Nationalising Water When You Don't Understand Drains

Our worst MPs are fixated on nationalising water, without understanding sewerage, flooding, and drainage infrastructure is collapsing. It's cheaper for water companies to pay the fine than pay the state's infrastructure bill. Behold the perfect metaphor: socialism drowning in its own, actual s**t.

Every ninety seconds, somewhere in England, raw sewage pours into a river. Not as an emergency. Not as a catastrophic failure. As routine operation. Our MPs are obsessed with nationalising water, but have no idea what happens when it rains, or when they flush the toilet.

It's not sexy. It's not interesting. Frankly, it's rather revolting. But so is sewerage, and your house being flooded. It's the boring things which often decide the world.

Fifteen thousand overflow points, scattered across the country like relief valves on a pressure cooker that never stops boiling. The Victorian engineers who designed these systems intended them for storms of biblical proportion—once-in-a-generation deluges when every alternative had failed. Today they discharge in drizzle. They discharge when it is merely cloudy. They discharge because the alternative is sewage backing up through toilets and flooding into kitchens, and the choice between poisoning rivers and poisoning homes is apparently the best Britain can manage in the twenty-first century.

This is not an environmental crisis wearing infrastructure clothing. It is the opposite: an infrastructure collapse masquerading as weather events, regulatory failures, and the passive-voice inevitability of "pressure on the system." But pressure implies force applied from outside. What we face is internal rot—the compounding mathematics of deferred decisions, raided budgets, and a regulatory apparatus designed to manage decline rather than prevent it.

The sewers are failing because nobody will pay to replace them. The flood defences are failing because maintenance is invisible until it stops happening. And the two failures are now locked in mutual amplification: overloaded sewers discharge into floods, which spread contamination; floods overwhelm drains, which dump into sewers, which overflow again. A feedback loop playing out in hundreds of communities across England, where the same houses flood on the same streets in the same months, and every time the response is surprise, sympathy, and a promise to "learn lessons."

The lessons are already known. Victorian engineers learned them in 1858 during the Great Stink, when Parliament fled London's riverside chambers because the Thames had become an open sewer. Their response was to over-engineer—to build systems with capacity margins, gravity flow, and permanence baked into brick and portland stone. Modern Britain has learned the opposite lesson: build to minimum specification, optimise for financial return, and treat collapse as a cost of doing business.

The Arithmetic of Abandonment

Fifty to seventy billion pounds. That is the sum required—not for gold-plated excess, not for shiny new amenities—but simply to bring England's sewerage system to a standard appropriate for current use. Not future-proofed. Not climate-adapted. Just functional.

The useless National Audit Office estimates it will take 700 years to fix the water system. Yes, you read that correctly. Seven hundred years.

Compare this to the price caps Ofwat sets, the investment schedules companies propose, the incremental upgrades that make it into five-year plans. The gap is not a funding shortfall. It is a canyon. And everyone involved knows it cannot be bridged within the current model.

So the model continues. Companies invest what regulators allow. Regulators allow what they judge the public will pay. The public pays, and receives a service held together with monitoring equipment and crisis management plans. The sewers themselves—the physical pipes, the pumping stations, the treatment works—age beyond design life whilst spreadsheets track their "asset health" with colour-coded dashboards and projected failure probabilities.

Actual failure, when it comes, is often catastrophic. A trunk sewer collapses and an entire neighbourhood loses service. A treatment works floods and discharges millions of litres untreated. A pumping station fails and sewage lakes form in residential streets. These are classified as incidents, investigated, sometimes fined. But they are not aberrations. They are the statistically predictable outcome of running nineteenth-century infrastructure under twenty-first-century loading without substantive renewal.

The fines tell their own story. Record penalties sound impressive in headlines—tens of millions here, a hundred million there—but set them against the cost of actual infrastructure replacement and the arithmetic is brutal. A fifty-million-pound fine is less than a single major treatment works upgrade. It is a rounding error on the Thames Tideway Tunnel. It is, in corporate terms, the cost of continuing to operate as usual.

Water companies are not stupid. They employ engineers who know exactly what their networks need. They run models, they map failure points, they understand hydraulic capacity and biochemical loading. Then they pass this information to finance teams who calculate paying fines is cheaper than fixing infrastructure, and to communications teams who prepare statements about "unprecedented rainfall" and "lessons learned." This is not villainy. It is rational response to perverse incentives.

Who's paying for the failure to build infrastructure and account for the massive increase in population? Wait for it. You'll be surprised. You are.

Maintenance: The Expenditure That Disappears

New flood defences are announced with fanfare. Ministers visit sites. Photos are taken beside earth movers and concrete pours. Capacity figures are cited. Communities are reassured.

Then the budgets are set. Capital projects receive allocation. Maintenance receives what remains. And what remains is rarely enough.

A flood defence scheme is only as good as its least-maintained component. A pumping station rendered inoperable by lack of servicing. A culvert blocked because clearance was postponed. A drainage channel silted because dredging was "deferred pending budget review." These are not dramatic failures. They do not generate inquiries. They simply mean the system designed to prevent flooding no longer does.

Internal Drainage Boards—those unglamorous bodies responsible for keeping lowland Britain from reverting to marsh—have been hollowed out across much of the country. Reduced coverage. Minimal staff. Responsibilities fragmented between councils, highways authorities, and the soviet Environment Agency in a way which ensures when something goes wrong, identifying who should have prevented it becomes an exercise in bureaucratic archaeology.

Culverts are perhaps the perfect symbol of this quiet abandonment. Critical drainage infrastructure, often centuries old, frequently inaccessible, almost never inspected until failure. When they block or collapse, surface water backs up, roads flood, properties are inundated. The failure is usually attributed to extreme weather—and extreme weather may indeed be the trigger—but the vulnerability is entirely man-made. Or rather, maintenance-unmade.

Local authorities know which drains are at risk. Highways departments know which gullies need clearing. The Environment Agency knows which channels require dredging. This knowledge sits in asset registers and risk assessments, beautifully documented, whilst the actual work goes undone for lack of budget or because political capital flows toward visible projects rather than invisible prevention.

Building Risk Into the System

Flood risk assessments are carried out. The Environment Agency provides formal objections. Sequential tests are meant to ensure development happens in safer locations first. Mitigation measures are proposed: permeable paving, attenuation ponds, swales to slow runoff.

Lots of important Civil Service paper-shuffling. "Months of fruitful work," as Sir Humphrey would say.

Then planning permission is granted anyway.

The reasons vary—housing need, economic development, local plan targets—but the outcome is consistent. Homes are built on land where flooding is not a theoretical risk but a documented pattern. The promised mitigations are installed, sometimes. They are maintained, rarely. Enforcement is sporadic to non-existent.

The new development increases impermeable surfaces. Rainwater which once soaked into fields now runs off roofs and driveways into Victorian drains designed for a fraction of current flow. Those drains overwhelm. The sewers they connect to overflow. And the flooding—now carrying sewage—damages both the new properties and the existing communities downstream.

Private insurance data reveals the pattern with uncomfortable clarity. The same postcodes flood repeatedly. Sometimes the same individual properties claim year after year. These are not random weather victims. They are people living in hydraulic failure zones planning authorities approved for development despite knowing the risk.

The justification is often modern building standards include flood resilience—raised floor levels, water-resistant materials. This is risk management through adaptation: accepting flooding will happen and building accordingly. It is also tacit admission of infrastructure defeat. We can no longer promise to keep water out, so we promise to make it less catastrophic when it gets in.

The Crisis Without a Department

River flooding makes news. It has drama, imagery, clear causation. Coastal flooding has similar appeal—storm surges, breached defences, entire communities cut off.

Surface water flooding has none of this. It is prosaic. Drains backing up. Water pooling in roads. Sewage overflowing through manhole covers. It affects far more properties than river flooding but generates a fraction of the coverage or investment.

Responsibility is magnificently unclear. Is it sewerage, therefore water companies? Is it drainage, therefore highways? Is it flood risk, therefore the Environment Agency? Is it planning failure, therefore local authorities? The answer is usually some combination, which in practice means everyone can point elsewhere.

When surface water floods a home with sewage, the contamination makes the damage exponentially worse. Clean floodwater can sometimes be mopped up, dried out, repaired. Sewage requires professional decontamination, disposal of furnishings, often structural work. Insurance claims multiply. Health risks emerge. Properties become uninhabitable for months.

And this is increasingly the standard mode of flooding in England. Not rivers bursting their banks but drains overwhelmed, sewers backing up, the mundane infrastructure of daily life failing under loads it was never designed to handle.

When Two Failures Become A Supercrisis

Heavy rainfall hits an area where urban development has increased runoff. The drainage system, poorly maintained, struggles to cope. Surface water begins pooling. The water enters combined sewers already operating near capacity. The sewers overflow through storm discharges, releasing sewage into watercourses and, increasingly, into the floodwater itself. The contaminated flood spreads across a wider area. Properties that might have avoided river flooding are inundated by sewage-laced surface water. The cleanup costs multiply. The health impacts worsen. And the next rainfall event starts the cycle again.

This is not two separate problems happening simultaneously. It is a single integrated failure mode where each component breakdown amplifies the others. Sewerage and flooding are now locked together in a death spiral of mutual degradation.

Regulatory fragmentation ensures no single body can address this holistically. Ofwat regulates economic performance of water companies but not flood risk. The Environment Agency manages environmental compliance and flood defence but not sewerage investment. DEFRA sets policy but doesn't operate infrastructure. Local authorities handle planning but don't own the drains or sewers.

Complex reporting requirements proliferate. Data is collected, dashboards updated, compliance tracked. But nobody has both the authority and the budget to fix the underlying physical systems. And so we manage decline—monitoring failure rates, investigating incidents, consulting on strategies—whilst the infrastructure rots.

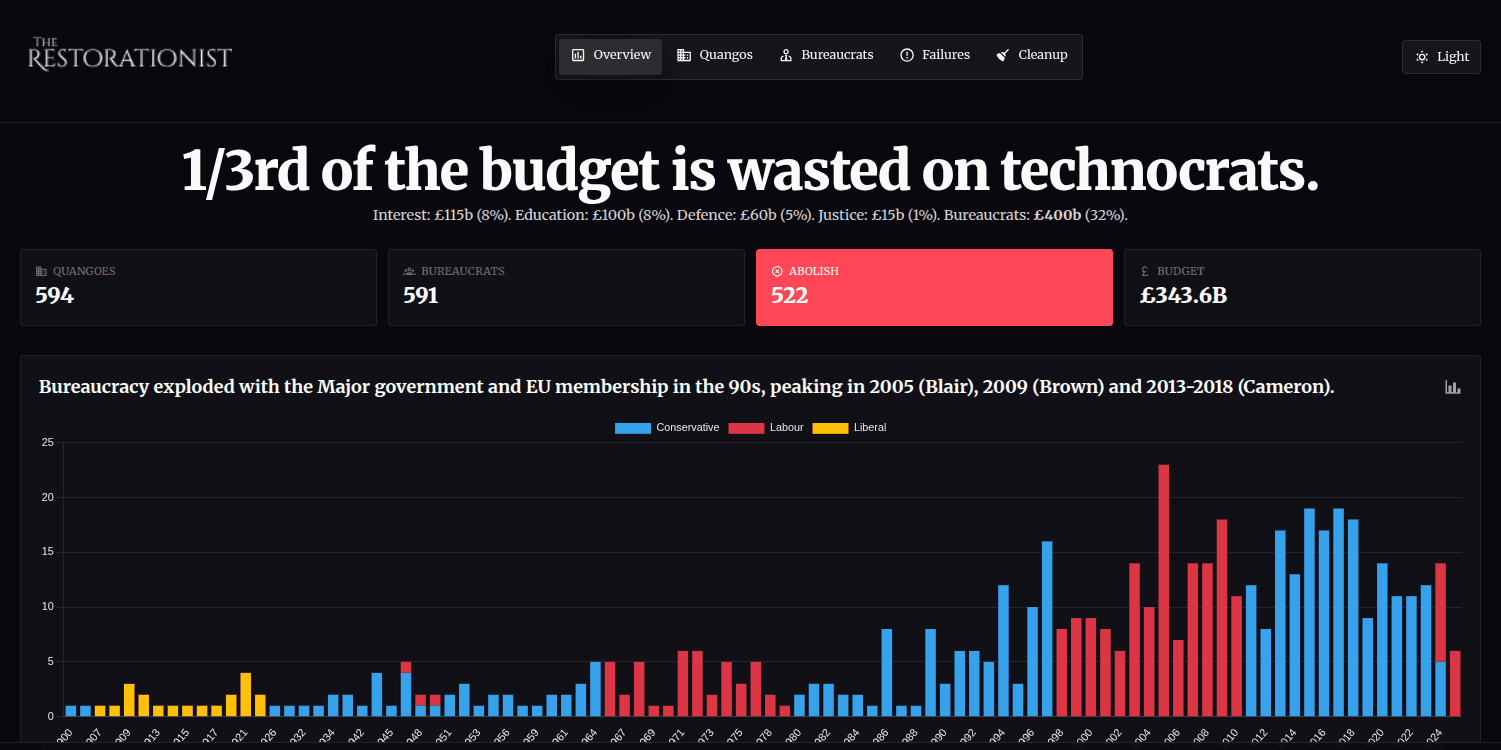

Eurocommunist Technocracy Can't Build

Joseph Bazalgette's London sewer system, opened in 1865, was designed for a population of four million. It still serves ten million. Bazalgette over-engineered deliberately, building in capacity margins because he understood that cities grow and demands change. The system was not optimised for construction cost or minimum viable specification. It was built to last.

Blair's Britain and its "modern" technocracy builds differently, if at all. Regulatory frameworks demand a useless, endless chain of bureaucracy: value-for-money assessments, competitive tendering, optimised delivery. Engineering margins are seen as waste. Systems are designed to minimum acceptable standards, on the assumption future upgrades will handle future needs.

But the future upgrades don't come. Or they come piecemeal, addressing local failures without systemic renewal. Or they are proposed and then cut when budgets tighten. And the infrastructure ages past its design life, operated beyond capacity, held together by monitoring and reactive maintenance.

The contrast is not merely aesthetic or philosophical. It is mathematical. Victorian infrastructure was built with redundancy. Modern infrastructure is built to assumptions: maintenance will happen, upgrades will be funded, population and climate will behave as modelled – presumably by the EU, or something. When those assumptions fail—and they are failing across England—the systems collapse.

We have replaced permanent infrastructure with permanent management. Asset registers instead of assets. Risk assessments instead of resilience. Monitoring regimes tracking the decline of systems we have collectively decided not to renew.

The Wilful Blindness of Repeated Crisis

When the same properties flood multiple times, what precisely are we learning each time? When insurance companies map repeat claims down to individual addresses, when councils maintain flood risk registers identifying specific failure points, when residents can predict to the week when their street will flood—what more evidence is required before we admit these are not extreme weather events but known infrastructure failures left unaddressed?

The language of surprise is a strategy.

- "Unprecedented rainfall" absolves decision-makers of culpability.

- "Extreme weather" suggests forces beyond human control.

- "Lessons will be learned" implies problems identified for the first time.

All of it is performance, repeated after each predictable crisis.

The residents know. They sandbag the same doors. They move furniture to upper floors every autumn. They file insurance claims they know will come. They listen to officials express shock at events they themselves anticipated, and they wonder who precisely is being protected by this pantomime of ignorance.

Inability, Incompetence, And Irresponsibility

Here is the impermissible thought: perhaps the current regulatory and ownership structure is simply incapable of maintaining national infrastructure at scale.

Not because of individual incompetence. Not because of regulatory capture or corporate greed—though these may feature. But because the financial model fundamentally cannot generate the capital required for full asset renewal whilst delivering returns to investors and meeting price caps judged politically acceptable.

The numbers don't work. They have never worked. And every five-year regulatory cycle repeats the same pattern:

- assessments identify vast renewal needs,

- companies propose partial programmes,

- regulators approve what they judge affordable,

- infrastructure continues aging beyond design life.

The alternative—full nationalisation, complete restructuring, unlimited public investment—carries its own risks and costs. But pretending the current model is merely experiencing teething troubles requires ignoring thirty-five years of evidence. This is not a transition phase. This is the steady state.

We have built a system optimised for financial stability and regulatory compliance, not infrastructure renewal. And when those objectives conflict—which they do constantly—the pipes lose.

Everyone Responsible, No-one Accountable

When flooding occurs, who exactly is responsible? The water company for sewage discharge? The highway authority for blocked drains? The local authority for planning decisions? The Environment Agency for maintenance failures? DEFRA for policy? Ofwat for investment limits?

All can point to constraints beyond their control. Water companies to price caps and regulatory limits. Regulators to statutory duties balancing multiple interests. Local authorities to funding cuts and housing targets. Central government to fiscal pressures and competing priorities.

The result is an accountability diffusion where responsibility is divided so thoroughly that no entity can be meaningfully held to account for systemic failure. Penalties exist for specific violations—a documented discharge, a planning breach, a missed compliance target. But the slow compounding failure of infrastructure maintenance and renewal sits below this layer, invisible to enforcement mechanisms designed for discrete incidents rather than systemic decay.

Residents flooded repeatedly can complain to their water company, their council, their MP, their insurer. Each will express sympathy, cite constraints, and refer to another body. The resident's home remains flood-prone because the infrastructure failure causing it sits in a regulatory no-man's-land where everyone has a reason it's not their problem to solve.

The True Cost of Deferral

Infrastructure failure is not evenly distributed. Some communities flood whilst others remain dry. Some streets are unaffected whilst adjacent roads become rivers. The correlation with property values and political influence is rarely discussed but consistently evident.

The cost of this failure is measured in ruined homes, impossible insurance premiums, uninhabitable properties, and communities gradually abandoned as flooding becomes routine. It is measured in health impacts from sewage contamination, in childhood asthma from damp housing, in stress-related illness from repeated displacement.

It is measured in economic blight as businesses relocate, property values collapse, and areas acquire reputations as flood zones from which recovery becomes near-impossible. And it is measured in the gradual acceptance that certain places in England simply cannot be protected to modern standards because fixing the infrastructure would cost more than the political system will bear.

We are making choices about which communities to sacrifice. We simply refuse to state them plainly.

The Endgame: Collapse or Renewal

England's sewerage and drainage infrastructure is approaching a decision point. Continue the current trajectory and failures will compound until they force crisis response—systems breaking down faster than reactive repairs can address, environmental damage requiring emergency intervention, public health implications too severe to manage through statistics.

Or confront the true scale of investment required, accept that the current model cannot deliver it, and restructure both funding and ownership to prioritise physical renewal over financial optimisation.

You may not care now. You will when you lose your home, or when your high street starts being covered in sewerage. But that's someone else's problem to fix, right?

The choice is not whether to spend the money. It is when and under what circumstances. Controlled renewal now, or crisis management later. The sums involved are eye-watering either way, but deferral adds interest: environmental damage that takes decades to reverse, property damage that destroys communities, public health costs that multiply with each contaminated flood.

Victorian engineers faced cholera and the Great Stink. They responded with Bazalgette's sewers, massive interceptor schemes, and treatment works built to last. The crisis forced action the political class had delayed for decades.

We are manufacturing our own crisis through precisely such delays. Every year of deferred renewal adds to the eventual bill. Every flood season demonstrates the cost of pretending maintenance is optional. Every sewage discharge into rivers signals infrastructure pushed beyond sustainable limits.

If you import twenty million people to fund expansion of the state, grossly inflating the population – then fail to upgrade the infrastructure – blaming it on the water companies for not paying the bill only washes so long.

The choice is ours: act now whilst controlled renewal remains possible, or wait for catastrophic failure to force intervention under the worst possible conditions. But the one thing we cannot do is continue as we are and expect different results.