Liberty Vs. Authority: Different Ways To Solve Problems

Neither pure liberty nor absolute authority fixes it all. Successful societies, particularly what remains of Britain, must constantly navigate between these extremes through democratic institutions, finding sensible balance which adapts to circumstances while maintaining civic virtue and vigilance.

Remigration Now. Send them all back. Take back control. They all have to go. Someone needs to fix this. Nobody's listening. Why doesn't someone do something? Is the country lost? Endless questions circulate the motherland now, all draining the life out of our debate. One half want a whole world more liberty; the other half want order enforced.

In the grand theatre of political philosophy, no tension proves more enduring than the struggle between liberty and authority. This fundamental dichotomy shapes every society, every government, and indeed every political decision we make. On one side stands libertarianism, with its faith in human freedom as the universal solvent for social problems. On the other looms authoritarianism, convinced only firm control can bring order from chaos. Yet neither extreme offers a sustainable path forward on its own merits.

Britain, with its unwritten constitution and evolutionary approach to governance, provides a particularly fascinating laboratory for observing this dynamic. From the Magna Carta to Brexit, from the English Civil War to pandemic lockdowns, our history reads as a constant negotiation between individual freedom and collective authority. Understanding this balance isn't merely academic. It's essential for navigating our current political moment.

The Siren Song of Absolute Freedom

Libertarianism presents an intoxicating vision: remove the heavy hand of government, and human creativity and cooperation will flourish. Its advocates argue most problems stem not from too much freedom but from too little. They point to the remarkable innovations emerging from Silicon Valley's relatively unregulated environment, or to the prosperity generated by free markets compared to command economies.

John Stuart Mill, perhaps Britain's most influential libertarian philosopher, articulated this view brilliantly:

The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs.

This principle—the harm principle—suggests government intervention should occur only when individual actions directly harm others.

Yet pure libertarianism encounters immediate practical difficulties. Consider the tragedy of the commons, where individual rational choices lead to collective disaster. Without authority to regulate fishing quotas, oceans would be stripped bare. Without planning regulations, London would become an incoherent sprawl. Without financial oversight, markets periodically implode, taking innocent bystanders with them.

The 2008 financial crisis exemplified libertarianism's limits: years of light-touch regulation, championed as unleashing innovation and growth, instead enabled reckless speculation. When Lehman Brothers collapsed, the contagion spread globally, requiring massive government intervention—the very antithesis of libertarian principles—to prevent complete economic collapse. As economist John Kay observed:

The idea free markets invariably know best has been proved comprehensively wrong.

More fundamentally, absolute freedom for some often means oppression for others. The factory owner's freedom to set any wage confronts the worker's need for sustenance. The landlord's property rights clash with the tenant's need for secure housing. Freedom without structure devolves into the tyranny of the strong over the weak—a Hobbesian state where life becomes "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

The Iron Fist's False Promise

If libertarianism's weakness lies in its optimism about human nature, authoritarianism's flaw rests in its pessimism. Authoritarians view society as inherently chaotic, requiring firm leadership to maintain order. They promise security, efficiency, and clear direction—compelling offerings in uncertain times.

History provides numerous examples of populations willingly surrendering freedom for perceived safety. Germany's descent into fascism began with citizens exhausted by economic chaos and political violence. More recently, countries like Singapore demonstrate how authoritarian governance can deliver impressive economic growth and social stability, leading some to question whether democracy itself might be overrated.

The COVID-19 pandemic offered a masterclass in authoritarian temptation. Faced with an invisible threat, governments worldwide assumed emergency powers. China's harsh lockdowns initially appeared vindicated by low case numbers. Even liberal democracies implemented unprecedented restrictions on movement, assembly, and commerce. Many citizens not only accepted but demanded stronger government action.

Yet authoritarianism carries its own devastating costs. Lord Acton's warning rings eternal: "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Without checks on authority, leaders inevitably abuse their positions. China's zero-COVID policy, initially praised, became a humanitarian disaster as authorities prioritised political control over human welfare. Citizens found themselves locked in burning buildings, denied medical care, separated from dying relatives—all in service of an inflexible policy none dared question.

Moreover, authoritarian systems suppress the very creativity and adaptability societies need to thrive. Innovation requires questioning authority, challenging orthodoxy, taking risks—all anathema to authoritarian control. The Soviet Union could build impressive rockets but couldn't stock grocery shelves. North Korea maintains perfect political control while its people starve. Even Singapore, authoritarianism's supposed success story, struggles with innovation, relying heavily on importing foreign talent and ideas.

George Orwell captured authoritarianism's ultimate trajectory in "1984": "If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever." The promise of order through control inevitably descends into control for its own sake.

The Wisdom of Balance

Neither pure liberty nor absolute authority offers a viable path. Instead, successful societies navigate between these extremes, adjusting the balance as circumstances demand. This isn't relativism or fence-sitting—it's pragmatic recognition of complexity.

Consider Britain's response to terrorism. Following the 7/7 bombings, government sought expanded surveillance powers, arguing public safety required some sacrifice of privacy. Civil liberties groups resisted, warning against the surveillance state. The resulting debate—messy, contentious, ongoing—exemplifies democratic balance-seeking. We neither granted unlimited surveillance powers nor ignored legitimate security concerns. Instead, we crafted imperfect compromises, subject to judicial oversight and parliamentary review.

This balancing act requires constant vigilance. Edmund Burke understood this when he wrote, "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing." Democratic societies must actively maintain equilibrium between liberty and authority, resisting drift toward either extreme.

The balance point isn't fixed but contextual. During wartime, societies accept greater restrictions. Churchill's wartime government wielded extraordinary powers unthinkable in peacetime. Yet these powers came with temporal limits and democratic accountability. When victory came, voters immediately ejected Churchill, demonstrating democracy's self-correcting mechanisms.

Economic circumstances also shift the balance. The post-war consensus accepted significant state intervention—nationalised industries, comprehensive welfare, high taxation—as necessary for reconstruction and social cohesion. By the 1970s, this model struggled with stagflation and industrial strife. Margaret Thatcher's revolution swung toward liberty, privatising industries and reducing state involvement. Neither approach was inherently right or wrong—each responded to its moment's specific challenges.

The British Paradox

Britain presents a peculiar case study in liberty-authority balance. We lack a written constitution guaranteeing specific rights, yet maintain remarkable freedoms. We retain an unelected House of Lords and hereditary monarchy, yet function as a vibrant democracy. We invented the surveillance camera and maintain extensive anti-terrorism laws, yet also produced the Human Rights Act and freedom of information legislation.

This paradox reflects what Walter Bagehot called Britain's "dignified" versus "efficient" constitution. The dignified parts (monarchy, ceremony, tradition) provide stability and continuity. The supposedly-efficient parts (Parliament, Cabinet, civil service) enable adaptation and change. This dual structure allows Britain to combine authority's stability with liberty's flexibility.

We permit remarkable freedom of demonstration—Speaker's Corner symbolises absolute free speech. Yet we also maintain public order legislation, preventing protests from paralysing society. The balance isn't perfect—critics argue police powers have expanded excessively—but it avoids both American-style political violence and authoritarian suppression of dissent.

Our common law tradition exemplifies pragmatic balance: rather than grand constitutional principles, we build law through accumulated precedent, adjusting gradually to changing circumstances. This evolutionary approach lacks the clarity of written constitutions but provides remarkable adaptability. As Judge Learned Hand observed,

Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it.

Finding Balance In The Tension

Today's political landscape presents new problems to liberty-authority balance. Technology enables unprecedented surveillance—every phone a tracking device, every purchase recorded, every online interaction monitored. The Chinese social credit system demonstrates technology's authoritarian potential, while Silicon Valley's data harvesting shows how private actors can threaten liberty as much as governments.

Populist leaders claim to champion freedom against elite control, yet often govern in authoritarian fashion. They exploit democratic freedoms to gain power, then undermine democratic institutions. Hungary's Viktor Orbán exemplifies this paradox, using democratic mandates to construct what he calls "illiberal democracy"—an oxymoron revealing democracy's vulnerability.

Leave campaigners promised liberation from Brussels bureaucracy, restoration of parliamentary sovereignty, control over borders and laws. Yet implementing Brexit required extensive government intervention, from negotiating treaties to restructuring entire industries. The promised bonfire of regulations largely fizzled, as businesses discovered many EU rules served useful purposes. Freedom from one authority often means subjection to another.

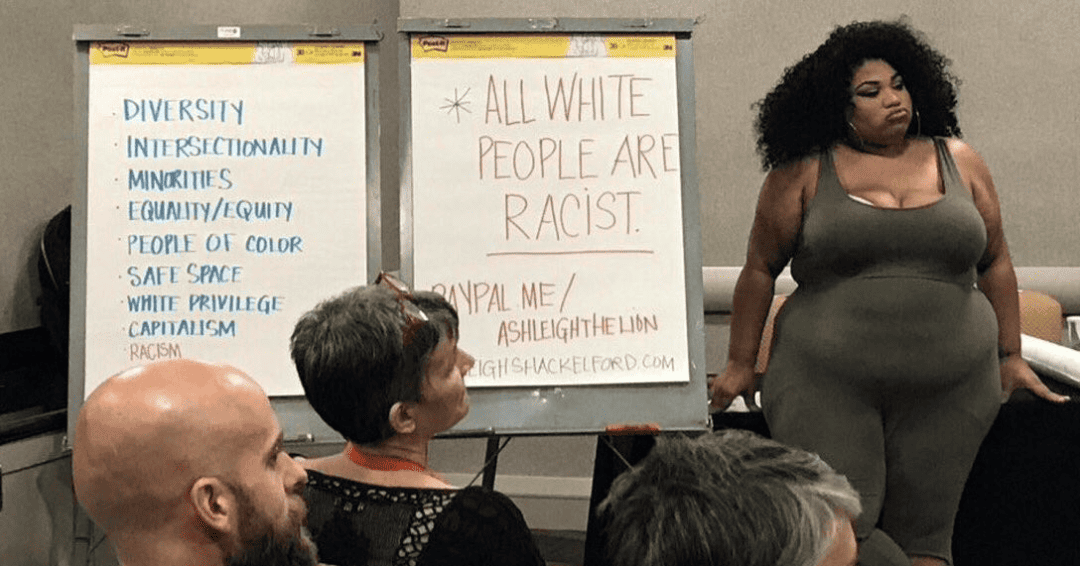

The culture wars represent another front in liberty-authority struggles. Progressive activists seek to expand certain freedoms—"gender" expression, sexual identity, racial "justice"—while restricting others—hate speech, discriminatory behaviour, historical symbols. Conservatives resist what they perceive as authoritarian impositions on traditional values and free expression. Both sides claim to champion freedom while seeking to impose their vision of proper social order.

Civic Virtue & Sensible Nationhood

How then should we proceed? First, we must reject extremism in either direction. History demonstrates both pure libertarianism and absolute authoritarianism lead to disaster. The answer lies not in splitting the difference but in intelligent, contextual balance.

Second, we must strengthen democratic institutions. These provide mechanisms for adjusting liberty-authority balance without violence or revolution. Independent judiciary, free press, competitive elections, civic organisations—these aren't obstacles to effective governance but prerequisites for it. As Karl Popper argued, democracy's value lies less in producing good government than in removing bad government peacefully.

Third, we must cultivate civic virtue. Rights without responsibilities lead to chaos; order without consent becomes oppression. Citizens must exercise freedom responsibly while holding authority accountable. This requires education, engagement, and what Tocqueville called "habits of the heart"—cultural practices sustaining democratic life.

Fourth, we must embrace complexity. Simple solutions—whether libertarian or authoritarian—cannot address complex problems. We need nuanced approaches recognising trade-offs, unintended consequences, and contextual variations. This frustrates ideologues but reflects reality's messiness.

Pure libertarianism would legalise everything, accepting addiction and social chaos as prices of freedom. Pure authoritarianism would impose draconian punishments, filling prisons without addressing underlying problems. Sensible policy navigates between extremes—decriminalising possession while targeting suppliers, treating addiction as health issue not criminal matter, allowing supervised consumption rooms while maintaining general prohibitions. It's unsatisfying to purists but works better than either extreme.

Difficult Problems Rarely Have Easy Answers

Britain faces crucial decisions about liberty-authority balance. Should we expand digital surveillance to combat terrorism and crime, or does this threaten fundamental privacy? Should we mandate vaccinations and health measures, or respect individual bodily autonomy? Should we regulate social media to prevent harm, or preserve free expression online? Should we impose economic controls to address inequality, or trust market mechanisms? Should we just remigrate them all, right now?

These questions lack easy answers. But we can identify principles for approaching them. Transparency matters. Citizens must understand what authorities do and why. Proportionality matters. Responses should match threats without excessive restriction. Accountability matters. Those exercising authority must face consequences for abuse. Reversibility matters. Emergency powers must expire, not become permanent.

Most importantly, we must maintain democratic dialogue. The tension between liberty and authority cannot be resolved through clever formulas or constitutional engineering. It requires ongoing negotiation among citizens with different local customs, interests, and experiences. This process, frustrating, inefficient, never-ending, is democracy's essence.

Isaiah Berlin distinguished between negative liberty (freedom from interference) and positive liberty (freedom to achieve potential). Both matter, but they often conflict. The freedom from taxation restricts freedom to access public services. The freedom from regulation limits freedom to breathe clean air. Navigating these tensions requires wisdom, compromise, and mutual respect.

Eternal Vigilance Is The Lesson

The struggle between liberty and authority will never end. Each generation must find its own balance, responding to new problems while learning from history. Britain's particular genius lies not in solving this tension but in managing it—maintaining remarkable stability while enabling necessary change.

Technological disruption, environmental crisis, geopolitical instability, social fragmentation—all pressure our democratic balance. Authoritarian solutions tempt with promises of decisive action. Libertarian solutions appeal with visions of unshackled potential. We must resist both temptations.

The answer lies in what Burke called "a manly, moral, regulated liberty"—freedom exercised within agreed constraints, authority wielded with consent and accountability. This requires citizens who are neither subjects accepting whatever authority dictates nor anarchists rejecting all collective action. It requires what Mill called "experiments in living"—trying different approaches, learning from results, adjusting course.

Comfort breeds complacency; crisis invites overreaction. We must guard against both, remembering democracy's fragility. As Ronald Reagan warned, "Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction."

Yet we should approach this challenge with confidence, not despair. Britain has navigated liberty-authority tensions for centuries, emerging stronger from each crisis. Our institutions, while imperfect, have proven remarkably adaptable. Our civic culture, while strained, remains fundamentally sound. Our commitment to democratic values, while tested, endures.

The pendulum will continue swinging between liberty and authority. Our task isn't stopping it but ensuring it doesn't swing too far in either direction. This requires engaged citizens, responsive institutions, and leaders who understand their role as temporary custodians of permanent values. It requires recognising both liberty and authority serve essential functions, neither sufficient alone.

In the end, perhaps Winston Churchill said it best:

Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.

The messy, inefficient, frustrating process of balancing liberty and authority through democratic negotiation remains humanity's best hope for combining freedom with order, innovation with stability, individual dignity with collective purpose. The dance continues, and we must all take our turn on the floor.