How Sudan's Christians Became Targets in Africa's Deadliest War

Whilst the world looks away, again, tens of thousands lie dead in Sudan's killing fields. The blood is visible from space. Churches burn. Christians flee. And Britain, once colonial master, now stands silent before the horror it helped create. The brutality of Sudan's civil war is hidden from view.

The satellite images show what the communications blackout conceals. Across western Sudan, dark stains spread across the desert sand—pools of blood large enough to see from orbit. Near the city of el-Fasher, objects consistent with human bodies lie in clusters. Some experts estimate tens of thousands have been killed in recent weeks alone. The speed and intensity of the slaughter draws comparisons to the opening hours of the Rwandan genocide.

Most of the world has never heard of what is happening in Sudan. Whilst Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines, Africa's largest country by area bleeds to death in near silence. Since April 2023, Sudan has descended into what the United Nations calls the worst humanitarian catastrophe on earth.

Estimates of the death toll vary wildly—the UN suggests 40,000, but models based on satellite imagery and mortality data indicate the true figure could exceed 150,000. Some 14 million people have fled their homes. Famine stalks entire regions. And buried within this broader catastrophe lies a targeted campaign of violence against one of the region's most vulnerable minorities: Sudan's Christians.

A British Inheritance of Division

To understand how Sudan arrived at this moment requires reaching back more than a century, to when British imperial administrators sat in Cairo and Khartoum drawing lines on maps. The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, established in 1899, was colonial administration in its most cynical form—Britain exercised effective control whilst maintaining the legal fiction of joint sovereignty with Egypt. The arrangement suited London perfectly: strategic dominance over the Nile Valley without the inconvenience of direct colonial responsibility.

British officials approached Sudan with the instincts of empire-builders everywhere: divide and rule. They segregated the country into distinct spheres, developing the Arab-Muslim north whilst leaving the African Christian and animist south deliberately isolated. Investment flowed to northern infrastructure—railways, ports, irrigation schemes. The 1922 Closed District Ordinances formalised this segregation, requiring special permits for northerners to travel south and restricting trade between regions. The British established separate administrative systems, different educational policies, even different currencies in various zones.

This was not accidental neglect but calculated policy. British administrators, still nursing memories of the Mahdist uprising, feared the spread of Arab-Islamic influence southward. They encouraged Christian missionary activity in the south whilst suppressing it in the north, creating a religious fault line where none had existed so starkly before.

Meanwhile, northern elites received British education and administrative positions, preparing them to inherit power. Southern regions received little state investment and were delegated to missionaries for education—groups whose primary goal was proselytisation, not academic development.

When Sudan gained independence on 1 January 1956, it inherited a state fractured along lines the British had spent half a century reinforcing.

The north, wealthier and politically organised, assumed control. The south, deliberately underdeveloped and marginalised, found itself ruled by the very people British policy had elevated above them. Within months, civil war erupted. The pattern would repeat across decades: northern Arab-Muslim governments seeking to impose Islamic law and cultural dominance; southern and peripheral populations resisting.

More than 2.5 million Sudanese have been killed in various conflicts since independence—a death toll exceeding the Rwandan genocide several times over, though garnering a fraction of the international attention.

The First Genocide: Darfur's Killing Fields

The Darfur crisis of 2003 to 2005 served as prologue to today's horrors. When rebel groups attacked a government post in western Darfur, demanding the Khartoum regime provide basic services to the neglected region, President Omar al-Bashir responded not with negotiation but annihilation.

Al-Bashir, a career military officer who had seized power in a 1989 coup, unleashed a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing. Government forces and Arab militias known as the Janjaweed—"devils on horseback"—swept through Darfur's African villages. Russian-made Antonov bombers pummelled settlements from above. Militia fighters followed, killing men and boys, raping women and girls, burning homes, poisoning wells. Racial epithets accompanied the violence: victims were called "slaves" and "blacks," their African ethnicity marked for destruction.

The Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa peoples bore the brunt. Witnesses described militiamen separating families, executing males regardless of age, subjecting women to systematic sexual violence designed to destroy communities from within. Human Rights Watch documented cases of infants bludgeoned to death. Survivors spoke of watching their villages burn whilst gunmen prevented escape. Between 2003 and 2008, approximately 300,000 civilians died. Another 2.7 million were displaced, many fleeing to squalid camps in neighbouring Chad.

In September 2004, US Secretary of State Colin Powell became the first major world leader to state plainly what was happening: genocide. The International Criminal Court eventually indicted al-Bashir on charges of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity—the first sitting head of state so charged. Yet he remained in power another fifteen years, travelling freely to numerous African capitals whose governments ignored their obligation to arrest him.

Christians suffered alongside Muslims during the Darfur genocide, though the violence was primarily ethnic rather than religious. What matters for understanding today's crisis is this: the Janjaweed militias, those devils on horseback, never truly dissolved. In 2013, al-Bashir formalised them as the Rapid Support Forces. The RSF became a powerful paramilitary, operating alongside the regular army, conducting counter-insurgency operations and border patrols. Its commander, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo—known universally as Hemedti—cultivated foreign relationships and enriched himself through gold mining and arms trafficking.

The genocidaires of Darfur became an institutional force within the Sudanese state, waiting for their next opportunity.

The War Of Two Generals Nobody's Watching

In April 2019, a popular uprising finally toppled al-Bashir. Sudanese citizens, particularly women and young people, took to the streets demanding democracy and civilian rule. Initially, hope flourished. A transitional government emerged, promising religious freedom, equal rights, investigations into past atrocities. Sudan's Christians, who comprise perhaps 5% of the population concentrated in the Nuba Mountains, South Kordofan, Blue Nile State, and major cities, dared to imagine a future of tolerance.

The dream proved short-lived. In October 2021, the military seized power again. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sudanese Armed Forces, and Hemedti, commanding the RSF, jointly overthrew the civilian government. They ruled together uneasily until, in April 2023, their alliance shattered over plans to integrate the RSF into the regular military. What began as a power struggle between two generals has metastasised into catastrophic civil war.

Both sides are ruthless. Both have committed atrocities. Neither cares particularly about the civilians caught between them. The Sudanese Armed Forces bomb indiscriminately from the air, using Russian-supplied aircraft to pound residential areas. The RSF operates more like a guerrilla force, employing genocidal tactics perfected in Darfur. But one pattern has emerged with unmistakable clarity: Sudan's Christians find themselves targeted by both factions whilst protected by neither.

Churches in the Crossfire

More than 165 churches have closed since war erupted. Some were commandeered for military use, with worshippers forced out or killed to make room for soldiers. Others became targets of deliberate attacks. Bombs fall on church compounds with grim regularity, killing those sheltering inside—often women and children seeking refuge from the violence.

On 13 May 2023, RSF fighters stormed Mar Girgis Coptic Church in Omdurman. They shot four men including the priest and stabbed another. Whilst assaulting worshippers, the attackers hurled insults: "sons of dogs and infidels." They demanded conversion to Islam, holding a dagger to the priest's back.

Two days later, RSF soldiers attacked the Coptic church complex in Bahri, north of Khartoum. Five clergy were shot. Everyone present was threatened and abused. The Bishop of Khartoum and South Sudan was forcibly evacuated from the Virgin Mary Coptic Orthodox Church.

The pattern continued as the RSF seized territory. When they captured Gezira State in December 2023, their first assault targeted a Coptic monastery in Wad Madani, now used as a military base. The Evangelical Church in that city was set afire and partially destroyed—the second such arson attack in a month. RSF commanders later released propaganda videos showing themselves forcibly hugging priests and distributing money, a grotesque performance meant to suggest benevolent treatment.

The violence is not random. Christian leaders report their churches are specifically targeted for seizure and destruction. One priest from northern Sudan described the situation starkly:

We are being devoured by both sides. There is genocide—of any group standing in their way. There is no moral context anymore.

This is not primarily a religious war in the sense of jihadist ideology driving the conflict. Both the SAF and RSF are fighting over control of Sudan's considerable resources—gold deposits in the west, oil in border regions, strategic ports on the Red Sea. Greed, not theology, animates the combatants.

Yet Christianity in Sudan has become what one aid worker termed "a secondary target." Churches occupy valuable real estate. Christian communities often lack the tribal or political connections offering protection. Converting or displacing them serves both military and ideological purposes for forces steeped in Islamist ideology inherited from the al-Bashir era.

The Sudanese Armed Forces, though less overtly hostile to Christians than the RSF, include significant Islamist elements. Al-Burhan has reinstated former members of al-Bashir's National Congress Party, the Islamist movement governing Sudan from 1989 to 2019. These figures view Christianity with suspicion at best, hostility at worst.

Meanwhile, the RSF—despite evolving from Janjaweed militias less ideologically motivated than tribally Arab—has demonstrated particular viciousness towards Christian communities during its territorial advances.

The Nuba Mountains: Christianity Under Siege

Christians in the Nuba Mountains face exceptional peril. This resource-rich region, retained by Khartoum when South Sudan gained independence in 2011, hosts significant Christian populations among the Nuba people. Successive Sudanese governments have conducted what many describe as ethnic cleansing operations there, viewing the Nuba as obstacles to resource extraction and Arab-Islamic dominance.

When war erupted in 2023, bombs fell on the Nuba Mountains for the first time since 2016. SAF fighter jets targeted civilian areas just as new relief shelters were being completed. Hundreds of thousands of war-weary Christians—many genocide survivors from previous conflicts—faced renewed terror. They began fleeing southward again, joining the exodus of 12 million internally displaced persons scattered across Sudan and neighbouring countries.

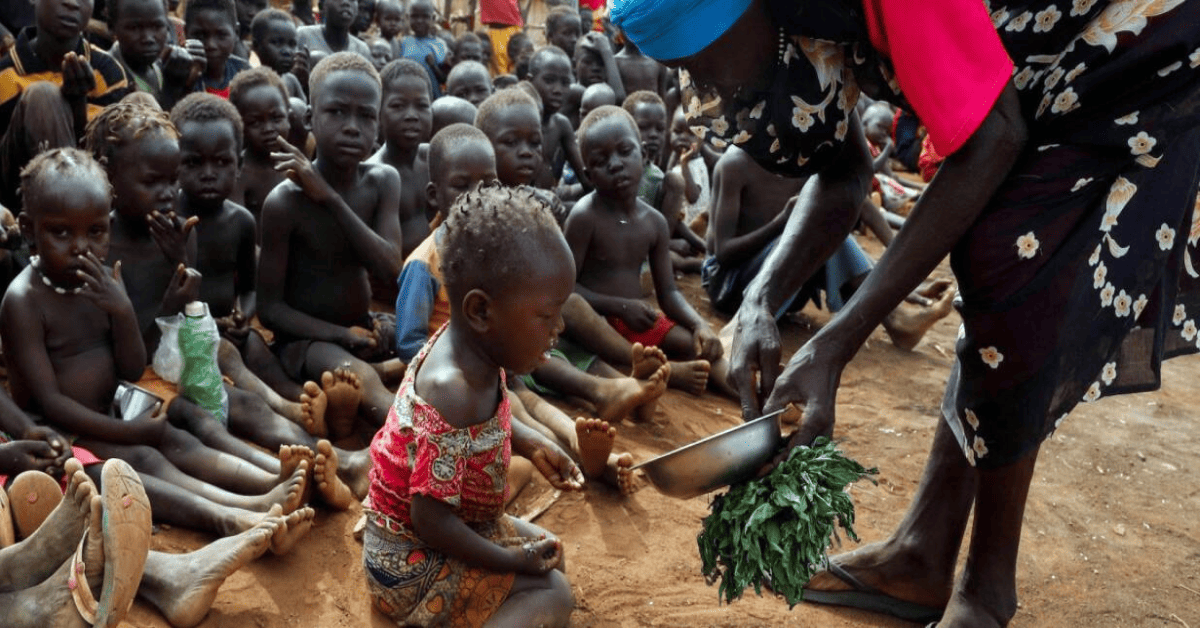

In displacement camps, discrimination follows Christian refugees. Local communities often refuse aid to Christians, leaving them to face famine conditions without the support networks available to Muslim populations. Women and girls suffer particular torment: the RSF and allied militias have used sexual violence as a weapon of war. UN investigators documented more than 400 women seeking medical treatment for sexual assault between April 2023 and July 2024—the true number is certainly far higher, as stigma prevents many from reporting.

Girls as young as thirteen have been kidnapped for sexual slavery. RSF soldiers reportedly use racial and religious slurs whilst assaulting non-Arab, non-Muslim victims. One Christian woman in a displacement camp in southern Sudan spoke through tears:

There are many diseases, we fall sick, we need medicine to cure us and our children. We have so many challenges and pray God will hear and see my tears due to this situation and war.

The Masalit Genocide

In January 2025, the United States formally determined the RSF and its allied militias are committing genocide in Sudan, specifically targeting the Masalit ethnic group in West Darfur. Secretary of State Antony Blinken cited systematic murder of men and boys, widespread sexual violence against women and girls, and deliberate obstruction of humanitarian assistance.

Whilst the Masalit are primarily Muslim, Christians often live amongst them and suffer the same atrocities. The genocidal attacks follow a familiar template: RSF forces encircle villages, separate males from females, execute the men and boys, rape the women and girls, then burn everything.

Between ten and fifteen thousand people were killed in West Darfur in 2023 alone through such operations. In November of that year, RSF forces and allies killed more than 800 people during a multi-day rampage in Ardamata.

The violence has only intensified. In October 2025, el-Fasher—the last Sudanese Armed Forces stronghold in Darfur—fell after an eighteen-month siege. The RSF immediately began what they termed a "combing operation." Eyewitnesses who escaped describe execution squads at roadblocks:

They would ask a man to run. Once you start running, they shoot you.

Sudan Doctors Network reported at least 1,500 people killed in the first three days after el-Fasher's fall, calling it "a true genocide." The Sudanese government claimed 2,000 dead. Yale University's Humanitarian Research Lab, analysing satellite imagery, documented objects consistent with human bodies and pools of blood across the city and surrounding areas. They estimated the 250,000 remaining civilians had been killed, displaced, or driven into hiding. Some analysts suggest tens of thousands died in the massacre's opening weeks—a scale of killing unprecedented in recent conflicts.

Christians in el-Fasher and across Darfur face these horrors alongside their Muslim neighbours. The broader genocide creates conditions where all non-Arab populations become targets, and Christians—already marginalised, already vulnerable—suffer disproportionately.

The World's Complicity Through Silence, Again

Foreign powers bear responsibility for this catastrophe. The United Arab Emirates has extensively armed the RSF, providing sophisticated weaponry and funding operations. Human Rights Watch documented UAE supply lines running through ports and airports, violating international arms embargoes. These weapons enable massacres. This money pays the salaries of genocidaires.

When the International Court of Justice began hearing Sudan's case against the UAE for alleged violations of the Genocide Convention, the RSF responded by launching fresh attacks on displacement camps—a brutal demonstration of contempt for international law.

Egypt and Iran supply the Sudanese Armed Forces with weapons and support. Russia provides aircraft and diplomatic cover. China floods both sides with recently manufactured small arms, fuelling the killing whilst officially maintaining neutrality. These external actors pursue their interests—access to gold, control of Red Sea ports, ideological influence—without regard for Sudanese lives.

Britain's role is particularly shameful.

Having created many of the divisions now expressing themselves in genocidal violence, successive British governments have offered tepid statements and minimal aid. There are no serious sanctions against genocide perpetrators. No arms embargo enforcement. No sustained diplomatic pressure. British officials occasionally express concern at the UN, then return to business as usual. The colonial power that spent decades deliberately fracturing Sudanese society now watches that society tear itself apart with barely a murmur of conscience.

Western media coverage remains sporadic at best. When war erupted in April 2023, it merited brief attention before fading from front pages. The fall of el-Fasher in October 2025, with its tens of thousands dead, received less coverage than celebrity scandals. Sudan's Christians suffer in near-total obscurity, their persecution invisible to populations who might otherwise demand action.

What Christians Are Asking For

Christian leaders in Sudan make simple appeals. They ask the international community to pressure combatants to stop targeting churches and civilians. They request humanitarian corridors to deliver food and medicine to displacement camps where Christian populations face deliberate discrimination. They plead for investigations and accountability—the International Criminal Court's fact-finding mission remains critically underfunded, unable to properly document ongoing atrocities.

One church leader's plea carries particular urgency:

Please tell leaders of churches and anyone with a Christian conscience to put pressure on belligerents, even on those who keep supplying them with arms and bombs. Try sanctions. Try something. Anything. Just stop the dying.

Yet the dying continues. Sudan faces famine across multiple regions. The Global Hunger Monitor issued alerts for five areas. At least 25 million people suffer severe food insecurity. Nearly four million children are acutely malnourished, with more than 770,000 at imminent risk of death. In refugee camps in Chad, ten children die from malnutrition every week. Cholera epidemics rage through displacement centres lacking clean water and sanitation.

Both the SAF and RSF deliberately weaponise starvation, blocking humanitarian aid to areas controlled by opponents. Food convoys are turned back at checkpoints. The Sudanese government barred all international and UN aid workers from Darfur in October 2024, claiming they violated "national sovereignty." At least twenty-two aid workers have been killed. The few humanitarian organisations still operating face impossible conditions.

Britain's Reckoning: Here We Are Again

British Christians should feel particular responsibility. Their government's colonial policies created the structural conditions enabling today's genocide. The segregation of north and south, the deliberate underdevelopment of Christian and animist regions, the elevation of Arab-Muslim elites, the failure to build unified national institutions—all this flows from decisions made in London and implemented in Khartoum.

When Britain granted Sudan independence in 1956, it left behind a state designed to fail. Southern regions had been isolated for decades, denied investment and education, taught to fear and resent northern dominance. Northern elites, educated in British systems and accustomed to power, assumed they would inherit control over resources and governance. No meaningful preparation for democratic self-government occurred. No effort to heal divides or build shared national identity preceded independence. Britain simply walked away, mission accomplished, leaving Sudanese to manage the wreckage.

The subsequent decades of civil war, genocide, and authoritarian rule cannot be blamed entirely on British colonialism—Sudanese actors made choices producing these outcomes. Yet the original sin remains Britain's. The structures of oppression, the fault lines of conflict, the template for marginalising peripheral Christian and animist populations—these were British innovations, implemented methodically across fifty-seven years of colonial rule.

Today's genocide against Christians in Sudan represents the culmination of that colonial legacy. When the British segregated south from north, when they denied investment to Christian regions, when they handed power to Arab-Muslim elites whilst abandoning minority populations, they set in motion dynamics now expressing themselves in church burnings and targeted killings. British policymakers understood they were creating divisions. That was the point. Divided populations cannot unite against colonial masters.

We Need To Act, Now

The international community must impose comprehensive sanctions on both warring parties and their foreign backers. The UAE, Egypt, Iran, Russia, and China should face consequences for arming genocide. Arms embargoes must be enforced, not merely declared. Financial sanctions should target RSF gold-smuggling operations and the networks enabling weapons purchases.

The UN Security Council must authorise humanitarian intervention to protect civilians and ensure aid delivery. Safe corridors should be established for Christian and other minority populations to escape violence. Displacement camps require adequate funding for food, medicine, and sanitation. The International Criminal Court needs resources to document crimes and prepare prosecutions.

Churches across Britain and the West should mobilise their congregations. Write to MPs demanding action. Fund Christian aid organisations working in Sudan and neighbouring countries. Publicise this forgotten genocide—most people remain simply unaware it is happening. Pressure governments to act. Religious freedom is supposedly a core Western value; defending it requires more than rhetoric.

Most fundamentally, Sudan needs peace.

Not the false peace of authoritarian stability under al-Bashir, but genuine reconciliation addressing decades of marginalisation and violence. This requires civilian government representing Sudan's diversity—Arab and African, Muslim and Christian, north and south. It requires acknowledgement of past crimes and commitment to accountability. It requires economic development reaching all regions, not just Khartoum and privileged areas.

Such transformation seems impossibly distant whilst generals fight over gold mines and Christians flee burning churches. Yet without fundamental change, cycles of violence will repeat. The Janjaweed became the RSF; the RSF will evolve into something else. Genocidal forces, once unleashed, rarely dissolve entirely. They metastasise, finding new targets, adapting tactics, waiting for opportunities.

Blood Visible from Space

Satellite imagery doesn't lie. The blood spreading across Sudan's sands is real. The bodies lying in clusters near el-Fasher existed as people—farmers, teachers, mothers, children—before becoming objects viewed from orbit. Among them were Christians whose only crime was worshipping in the wrong place at the wrong time, belonging to communities marked for destruction by forces pursuing power and profit.

Their suffering deserves more than silence. It demands witness, action, accountability. British Christians, in particular, cannot look away. Our government's colonial policies helped create this catastrophe. Our current government's inaction enables its continuation. We bear responsibility to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves, to pressure leaders who prefer convenient ignorance, to remember those the world has forgotten.

The Sudanese Christians asking simply for church leaders to notice their suffering, to pressure combatants, to try sanctions, to try something, to try anything—they deserve answers. Not empty words about concern and monitoring. Not another UN resolution filed and forgotten. Real action: weapons embargoes enforced, humanitarian aid delivered, war criminals sanctioned, refugees protected.

Otherwise, the satellites will continue recording what our consciences refuse to see: blood spreading across the desert, visible from space, whilst the world looks away.