China Establishes Its First Colonial Base In England

Secret police stations. Bounties on British residents. A consul-general filmed beating a protester on camera. And now: 208 basement rooms beneath the City's financial spine, with a wall to demolish one metre from our data cables. The Prime Minister's response? Approval—timed for his trip to Beijing.

Imagine, for a moment, the brass-necked audacity of it. A strategic adversary—one running secret police stations on your soil, placing bounties on your residents, whose consul-general was filmed pulling a British resident's hair before having him beaten inside diplomatic grounds—asks to build the largest embassy in Europe directly on top of the cables carrying your financial system's lifeblood.

And you say yes.

Not reluctantly. Not after extracting concessions. Not with visible disgust at the request itself. You say yes because you have a trip planned to Beijing and don't want it to be awkward.

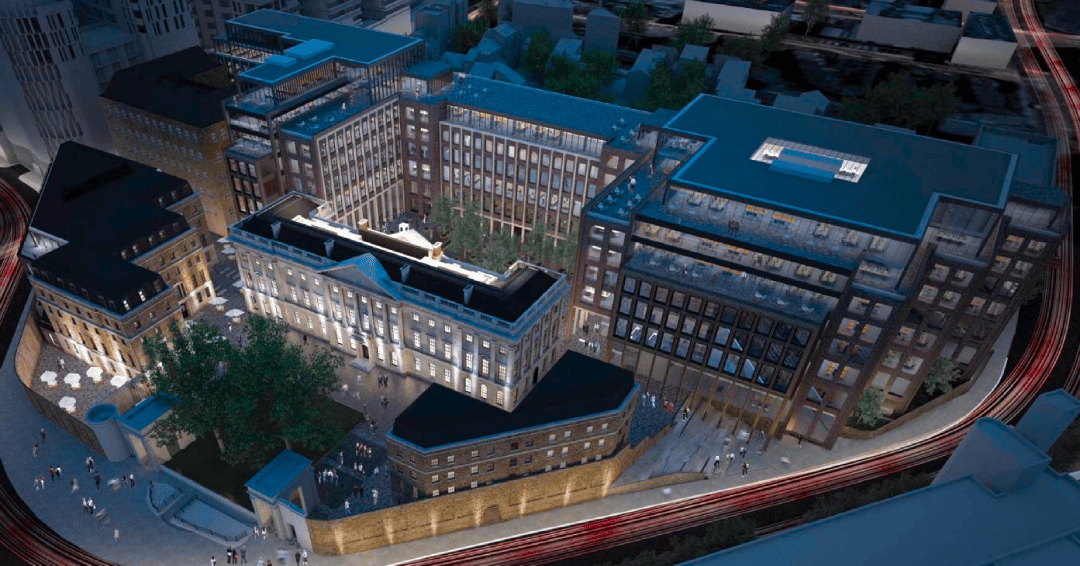

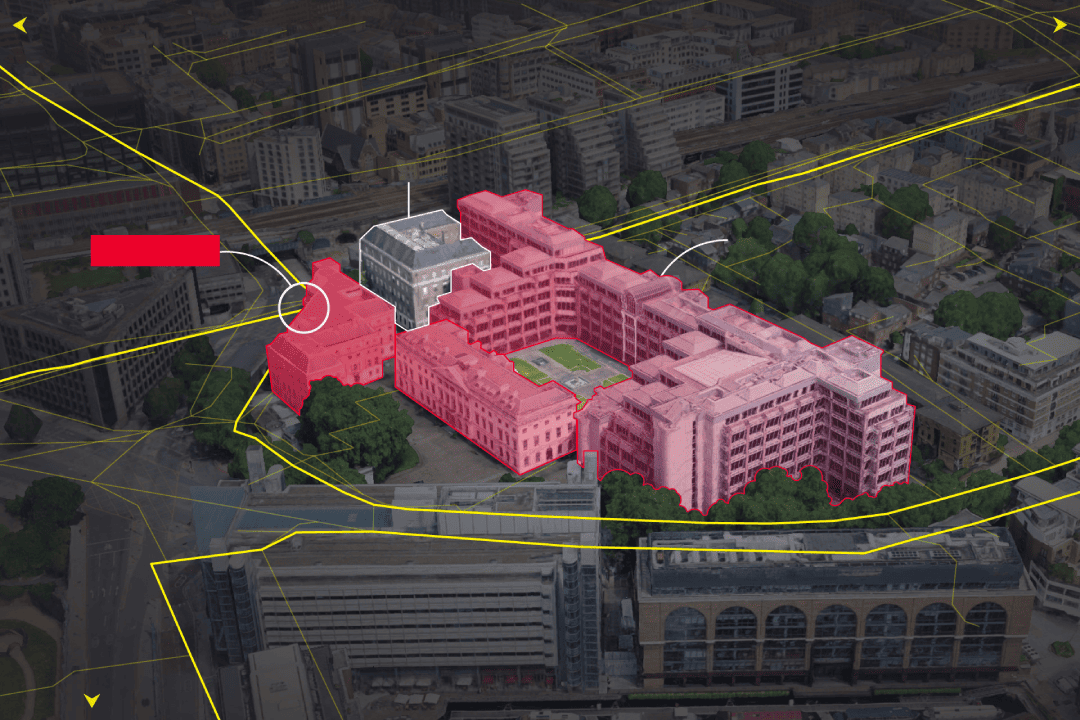

This is Britain in January 2026. The site is Royal Mint Court, where we once stamped the currency of empire. The irony is beyond satire. China purchased this 22,000-square-metre plot in 2018 for £255 million under Boris Johnson and his Chinese-loving father's approval — money from the Crown Estate, no less—and has spent the intervening years grinding through planning objections while the British establishment tied itself in procedural knots pretending this was merely a question of building regulations.

The unredacted blueprints, obtained by the Telegraph, reveal 208 basement rooms. A triangular concealed chamber forty metres across, fitted with hot-air extraction systems capable of cooling extensive computing equipment. An outer wall to be demolished and rebuilt one metre from the fibre-optic cables connecting the City to Canary Wharf. The cables belonging to BT, Colt, and Verizon. The cables carrying every bank transfer, every trading instruction, every encrypted communication in the financial capital of Europe.

This is not espionage risk. This is espionage infrastructure—purpose-built, diplomatically protected, and about to receive the Prime Minister's blessing.

The Consul-General Who Admitted It Was His "Duty" To Assault a British Resident

Before we discuss the super-embassy, let us establish what Beijing believes it can do on British soil—because they have already shown us.

In October 2022, protesters gathered outside the Chinese Consulate in Manchester to mark the opening of the Communist Party congress. They carried satirical images of Xi Jinping. Masked men emerged from the consulate, tore down the banners, and dragged a protester named Bob Chan through the gates onto diplomatic ground. They beat him as he lay on the pavement. Video shows multiple men kicking and punching him while a grey-haired figure in a blue beret—later identified as Consul-General Zheng Xiyuan—pulled his hair.

British police had to physically enter the consulate grounds to extract Chan. He was hospitalised with cuts, bruises, and clumps of hair torn from his scalp.

When confronted by Sky News, Zheng did not deny his involvement. He admitted pulling Chan's hair. "The man abused my country, my leader," he said. "I think it's my duty."

His duty. On British soil. Against a British resident exercising his legal right to protest.

Six Chinese officials were eventually recalled to China rather than face police questioning—because they refused to waive diplomatic immunity. No prosecutions followed. The message was clear: we can assault your residents in broad daylight, film ourselves doing it, admit it on television, and suffer no meaningful consequence.

Now Britain is considering whether to give these same people a fortress-sized complex beside the City's communications infrastructure.

Bounties, Secret Police, and the Hunting of British Residents

In July 2023, Hong Kong authorities announced bounties of one million Hong Kong dollars—approximately £100,000—for information leading to the arrest of eight pro-democracy activists living in exile in Britain, America, and Australia.

Their alleged crimes? Calling for sanctions against Chinese officials, advocating for Hong Kong's autonomy, and speaking to foreign media. Activities legally protected in every democracy on earth.

By December 2023, the list had grown to thirteen names. The bounties remain active. Nathan Law, a former Hong Kong legislator now living in London, woke one morning to find his face on wanted posters offering a fortune to anyone willing to betray him. "They will pursue me for life," he said. He was not being dramatic; Hong Kong police explicitly stated this was their intention.

Meanwhile, Safeguard Defenders—a Spanish human rights organisation—documented fifty-four illegal Chinese "police service stations" operating across five continents. Three were in Britain: Croydon, Hendon, and Glasgow. The Glasgow station operated from a Cantonese restaurant whose proprietor had met Boris Johnson while he was Prime Minister.

The British government's technocratic-regulation response was characteristic. Parliamentary questions were tabled. Investigations were announced. Ministers promised to take the matter "extremely seriously." Eventually, in June 2023, Tom Tugendhat confirmed the stations had "closed permanently" after the government told China their presence was "unacceptable."

Let us pause on that word: unacceptable. China opened secret police stations in three British cities—stations the government itself acknowledged were designed to "worry and intimidate" those who had fled Chinese persecution—and our response was a polite request to close them.

The stations closed. The intimidation continued. The bounties remain. And now we propose to give Beijing 22,000 square metres of sovereign diplomatic territory in the heart of London.

Jimmy Lai: The British Citizen Rotting in a Chinese Prison While His Government Builds Their Embassy

While Sir Keir Starmer prepares his Beijing itinerary, a seventy-eight-year-old British citizen named Jimmy Lai sits in a Hong Kong prison cell with his fingernails falling off, his teeth rotting, and his health collapsing after more than 1,800 days in solitary confinement.

Lai's crime was running a newspaper.

Apple Daily, was shuttered in 2021 after police raided its offices and arrested its senior staff. Lai himself was convicted in December 2025 of "conspiracy to collude with foreign forces"—meaning he had spoken to Western journalists and met with American politicians, activities which would have been entirely unremarkable for any newspaper publisher anywhere in the free world.

He faces life imprisonment. His sentencing hearing began last week on 12 January 2026—the same week Britain is expected to approve China's super-embassy.

Human Rights Watch called the conviction "a travesty of justice." Amnesty International declared him a prisoner of conscience. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found his imprisonment unlawful. The Committee to Protect Journalists warned the "risk of him dying from ill health in prison increases as each day passes."

The British government's response? Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper summoned the Chinese ambassador to express concern. She used phrases like "politically motivated" and "deeply troubling."

Then she returned to approving planning permission for Beijing's intelligence headquarters, claiming it could bring "security advantages." HR was concerned. Beijing must have been terrified.

This is our leverage in action. This is British citizenship as a protective document. A man rots in prison for the crime of journalism while his government—the government who issued his passport—builds his jailers a palace.

Thirty Confucius Institutes and the Colonisation of British Student Minds

The super-embassy does not arrive in isolation. It sits atop a decade of systematic Chinese penetration of British institutions—a penetration our own Parliament has documented and our government has refused to stop.

Thirty Confucius Institutes operate on British university campuses. Funded by the Chinese government, nominally designed to "promote language and culture," they function as what Parliament's Intelligence and Security Committee called part of an ecosystem enabling "influence and intellectual property acquisition."

Staff are required to sign loyalty pledges to the Communist Party. Applicants must disclose their "political characteristics" and promise to abide by Chinese law while abroad. The UK-China Transparency organisation concluded British universities are "operating Confucius Institutes illegally and enabling transnational repression."

Rishi Sunak pledged to close them during his 2022 leadership campaign:

China and the Chinese Communist Party represent the largest threat to Britain and the world's security and prosperity this century,

None have closed. The government stopped direct funding in 2024, declared victory, and moved on. The institutes remain.

MI5 has briefed vice-chancellors on hostile state targeting of sensitive research. The National Cyber Security Centre has warned of knowledge transfer to entities linked to the People's Liberation Army. Parliament's own committee described universities as "a rich feeding ground" for influence operations. And yet the collaborations continue. The money flows. The dependencies deepen.

Meanwhile, Chinese students—whose fees universities have become addicted to—report being monitored by their own classmates, their social media scrutinised, their families back home pressured when they express heterodox opinions. The panopticon has been imported wholesale, and we charge them £25,000 a year for the privilege of living inside it.

The Cable Beneath Mansell Street: What 208 Basement Rooms Are Actually For

Now we arrive at the basement. The publicly released planning documents for Royal Mint Court arrived with large sections blacked out. China explained the redactions were for "security reasons." When pressed for clarification, Beijing declared it "not appropriate" to disclose every room layout.

The unredacted documents tell a different story.

Beneath the old Seamen's Registry building in the north-west corner of the site lies a triangular chamber up to forty metres across and two to three metres deep. Its exterior wall borders Mansell Street. According to the drawings, China intends to demolish this wall and rebuild it—construction work placing Chinese personnel just over one metre from the fibre-optic cables running beneath the pavement outside.

Those cables belong to BT Openreach, Colt Technologies, and Verizon Business. They form part of the London Internet Exchange—one of the largest internet exchange points on earth. They connect the Telehouse data centres in Docklands to hubs across the capital. They carry financial transaction data for every major City institution, email traffic for millions of users, and encrypted communications for government departments.

The chamber is fitted with hot-air extraction systems venting through an existing lightwell and a new grille. This implies the need to remove large volumes of heat—the kind generated by extensive computing infrastructure.

Professor Alan Woodward of the University of Surrey called the wall demolition a "red flag." His assessment:

If they wanted to tap the cables, they wouldn't need to go far. You wouldn't know what was happening down there.

Options for tapping include diverting cables, inserting wire taps, placing devices directly atop the fibre, or bending cables so light leaks through their casing to be read by specialised equipment. None of this requires breaking the law after construction is complete—because construction itself provides the access.

And once the embassy is operational? Diplomatic protections make meaningful inspection impossible.

The Reverse-Scenario Test That Ends All Debate

There is one question capable of dissolving every procedural excuse, every diplomatic platitude, every reassurance about security mitigations and consolidation advantages.

If Britain asked to build a super-embassy in Beijing, positioned beside Chinese critical infrastructure, with 208 basement rooms and redacted blueprints—would China approve it?

Ask yourself honestly. Picture a British delegation presenting drawings with large sections blacked out, explaining the redactions were for "security reasons," declining to specify the purpose of underground chambers fitted with cooling systems.

China would not review the application. It would not convene stakeholder consultations. It would not defer the decision three times while weighing diplomatic sensitivities.

It would say no—immediately, contemptuously, and with the confidence of a state that understands power.

Britain cannot bring itself to do the same.

This asymmetry explains everything. One side grasps that security is not a planning matter. The other side pretends it is—because acknowledging reality would require making a decision, and decisions invite criticism, and criticism is what this government fears more than strategic exposure.

The Century of Humiliation—And Who Humiliates Whom

The Chinese Communist Party has made the "Century of Humiliation" at British hands central to its founding mythology. From the First Opium War in 1839 to the Communist victory in 1949, China suffered at the hands of Western powers—and Britain, having started it all with gunboats and opium, bears special responsibility in this account.

British warships shelled Canton. British merchants flooded China with addictive drugs. British diplomats imposed unequal treaties at bayonet point. British soldiers looted and burned the Summer Palace in 1860. Hong Kong remained under British control until 1997.

This history is taught in every Chinese school. It is invoked by Xi Jinping in major speeches. It is the perspective through which the Party views all encounters with the West. President Xi has explicitly framed Hong Kong's return as ending "the humiliation and sorrow" of colonial occupation.

Now consider the view from Beijing. These people do not like us. At all.

Chinese state press makes it extremely clear their opinion towards Britain.

“British public opinion remains prejudiced against China and highly expects to embrace an opportunity to prove that it is superior compared with the emerging nation. Nevertheless, engaging in economic cooperation with Beijing is in its practical interests.” “Chinese society is more and more relaxed in dealing with Sino-UK ties, while the British could not be pettier,” the Global Times added, suggesting its readers take pity on this “old declining empire”.

A British Prime Minister is about to approve their largest spy embassy in Europe—a project the entire British national security establishment has flagged as an espionage risk and has horrified our closest allies —because he wants a smoother reception when he visits China and something-something-international law. British citizens with bounties on their heads continue living in fear while their government builds diplomatic facilities for their persecutors. A British newspaper publisher rots in prison while his nation wrings its hands and issues statements.

Who, precisely, is being humiliated now?

The Century of Humiliation ended because China became strong enough to say no. What does it mean when Britain can no longer say no to China?

The CPS Lawyer Who Became PM By Accident

Sir Keir Starmer spent his career at the Crown Prosecution Service, eventually rising to Director of Public Prosecutions. The role trained him in procedural caution, deference to process, and the avoidance of outcomes his lawyers couldn't defend. These are admirable qualities in a prosecutor.

They are catastrophic in a Prime Minister confronting adversarial statecraft.

Even the hapless Angela Rayner was given pause for thought, but the mass protests apparently haven't changed any minds. Nor has the cacophony of Labour MPs or the enormous noise from Washington. The latter is explicitly concerned after the Venona project revealed the extent of Soviet penetration of UK intelligence services.

The usual intelligence plants in the UK press have been doing the round to placate the plebs and their worries.

A CPS mentality treats every question as a legal risk to be managed rather than a strategic choice to be owned. It substitutes procedural correctness for outcome responsibility. It hides behind review mechanisms when faced with difficult decisions. It mistakes defensibility for wisdom.

Apply this temperament to the super-embassy and the result is predictable: the decision has been framed as quasi-judicial, responsibility diffused across officials and inspectors, political ownership evacuated. The approval will arrive not as a choice but as an inevitability—something that simply "happened" after process ran its course.

This is not leadership. It is abdication dressed as diligence.

Churchill, facing a different adversary, understood the logic of pre-emption—preventing future catastrophe justifies present difficulty. Thatcher, confronting Argentine aggression, grasped sovereignty is not subject to negotiation when the alternative is submission.

Neither would have entertained this proposal for five minutes. They would have recognised instantly what it was: a strategic competitor requesting a permanent advantage position on British soil, beside British infrastructure, under protections making British oversight impossible.

They would have said no—and dared Beijing to complain.

They would have been criticised internationally for about seventy-two hours. Then they would have been respected.

Sir Keir Starmer appears determined to be criticised forever for the opposite.

Constitutional Failure At Industrial Level

If the Prime Minister somehow approves this embassy—or permits its approval through ministerial proxies while maintaining plausible distance—he will have made a choice with constitutional implications no procedural framing can obscure.

The first duty of government is defence of the realm. This is not metaphor. It is the foundational premise legitimising the state's claim to authority. A government knowingly increasing systemic security exposure, limiting future oversight capacity, and doing so for diplomatic convenience is not fulfilling this duty. It is betraying it.

The betrayal is not dramatic. No secret allegiance exists. No ideological conversion has occurred. There is only the slow, banal accumulation of decisions prioritising reputation over security, process over judgment, approval over refusal.

The outcome is the same as infiltration—strategic advantage handed to an adversary—achieved through cowardice rather than conspiracy.

This is what makes the super-embassy decision constitutional rather than merely political. It tests whether the British state retains the capacity to prefer its own defence over its own comfort. It asks whether elected leaders can say no to a powerful foreign government when saying no is difficult and saying yes is easy.

On current evidence, the answer appears to be: they cannot.

Colonisation Without a Single Shot Fired

Countries spy on each other. Great powers accumulate leverage wherever leverage can be found. These are not accusations; they are descriptions of how the world works and has always worked.

The question is never whether adversaries will seek advantage—they will—but whether your own government will hand them advantages they could not otherwise obtain.

Britain is about to do precisely that.

Not through invasion. Not through coercion. Not through any confrontation the public could rally against. Through paperwork. Through planning inquiries. Through ministerial deferrals and security consultations and deadline extensions and, finally, through a quiet approval timed to smooth a diplomatic visit.

- They have placed bounties on British residents. We approve their embassy.

- They beat a protester on camera and called it their "duty." We approve their embassy.

- They ran secret police stations in our cities to intimidate refugees. We approve their embassy.

- They imprisoned a British citizen for running a newspaper and let his health collapse in solitary confinement. We approve their embassy.

- They redacted their blueprints, refused to explain their basements, positioned themselves one metre from our financial data spine, and fitted their hidden chambers with cooling systems for equipment they won't describe. We approve their embassy.

And the establishment will tell you the risks are managed. Security experts were consulted. Consolidation brings advantages.

What they will not tell you is why any serious state would permit this. What they will not tell you is why the obvious explanation—weakness, fear, capture—should be rejected in favour of the comfortable fiction which process produces wisdom.

A government that cannot say no to this cannot say no to anything. And a Prime Minister who treats national security as a planning matter while racing to Beijing for a handshake is not practicing statecraft.

He is practicing submission. And the whole country is watching.

Write to your MP. Demand answers. Refuse to accept the laundering of strategic surrender through bureaucratic procedure. The decision has not yet been made—and every day it remains unmade is a day when pressure matters.

This is not their country to give away. It is ours.