner are five: natural, accident, suicide, homicide, and undetermined. Natural is excluded by the gunshot wound. This leaves four — but "undetermined" is not a theory of events; it is an admission of insufficient evidence to choose among the others. The honest analytical space contains three competing hypotheses.

- Suicide. Cobain injected heroin, remained functional long enough to pack away the syringe and paraphernalia, relocated to his final position, placed the shotgun muzzle in his mouth, and pulled the trigger.

- Homicide. An assailant or assailants administered heroin to Cobain — by force, by deception, or by exploiting his willingness to use — and, once he was incapacitated, placed the shotgun in his mouth and fired. The scene was then arranged to resemble a suicide.

- Accident. Cobain, heavily intoxicated on heroin and diazepam, handled the loaded shotgun with impaired motor control, and it discharged. The scene was not staged; it simply looked odd because accidental intraoral discharges in heavily drugged people are inherently odd.

Each hypothesis must be tested against every piece of physical evidence, independently, without loyalty to any prior belief. The moment you lock yourself behind one door, you stop investigating and start prosecuting. The conspiracy camp locked their door decades ago. The debunkers locked theirs. Both have been arguing about wallpaper while refusing to examine the hinges.

What the Physical Evidence Actually Shows

What follows is not a decision tree. It is a systematic examination of the physical variables in the evidence record — the stubborn, awkward, incomplete facts against which all three hypotheses must be measured. The decision tree comes later, once the variables have been laid out and their individual diagnostic power assessed.

Variable 1: The Psychology of the Deceased

When experienced investigators encounter a violent death, they ask a question the public rarely considers: does this death make sense inside this life?

By early 1994, Kurt Cobain's existence had contracted into a pattern clinical psychologists recognise as suicidal constriction: chronic unresolved pain, escalating substance dependence, alienation from the creative identity central to his selfhood, a marriage characterised by volatility, and an exhaustion with fame so pervasive it saturated his private writings and public statements. In March 1994, he was hospitalised in Rome after ingesting a large quantity of Rohypnol and champagne — described by the attending physician as a serious suicide attempt, though his representatives called it accidental. He subsequently entered and left Exodus Recovery Center rehabilitation facility in in Marina del Rey, Los Angeles. He was twenty-seven, and by every account from people who knew him, profoundly tired of being alive.

The note found at the scene — whatever one makes of its disputed final four lines — contains passages immediately recognisable to anyone familiar with the phenomenology of suicidal ideation. The voice is not dramatic. It is weary. It speaks of losing passion for music, of feeling fraudulent on stage, of envying people capable of enjoying simple pleasures. This is the language of a man describing a spiritual death already completed, accounting for himself before the physical act catches up. Linguistic profiling analyses have found expressions of suicidal intent throughout the document, not only in the final lines.

IDiagnostic power: Very strong for suicide. The psychological profile maps precisely onto established models of suicidal behaviour. For homicide to remain viable, it must explain why a man whose documented mental state was driving him toward self-destruction was killed by someone else in a manner indistinguishable from what his own psychology was producing. For accident, the note is problematic — unless read as a farewell to music written independently of the death, which its main body could plausibly support. This variable does not close the other doors, but it makes them very heavy.

Variable 2: The Wound Characteristics

The entrance wound was on the superior (upper) hard palate, half an inch behind the front teeth. The pellet path ran at approximately thirty-five degrees to the body's long axis — shallower than the sixty degrees typical of intraoral suicides and shallower than the ninety degrees more often documented in intraoral homicides.

Thirty-five degrees is unusual. It matches neither textbook pattern cleanly.

Diagnostic power: Weak in all directions. An unusual angle does not discriminate between hypotheses on its own. It is consistent with a self-inflicted shot by someone in an awkward position, a weapon thrust into the mouth of someone supine, or an impaired person mishandling a weapon. It is a data point, not a verdict.

Variable 3: The Shotgun Casing

The Remington M11 operates on a long-recoil mechanism. If the barrel is obstructed during discharge — by a hand gripping it, for example — the mechanism cannot complete the ejection cycle, and the spent casing remains trapped in the receiver. Test firings by the Burnett study group (the only replication study published to date) produced zero successful ejections across over thirty rounds fired with a hand gripping the barrel in the described position.

At the death scene, the spent casing was found not in the weapon but on a jacket beside the body.

Diagnostic power: Moderate tension with the suicide scenario as described. If Cobain's hand was where investigators said it was, the casing should have remained in the receiver. The tension admits mechanical alternatives — loosened grip, imprecise description of hand position, grip broken by recoil — none of which has been tested or documented. Under homicide, the casing was cycled and placed. Under accident, the grip may have been partial or absent.

This variable does not resolve the case, but it introduces a mechanical anomaly into a scene previously treated as unremarkable.

Variable 4: The Blood Distribution

Backspatter — blood ejected from the entrance wound back toward the weapon during a contact-range head discharge — is one of the most experimentally verified phenomena in wound ballistics. Photographs of the shotgun show dried blood encrusted in the dorsal (trigger-side-down) compensator vents. The ventral surface (trigger-side-up — the weapon's position when found) shows none. The weapon was trigger-down at the moment of discharge and trigger-up when discovered.

Cobain's left hand, allegedly gripping the barrel near the compensator during discharge, shows no backspatter on its dorsal surfaces. It shows a single oval transfer stain on the thumb, consistent with the hand being placed on an already-bloody surface after the shot.

Diagnostic power: Moderate to strong tension with the suicide scenario. The pattern is more naturally explained by a sequence in which the weapon was flipped and the hand placed on it after discharge. Under homicide, this is staging. Under suicide, it requires either complex recoil dynamics not otherwise documented for this weapon, or post-discharge repositioning by the dying man. Under accident, the chaotic body-weapon relationship of an unintended discharge could produce unpredictable blood patterns, but the specific combination of clean hand plus transfer stain is difficult to reconcile with an unintentional discharge.

Variable 5: The Toxicology — The Crux

The toxicology report recorded a blood morphine concentration of 1.52 mg/L, with the presence of 6-monoacetylmorphine confirming recent heroin use, and diazepam with its metabolite nordiazepam.

Whether Cobain could have performed the suicide sequence — recapping a syringe, tidying a cigar box, relocating across a room, positioning a four-foot shotgun, inserting the compensator into his mouth until it contacted his hard palate, and pulling the trigger — depends entirely on what the number 1.52 mg/L represents.

Blood morphine exists in two forms. Free morphine is the unconjugated, pharmacologically active molecule — the substance binding to opioid receptors in the brain and producing euphoria, sedation, respiratory depression, and motor impairment. Total morphine includes free morphine plus its glucuronide-bound metabolites: morphine-3-glucuronide (largely inert) and morphine-6-glucuronide (which retains significant opioid activity but behaves differently at the receptor). In a post-mortem sample, free morphine typically constitutes 20 to 30 per cent of the total.

For the lay reader, the distinction works like this: imagine measuring alcohol in blood. One test tells you the total amount of ethanol and all its breakdown products combined. Another tells you only the ethanol still active in the brain — the part making you drunk. Both numbers are "blood alcohol." They describe very different things. A person whose total reading is high but whose active reading is moderate may be impaired but functional. A person whose active reading matches the total — meaning the drug is all still working, not yet metabolised — is in a radically different physiological state.

If 1.52 mg/L is total morphine — and the available evidence suggests a screening assay, which yields total morphine — the pharmacologically active fraction would sit roughly between 0.3 and 0.5 mg/L. The Meissner study (Forensic Science International, 2002), comparing 207 heroin-related deaths against 27 surviving intoxicated drivers, found surviving drivers with total morphine levels as high as 2.11 mg/L. A total morphine reading of 1.52 mg/L sits at the upper edge of the documented survivable range — extremely high, but within the boundary where chronic users have been documented as conscious and even operating vehicles.

If 1.52 mg/L is free morphine, the picture transforms catastrophically.

Meissner found every case with free morphine above 0.2 mg/L ended in death. The highest surviving free morphine level among intoxicated drivers was 0.128 mg/L. A free morphine reading of 1.52 mg/L would genuinely represent 11.9x times the threshold above which no survivor has been recorded (1.52 mg/L ÷ 0.128 mg/L= 11.875, or at 0.2 mg/L the multiplier would be 7.6) — a degree of receptor saturation so extreme it is difficult to imagine the subject performing any voluntary coordinated action whatsoever.

The distance between these interpretations is not a nuance. It is a chasm wide enough to swallow the entire case. And nobody — not the medical examiner, not the police, not the conspiracy theorists, not the debunkers, not the authors of any published paper — has established publicly which measurement was taken.

There is a further complication.

After death, drugs migrate from organs into the blood — a phenomenon called post-mortem redistribution. The degree of redistribution depends on the drug, the blood sampling site, the post-mortem interval, and the degree of decomposition. Cobain's body lay undiscovered for three days. If the blood was drawn from a central rather than peripheral site, the measured concentration may have been artificially elevated above the true level at the time of death. Whether peripheral blood was sampled — the forensic standard — is not publicly known.

Diagnostic power: Potentially decisive, but currently unresolved. If the true pharmacologically active morphine level was moderate (consistent with total morphine reading and chronic tolerance), the suicide sequence is physiologically strained but not impossible. If it was extreme (consistent with a free morphine reading or low tolerance), the sequence becomes extraordinarily implausible — approaching the boundary where the body contradicts the hypothesis. This variable is the crux of the entire case, and it cannot be evaluated without the original laboratory report.

Variable 6: The Suicide Note

The note is written on a restaurant placemat in red ink, addressed to "Boddah" (Cobain's childhood imaginary friend). Its main body is a weary, philosophical farewell to music and creative life. Its final four lines pivot to direct address — wife, daughter — and express finality. These lines are written in a noticeably different hand (larger, less controlled, tonally distinct). A forensic document examiner found "significant and notable" differences between the sections without making a conclusive second-author attribution. Linguistic profiling found suicidal intent throughout.

It is, definitely, strange. The entire transcription is odd, particular the praise for his "goddess wife" who, by all accounts, was staggeringly conflict-prone, introduced him to drug addiction, and is a thoroughly nasty piece of work. Their daughter's intense difficulties dealing with her are publicly documented. And the lawsuits involving them both are utterly bizarre.

To Boddah Speaking from the tongue of an experienced simpleton who obviously would rather be an emasculated, infantile complain-ee. This note should be pretty easy to understand. All the warnings from the punk rock 101 courses over the years, since my first introduction to the, shall we say, ethics involved with independence and the embracement of your community has proven to be very true. I haven't felt the excitement of listening to as well as creating music along with reading and writing for too many years now. I feel guity beyond words about these things. For example when we're back stage and the lights go out and the manic roar of the crowds begins., it doesn't affect me the way in which it did for Freddie Mercury, who seemed to love, relish in the the love and adoration from the crowd which is something I totally admire and envy. The fact is, I can't fool you, any one of you. It simply isn't fair to you or me. The worst crime I can think of would be to rip people off by faking it and pretending as if I'm having 100% fun. Sometimes I feel as if I should have a punch-in time clock before I walk out on stage. I've tried everything within my power to appreciate it (and I do,God, believe me I do, but it's not enough). I appreciate the fact that I and we have affected and entertained a lot of people. It must be one of those narcissists who only appreciate things when they're gone. I'm too sensitive. I need to be slightly numb in order to regain the enthusiasms I once had as a child. On our last 3 tours, I've had a much better appreciation for all the people I've known personally, and as fans of our music, but I still can't get over the frustration, the guilt and empathy I have for everyone. There's good in all of us and I think I simply love people too much, so much that it makes me feel too fucking sad. The sad little, sensitive, unappreciative, Pisces, Jesus man. Why don't you just enjoy it? I don't know! I have a goddess of a wife who sweats ambition and empathy and a daughter who reminds me too much of what i used to be, full of love and joy, kissing every person she meets because everyone is good and will do her no harm. And that terrifies me to the point to where I can barely function. I can't stand the thought of Frances becoming the miserable, self-destructive, death rocker that I've become. I have it good, very good, and I'm grateful, but since the age of seven, I've become hateful towards all humans in general. Only because it seems so easy for people to get along that have empathy. Only because I love and feel sorry for people too much I guess. Thank you all from the pit of my burning, nauseous stomach for your letters and concern during the past years. I'm too much of an erratic, moody baby! I don't have the passion anymore, and so remember, it's better to burn out than to fade away. Peace, love, empathy. Kurt Cobain Frances and Courtney, I'll be at your alter. Please keep going Courtney, for Frances. For her life, which will be so much happier without me. I LOVE YOU, I LOVE YOU!

Diagnostic power: Strong for suicide. Psychologically authentic farewell documents are extremely difficult to fabricate in a way which survives both forensic handwriting analysis and linguistic profiling. Under homicide, the note must be either genuine (with the final four lines added by the assailant, which requires access, handwriting skill, and foreknowledge of tone) or entirely fabricated to a standard capable of deceiving both intimate associates and forensic analysts. Under accident, the note is coincidental — written independently as a farewell to music, not to life. The first reading is parsimonious. The second requires extraordinary craftsmanship. The third is possible but uncomfortable.

The Pseudo-Decision Tree: Weighing Doors

Now — and only now — does the investigator step back from the individual variables and ask the architectural question: given these six variables, taken together, which hypothesis is supported most economically?

Think of each variable as a weight on a scale. The scale has three pans — suicide, homicide, accident. Some weights load heavily into one pan. Some distribute across two. Some are inconclusive and load nowhere. The question is not whether any single weight is dispositive but which pan, when all weights are placed, sits lowest.

Suicide receives the heaviest loading from Variables 1 (psychology) and 6 (farewell document). It receives moderate support from Variable 2 (wound characteristics are consistent, if not typical). It experiences tension from Variables 3 (casing), 4 (blood distribution), and 5 (toxicology — but only if the active morphine level was extreme). Its weaknesses are mechanical anomalies and physiological strain. Its strength is overwhelming psychological and statistical coherence.

Homicide receives support from Variables 3 and 4, where the physical evidence is more naturally explained by post-discharge scene manipulation. It receives conditional support from Variable 5 — but only if the morphine level demonstrates incapacitation. It is burdened by Variables 1 and 6, which it must explain away or absorb. And it carries a structural weight no variable can measure: the generated complexity of the alternative agent.

Here the investigator must be ruthlessly honest about what the homicide hypothesis actually requires.

It requires an assailant — or more probably, multiple assailants — who:

- Gained access to a private residence

- Administered a massive heroin dose to a person either:

- by force (requiring physical control of a conscious, if impaired, adult male) or

- by deception (requiring the victim to accept an injection from someone other than himself, using an atypical syringe, in an atypical injection site, through his clothing).

It requires this assailant(s) to:

- Have waited for incapacitation

- Positioned a four-foot shotgun in the victim's mouth

- Fired it

- Repositioned the weapon

- Wiped blood from the barrel

- Placed the dead man's left hand on the bloody barrel

- Planted the ejected casing

- Ensured the presence of a plausible suicide note (either pre-existing or fabricated to a standard capable of surviving forensic scrutiny)

- Arranged the drug paraphernalia

- Exited the locked greenhouse

- Left no fingerprints,

- Left no DNA

- Left no trace evidence

- Left no witness testimony, and

- Maintained silence for over thirty years.

Each element of this chain is individually possible. Murders have been staged before. People have maintained silence before. Forensic evidence has been missed before.

But the investigator's question is not whether each link is possible. It is whether the chain is more probable than the alternative.

And the honest answer is: the homicide hypothesis requires an external agent of extraordinary sophistication — a person or persons capable of executing a complex physical staging, a forensic counter-operation, and a decades-long silence, all targeted at a victim whose psychological profile was already producing the exact outcome the staging was designed to simulate.

The hypothesis does not merely require a murderer. It requires a murderer of unusual skill, operating against a victim whose own trajectory was converging on the same destination, in a manner leaving no physical trace positively inconsistent with suicide.

Occam's Razor — properly applied — does not mean "choose the simplest-looking explanation." It means: prefer the hypothesis requiring the fewest unsupported assumptions. The suicide hypothesis has anomalies. The homicide hypothesis has a dependency chain of extraordinary length, every link of which must hold simultaneously.

Accident receives weak support from the toxicological impairment (a heavily drugged person mishandling a weapon) and can accommodate the unusual wound angle. It is burdened by the suicide note, which is very difficult to reconcile with unintentional death. Its probability is low but not zero, and an investigator who refuses to place it on the table has already been captured by the dramatic framing of the case.

The honest terminal assessment: suicide remains the most probable hypothesis by a significant margin, with residual anomalies in the physical evidence which have not been adequately investigated and which would benefit from examination of the original forensic records.

The homicide hypothesis is not excluded but carries a burden of generated complexity so heavy it requires extraordinary physical evidence to remain viable — evidence which has not been produced. The accident hypothesis is the weakest of the three but cannot be formally eliminated.

And the entire assessment pivots on Variable 5 — the toxicology — because it is the one variable capable of shifting the probability mass dramatically. If the pharmacologically active morphine level was extreme, the suicide sequence moves from "physiologically strained" to "approaching physical impossibility," and the generated complexity of the homicide hypothesis becomes less prohibitive relative to the mechanical implausibility of the alternative.

The Paper, the Industry, and the War of False Certainties

The paper published in the International Journal of Forensic Sciences concludes, in its abstract, before the reader has encountered a single piece of evidence: "Kurt Cobain, based solely on publicly available discovery and analysed through a multidisciplinary critical method, was a homicide victim."

This is not the language of science. Science does not deal in certainty. It is an academic lawsuit.

The paper contains technically interesting work. The shotgun cycling experiments are legitimate forensic methodology. The bloodstain observations, while constrained by image quality, apply sound analytical principles. The toxicological discussion is competent.

But the paper is structurally compromised by a flaw any peer reviewer would identify in the first paragraph: it is hypothesis-led, not evidence-led. The conclusion precedes the analysis. Every ambiguous finding is interpreted through the perspective of homicide compatibility — and compatibility is treated as probative. This is prosecution reasoning, not forensic reasoning. A finding compatible with homicide is not evidence of homicide. Many findings are compatible with multiple hypotheses. The task of forensic science is not to identify compatibility but to assess differential diagnostic power — which findings discriminate between hypotheses, and which do not. Ask Dr. Gregory House, M.D.

The paper also builds on incomplete primary evidence and repeatedly acknowledges as much:

Definitive conclusions can only be drawn by a thorough review of the full data... At present, this information is not available.

You cannot overturn a manner-of-death determination using partial records. You can identify reasons to seek the full records. These are very different things.

On the opposite side of the trench, the debunking industry treats the official ruling as though it were a scientific conclusion. It deploys the word "official" as though it conferred epistemic authority. It mocks doubters as "conspiracy theorists" without engaging the specific physical observations — the casing ejection mechanics, the blood distribution, the compensator orientation — which are not speculative claims but documented features of the evidence record.

What neither camp can tolerate is the position occupied by honest forensic professionals: the evidence admits multiple interpretations, the primary records remain substantially inaccessible, and the single most important factual question — what the morphine measurement actually represents — has never been publicly answered.

Both camps are selling certainty they have not earned. The conspiracy industry profits from doubt. The debunking industry profits from closure. The dead man has no representative in either market.

The File in the Cabinet

Everything narrows to this.

The distinction between free and total morphine is not a philosophical puzzle. It is a laboratory measurement. It was measurable in 1994 using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, which was standard forensic laboratory equipment by the mid-1980s. Whether King County's laboratory performed confirmatory testing — and what the result was — is a matter of opening a file.

The toxicology report accompanying the widely circulated autopsy report appears to be a summary. Whether a more detailed laboratory analysis exists behind it — specifying the analytes measured, the methodology employed, the blood sampling site, and the confirmatory results — is not a scientific question. It is an administrative one. The report is held by the King County Medical Examiner's Office archive. It is a historical medico-legal record, over thirty years old. Washington State maintains a strong public records framework.

- If the complete report reveals a screening-derived total morphine figure with no confirmatory free morphine measurement, the ambiguity becomes intrinsic and permanent. The 1.52 mg/L figure would remain a blunt instrument — informative enough to confirm an extraordinary amount of heroin in the system, too imprecise to determine what it was doing to the brain at the moment the trigger was pulled. The debate, in its current form, would be formally unresolvable. Both camps would be revealed as having argued for decades about a number whose meaning was never established.

- If the report reveals a confirmatory free morphine figure consistent with functional capacity in a tolerant user — say, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/L — then the physiological objection to the suicide sequence weakens substantially, and the residual physical anomalies (casing position, blood distribution) remain unexplained but insufficient to override the weight of the psychological, statistical, and documentary evidence.

- If the report reveals a free morphine concentration so high as to make voluntary coordinated action essentially inconceivable — anything approaching 1.0 mg/L or above — then every forensic toxicologist in the world sits up straight. The suicide sequence does not merely strain. The body contradicts the hypothesis. And when the body contradicts the hypothesis, the generated complexity of the alternative stops being prohibitive and starts being necessary — because the simple explanation has failed.

One number. Three possible outcomes. Each reshaping the evidentiary landscape so dramatically as to render three decades of secondary argumentation irrelevant.

The file is in a building in Seattle. It has been there since 1994. It is not classified. It is not sealed by court order. It is a table of numbers generated by a machine, held by a public office, subject to public records law.

The Duty of Precision

This is not, ultimately, about one famous death. Tens of thousands of Americans die by firearm suicide each year. The manner-of-death determination for each is made by a medical examiner or coroner, often under crushing caseloads, often with incomplete information, often by professionals whose workforce is in documented crisis. Forensic pathologist shortages are endemic across the United States.

If the King County Medical Examiner's Office — handling one of the most scrutinised deaths in modern history — may not have performed confirmatory toxicology on a case presenting an extraordinary blood morphine level combined with a mechanically complex firearm wound, what does this say about the evidentiary standards applied to the anonymous dead? To the heroin user found in a Tacoma apartment? To the veteran found in a rural garage with a shotgun and a bottle of whisky and no journalist who will ever ask whether the toxicology was screening or confirmatory?

Nobody reasonable is arguing cover-up. The far more likely explanation is the mundane one: an understaffed office, processing a high-profile death under immense pressure, made a rapid determination and moved on. The determination may be correct. It may even be obviously correct. But "obviously correct" and "properly substantiated" are not the same thing. The distance between them is where institutional failure lives — quiet, banal, and repeated tens of thousands of times a year in jurisdictions across the country.

The Cobain case is not important because Kurt Cobain was famous. It is important because his fame makes visible a species of investigative inadequacy normally invisible — the gap between a conclusion and its evidentiary foundation, papered over by the word "official" and enforced by the institutional reluctance to revisit decisions once filed.

Facts are stubborn things. The blood spoke in April 1994. The shotgun spoke. The body spoke. Whether anyone in a position of authority listened carefully enough — whether anyone measured with sufficient precision to know what the evidence actually said — is the question this case has always been about.

It has never been answered.

It can be.

And it should be — not for the sake of conspiracy, not for the sake of closure, but because the dead are owed precision, the living are owed honesty, and the difference between knowing and guessing is the difference between a justice system and a bureaucracy.

The file is in Seattle. The question is elementary. The technology to answer it existed before the man died. The only thing missing, for thirty-one years, has been the will to ask.

And we'll publish it when they send it to us in a few months.