How Tony Blair Perverted British Charity Into NGO Activism

Britain took 400 years to build a charity sector focused on genuine need and rooted in local community. Tony Blair dismantled it in five years by quietly defining what it meant, and replaced it with something unrecognisable: a politicised US-style NGO fundraising network.

Your grandmother understood what charity meant. She knew it in her bones, the way you know things passed down through centuries of practice. Charity was the church fund for widows. The trust deed leaving money for apprenticeships. The local school endowed by a wool merchant in 1687. Charity was helping the poor, teaching the ignorant, and serving God. These purposes were so fundamental to English life they'd been written into law in 1601—under Elizabeth I—and nobody had much troubled them since.

If you'd told her that by 2025, registered charities would be referring each other to the police over statements about Gaza, she would have thought you mad. If you'd explained how organisations could raise tax-deductible donations through a "charitable trust" and then funnel the money into a private limited company doing political campaigning, she would have asked when Parliament had lost its mind.

The answer is 2006. Tony Blair's government. And you probably never heard about it.

Four Centuries Of Settled Law

British charity law was ancient, eccentric, and deeply conservative. The legal definition came from the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 and a Victorian court case called Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v. Pemsel (1891) which established four categories:

- Relief of poverty

- Advancement of education

- Advancement of religion, and

- Other purposes beneficial to the community.

Note what's missing.

No "human rights." No "equality and diversity." No "conflict resolution."

These modern obsessions simply didn't qualify. If you wanted to run a political advocacy group—perfectly legitimate—you formed a society, a club, a company. You couldn't dress it up as charity and claim tax advantages. The line between charity and politics was bright and clear.

This wasn't some accident of history. It was a deliberate firewall built into the British constitution. Charity belonged to civil society, free from the state. Politics belonged to Parliament and the rough business of democratic contestation. Mixing the two corrupted both.

The Charity Commission, established in 1853, existed to police this boundary. Charity money came with restrictions. You held it in trust for specific purposes. You couldn't divert it to private benefit. You certainly couldn't use it for party politics or controversial campaigning. The Commission's job was to ensure every pound raised for charitable purposes went to charitable purposes—the real ones, not whatever some activists had decided to call charitable this week.

This system produced a charity sector focused on what charities should focus on: hospitals, schools, almshouses, rescue missions, medical research, disaster relief. Local groups helping local people. When someone rattled a tin on the high street, you knew where the money was going.

Enter New Labour's "Modernisation"

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair had other ideas.

In July 2001, fresh from his second landslide election victory, Blair ordered the Strategy Unit—part of the Cabinet Office—to review the entire voluntary sector. The resulting report, delivered in September 2002 under the title "Private Action, Public Benefit," reads today like a revolutionary manifesto smuggled into Whitehall jargon.

The report proposed to "modernise" charity law.

Which meant, in practice, dynamiting four centuries of settled understanding and replacing it with something completely different. The rationale was pure New Labour: charities were too "traditional," too focused on "service delivery," not "entrepreneurial" enough. They needed to be "empowered" to "advocate effectively" and "influence policy." They should be "partners" with government, embedded in "civil renewal" and "community cohesion" programmes.

If this language makes your skin crawl, trust your instincts. What Blair's people wanted—what they built—was an American-style NGO network.

Not charities in any meaningful sense, but professional advocacy organisations, policy shops, campaigning groups, all dressed up in charitable clothing and funded by tax-advantaged donations.

Rewriting The Definition Of Charity

The Charities Act 2006 created a statutory definition of "charitable purposes" for the first time in English history. Out went the Elizabethan categories, understood through centuries of case law. In came a modern list of thirteen purposes, drafted by civil servants and including several entirely novel concepts.

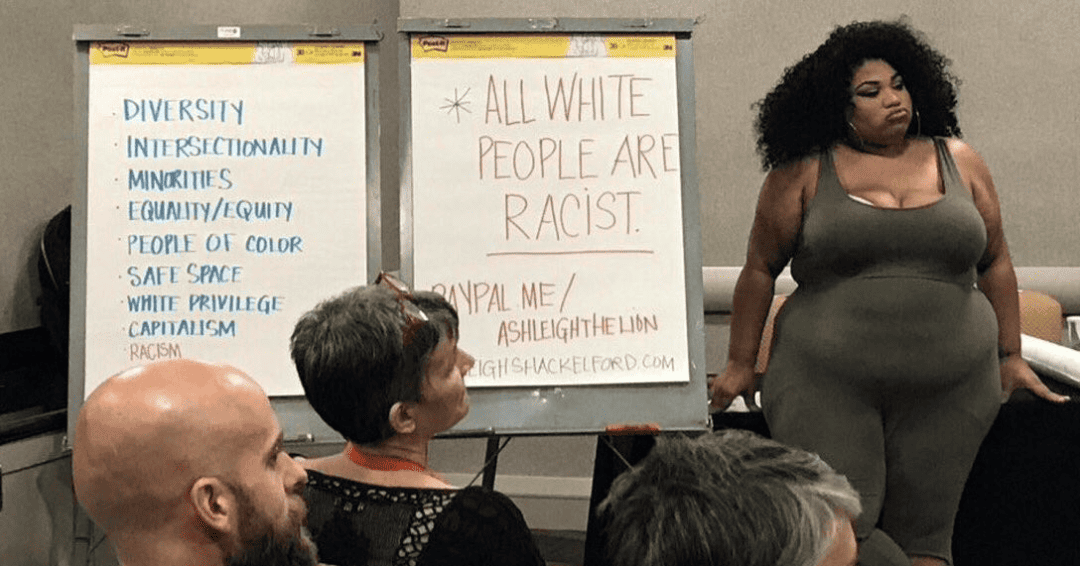

"Advancement of human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation or the promotion of religious or racial harmony or equality and diversity" became, at a stroke of Blair's pen, a charitable purpose.

Read it again. "Human rights" and "equality and diversity"—the contested political obsessions of progressive activism—were now legally equivalent to feeding the hungry and housing the homeless.

Do you see what happened? The Act didn't just expand charity law at the margins. It fundamentally redefined what charity meant. Activities once considered straightforwardly political—lobbying for changes to discrimination law, campaigning on identity issues, advocacy on international conflicts—could now be packaged as charitable work. Apply for registration. Collect tax-deductible donations. Enjoy Gift Aid.

Historically, the promotion of human rights was often difficult to register as a charity because the courts, in cases like McGovern v Attorney General (1981), viewed activities aimed at changing the law or government policy (political purposes) as non-charitable.

The Charity Commission, which for 150 years had jealously guarded the boundary between charity and politics, rolled over. Their guidance, published after the Act, noted primly:

The promotion of human rights is a relatively new charitable purpose...only recognised in its own right by the Charity Commission in 2002.

Only recognised in 2002. After four centuries of charity law. Because Tony Blair decided it should be.

How To Fund Politics Through Charity

But the Act did something else, more insidious and less noticed. It created new legal structures—the Charitable Incorporated Organisation—and clarified how charities could operate trading subsidiaries and connected companies. This sounds technical. It's not. It's the skeleton key to understanding how modern British "charity" actually works.

You set up two entities: a registered charity (usually a trust) and a private limited company.

The charity has charitable purposes, raises donations, claims Gift Aid, and looks respectable. The company does the actual work—campaigning, lobbying, communications, "research"—without the tedious restrictions charity law imposes on political activity.

The charity then makes "grants" to the company to fund its work. Provided the trustees write it up correctly—charitable objects, public benefit, monitoring arrangements—this is entirely legal.

Money flows from charitable donations into political campaigns. The donor thinks he's supporting a charity. He's actually funding an activist organisation structured as a private company.

Take the Islamic Human Rights Commission Trust. In October 2025, the Charity Commission opened a statutory inquiry into the organisation—specifically about its funding of a non-charitable company and concerns over inflammatory statements made at an event the charity supported. The Commission's announcement was blunt: the inquiry would examine "the unclear relationship between the charity and non-charitable company" and its impact on "public trust and confidence in the charity and charities more widely."

This wasn't the Commission's first intervention. In March 2023, they'd issued an Official Warning about how the charity managed its relationship with the non-charitable company. The warning didn't work. The structure persisted. By 2025, the regulator felt compelled to launch a full statutory inquiry.

The Islamic Human Rights Commission Trust is registered under the post-2006 framework with purposes including—you guessed it—"advancement of human rights." That phrase, inserted into charity law in 2006, made the entire structure possible.

Before Blair's reforms, you couldn't have registered a "human rights" charity in the first place. Now you can register one, fund a separate company through it, and the Charity Commission spends its time trying to untangle whether the arrangement breaches the rules they themselves approved.

And this structure is everywhere. UK Lawyers for Israel runs a charitable trust alongside its main advocacy organisation. Dozens of campaign groups operate the same model. All perfectly legal under the framework Parliament created in 2006.

Importing The American NGO Machine

The truly brilliant bit—from Blair's perspective—was the timing and the politics. In 2001, the Labour Party was stuck. The traditional left, rooted in trade unions and Fabian socialism, was dying. The unions were weak. The membership was aging. The Militant Tendency had been purged. Labour needed a new base.

American Democrats had solved this problem decades earlier.

They'd built a network of advocacy groups, think tanks, campaigning organisations, and "community organising" outfits—nominally independent of the party, structured as tax-exempt non-profits (501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) entities), funded by wealthy donors and foundations. These groups did the work political parties couldn't do: continuous campaigning, policy development, identity mobilisation, media operations. They weren't the party. They were better than the party. They were the infrastructure.

Britain had nothing like this. The left had the unions and some single-issue campaigns. The right had a few think tanks and the voluntary instinct of Conservative associations. But nobody had the American model: the permanent, professional, tax-advantaged advocacy network.

Blair imported it. The Charities Act 2006 was the enabling legislation.

By redefining charity to include human rights, equality, diversity, and conflict resolution, he created space for hundreds of organisations to claim charitable status while doing political work. By clarifying how charities could fund non-charitable companies, he provided the structure for sophisticated operations to raise money as charities and spend it as campaigns.

The sector exploded. The Charity Commission's data shows human-rights charities operate overwhelmingly at national and international levels—82 per cent work both nationally and internationally, compared to just 24 per cent of charities generally. These aren't village organisations. They're professional networks, often with international connections, operating across borders, sharing staff and strategies with foreign NGOs.

Forty Charities Referred To Police

Which brings us to Gaza, and the 40 charities referred to police.

In November 2024, Orlando Fraser, chair of the Charity Commission, revealed the Commission had opened 200 regulatory cases related to the Israel-Hamas conflict since October 2023. Forty of those—forty—had been referred to police over suspected criminal offences, including "hate speech" and antisemitism.

Not forty political parties. Not forty news outlets. Forty registered charities, supposedly operating for the public benefit, had allegedly engaged in conduct serious enough to warrant police investigation.

This is the fruit of Blair's reforms. When you make "human rights" and "community cohesion" charitable purposes, when you build structures allowing charitable money to fund political campaigning, when you embed advocacy groups into the definition of civil society, you shouldn't be surprised when those groups take sides in the most polarising conflicts of our age.

"Charity has always been political"

The defenders say: charity has always been political. Victorian philanthropists had views. Religious charities promoted moral positions. The temperance movement was charitable.

True, but irrelevant. The temperance movement argued its position in public, raised money openly, and never pretended to be neutral. Everyone knew the Salvation Army was Christian. Nobody was confused about what the Lord's Day Observance Society wanted.

Today's "charities" trade on the word's traditional meaning—benevolent, trustworthy, non-partisan—while functioning as political pressure groups. They raise money from people who think they're supporting good works and spend it on campaigns those donors might violently oppose. The structure is deliberately opaque: charity funds company, company does politics, public sees only the charity's respectable face.

Worse, these organisations now form a permanent lobbying infrastructure, quasi-governmental in function, feeding policy proposals into Whitehall, seconding staff to departments, bidding for contracts, sitting on advisory boards. They're inside the system. The British state now pays charities to lobby the British state. It's circular, self-perpetuating, and perfectly legal under the framework Blair created.

Why Every Institution Speaks The Same language

Why does Britain feels politically captured? Why does every institution seem to speak the same language about diversity, inclusion, equity, decolonisation? Why you can't escape the sense of coordinated messaging on everything from climate to gender to migration?

Look at the charity sector. Look at what it became after 2006.

This wasn't evolution. It was engineering. Blair saw how American progressives had built institutional power through the non-profit sector and decided to replicate it in Britain. The Charities Act 2006 was the legal foundation.

The subsequent explosion of "human rights" and "equality" organisations was the superstructure. The integration of these groups into government policy-making was the consolidation.

And nobody voted for any of it.

The 2005 Labour manifesto didn't say: "We're going to redefine charity to mean political activism." The Charities Act debate in Parliament focused on technicalities—regulation, public benefit tests, registration thresholds. The revolutionary implications were buried in section 3, clause 2, subsection 2, paragraph (h): the advancement of human rights.

Nobody Saw It Coming

That phrase—nine words, slipped into a definition list—changed everything. It moved the boundary between charity and politics. It created space for organisations to be both charitable and campaigning. It allowed money to flow from donations into advocacy. It turned the charity sector into something Britain had never had: a permanent, tax-advantaged infrastructure for progressive politics.

Could this have been stopped? Possibly, if anyone had understood what was happening. The Conservative Party, then in opposition, was useless. They supported "modernisation" and "reform" without examining what those words meant. The Charity Commission was cautious but deferential to Parliament's intent. The churches, once the backbone of British charity, were declining and distracted. Small charities worried about compliance costs but lacked a voice.

By the time people noticed what had been built, it was too late. The system was embedded. Thousands of organisations, billions in funding, entire professional careers invested in the new structures.

Try now to say "human rights shouldn't be a charitable purpose" and watch the reaction. You're attacking charity itself. You want to defund vital work. You're on the wrong side of history.

Can Parliament Undo What Blair Did?

This is how institutional capture works. Change the rules quietly. Build the infrastructure. Wait ten years. Then claim the new arrangement is natural, obvious, unquestionable. Anyone who objects is attacking something now treated as fundamental.

Can it be unwound? Technically, yes. Parliament could amend the Charities Act, remove the contested purposes, tighten restrictions on political campaigning, ban or severely limit the charity-funding-company structure. The next government—if there is one—could do this.

Will it happen? Almost certainly not. The charity sector is now too large, too well-connected, too embedded in government. Any attempt at reform would be met with coordinated resistance: media campaigns, parliamentary lobbying, legal challenges, accusations of attacking civil society. The infrastructure Blair built is designed to defend itself.

What Charity Used To Mean

Which brings us to the deeper question: what is charity for? Is it private benevolence, freely given, serving purposes the donor chooses? Or is it part of governance, an instrument of social policy, advancing objectives the state defines?

For most of British history, charity was the former. Money given in trust, held apart from politics, serving specific purposes under law. The state protected charity precisely because it wasn't political. Charity trustees were stewards, not advocates.

Blair's reforms moved Britain decisively toward the latter model. Charity became an extension of social policy, integrated into government programmes, mobilised for political objectives. The sector was professionalised, funded by contracts and grants, measured by policy influence rather than service delivery.

This is the American model, and it comes with American pathologies. Politicised foundations. Advocacy groups masquerading as charities. Tax-exempt organisations functioning as party auxiliaries. A permanent bureaucratic-activist complex, insulated from democratic accountability, pursuing ideological goals under the banner of public benefit.

Britain took 400 years to build a charity sector focused on genuine need and rooted in local community. Tony Blair dismantled it in five years and replaced it with something unrecognisable.

Forgetting What We Lost

Your grandmother's charity was a trust for widows. Your charity is Political Radicalism Limited, funded by Impartial Nice People Charitable Trust, campaigning on issues you never asked about with money you thought was helping people.

That's not evolution. It's replacement. And it happened because one government decided charity should mean something different, passed a law most people never heard of, and waited for everyone to forget what charity used to be.

They've almost succeeded.

The generation now entering adulthood has never known anything else. For them, charity means advocacy. Human rights. Equality and diversity. Campaigning and lobbying. The old model—Lady Bountiful endowing hospitals, merchants leaving money for schools, churches running soup kitchens—seems quaint, paternalistic, even suspect.

But the old model had one thing the new model lacks: honesty. Nobody pretended the widows' fund was politically neutral. It was Christian charity, rooted in doctrine, administered by believers. You knew what you were getting.

Today's charities claim neutrality while doing politics. They claim to serve the public while advancing partisan positions. They claim to be civil society while being funded by government. The confusion is deliberate. Opacity is the point.

Tony Blair understood this. He'd spent the 1990s watching American progressives capture institutions through language, process, and law. He saw how changing definitions changed reality. He grasped that whoever controls the vocabulary controls the argument.

So he changed the definition of charity. Not in a dramatic way—no speeches about revolution, no manifestos about transformation. Just a quiet legal reform, technical and boring, debated in committee and passed on a Tuesday.

Twenty years later, we're living in the country he built. Where charities police speech. Where advocacy groups shape policy. Where the line between civil society and the state has dissolved. Where the old understanding of charity—service to the poor, funded by the rich, independent of politics—has been memory-holed so thoroughly that explaining it sounds like fantasy.

This is what institutional revolution looks like. Not barricades and proclamations. Clauses and subsections. Legal redefinitions. Regulatory guidance. Wait long enough, and the revolution becomes normal.

But here's the thing about legal changes: they can be legally changed back. The Charities Act 2006 is not holy writ. It's legislation. It can be amended. Repealed. Replaced with something closer to what existed before.

The question is whether anyone remembers what came before. Whether anyone understands what was lost. Whether anyone cares enough to fight for it.

Because if nobody does—if this generation accepts that charity means advocacy, and advocacy means politics, and politics comes wrapped in charitable clothing and funded by tax relief—then Blair's revolution is complete.

And your grandmother's charity is dead.