How England Became Ugly

Britain's landscape was not ruined by accident. A small class of ideologues, armed with continental doctrine and state power, waged a decades-long war on beauty — and the buildings they left behind still punish millions every day who no choice but to be demoralised by it. It's time to demolish them.

There is one art form you cannot walk away from. You may dislike a painting and leave the gallery. You may switch off the television, shut a novel, mute a song. Your aesthetic liberty is, in every other domain, entirely intact. But architecture surrounds you. It presses in at breakfast, at the bus stop, on the commute, from every window. You live inside it. You raise children inside it. You grow old, and eventually die, inside it.

When architecture is good — when it rises with proportion and warmth and a sense of accumulated care — it confers a kind of silent dignity upon daily life. The people of Bath do not think about architecture every morning. They simply feel, without articulating why, a background hum of belonging. The sandstone crescents and Georgian terraces are not museum pieces to them; they are the texture of ordinary existence. The same is true in the Cotswolds, in Edinburgh's New Town, in the cathedral closes of Salisbury and Wells. Beauty, when it is embedded in the built environment, becomes invisible — a kind of atmospheric generosity.

When architecture is bad — truly, systematically, ideologically bad — it does the opposite. It presses down on the spirit with a weight the occupant may never fully identify. Depression in tower blocks, anxiety on brutalist estates, a dull and nameless alienation in the vast identikit suburbs of the 1970s and 1980s: these are not coincidences. They are consequences. Architecture shapes behaviour more powerfully than almost any public policy, because it operates beneath conscious awareness. It is the wallpaper of the psyche.

And between 1945 and 1995, Britain embarked upon the most radical transformation of its built environment in recorded history. Not through war. Not through natural disaster. Through choice.

Through the deliberate, doctrinaire, bureaucratically administered choice of a small professional class, armed with foreign ideology, state funding, and an almost religious contempt for the traditions of the country they were reshaping.

The results stand all around us. They cannot easily be undone. And the British people — whose instinct for beauty is among the deepest in the Western world — were never asked.

Centuries of Unselfconscious Grace

English architecture, for centuries, had been one of the great organic achievements of European civilisation. It was not, by and large, the product of grand theory. It grew slowly, from the ground up, shaped by local geology, inherited craft, the peculiarities of climate and terrain, and the quiet preferences of people who expected to live among what they built. A Somerset village was built from Somerset stone. A Norfolk farmhouse reflected Norfolk's flat, wind-raked landscape. A London terrace expressed, in its proportions and its brick, something deeply specific about London.

This was architecture as cultural inheritance — not imposed, but accumulated. Each generation added, amended, extended. Beauty was not the declared objective. It emerged as a byproduct of permanence, continuity, and the friction of human skill applied repeatedly over long periods. The builder who laid a lintel in 1780 did not consult a manifesto. He followed a pattern refined over generations by men who cared, practically and commercially, about getting it right — because their name was on the work, and their neighbours would see it every day.

The result was a built landscape of extraordinary richness. Not uniform. Not designed from above. But coherent, because it grew from shared assumptions about proportion, scale, and the relationship between building and place.

Bath was not planned by a committee optimising housing units per hectare. It was the vision of John Wood the Elder and his son the Younger, working within classical tradition to produce something ravishingly harmonious. The great cathedrals were not erected according to cost-per-unit metrics. They were acts of faith rendered in stone, built by men who expected their grandchildren's grandchildren to worship beneath those vaults.

Even humbler structures — the market towns, the parish churches, the coaching inns — possessed a beauty born of care. Materials were local. Scale was human. Ornament was restrained but present. The England of 1939, for all its social problems, retained a built environment shaped by centuries of organic evolution.

Within a single generation, much of it would be swept away.

Continental Doctrines and the Architects Who Imported Them

The uglification of Britain did not originate in Britain. Its intellectual roots lay in a movement born between the 1890s and 1930s in continental Europe — a movement shaped by industrialisation, political revolution, and a philosophical hostility to inherited tradition so thoroughgoing it amounted to a kind of civilisational self-harm.

It began, as revolutions often do, with a manifesto. In 1908, the Austrian architect Adolf Loos published an essay with the chillingly confident title Ornament and Crime. His argument was blunt: decoration was a mark of primitive societies. Civilised people, Loos insisted, would strip it away. Ornament wasted labour and materials. It masked structural truth. It was, in his word, degeneracy.

This was not idle provocation. Loos meant every syllable. And his ideas travelled. They infected a generation of architects who found, in the rejection of beauty, a moral thrill — the intoxicating sensation of believing oneself more advanced than every preceding century.

Then came Walter Gropius.

In 1919, in the wreckage of defeated Weimar Germany, he founded the Bauhaus — not merely an architectural school but a civilisational project. The Bauhaus set out to redesign society itself. Art must serve industry. Buildings must be standardised, machine-like, purged of individuality. The architect became an engineer. Beauty became, at best, a happy accident of efficiency.

And then came Le Corbusier — the most influential and most destructive architectural thinker of the twentieth century.

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, aka Le Corbusier, was a Swiss-French ideologue whose certainties would scar cities across the world. He looked at the ancient, layered, humming streets of Paris and saw chaos. He wanted to demolish them. His grotesqye Plan Voisin proposed tearing down virtually the entire north bank of the Seine and replacing it with identical concrete towers arranged in a geometric grid. He wrote, with the calm fanaticism of a man who has never doubted himself: "A house is a machine for living in." And, still more chillingly: "We must kill the street."

These were not British ideas.

They were born in the febrile atmosphere of continental revolution — in Weimar Germany's convulsions, in the wreckage of Habsburg Austria, in a France traumatised by industrial war. They reflected a loss of faith in inherited civilisation so profound it demanded architectural annihilation as therapy.

But they found their way to Britain. Not by force. By invitation.

How Foreign Doctrine Entered British Institutions

The transmission mechanism was institutional. After the Nazis rose to power in 1933 — ironically rejecting modernist architecture as "degenerate" — several prominent Bauhaus figures fled to Britain. Gropius himself worked briefly in London before leaving for Harvard.

Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy spent formative periods in Britain, diffusing their ideas through professional networks and architectural schools.

But the crucial point is this: modernism was not imposed on Britain by refugees. It was embraced, eagerly and voluntarily, by British architects and British institutions. The London County Council Architect's Department — at its peak employing over a thousand architects, responsible for rebuilding vast tracts of London — became a hotbed of modernist enthusiasm.

The Architectural Association, one of the most influential training grounds in the world, shifted its curriculum decisively toward abstraction, functionalism, and the repudiation of tradition. The Royal Institute of British Architects, through its accreditation, awards, and publications, conferred professional legitimacy on modernism and quietly suppressed anyone who dissented.

This stupid political nonsense carries on today.

A generation of young British architects absorbed these continental doctrines as gospel. Alison and Peter Smithson designed Robin Hood Gardens in East London, a brutalist housing estate built on the explicit philosophy of "streets in the sky" — elevated concrete walkways intended to replace the organic social life of the traditional English street. It was a catastrophic failure. The walkways became corridors of isolation and crime. The residents, who had never been consulted about whether they wanted to live in a concrete abstraction, endured the consequences for decades.

Ernő Goldfinger, Hungarian-born and trained in modernist ideology before settling in Britain, designed the repulsive Trellick Tower and even worse Balfron Tower — towering concrete monoliths dropped into London's residential neighbourhoods with the subtlety of artillery shells. Ian Fleming disliked the man so intensely he named a Bond villain after him.

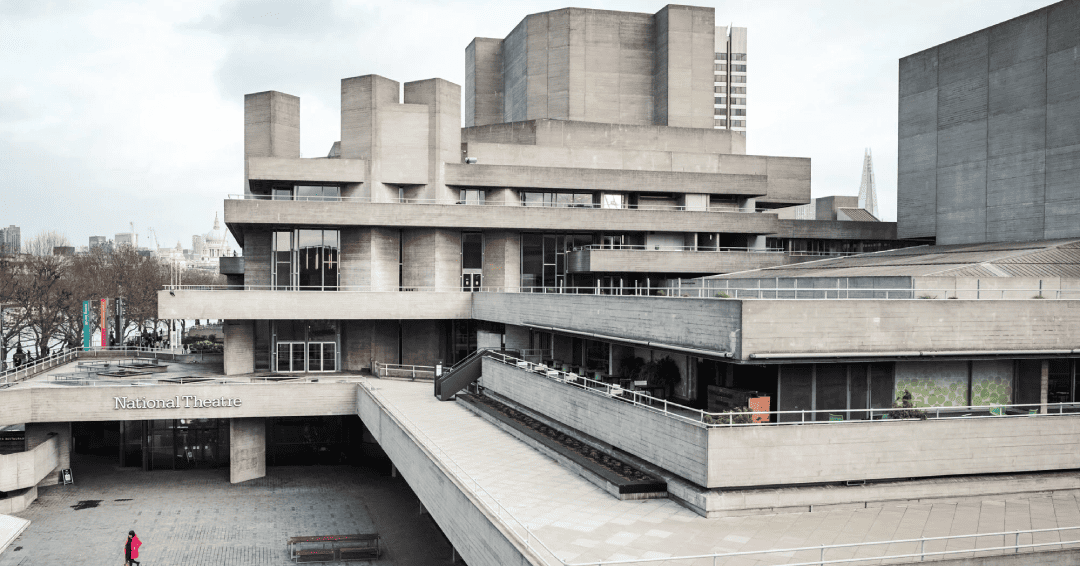

Denys Lasdun gave London the National Theatre — the cover image of this article; a building frequently described as a masterpiece by architects and as a concrete bunker by virtually everyone else. The gap between professional admiration and public dismay was not accidental. It was structural. These architects had been trained to value abstraction over warmth, ideology over intuition, intellectual purity over human experience. They genuinely admired what they built. The trouble was, almost nobody else did.

How the State Seized Architecture

None of this would have mattered much without state power. Architects can hold whatever opinions they please. Ideologues can dream of geometric utopias. But without institutional authority, their visions remain sketches.

What transformed modernist theory into millions of concrete realities was a single piece of legislation: the Town and Country Planning Act 1947.

Introduced by Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town and Country Planning in Clement Attlee's Labour government, this Act did something revolutionary and largely irreversible. It nationalised development rights. After 1947, you could still own land in Britain. But you could no longer build on it without state permission. Every act of construction, every alteration, every change of use required the approval of a planning authority operating under national policy.

Silkin presented the Bill to Parliament with soaring rhetoric. He promised it would create

a new era in the life of this country, an era in which human happiness, beauty, and culture will play a greater part in its social and economic life than they have ever done before.

Beauty. He actually used the word.

The irony is breathtaking. The very legislation intended to protect beauty created the institutional machinery through which beauty was systematically dismantled. Because once planning became a function of bureaucracy, the incentives changed utterly. Architecture ceased to be shaped primarily by the preferences of those who would inhabit it and became shaped instead by the priorities of those who administered it — civil servants, committee members, planning officers, and the architects they hired.

And those administrators, trained in the same modernist orthodoxies, optimised for the things bureaucracies always optimise: measurable outputs. Housing units delivered. Cost per unit. Construction speed. Compliance with regulations.

Beauty is fiendishly difficult to record in a spreadsheet. So it was quietly dropped from the equation. Not by decree. By default.

When Britain Began Building Like a Factory

The numbers are staggering. Between 1949 and 1978, the United Kingdom never built fewer than one hundred thousand council homes in a single year. In 1953, nearly a quarter of a million were completed. By 1966, high-rise blocks accounted for over a quarter of all new housing starts. Council housing peaked at thirty-two per cent of Britain's entire housing stock by 1980.

These were not houses in any traditional sense. They were housing units — the language itself revealing. Units. Products. Outputs of an industrial system designed for throughput, not for living.

The system-building method exemplified the ideology. Prefabricated concrete panels were cast off-site and bolted together on location, like components of a machine. Construction was rapid. Labour requirements were minimal. The panels could be stacked to any height. Speed and scalability were the selling points. Whether anyone would want to live in the result was a question nobody with authority thought to ask.

The catastrophic structural consequences revealed themselves on the morning of 16 May 1968, when a resident on the eighteenth floor of Ronan Point — a twenty-two-storey tower block in Canning Town, East London, opened just two months earlier — struck a match to light her gas stove for a morning cup of tea. The resulting explosion, modest enough to leave her alive, blew out a load-bearing wall. The entire south-east corner of the building collapsed like a house of cards, floor after floor pancaking downward to the ground. Four people died. Seventeen were injured.

The subsequent inquiry found the explosion was small. The building was simply appalling — a system designed for six storeys recklessly extended to twenty-two, with joints so poorly constructed investigators later discovered voids filled with crumpled newspaper and old tin cans where solid concrete should have been.

Ronan Point should have ended the experiment. It did not. The doctrine persisted for another decade. Because the system was optimising administrative metrics, not human experience. It was producing housing units efficiently, regardless of the emotional — or, as Ronan Point proved, the physical — consequences.

When Architects Stopped Living Among Their Work

There is a principle in architecture older than any manifesto: the builder should live among what he builds.

For centuries, this was the default. Craftsmen worked in communities they inhabited. Their reputation depended on the quality of what they produced, because their neighbours walked past it every day. A mason whose stonework crumbled would lose commissions. A builder whose proportions were ugly would lose standing. The feedback loop was immediate, personal, and merciless.

Postwar state architecture severed this loop entirely.

The architects who designed council estates were overwhelmingly middle-class, university-educated, and professionally mobile. They did not live in the towers they designed. The planning officers who approved those designs did not sleep on the walkways they authorised. The committee members who signed off on system-built blocks did not raise children in flats whose walls wept with condensation.

The people who actually occupied these buildings — working-class families rehoused from Victorian terraces or bomb-damaged streets — had no influence whatsoever over the aesthetic outcome. They could accept the housing or refuse it. They could not redesign it. Architecture became something done to the public, not by the public. A vast population was subjected to the aesthetic preferences of a tiny professional class whose members experienced those buildings not as permanent homes but as career achievements — lines on a CV, entries in an awards submission, photographs in a journal.

This separation of consequence from authority is perhaps the single most important structural explanation for why postwar Britain became ugly. The people making the decisions did not bear the consequences. The people bearing the consequences could not influence the decisions. The feedback loop was not merely weakened. It was abolished.

When Beauty Became a Dirty Word

The deepest damage was philosophical. It is difficult, today, to convey the sheer moral fervour with which midcentury modernists rejected traditional beauty. This was not mild aesthetic preference. It was religious conviction dressed in professional jargon.

Ornament was "dishonest." Decoration was "bourgeois." Traditional forms were "reactionary." Beauty, as the English had understood it for a thousand years — proportion, warmth, ornament, harmony with landscape — was reclassified as sentimental illusion. The pitched roof, the decorative cornice, the varied brickwork, the bay window: these were not merely outdated. They were morally suspect. They belonged to the old world — the world of hierarchy, deference, and inherited authority — and the old world, the modernists believed, had failed catastrophically.

Two world wars had broken something in the European intellectual class. The ornate facades of Vienna had not prevented the trenches of Flanders. The baroque splendour of Dresden had not stopped the firebombing. Traditional civilisation, in the eyes of those who shaped postwar architectural doctrine, stood discredited. And so they set about building the opposite: stark, abstract, stripped of every trace of the past. Concrete. Glass. Steel. Repetition. Scale. A world built from scratch, as if history were a disease requiring quarantine.

There is a terrible hubris in this. The assumption — never tested, never subjected to democratic scrutiny — was monumental: the accumulated aesthetic instincts of an entire civilisation were wrong, and a cadre of trained professionals knew better. The English villager who loved her stone cottage was suffering from false consciousness. The Londoner who preferred his Georgian terrace to a concrete slab was clinging to nostalgia. The millions who looked at brutalist towers and felt nothing but cold dread were simply uneducated. Sound familiar?

The professionals knew. The public did not. And the professionals had the planning system.

Living Inside Someone Else's Ideology

The human cost is incalculable because it is largely invisible. Nobody compiles statistics on the depression induced by a stained concrete stairwell. No government report quantifies the anxiety of raising children on an estate designed to eliminate the street — the very institution through which, for centuries, English communities had organised themselves. There is no metric for the slow erosion of pride felt by a family housed in a building whose architect considered beauty a bourgeois indulgence.

But the evidence is everywhere, if you care to look.

Traditional English environments contain variation. Human scale. Warmth of material. Irregularity — the kind of gentle visual complexity the brain finds soothing, because it mirrors the natural world. Brick weathers. Stone ages. Gardens soften edges. A street of terraced houses, no two quite identical, presents the eye with a constantly shifting pattern rich enough to engage but orderly enough to comfort.

Brutalist environments offer the opposite. Repetition at scale. Surfaces designed to resist human imprint. Corridors too wide for intimacy and too narrow for community. Walkways exposed to wind and surveillance but stripped of the organic activity — the shopfronts, the doorsteps, the hedges — through which strangers become neighbours.

The Smithsons' "streets in the sky" were supposed to recreate the vibrancy of traditional street life at altitude. They did nothing of the kind. A concrete walkway on the seventh floor of a tower block is not a street. It has no shops. No front gardens. No children playing under the watchful eyes of adults at nearby windows. It is a corridor — and corridors, as anyone who has walked one late at night will confirm, do not foster community. They foster fear.

Crime flourished on these estates not because their residents were criminal, but because the architecture itself eliminated the mechanisms through which communities self-police. Traditional streets provide what the urbanist Jane Jacobs called "eyes on the street" — the natural surveillance of windows, doorsteps, and passing foot traffic. Tower blocks and megastructures destroyed this entirely. They replaced visibility with anonymity, interaction with isolation, surveillance-by-presence with surveillance-by-camera.

And then the architects and planners blamed the residents.

Ideology Gave Way to Barratt Wasteland

By the early 1980s, the high-modernist tower block had lost its intellectual lustre. Ronan Point's ghost haunted every concrete slab. Public confidence had collapsed. Thatcher's government shifted housing provision toward the private sector.

But what replaced state brutalism was not beauty. It was a different species of ugliness — less aggressive, perhaps, but no less dispiriting.

Private developers, operating within the planning framework the state had created, began producing vast estates of standardised homes. These were the Barratt homes and their imitators — row upon row of near-identical boxes clad in thin brick or rendered blockwork, arranged in meandering cul-de-sacs designed not for community but for ease of planning approval. The proportions were cramped. The materials were cheap. The layouts were interchangeable from Basingstoke to Barnsley.

This was not ideological brutalism. It was commercial apathy. The developer's objective was not to reshape society. It was to maximise profit within regulatory constraints. Beauty was not rejected on philosophical grounds. It was simply not profitable enough to pursue. Varied rooflines cost more than uniform ones. Quality brick cost more than render over blockwork. Ornamental detailing required skilled labour no one wished to train or employ.

The planning system, meanwhile, continued to optimise the same variables it had always optimised: density, land use, regulatory compliance. Beauty remained unmeasured, and therefore unoptimised. The result was a landscape of staggering monotony — neither offensively brutal nor remotely inspiring. Just empty. Developments designed to be approved, not admired. Built to survive the planning process, not the centuries.

England's suburbs filled with houses nobody would ever write a poem about. Nobody would paint them. Nobody would photograph them for pleasure. They were not architecture. They were units — the same word, the same philosophy, the same indifference — assembled by different hands.

Architecture as Severed Inheritance

Behind the concrete and the cladding lies a wound deeper than aesthetics. The English relationship with landscape is profoundly moral. This is not sentimentality. It is a civilisational constant reaching back through and past Constable and Turner, through and beyond Wordsworth and Ruskin, through the medieval understanding of the parish as both spiritual and physical territory. The English do not merely inhabit their landscape. They read it. They interpret its contours as expressions of continuity, of rootedness, of belonging to something larger than the individual lifespan.

A church spire rising above a village is not decorative. It is a statement about the relationship between the human and the eternal, rendered in stone and visible from miles away. A Georgian square is not merely pleasant. It is an argument — in sandstone and proportion — for civic order, for the possibility of public beauty, for the idea of a common life enriched by shared surroundings.

When the modernists declared war on tradition, they did not merely change architectural fashion. They severed a connection between the English people and their built inheritance — a connection centuries in the making, woven so deeply into the national character it had become invisible until it was destroyed.

What replaced it was not a new tradition. It was the absence of tradition. A landscape of administrative outputs. An environment shaped not by love but by logistics. Buildings designed to be delivered, not to endure. Structures intended to solve problems on paper but incapable of nourishing the spirit in person.

The philosopher Roger Scruton spent decades arguing what millions of ordinary Britons felt in their bones: beauty matters. It is not a luxury. It is not a bourgeois indulgence. It is a fundamental human need — as basic as warmth, as essential as shelter, as necessary to the health of a civilisation as clean water is to the health of a body. Deny it long enough and something in the collective psyche begins to wither.

Look at Britain's towns. Drive through its ring-road hinterlands, its retail parks, its endless suburbs of developer housing distinguished from one another only by postcode. And ask yourself: does this landscape look like it was built by people who loved it?

Or does it look like it was built by people who were filling in forms?

How You Build a Dystopia Without Meaning To

Here is the terrible paradox at the heart of this story. Nobody planned to make Britain ugly. The planners planned to make it better. The architects believed — many of them sincerely, passionately, with the fervour of converts — they were improving civilisation. The civil servants were solving a housing crisis of genuine and desperate urgency. The politicians were delivering on electoral promises. Every actor in the system was, within their own frame of reference, doing the right thing.

And yet the cumulative result was a catastrophe.

This is the technocrat's trap. It is the trap sprung whenever a society hands complex human problems to administrative systems designed to optimise measurable outputs. Each individual decision within the system appears rational. Concrete is cheaper than stone: rational. Uniform designs reduce planning complexity: rational. High-rise towers maximise density: rational. Prefabricated panels accelerate construction: rational.

But the sum of a thousand rational decisions, each blind to what cannot be quantified, can produce an outcome profoundly irrational — an environment technically adequate but spiritually barren. No single decision creates a dystopia. Dystopia emerges from cumulative optimisation of the wrong variables.

The system measured housing units. It measured cost. It measured speed. It never measured whether a child growing up on the fourteenth floor of a tower block would feel the kind of quiet pride in her surroundings from which larger ambitions grow. It never measured whether an elderly man relocated from a terraced street to a concrete walkway would lose the casual daily contact with neighbours upon which his mental health depended. It never measured beauty, because beauty resists measurement.

And what a system cannot measure, it cannot optimise. And what it cannot optimise, it ignores. And what it ignores, it destroys.

Our Civilisation's Unfinished Business

The buildings are still there. Drive through any major English city and they confront you — the slabs, the towers, the windswept plazas, the stained concrete facades, the identikit estates stretching to the horizon. They are the physical residue of an ideology almost nobody now defends but almost nobody has troubled to reverse. They stand as monuments to a half-century of institutional arrogance — the period when a professional class presumed to know better than a civilisation, and a planning system gave them the power to prove it.

And they will continue standing, shaping lives, pressing down on spirits, until someone — until enough of us — decide they are intolerable.

Not merely unsightly. Not just regrettable. Intolerable.

Because the central question this history forces upon us is not architectural. It is political: who decides what Britain looks like? For centuries, the answer was: the people who lived there, building slowly, inheriting wisely, adapting carefully. After 1947, the answer became: the state, its planners, its architects, its committees. The people who bore the consequences had no meaningful voice in the outcome.

This must end. Not with another quango. Not with a royal commission producing a report to gather dust in a Whitehall filing cabinet. Those instruments are the disease, not the cure. The very administrative machinery through which beauty was destroyed cannot be trusted to restore it.

What is needed is simpler and more radical: a civilisational decision to treat beauty as infrastructure. Not as luxury. Not as subjective taste to be debated endlessly in planning inquiries. As infrastructure — as essential to the health of a community as drainage, as indispensable to the flourishing of a nation as roads.

Planning law can be rewritten to make beauty a statutory consideration — not vague aspiration buried in supplementary guidance, but a binding criterion against which every major development is measured. Architectural education can be reformed to restore the teaching of proportion, craft, and material permanence alongside whatever contemporary methods the profession values. The feedback loop between builder and inhabitant can be restored by giving local populations genuine power — not consultative theatre, but real authority — over the aesthetic character of their surroundings.

Demolish it all.

And the buildings themselves — the concrete failures, the system-built towers reaching the end of their engineered lifespans, the brutalist monuments whose admirers are invariably people who do not live in them — can be decommissioned. Not in a frenzy of demolition, but through the steady, patient, generational work of replacement guided by a single recovered principle: what we build must be worthy of permanence.

King Charles understood this before most. At the RIBA's one hundred and fiftieth anniversary in 1984, he described a proposed modernist extension to the National Gallery as "a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend." The architectural establishment howled. They called him backward, naive, an enemy of progress. He was none of those things. He was an Englishman — with an Englishman's instinct — expressing what millions felt but lacked the platform to say: this is not good enough. We deserve better. Our country deserves better.

This organisation – RIBA – is a disgrace. It's been a disgrace since the beginning. Demolish it.

Britain was not always ugly. It became ugly through a specific sequence of choices — ideological, legislative, institutional, professional — made by a specific class of people over a specific period of time. Those choices can be unmade. The ideology can be rejected. The institutions can be reformed. The doctrine — the wretched, arrogant, continental doctrine that beauty is dishonest and ornament is crime and a house is a machine — can be thrown on the same intellectual scrapheap as every other failed utopian scheme of the twentieth century.

The English landscape is not a spreadsheet to be optimised. It is not an administrative problem to be solved. It is a moral inheritance — the physical expression of a civilisation's accumulated care — and it belongs to the people who live within it. Every generation receives it as a trust and passes it on, enriched or diminished, to the next.

For fifty years, we diminished it. We allowed ideologues to disfigure it, bureaucrats to neglect it, developers to cheapen it. We permitted a planning system built for administrative efficiency to extinguish the one quality no administrative system can produce: beauty.

It is time — long past time — to take it back.

Let's demolish it all. All the buildings which aren't English. Why not? It's out country. We say what gets to live here.