NeoParty: A Blueprint For A New British Political Party Of The Sensible Centre Right

Country, family, children. A natural habitat for the politically homeless who reject extremism and value common sense. The Restorationist™ today publishes a full, open source blueprint for a new centre-right party in Britain which targets 326 seats with a Great Repeal and scales to millions.

British politics is broken, and everyone knows it. The Conservatives have abandoned conservatism, Labour offers managed decline with a smile, and the alphabet soup of protest parties—Lib Dems, Greens, Your Party, Reform, UKIP, Homeland, Restore, Heritage—splinter what remains of the opposition into irrelevance. Voters recognise the pattern: charismatic leaders making bold promises, initial enthusiasm, then collapse into factional warfare, financial chaos, and electoral oblivion.

The graveyard of failed parties stretches back decades, each convinced their passion and good intentions would overcome the brutal mathematics of British electoral politics. They were wrong.

Every successful party in British history—Conservative, Labour, even the long-forgotten —succeeded because they understood something their competitors did not: political parties require six elements working in concert. A doctrine which unifies belief. An institution which preserves and advances ideas. Backers providing the capital to operate. A publication through which to speak with authority. A party structure capable of fielding candidates. A network through which to recruit and evangelise.

Remove even one element and the structure collapses, no matter how popular the leader or righteous the cause. The current crop of alternatives possess at most three elements. This is why they fail, and will continue to fail, until someone builds all six simultaneously.

This document presents that blueprint. Not another protest movement, not another vehicle for a television personality, not another well-meaning shambles of volunteers meeting in pub back rooms.

This is a design for a mass-membership political party capable of scaling to thirty million members, fielding eight hundred professional candidates, raising billions in transparent funding, and targeting the 326 Parliamentary seats required to form a government. It assumes nothing beyond what has already been proven possible by existing British institutions, and demands nothing beyond what serious participants in democratic politics should willingly provide. The structure draws from community benefit societies, Estonian e-governance, Swiss direct democracy, and the organisational principles of successful corporations—all adapted to the specific requirements of British constitutional politics.

The ambition is not to win a handful of seats and play kingmaker in a hung Parliament. The ambition is to replace the Conservatives as the natural party of the centre-right, to provide a genuine governing alternative, and to implement a programme of constitutional restoration which reverses a century of institutional decay.

This requires thinking beyond the next election cycle. It requires building institutions that outlast their founders. It requires understanding game theory, electoral mathematics, and the cold reality good intentions without institutional capacity produce nothing but disappointment. Reform, for all its current polling strength, lacks the institutional foundations for long-term success. Labour's grip on power depends on Conservative incompetence and Reform's vote-splitting. The opportunity exists, but only for those willing to build properly.

What follows is open source: the legal structures, the governance mechanisms, the financial models, the examination syllabi, the targeting strategies—all published without restriction. If this blueprint succeeds, it is as a genuine mass movement of qualified, invested citizens who choose to build something remarkable together. If it fails, it fails because we were wrong about what British voters want, not because we lacked the institutional architecture to deliver it. The question is not whether this can be built. The question is whether enough sensible people recognise that their country desperately needs it built, and are willing to do the work.

The 6 Elements

For any party to succeed, it must have six pillars. If it has them all, it succeeds long-term. If it does not have them, it fails.

- A doctrine it agrees on;

- An institution which vanguards its ideas;

- Backers providing money to operate;

- A publication through which it can speak;

- A party which can stand representatives for Parliamentary seats;

- A network through which it can recruit.

The successful parties of the United Kingdom have all six. For example, the most successful and oldest party in the world is the Conservative party, aka the Tories.

- Conservatism (Burke/Peel)

- 1922 Committee/CCHQ

- City of London

- The Telegraph (also the Daily Mail, Express, etc.)

- Conservative Party

- Constituency associations

Labour also conforms to this pattern:

- Democratic socialism (Eurocommunism)

- Fabian Society

- Trade unions

- New Statesman (also the Mirror, Morning Star, etc.)

- Labour Party

- "Movement" groups, unions

If we contrast the least successful, we see the opposite pattern. For example, the British National Party (BNP) and the Socialist Workers Party (SWP):

- Nationalism / Trotskyism

- ?

- Subscription / students

- Bulldog / Socialist worker

- BNP / Front groups (e.g. Respect)

- Football stands / protest groups (e.g. SUTR, CND)

Reform, the Lib Dems, UKIP, SNP, DUP, Plaid, Greens, Restore, Homeland, Advance UK all suffer the same problem. They lack at least three (half) of the six elements, perhaps more.

- Reform's doctrine is Thatcherite neoliberalism, a limited company, member subscriptions, no publication (other than the GB News Farage show), and a disaffected Tory-lite electorate who will desert them for a resurgent Tory party overnight;

- The Lib Dems' and Greens' doctrine is social democracy (aka socialism lite), wealthy donors, and the Guardian, with a mixture of federated student protestors who grow middle-aged.

- The SNP and Plaid's doctrine is ethno-socialism with a mixture of member subscriptions and wealthy donors, but they have The National and Nation.Cymru. Their networks are constituency associations and eisteddfods (festivals).

- Advance UK and "Your Party" have no doctrine, but member subscriptions.

- UKIP's doctrine is nationalism, with limited wealthy donors.

- Homeland's doctrine is nationalism, but they have no donors despite well-organised recruiting networks.

- Restore, English Democrats, Heritage etc have little or none of the elements at all.

None of them have all six. Parties which succeed institutionalise cleverly below their charismatic leadership, and voters tick the box because they recognise it.

- It is not enough to have ideas. You need to formalise what you believe into a written doctrine which is testable by the electorate.

- It is not enough to be a 60s-style "movement." You need to create something concrete which is real, with governance paperwork and a bank account.

- Offices, ads, and salaries cost money.

- It's not enough to rely on people believing the same thing. You need thought leadership and a means to indoctrinate it.

- You need to be formally registered with the Electoral Commission to take part in an election.

- If you can't evangelise and bring in new people, you can't grow or build.

The pattern is unmistakable and undeniable: all of these parties fail because they ignore the formula. They get five out of six, and don't realise anything but a perfect score (6/6) is a fail.

Messaging & Beautiful Branding

Our positive messaging is simple: love of country, family, children.

- A deep love of our broken country, which we want to fix and heal.

- A deep love of marriage and family, which provide the basis and fabric of it.

- A deep love and concern for children, who we are doing it for.

Parties have colours, and the basic ones are taken. Most of them are awful; particularly Reform, whose teal shading is worse than dreadful Bermuda shirt from the Boomer eighties.

- Conservatives: boring blue

- Labour: communist red

- Reform: ocean teal

- Lib Dems: parking orange

- SNP: cowardly hi-vis yellow

- Greens: environmental green

- Sinn Fein: Irish dark green

- DUP: Ulster orange

- Advance/Restore: union jack dark blue

- UKIP: royal purple

All of these are ugly. We need beautiful modern technology aesthetics which work on white background and in "dark mode." The logo needs to be simple, but doesn't matter for now; we'll make do with arrows to demonstrate the point but we could add any other shape, for example, love hearts.

Let's pick a tri-tone pastel scheme we might find in Silicon Valley. There are plenty of tools to help with colour theory.

What this potentially represents and recalls:

- Movement and progress (tire tracks, motorway signs);

- Direction rightwards;

- Unity and synchronisation;

- Father, mother, children;

- Family, children, country;

- Status quo, love, output/result;

- Military rank insignia;

Let's add a modern san-serif font (Poppins) with our bland placeholder name.

We can play around a lot with this.

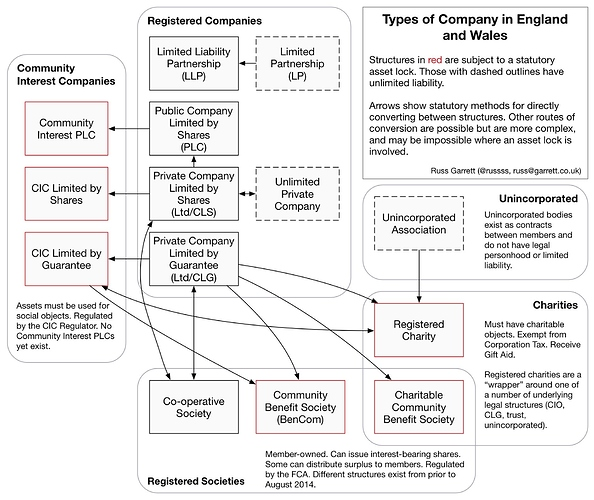

FCA/BenCom Incorporation & Numbers

The issue of incorporation revolves around legal personality. Limited companies like Reform and Advance are too opaque. Conversely, charities are not permitted to have a political purpose. We need middle ground: a social enterprise.

A Community Benefit Society (BenCom) is a corporate body under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014. It can employ staff; own property; sue and be sued; hold IP; and sign leases. A conceptual example is the National Trust or Nationwide Building Society. The CBS/BenCom itself is the political party registered under PPERA 2000.

It must exist primarily for the benefit of the community, not private members. It must be explicitly political without being a charity. It is a statutory corporate vehicle registered with the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). It can engage in political campaigning, research, advocacy, public policy, training, and issue-based mobilisation.

Its purpose might be:

To promote the improvement of public administration, integrity in public life, democratic participation, constitutional education, and accountable governance in the United Kingdom.

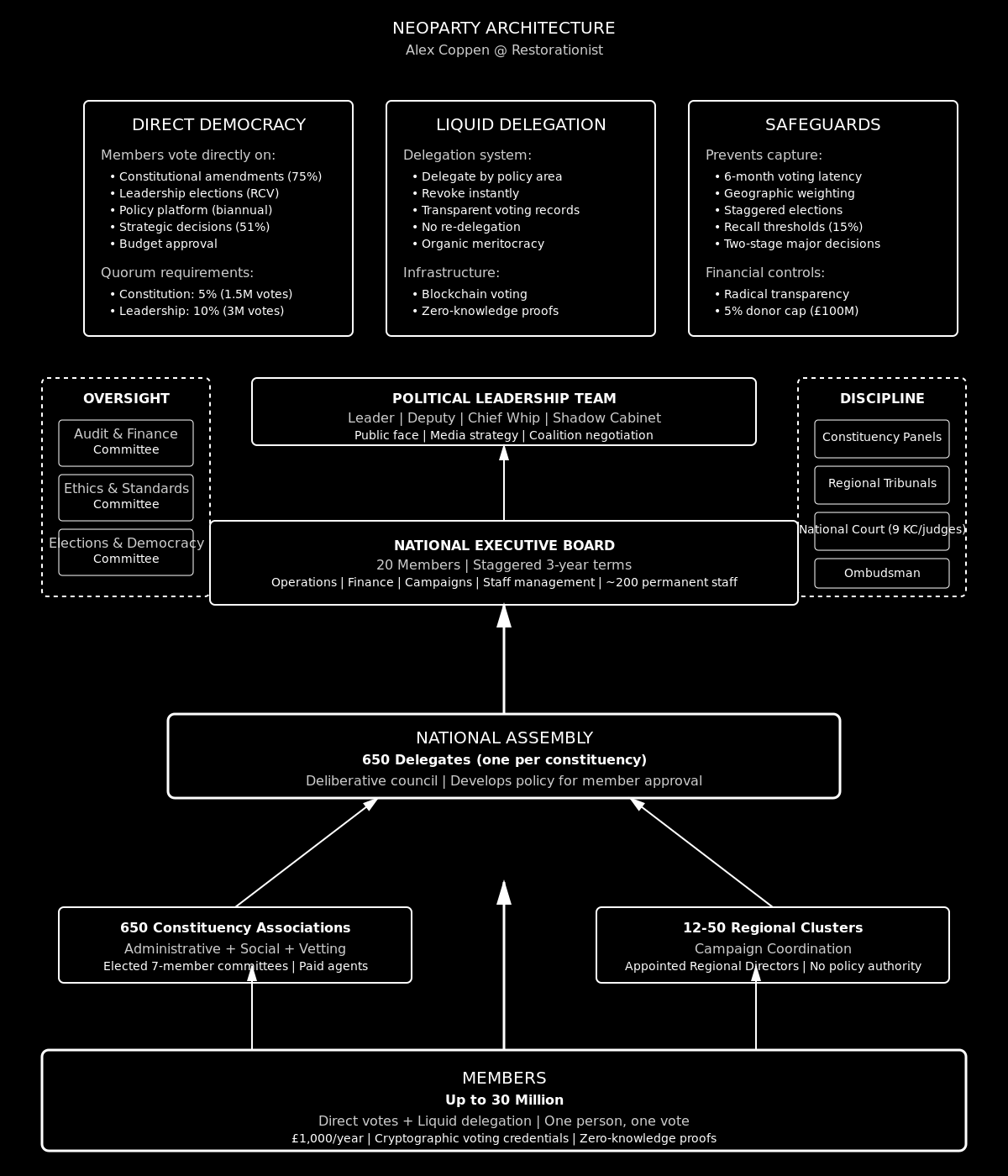

A large political BenCom led by a National Executive Board (20) elected by all members for 3 years to run governance and operations, a Political Leadership Team (Leader, Deputy, Treasurer, Nominating Officer, or 4 -6 people) responsible for political direction, and a National Assembly of elected delegates (650, or one per Parliamentary seat) which sets policy and holds leadership to account. Independent committees provide audit, ethics, and electoral oversight, ensuring transparency and preventing concentration of power.

Parliament has 650 seats. 326 (50% + 1) are required for a basic majority. The Lords has 826 members and no upper limit. Each parliamentary seat costs £500 to stand in, refundable only if you receive more than 5% of the valid votes in the constituency.

- England: 543 seats

- Scotland: 57 seats

- Wales: 32 seats

- Northern Ireland: 18 seats

- Total: 543 + 57 + 32 + 18 = 650 seats

That means 650 x £500 = £325,000 per election, with up to £162,500 potentially lost each time as the cost of doing business. If we recruit 800 to be sure, we have a reserve contingency factor of 23.1% assuming just under a quarter drop out or are disqualified somehow.

The 650-seat internal Assembly, one seat per constituency, are elected as representatives into those seats (with many seats initially merged or unfilled). The Assembly becomes the BenCom’s main representative body, sitting above the general membership and overseeing the National Executive.

A candidate may spend up to £11,390 plus £0.08 (8 p) per registered electorate in a “borough/burgh” constituency or £11,390 plus £0.12 (12 p) per registered electorate in a “county” constituency. If the constituency has 72,021 electors, the limit would be £11,390 + (72,021 × £0.12), or about £20,033.

A political party has a spending limit calculated as a) either a fixed minimum figure for each of England/Scotland/Wales, or b) £54,010 × (number of seats the party is contesting in each part of Great Britain). For a party contesting all 543 constituencies in England (not the UK), the limit would be 543 × £54,010 = about £29.3 million.

One single donor alone could fund all those candidates and their ad budget as their venture capital lunch bill. A startup in San Francisco wouldn't get out of bed for that money.

We need to find 800 qualified tradespeople or professionals of sensible mind and clear track record.

That's not hard. These companies do it every day with HR departments:

- Walmart: 2.1 million

- Amazon: 1.5 million

- Foxconn: 1 million

- Accenture: 740,000

- Tata Group: 700,000

- Volkswagen: 640,000

- Berkshire Hathaway: 383,000

For theory, let's assume the magical donor who pays for everything fails to materialise.

Immigration Entry Requirements For The 800

Any future member or backer of the party is on probation for three years. If immigrating into politics, they must:

- Be aged 25 and over, born in the UK, and have been a single-nationality, NI/tax-paying British citizen for the previous 10 years;

- Submit a cheque for £1500, covering:

- £500 election candidate fee;

- £1000 general party funds buy-in;

- Unless they:

- Are sponsored financially by others, or

- Are waived for a scholarship on the grounds of exceptional ability.

- Be qualified/certified in a trade, profession, or otherwise demonstrable life experience.

- Pass an academic entrance exam (see below).

- Voluntarily submit to background check vetting and party disciplinary procedures;

- Renounce extremism, and have had no links to it in the last 5 years (otherwise be placed on extended probation):

- Extremism means unilateral imposition of political will without negotiated democratic consensus in Parliament;

- No BNP, UKIP, PA, Britain First, racial separatism, fascism, nationalism socialism, etc;

- No sectarianism rejecting the Union or the Monarch's coronation oath to be the defender of the faith (e.g. Plaid, SNP, Sinn Fein, Islamism);

- No Communist party, Militant Tendency, radical sedition, vigilantism, Fabian incrementalism, anarchism, or SWP.

- Have no major criminal record, financial impropriety (e.g. bankruptcy), or background involving concerns of moral turpitude (e.g. abortion) or mens rea (e.g. fraud).

- Have no reputation or involvement with causes which could bring the party into public disrepute or pejorative controversy (i.e. the Tommy Robinson clause).

- Sign a legally-binding covenant – under oath – governing confidentiality, integrity, transparency, honourable behaviour, and the commitments one agrees to undertake;

- Pay £1000 annual membership fees into general party funds under the same grounds as 2(c), or be honourably suspended.

Why the fees? Parties need money, and candidates need skin in the game. You are less likely to wreck or sabotage something you had to pay/earn your way into, because you value it when it costs you. Politics is exclusive, not inclusive. You are smart and clean enough, or you are not. The party can rely on X per year, or it can't.

Why all the demands? Our country is in serious, serious peril. We cannot afford to waste time worrying about whether someone is qualified or trustworthy when we need to be writing legislation.

Backers must declare their interests and donations openly, and submit to the same due diligence vetting as anyone else. No anonymous NGO dark money; no sponsoring puppets; you put your name next to your cash, in public.

This gives us:

- An initial budget of £1,200,000.

- Our election budget of £325,000.

- Remaining £875,000, or 800 checks - (650 seats x £500 fee).

- A yearly recurring party budget of £800,000 (800 checks x £1000 annually).

- Room for individual donors to boost party funds (e.g. black tie dinner donations of £5M or £10M).

- 800 qualified and invested candidates.

Entrance Exam & Certification

Do you have actually have any idea about political theory, economics, or philosophy? Can you tell the difference between left, right, liberty, and authority? Do you know the difference between negative and positive rights, or what makes negative liberty the opposite of positive liberty?

Back in the days of the tripartite system, we had the 11+ examination as default. It's crucial to understand what skills and abilities different people have, and to ensure they are qualified.

How? AI-assisted home learning using Harvard's Open EDX.

At a minimum, parliamentary candidates need to demonstrate proficiency in the following:

1. Knowledge of British History, Constitution, and Institutions

The examination shall test the candidate's comprehensive knowledge of:

- The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the establishment of feudal governance structures

- Magna Carta 1215, its historical context, the barons who compelled King John to seal it, the specific limitations upon royal prerogative contained therein, and subsequent reissues and confirmations

- The development of Parliament from the thirteenth century, including Simon de Montfort's Parliament of 1265, the Model Parliament of 1295, the separation of the Commons from the Lords, and the evolution of representative institutions

- The English Reformation from 1534, the Act of Supremacy, the dissolution of the monasteries, religious settlements under successive monarchs, and constitutional implications

- The English Civil Wars 1642-1651, conflicts between Crown and Parliament, the trial and execution of Charles I, the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell, and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660

- The Glorious Revolution of 1688, the flight of James II, the accession of William III and Mary II, the Bill of Rights 1689, and the establishment of Parliamentary supremacy

- The Acts of Union 1707 creating Great Britain, and 1800 creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

- The Reform Acts of 1832, 1867, and 1884, the extension of the franchise, the redistribution of Parliamentary seats, and the gradual democratisation of representation

- The Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949, the limitation of the powers of the House of Lords, and the supremacy of the elected House of Commons

- The Government of Ireland Act 1920, the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922, Partition, and the creation of Northern Ireland

- The Statute of Westminster 1931 and the development of the Commonwealth

- The devolution settlements: Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, Northern Ireland Act 1998, and subsequent amendments

- The European Communities Act 1972, membership of the European Economic Community and European Union, and the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

- The Human Rights Act 1998 and its incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic law

- The Constitutional Reform Act 2005, the creation of the Supreme Court, and reforms to the office of Lord Chancellor

- The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 and its subsequent repeal by the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act 2022

- The structure, functions, and powers of the House of Commons, including the role of the Speaker, the whip system, standing orders, and procedures for legislative debate

- The structure, functions, and powers of the House of Lords, including the categories of membership (life peers, bishops, hereditary peers), conventions governing its conduct, and its relationship with the Commons

- The role and powers of the Sovereign, including Royal Prerogative, Royal Assent, the summoning and dissolution of Parliament, and constitutional conventions limiting monarchical power

- The office of Prime Minister, the formation of governments, collective Cabinet responsibility, individual ministerial responsibility, and the confidence of the House of Commons

- The structure of His Majesty's Government, including departments of state, the Cabinet, Cabinet committees, the civil service, and the doctrine of ministerial accountability

- The constitutional role of the judiciary, the independence of judges, the separation of powers, judicial review, and the relationship between courts and Parliament

- The territorial constitution of the United Kingdom, the governance of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and intergovernmental relations

- The constitutional doctrines of Parliamentary sovereignty, the rule of law, constitutional conventions, and the uncodified nature of the British constitution

- The electoral system for the House of Commons, constituency boundaries, the conduct of elections, and electoral law

- The operation of political parties, party funding, party organisation, and the role of opposition parties

- Local government structures, powers, and financing in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland

- The honours system, peerages, the Privy Council, and other constitutional institutions

- Major constitutional crises, precedents, and controversies throughout British history

- The relationship between the United Kingdom and the Crown Dependencies (Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man) and British Overseas Territories

2. The Supremacy of Parliament and the Separation of Powers

The examination shall test the candidate's thorough understanding of:

- The doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty as expounded by Albert Venn Dicey, namely that Parliament possesses the legal authority to make or unmake any law whatsoever, and that no person or body may override or set aside legislation passed by Parliament

- The principle that no Parliament may bind its successors, and that any Act of Parliament may be expressly or impliedly repealed by a subsequent Act

- The relationship between Parliamentary sovereignty and the rule of law, including the paradox that whilst Parliament may legislate without legal restraint, it operates within a framework of constitutional conventions and political accountability

- The distinction between legal sovereignty (vested in the King in Parliament) and political sovereignty (vested in the electorate)

- The limitations upon Parliamentary sovereignty arising from membership of international organisations and treaties, whilst recognising that Parliament retains the ultimate legal power to withdraw from such obligations

- The challenges to pure Parliamentary sovereignty posed by devolution, the Human Rights Act 1998, and principles of European Union law during the period of membership

- The principle that courts must give effect to Acts of Parliament regardless of their content, save where Parliament has expressly granted courts power to disapply legislation

- The supremacy of primary legislation over secondary legislation, and the ability of courts to quash secondary legislation which exceeds the powers granted by the enabling Act

- The separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers within the British constitution

- The legislative function of Parliament: the passage of primary legislation through both Houses, the role of Royal Assent, and Parliamentary sovereignty over lawmaking

- The executive function exercised by His Majesty's Government: the implementation and administration of laws, the exercise of Royal Prerogative powers, the formulation of policy, and accountability to Parliament

- The judicial function exercised by the courts: the interpretation and application of legislation, the development of common law, the review of executive action, and independence from political interference

- The overlaps and interactions between the three powers in the British system, including the historical role of the Lord Chancellor across all three branches

- The reforms introduced by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 to enhance separation of powers, including the creation of an independent Supreme Court and changes to the office of Lord Chancellor

- The accountability of the executive to the legislature through mechanisms including parliamentary questions, debates, select committees, votes of no confidence, and the convention of ministerial responsibility

- The independence of the judiciary, including security of tenure, immunity from suit for judicial acts, prohibitions on parliamentary criticism of judicial decisions in pending cases, and the separate administration of the courts

- The sub judice rule preventing parliamentary discussion of matters under active consideration by the courts

- The principle that judges may not sit in the House of Commons but that senior judges historically sat in the House of Lords, and the reforms limiting judicial membership of the upper house

- The role of the Attorney General and Solicitor General as law officers straddling the executive and legal systems

- The constitutional prohibition on the monarch refusing Royal Assent to legislation passed by both Houses of Parliament

- The conventions preventing the monarch from acting independently in political matters without ministerial advice

- The limitation of judicial power to interpret legislation in accordance with parliamentary intention whilst lacking power to strike down primary legislation as unconstitutional

- The development of judicial review as a mechanism for scrutinising executive action whilst respecting Parliamentary sovereignty

- The Carltona principle permitting civil servants to exercise ministerial powers without specific delegation

- The justiciability of certain exercises of Royal Prerogative and the expansion of judicial oversight of executive action

- The principle that Parliament may legislate to overturn judicial decisions it disagrees with

- The constitutional implications of the prorogation of Parliament, as examined in R (Miller) v The Prime Minister (2019)

- The relationship between Parliamentary privilege and judicial authority, including the exclusive cognisance of each House over its internal proceedings

3. Ability to Read and Comprehend Legislation

The examination shall test the candidate's ability to:

- Accurately read and interpret the text of Acts of Parliament, including all sections, subsections, paragraphs, and sub-paragraphs

- Understand the structure of legislation, including long titles, short titles, commencement provisions, definitions sections, substantive provisions, schedules, and extent clauses

- Distinguish between primary legislation (Acts of Parliament) and secondary legislation (statutory instruments, orders, regulations)

- Interpret definitions sections and apply defined terms consistently throughout a legislative text

- Recognise and apply the principle that definitions marked "unless the context otherwise requires" may have different meanings in different sections

- Understand the use of interpretation sections and general interpretation provisions

- Apply the rules of statutory interpretation, including the literal rule, the golden rule, the mischief rule, and the purposive approach

- Recognise the presumptions applied in statutory interpretation, including the presumption against retrospective effect, the presumption of mens rea in criminal offences, and the presumption that Parliament does not intend to violate international law

- Utilise intrinsic aids to interpretation, including long titles, preambles, headings, marginal notes, punctuation, and schedules

- Understand the limited circumstances in which extrinsic aids such as Hansard may be consulted following Pepper v Hart (1993)

- Identify whether provisions are mandatory (using "shall" or "must") or permissive (using "may")

- Understand the effect of words such as "including", "means", "means and includes", and their impact on the scope of definitions

- Recognise when legislation creates offences, including the identification of actus reus, mens rea, defences, and penalties

- Identify who bears the burden of proof in establishing defences or exceptions

- Understand provisions creating civil liability, duties, powers, and immunities

- Interpret penalty provisions, including maximum sentences, fine levels, and alternative sentences

- Recognise commencement provisions and determine when legislation enters into force, including provisions for commencement by order

- Understand transitional provisions, savings provisions, and their effect on pre-existing rights and obligations

- Identify which parts of an Act extend to England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland respectively

- Recognise Henry VIII clauses granting ministers power to amend primary legislation by secondary legislation

- Understand amendments to existing legislation, including textual amendments, substitutions, insertions, and repeals

- Follow amendment trails where legislation has been amended multiple times by subsequent Acts

- Identify implied repeals where later legislation is inconsistent with earlier legislation

- Understand schedules, their relationship to sections, and their legal effect

- Interpret tables, formulae, and technical appendices contained in schedules

- Recognise territorial extent provisions and their implications for the geographical application of law

- Understand provisions made "subject to" other provisions and the hierarchies this creates

- Interpret time limits, including the use of "within", "not later than", "before", and "after"

- Calculate periods expressed in days, months, and years, applying the Interpretation Act 1978

- Understand references to "financial year", "tax year", "calendar year", and other temporal periods

- Recognise and interpret deeming provisions which create legal fictions

- Understand provisions operating "notwithstanding" other laws and their effect in displacing general rules

- Identify provisions that apply "for the avoidance of doubt" or "without prejudice to" other provisions

- Recognise when provisions are severable and when they are interdependent

- Understand the effect of definition sections referring to other Acts

- Interpret provisions incorporating other legislation by reference

- Recognise skeleton legislation and the extent to which detail is left to secondary legislation

- Identify provisions requiring affirmative or negative resolution procedures for secondary legislation

- Understand the use of examples and illustrations within legislative text and their interpretive weight

- Read legislation in conjunction with relevant case law interpreting its provisions

- Identify ambiguities, lacunae, and potential conflicts within legislative texts

4. Capacity for Logical Reasoning and Analysis

The examination shall test the candidate's capacity to:

- Construct valid deductive arguments from general principles to specific conclusions

- Identify logical fallacies including ad hominem, straw man, false dichotomy, slippery slope, appeal to authority, appeal to emotion, circular reasoning, hasty generalisation, and post hoc ergo propter hoc

- Distinguish between necessary and sufficient conditions in causal relationships

- Apply modus ponens (if P then Q; P; therefore Q) and modus tollens (if P then Q; not Q; therefore not P) in logical reasoning

- Recognise valid and invalid syllogistic forms

- Distinguish between correlation and causation in evaluating evidence

- Identify hidden assumptions and unstated premises in arguments

- Evaluate the strength of inductive reasoning and generalisations from particular instances

- Assess the validity of analogical reasoning and identify relevant similarities and differences

- Apply principles of formal logic, including conjunction, disjunction, negation, implication, and equivalence

- Construct and evaluate conditional statements and understand their contrapositives

- Recognise tautologies, contradictions, and contingent statements

- Apply the laws of non-contradiction and excluded middle

- Evaluate chains of reasoning for internal consistency

- Identify category errors and type mismatches in reasoning

- Distinguish between semantic and syntactic ambiguity

- Recognise equivocation and the inconsistent use of terms within arguments

- Evaluate probability and statistical reasoning, including base rate fallacies and misunderstanding of conditional probabilities

- Assess the reliability and relevance of evidence presented in support of claims

- Distinguish between deductive certainty and inductive probability

- Recognise confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, and other cognitive biases affecting judgment

- Apply Occam's Razor and principles of parsimony in evaluating competing explanations

- Evaluate reductio ad absurdum arguments demonstrating the falsity of propositions by deriving contradictions

- Assess the strength of arguments from authority based on relevant expertise

- Recognise the distinction between epistemic and aleatory uncertainty

- Apply principles of proportionality in evaluating the relationship between means and ends

- Evaluate counterfactual reasoning and hypothetical scenarios

- Assess arguments concerning necessity, possibility, and impossibility

- Recognise the burden of proof and its allocation in different contexts

- Distinguish between proof, evidence, and mere assertion

- Evaluate the coherence of conceptual frameworks and theoretical structures

- Apply principles of non-contradiction to identify inconsistent policy positions

- Assess the transitivity of relationships and preferences

- Recognise and evaluate dilemmas, trilemmas, and impossible combinations of desiderata

- Apply mathematical reasoning to policy problems, including cost-benefit analysis

- Evaluate the internal consistency of legislative schemes

- Identify unintended consequences and perverse incentives created by rules

- Assess the practical enforceability and administrability of proposed measures

- Recognise the distinction between de jure and de facto situations

- Evaluate the relationship between abstract principles and concrete applications

- Apply reasoning by cases to exhaust logical possibilities

- Assess the validity of arguments from precedent and the principle of treating like cases alike

- Recognise distinctions that make moral or legal differences and distinguish them from arbitrary distinctions

- Evaluate the coherence of exceptions to general rules

- Apply principles of justice, including procedural fairness, proportionality, and equality before the law

- Recognise conflicts between competing values and assess methods of resolving such conflicts

5. Proficiency in Written and Spoken English

The examination shall test the candidate's proficiency in:

Written English

- Correct spelling of English words according to standard British orthography

- Accurate use of grammar, including proper sentence construction, subject-verb agreement, correct tense usage, appropriate mood and voice, and proper case

- Correct punctuation, including full stops, commas, semicolons, colons, apostrophes, quotation marks, hyphens, dashes, parentheses, and brackets

- Accurate use of capitalisation according to standard conventions

- Proper paragraph structure with clear topic sentences and logical development of ideas

- Coherent organisation of extended writing with introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions

- Appropriate register and tone for formal parliamentary and legislative contexts

- Precise vocabulary with words used according to their accurate meanings

- Avoidance of ambiguity, vagueness, and imprecision in expression

- Clarity of expression enabling a reader of ordinary intelligence to comprehend the meaning without undue difficulty

- Logical progression of ideas with appropriate use of transitional words and phrases

- Ability to write concisely without sacrificing necessary detail or clarity

- Ability to write at length when thoroughness requires extended treatment of a subject

- Correct use of homophones and commonly confused words

- Accurate use of articles (definite and indefinite) according to English conventions

- Proper formation and use of comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs

- Correct use of prepositions and understanding of prepositional phrases

- Accurate formation of plural nouns, including irregular plurals

- Proper use of possessive forms

- Correct formation and use of verb tenses, including perfect and progressive aspects

- Accurate use of modal verbs and understanding of distinctions between shall, will, should, would, may, might, can, could, must, and ought

- Proper use of subjunctive mood where appropriate

- Correct formation of conditional sentences

- Accurate use of relative pronouns and construction of relative clauses

- Proper use of conjunctions (coordinating, subordinating, and correlative)

- Ability to construct complex sentences with multiple clauses whilst maintaining clarity

- Accurate use of direct and indirect speech

- Proper citation and quotation conventions

- Ability to summarise complex material accurately and fairly

- Ability to paraphrase without distorting meaning

- Recognition and correction of common errors including sentence fragments, run-on sentences, comma splices, dangling modifiers, misplaced modifiers, and faulty parallelism

- Understanding of formal written conventions inappropriate to use in legislative or parliamentary contexts, including contractions, colloquialisms, slang, and overly casual language

- Ability to write persuasive arguments with appropriate structure and evidence

- Ability to write analytical prose examining issues from multiple perspectives

- Ability to draft clear definitions suitable for legislative purposes

- Ability to identify and eliminate redundancy and verbosity whilst retaining necessary precision

- Understanding of the distinction between restrictive and non-restrictive clauses and appropriate punctuation thereof

- Ability to maintain consistency in terminology, tense, and person throughout a document

Spoken English

- Clear articulation and pronunciation of English words according to Received Pronunciation or other widely intelligible British accent

- Appropriate volume and projection of voice for addressing assemblies

- Proper pacing of speech, neither excessively rapid nor unduly slow

- Effective use of pauses for emphasis and comprehension

- Appropriate intonation and stress patterns conveying meaning accurately

- Fluency without excessive hesitation, repetition, or filler words

- Accurate spoken grammar corresponding to written standard English

- Appropriate vocabulary for formal parliamentary debate

- Ability to speak extemporaneously on complex subjects with coherence and organisation

- Ability to formulate and articulate arguments clearly in real time

- Ability to respond to questions and interventions without undue confusion

- Appropriate register and formality for addressing the House of Commons

- Understanding of parliamentary conventions regarding forms of address, including references to "Honourable Members", "the Honourable Member for [Constituency]", "my Right Honourable Friend", and prohibitions on direct address between members

- Ability to speak persuasively and with appropriate rhetorical devices

- Clarity of expression enabling listeners to comprehend spoken arguments without undue difficulty

- Ability to summarise complex positions orally with accuracy

- Ability to distinguish one's own views from those being reported or analysed

- Appropriate modulation of tone to convey seriousness, urgency, or other emotions without descending into theatrical excess

- Ability to maintain composure and clarity when speaking under pressure or interruption

- Understanding of when to yield the floor and when to persist in making a point

- Ability to pose clear, direct questions

- Ability to answer questions directly without evasion whilst providing necessary context

- Avoidance of unintelligible mumbling, slurring, or excessive rapidity of speech

- Ability to project confidence and authority appropriate to the parliamentary setting

- Understanding of the conventions regarding sedentary remarks and interventions

- Ability to conclude remarks within allocated time limits

- Capacity to listen attentively to other speakers and respond substantively to their arguments

Liquid Governance & Decisionmaking

The traditional party structure—endless committee meetings, delegate conferences, byzantine voting procedures—cannot scale beyond a few hundred thousand committed activists. To build a mass-membership movement reaching tens of millions requires rethinking democratic participation from first principles.

The answer lies in direct liquid democracy, enabled by cryptographic voting infrastructure that allows every member to vote on everything whilst permitting those who lack time or expertise to delegate their voting power to trusted representatives.

This is not utopian speculation. Estonia has operated internet voting in national elections since 2005. Switzerland conducts binding referenda on complex policy questions with 80% turnout. The technology exists; what matters is the constitutional architecture surrounding it.

Membership and Voting Rights

Membership is open to any British citizen or resident who meets the entrance requirements previously outlined. Upon acceptance and payment of dues, a member receives cryptographic credentials allowing them to vote in all party decisions. The blockchain records every vote whilst zero-knowledge proofs ensure ballot secrecy—the system can verify that you voted without revealing how you voted. This is not theoretical; zkSNARKs already enable this capability.

Every member holds equal voting power: one person, one vote, regardless of wealth, status, or tenure. A new member paying £1,000 has identical voting rights to a Life Member who contributed £25,000. Money buys access and recognition, not power.

Members vote directly on:

- Constitutional amendments to the party's founding documents and rules. These require a 75% supermajority and minimum 5% turnout of total membership. With thirty million members, that means 1.5 million votes minimum—a threshold ensuring only broadly supported changes pass whilst remaining achievable.

- National leadership elections for Party Leader, Deputy Leader, and the National Executive Board. These use ranked-choice voting with majority runoff, conducted over a two-week voting period. Turnout thresholds of 10% (three million votes) prevent fringe candidates winning on derisory participation.

- Policy platform approval, held twice yearly to ratify the programme developed by the National Assembly's policy committees. A simple majority suffices, but policies failing to achieve 30% turnout are returned for revision—the assumption being that weak turnout indicates unclear communication or insufficient member interest.

- Major strategic decisions such as coalition negotiations, fundamental direction changes, or votes of no confidence in leadership. These are triggered by petition of 2% of membership (600,000 signatures) and require 51% approval with 15% minimum turnout.

- Delegated votes on routine matters including candidate endorsements, budget allocation within approved frameworks, and policy details. Members not wishing to vote on every decision can delegate their vote either generally or by policy area (foreign affairs, economic policy, health, education, etc.) to any other member. Delegations are revocable instantly, and delegates cannot re-delegate—if your chosen delegate abstains, your vote abstains.

This delegation system is where "liquid" democracy gets its name. It flows. A busy surgeon might delegate economic policy to a trusted economist friend, education policy to a teacher they respect, whilst retaining direct voting rights on health policy. A pensioner might delegate all votes to their local MP candidate. A political obsessive might never delegate anything. The system accommodates all preferences.

Crucially, vote delegation is transparent. When you delegate to someone, you can see their voting record and revoke instantly if they betray your trust. This creates powerful accountability—delegates know their delegators are watching. It also enables organic meritocracy; members whose voting records prove thoughtful and principled naturally accumulate delegated authority, whilst those who vote carelessly or corruptly lose it.

The quorum requirements are carefully calibrated. Constitutional changes requiring 5% turnout seem low until you realise that represents 1.5 million people—more than voted for the Liberal Democrats in 2024. Leadership elections requiring 10% mean three million votes, comparable to many national elections. These aren't rubber stamps; they're genuine democratic mandates.

Constituencies and Regions

The party's physical structure is deliberately simple. There are 650 constituencies corresponding to Parliamentary seats, and approximately 12-50 regional clusters grouping related constituencies. Nothing more.

Each constituency has an Association—not a representative body but an administrative one. The Association employs a paid agent who maintains an office, coordinates local activities, manages the candidate selection process, and serves as the point of contact for members in that area. The Association is funded by a per-capita allocation from national dues (say, £200 per local member) plus local fundraising.

Constituency Associations are overseen by a Constituency Committee of seven members elected by local membership for two-year terms. This Committee's role is purely operational: organising social events, vetting new member applications, running street campaigns, booking venues. It has no policymaking authority. Policy comes from the national membership via direct vote.

Regional clusters serve primarily as campaign coordination during elections. A Regional Director—appointed by the National Executive Board and reporting to the Director of Campaigns—ensures that neighbouring constituencies share resources efficiently, coordinates regional media strategy, and resolves disputes between local Associations. Regions have no separate democratic mandate; they're administrative conveniences.

This structure intentionally avoids creating intermediate layers of representation. Traditional parties have ward associations, constituency associations, regional councils, and national conferences—each with their own elections, committees, and opportunities for factional control.

This creates what political scientists call "selectorate problems": tiny groups of activists controlling candidate selection and policy positions wildly unrepresentative of the broader membership.

By flattening the structure and routing all major decisions through direct membership vote, we prevent the emergence of an activist class mediating between leadership and membership.

The National Assembly

Here is where the model departs most radically from tradition. The National Assembly is not a representative legislature but a deliberative mass digital council—a standing body of 650 delegates whose function is to develop policy options for membership approval, not to make final decisions themselves.

Each constituency elects one delegate to the National Assembly via ranked-choice ballot of local members. Delegates serve three-year terms with a maximum of two consecutive terms, preventing the emergence of a permanent political class. Critically, Assembly delegates have no independent voting authority. They cannot bind the party to policy positions. Their role is to research, debate, draft, and recommend—the membership decides.

The Assembly meets quarterly in person and continuously online through a dedicated digital forum. It is divided into twelve standing policy committees matching government departments: Constitutional Affairs, Economic Policy, Foreign Affairs, Defence, Home Affairs, Justice, Health, Education, Environment, Energy, Transport, Agriculture. Each committee consists of 54 delegates (650 ÷ 12) plus appointed expert advisors drawn from academia, industry, and the civil service.

These committees operate as policy workshops. They commission research, hold evidence sessions, debate alternatives, and draft detailed legislative proposals. When a committee believes it has developed a workable policy, it presents the draft to the full Assembly for deliberation and amendment. If the Assembly approves by simple majority, the proposal goes to the membership for ratification.

This is where liquid democracy truly shines. A complex trade policy might receive direct votes from 500,000 engaged members (1.67% turnout) plus another four million delegated votes, for a total of 4.5 million (15% effective turnout). The delegates who accumulated those votes through proven expertise in economics and trade policy voted their conscience, while casual members either abstained or delegated to someone they trusted. The result is both democratic and expert-informed.

The Assembly also functions as an electoral college for certain positions. The Party Treasurer and Nominating Officer—statutory roles required by the Electoral Commission—are elected by Assembly delegates rather than the full membership, on the theory these technical positions require familiarity with electoral and financial law that most members lack. The membership retains the right to dismiss these officers by petition and recall vote, but day-to-day appointments flow through the Assembly.

Finally, the Assembly serves as a check on executive overreach. If the National Executive Board or Political Leadership Team takes an action that 40% of Assembly delegates believe exceeds their authority, they can force a membership referendum on the question. This is the "emergency brake"—used rarely, but powerful when deployed.

The National Executive Board

Day-to-day operation of a thirty-million-member organization requires permanent professional management. The National Executive Board provides this, consisting of 20 members elected by the full membership for staggered three-year terms (one-third elected each year). Candidates for the Board must demonstrate executive experience—they submit CVs and undergo public interviews before the election.

The Board divides portfolios among itself: Chair, Deputy Chair (Operations), Deputy Chair (Political), Treasurer (and two assistant treasurers), General Secretary, and Directors responsible for Campaigns, Communications, Policy Development, Membership Services, Training, Candidate Recruitment, Fundraising, Legal Compliance, and Technology. Additionally, eight Regional Coordinators serve on the Board to ensure geographic representation across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

This Board is not a shadowy oligarchy—it operates in the open. Every Board meeting is recorded and published. Every Board decision is documented with reasoning. Every expenditure above £10,000 requires itemised justification. The Board proposes the annual budget, but the membership approves it by direct vote. The Board recommends operational policies, but major strategic changes require membership ratification.

The Board employs approximately 40 permanent staff at national headquarters: press officers, compliance lawyers, accountants, IT engineers, training coordinators, and campaign professionals. These are career positions paying market salaries, not patronage appointments. The party competes with private industry for talent and must offer competitive compensation.

The Board answers to the membership directly, to the National Assembly as an oversight body, and to three independent committees: Audit & Finance, Ethics & Standards, and Elections & Democracy. These committees are elected separately by the membership, serve five-year non-renewable terms, and have the power to investigate, subpoena documents, and issue binding orders. A member of the Audit Committee cannot simultaneously serve on the Board or in leadership—there is strict separation.

Political Leadership Cabinet: The Public Face

While the National Executive Board runs the organisation, the Political Leadership Team represents it publicly and sets strategic direction. This team consists of the Party Leader, Deputy Leader, Chief Whip (when the party has MPs), and optionally a Shadow Chancellor or other senior figures.

The Leader is elected by all members using ranked-choice voting with majority runoff. Candidates must be nominated by at least 50 Assembly delegates and at 30M scale, 50,000 members from at least 100 different constituencies—preventing fringe candidates whilst ensuring legitimate contenders can run. The Leader serves a three-year term and may be removed by either a 60% no-confidence vote in the National Assembly plus a confirmatory membership referendum achieving 55% support, or by direct membership recall petition signed by 15% of members (4.5 million signatures).

The Leader's powers are substantial but constitutionally limited. The Leader:

- Appoints the Shadow Cabinet and assigns portfolios when in opposition Negotiates coalition terms subject to membership ratification

- Serves as the primary media spokesperson and sets messaging strategy

- Has final authority over the election manifesto, though it must correspond with approved policy platform

- Can dismiss the Chief Whip and override candidate selections in exceptional circumstances.

The Leader cannot unilaterally change party policy, expel members, amend the constitution, or spend beyond approved budgets. These require either Board approval, Assembly consent, or membership vote depending on the matter.

The Deputy Leader assumes leadership duties if the Leader is incapacitated and serves as chair of campaign strategy. The Chief Whip manages parliamentary discipline when the party has elected MPs, ensuring voting coordination and enforcing the manifesto commitments.

This separation between executive management (Board) and political strategy (Leadership Team) prevents any single person from dominating all aspects of the party. The Leader controls messaging and political direction but cannot raid the treasury or rewrite the rules. The Board controls money and operations but cannot set policy or negotiate coalitions. Both answer to the membership and Assembly.

Discipline and Standards: A Four-Tier Court

A party of millions will inevitably contain bad actors: fraudsters, extremists, criminals, and those who simply lack the judgment expected of representatives. The disciplinary system must be robust, fair, and insulated from political manipulation.

- Tier One: Constituency Conduct Panels hear minor infractions—missed dues payments, disruptive behavior at meetings, minor breaches of the membership covenant. These are three-person panels elected by local membership, operating informally with warnings and temporary suspensions as the primary sanctions. Appeals go to the Regional level.

- Tier Two: Regional Standards Tribunals consist of five members: two solicitors or barristers, two Assembly delegates from outside the region, and one independent member from the local community (perhaps a retired magistrate). They hear serious misconduct: financial impropriety, public statements damaging the party's reputation, sustained breaches of the covenant, or candidate misbehavior. They can impose fines up to £10,000, suspensions up to two years, or expulsion. Their proceedings are recorded and published (with personal details redacted where appropriate). Appeals go to National level.

- Tier Three: The National Discipline Court is the party's supreme tribunal for standards cases. It consists of nine members: five King's Counsel or senior judges (retired or serving with permission), two Assembly delegates elected specifically for this role, and two external members appointed by the independent Ethics & Standards Committee. This Court hears appeals from Regional Tribunals, original cases involving national officers or leadership, and constitutional disputes about the interpretation of party rules.

The Court's decisions are binding and final—there is no appeal beyond it except to the civil courts if someone claims a breach of natural justice. The Court meets quarterly and publishes full judgments explaining its reasoning, creating a body of precedent governing party discipline. - Tier Four: The Membership Ombudsman is a single independent officer elected by the membership for a non-renewable seven-year term. Any member can file a complaint with the Ombudsman alleging unfair treatment, corruption, procedural violations, or abuse of power by party organs. The Ombudsman investigates confidentially, can compel testimony and documents, and issues public reports with recommendations. Whilst the Ombudsman cannot overturn decisions directly, their reports trigger automatic review by the National Assembly and often lead to policy changes or disciplinary action against officials.

Certain triggers mandate automatic investigation: any criminal conviction, any bankruptcy or insolvency, any public statement advocating violence or extremism, any credible allegation of sexual misconduct or safeguarding failures involving minors. These are not optional—the system must act swiftly to protect institutional integrity.

This elaborate court structure exists because a mass-membership organisation operating in the public sphere will face constant challenges: infiltration attempts, factional warfare, smear campaigns, and legitimate complaints about misconduct. The system must be seen as fair, independent, and immune to political pressure. That requires professional adjudication, published reasoning, and strict separation from the executive and political leadership.

Financial Transparency at Scale

A party with two million paying members collecting £1,000 annually generates £2 billion in revenue—comparable to a mid-sized corporation. This requires corporate-grade financial controls.

All funds flow through the Community Benefit Society, which maintains segregated accounts:

- one for routine operations (salaries, rent, materials);

- one for campaign expenditure (subject to Electoral Commission limits);

- one for reserves (minimum six months operating costs), and

- one for strategic investments (property, technology infrastructure, long-term projects).

The Board proposes an annual budget which the membership approves by direct vote, typically during the spring policy approval cycle. The budget itemises major expenditure categories—£X million for staff salaries, £Y million for regional offices, £Z million for the general election campaign—and allocates reserves for each. Spending within approved categories requires only Board authorisation; spending beyond categories requires either Assembly approval (if under £1 million) or membership vote (if over £1 million).

Every transaction is recorded in the party's financial system. Every expenditure over £10,000 is published monthly with payee, amount, and purpose. Every donation over £500 is disclosed within seven days, including the donor's name, address, and any conditions attached. This goes beyond Electoral Commission requirements—it's voluntary radical transparency to prevent corruption.

The Audit & Finance Committee reviews all accounts quarterly and publishes an independent report. The Committee has access to everything: bank statements, contracts, emails discussing financial decisions. If it finds irregularities, it can freeze expenditure, dismiss the Treasurer, and refer matters for prosecution. This independent oversight is what prevents a wealthy donor from buying influence—every pound is tracked, every commitment is public.

The party can accept unlimited donations from UK sources but maintains internal policy limits: no single donor may contribute more than 5% of annual revenue (£100 million at £2 billion scale) to prevent dependency on any individual. Donors must undergo the same vetting as members: background checks, source-of-funds verification, public disclosure. Overseas money is prohibited except small personal donations from British expats under £10,000 annually.

This financial architecture is designed for a scale that would terrify traditional parties.

The Conservative Party's annual budget is roughly £40 million; Labour's is similar. A party with £2 billion could field 800 candidates spending maximum amounts, operate 650 permanent constituency offices, employ thousands of professional staff, and still have hundreds of millions for strategic media, opposition research, and institutional development. That level of resource concentration could transform British politics—but only if handled with absolute financial discipline and transparency.

Bills, Not Manifestos Or Policies

Policies are ideas which aren't going anywhere. Manifestos are documents of promises which will be broken. Contracts and covenants have backdoor clauses.

Parliament speaks its will in legislation.

Instead of warring over talking-shop ideas and being a field of policy wonks, write the legislation itself. Campaign on the bills before the civil service even have a chance to water them down. Show the electorate your expertise as parliamentarians before they hire you, and what you're going to pass at 9am on day one.

Extremism is unilateral imposition of one's political will on the electorate. Parliamentary democracy relies on persuading the opposition through argumentation and sentiment to obtain consensus through compromise.

The Left must be won in heart and mind; or at least, be able to live what they had to accept. They do not need to be "beaten" in an FA Cup Final. The Left are excellently sensitive pattern recognisers who diagnose problems brilliantly, but are useless at prescribing answers. The right are useless at recognising problems, but are excellent at solving problems with logic and order.

We must work together. We need each other.

The Right must accept they allow things to become stultified and ossified too willingly, as they conserve too stubbornly. The Left must accept their revolutionary changes are all-too-often reckless and destructive.

We can start by bootstrapping how we win the argument and how we persuade the people who don't agree with us – by treating them as people thinking in good faith, and trying to get them what they want, as we implement what we want. Not all their ideas are bad; not all their senses are wrong; and not all the problems they complain about are baseless. Far from it.– it's their answers which are terrible.

Energy

- Position: Kill Net Zero + 26GW nuclear + 5GW tidal + 5GW geothermal + portable hydrogen + oil exports (North Sea, Antarctica)

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: replacing fossil fuels and fracking, nuclear safety technology, funding environmental beautification with oil revenues, unlimited free, cheap energy for working people

Taxation

- Position: taxless society targeting £10 trillion GDP beating Japan.

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: making the working class rich, fast.

Government Spending

- Position: Max state budget of £200bn + nuke all quangoes.

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: directing savings into health, education, and local services.

Health

- Position: Singapore-style hybrid system

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: free-at-point-of-use, no American bankruptcies or price-gouging cartels.

Pensions

- Position: transform to individual wealth funds valued 3x higher on the markets

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: more money for everyone in the last years with stronger protections

Immigration and Borders

- Position: Immediate moratorium + large scale deportation of prisoners & illegals + gently reduce population lawfully by 10 - 20 million.

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: humane repatriation, protecting genuine refugees, phased removal over 20 years as responsible demographic management.

Housing

- Position: Abolish land nationalisation and planning system + remove all regulation + fees + gov loans for deposits.

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: easier for the poor to own a home.

Crime and Policing

- Position: Expand + depoliticise + national inquiry into corruption + fundamental reform.

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: safety for the vulnerable, faster justice for women and minorities.

Justice System

- Position: Abolish Supreme Court & political judges + double prisons + sweeping reform of court system

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: stronger victim support, maintained legal aid, anti-corruption.

Education

- Position: Grammar school in every working class town, individual AI-assisted homeschooling + social hubs for arts and sports

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: massively expanded access to education for poor children, more time with family

Higher Education and Skills

- Position: 2 years national service = free degree + deradicalise + abolish junk degrees

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: no more top-up fees

Transport

- Position: portable hydrogen fuel infrastructure + electric vehicles + cheaper trains

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: sci-fi cheap, clean from A-B

Welfare

- Position: ponzi model was broken by the Pill, made worse by "fixing" it via mass immigration and is unsustainable + limit to 6 months citizens only + retraining

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: not removing the whole social safety net

Families and Childcare

- Position: family first in everything + abortion reform + elderly support

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: support for low-income families, motherhood, parental leave, AI schooling and remote work

Environment

- Position: beautification + sovereign oil wealth fund

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: animal rights, tidal and geothermal, nature protections, even stronger position on protections

Technology and Digital Life

- Position: rapid rollout of multi-terabit fiber to every building in the country + replace civil service with AI + abolish ofcom / license fee / mass surveillance

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: hi-tech government, strict protections, civil liberties

Defence

- Position: heavy rearmament + £150 billion budget focusing on rebuilding the Navy

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: veteran help, anti-Russia/China sentiment, humanitarian deployments

National Security

- Position: border strictness + expulsion of domestic jihadists + Chinese espionage

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: civil-liberties, anti-radicalisation, intel service accountability

Constitutional Reform

- Position: denounce EHCR / internationalism + free speech act + new unity parliament + devolved parliaments to regional upper houses + abolish councils

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: protecting rights, direct democracy, cheaper local services

Foreign Policy

- Position: moratorium on foreign aid + denounce treaties overriding domestic law + withdrawal from military theatres

- Negotiate consensus with the Left via: no more wars, less fractious relationship with the EU

Seat Targeting & Cartel Game Theory

The mathematics are unforgiving. You need 326 seats to form a government, 325 to have the largest single party. With 800 candidates and £29.3 million in potential spending power across all 543 English constituencies, the question becomes: where do you aim the weapon?

The Restorationist has covered these strategy topics in detail previously:

First-past-the-post rewards concentration, not dispersion. The Colonel Blotto principle applies with surgical precision here: spreading resources evenly across all 650 seats guarantees defeat. A party winning 35% of votes in the right 326 constituencies governs; a party winning 45% spread thinly across all 650 sits in opposition with nothing. Geographic efficiency trumps popular support every single time.

The targeting calculation starts with constituency classification. Safe Labour seats with 15,000+ majorities receive zero investment beyond the £500 deposit. Hopeless Tory strongholds in the Home Counties get the same treatment: deposit only, no campaigning, no candidate quality, no leadership visits. These 500-odd constituencies are write-offs. Our candidates there are voting fodder, warm bodies holding the party line when called.

The battle occurs in roughly 150 marginal constituencies where previous majorities sat under 5,000 votes. Here's where the 80-20 Pareto principle bites: 80% of your £29.3 million—call it £23 million—should concentrate on these 150 seats. That's £153,000 per marginal constituency, allowing maximum candidate spending of £20,000 plus substantial local infrastructure, targeted advertising, and ground game operations.

But which 150?

The MRP models and hierarchical Bayesian analysis come into play, identifying where our six elements create natural advantages. Constituencies with strong business communities might respond to our economic doctrine. Areas with high concentrations of tradespeople match with our membership requirements—these voters understand merit-based gatekeeping. University towns could resist, but post-industrial areas burned by deindustrialisation might prove fertile ground for constitutional reform messaging.

Our publication becomes the viability signal. When voters in a marginal seat see sophisticated policy analysis rather than populist sloganeering, it triggers tactical voting in our favour. The institutional backing—a properly registered BenCom with transparent finances and professional governance—separates us from the usual rabble of protest movements. This matters viscerally to British voters who instinctively distrust flash-in-the-pan operations.

The network does the ground warfare. Eight hundred qualified professionals means we can field genuine expertise in every constituency, but our best operators concentrate where it counts. A qualified engineer standing in a post-industrial marginal carries more weight than a career politician parachuted in from London. The £1,500 entrance fee ensures commitment—these candidates have skin in the game and won't flake under pressure.

Yet here's where strategy forks into two distinct paths: the independent assault or the cartel implosion.

The independent route assumes we're strong enough to win 326 seats outright. With perfect execution, targeting the right marginals, and optimal resource deployment, it's theoretically possible. But FPTP's mathematics are brutal. Even with 35% national vote share concentrated efficiently, we might only secure 280 seats. That leaves us as largest party in a hung parliament, forced into coalition negotiations from a position of weakness.

The cartel alternative inverts the game entirely. Rather than viewing other right-wing parties as competitors splitting our vote, reconceptualise them as explosive charges in an implosion weapon, each targeting different voter segments we cannot reach.

Reform pulls disaffected working-class voters who'd never trust a BenCom registered with the FCA. The Christian parties mobilise faith communities your secular constitutional focus won't touch. Homeland captures young eco-nationalists who want radical environmental positions alongside nationalism. The Ulster unionists bring regional identity politics you can't replicate in Northern Ireland.

Under traditional fragmentation, these parties cannibalise each other's votes, handing victory to Labour with 35% pluralities. But a pre-election pact changes the mathematics fundamentally. When eight parties agree to divide the electoral battlefield by comparative advantage, they're no longer competing—they're cooperating to achieve collective critical mass.

The Byzantine Generals Problem explains why this is so difficult: each party fears betrayal. Reform might promise to stand down in Christian-winnable seats, then flood them with candidates anyway. The Heritage Party might agree to northern targeting, then redirect resources to southern seats we're contesting. Without trust, coordination collapses into mutual defection and guaranteed defeat.

Our six elements solve this coordination problem through institutional credibility. The BenCom structure provides transparent governance making secret betrayal harder. The publication creates public commitments costly to reverse—once we've published which seats we're targeting, withdrawal signals weakness. The network of 800 vetted professionals demonstrates serious organisational capacity, not a paper party making empty promises.

The proof-of-work concept applies perfectly. Reform has proven they can mobilise post-industrial voters through years of building in those communities. The Christian parties have demonstrated access to faith networks nobody else possesses. Your proof-of-work is the intellectual infrastructure: the doctrine, the institution, the publication, the examination system. We've built something real while others chase headlines.

A cartel agreement would work like this:

- Constituency allocation occurs six months before the election, announced publicly through all member publications simultaneously.

- Reform takes 200 northern and Midlands seats where they're strongest.

- We take 150 marginals where professional middle-class voters respond to constitutional reform.

- Christian parties get 40 urban constituencies with large faith communities.

- Heritage targets 30 ethnic minority areas.

- Regional parties keep their traditional territories.

The overlaps are minimal because we're accessing different voter pools. A Reform voter in Hartlepool isn't considering the Christian People's Alliance. A professional in Surrey weighing our constitutional platform isn't looking at Heritage. The voter pools segment naturally, making vote-splitting impossible—we're aggregating, not dividing.

Each party campaigns independently in their allocated seats but under a joint shadow cabinet announced before the election. Voters know a vote for any cartel member produces the same government: you handle constitutional reform and institutional design, Reform manages economic policy and immigration, Christian parties oversee family policy and religious freedom, and so forth. The laboratories of democracy concept scales to governance, with each party leading in their proven area of expertise.

The portfolio optimisation becomes elegant. Rather than forcing 800 candidates into seats where half will lose, we concentrate 250 of your strongest candidates in our 150 target marginals plus 100 second-tier targets. The remaining 550 candidates stand in safe opposition seats for visibility and future positioning, but receive minimal resources. Our £23 million concentrates where it matters.

The game theory mechanics invert beautifully. Traditional FPTP punishes cooperation because parties compete for the same voters. But when parties target non-overlapping segments, cooperation becomes positive-sum. Every cartel member's success strengthens the others. Reform winning their 180 seats means 180 seats closer to 326. Us winning our 120 means the combined total reaches critical mass. The Christian parties' 35 seats might seem small, but they're 35 seats nobody else could have won.

The Nash equilibrium shifts entirely. Under fragmentation, each party's optimal strategy is defecting—going it alone to maximise their own seat count. Under the cartel with proper Byzantine fault tolerance protocols, each party's optimal strategy is cooperation because the payoff from collective victory vastly exceeds any individual gain from defection.

Our six elements make us an unusually valuable cartel member. Most protest parties bring voters but lack governing capacity. We bring institutional infrastructure, intellectual credibility, and professional membership capable of actual governance. The doctrine provides policy coherence. The publication offers thought leadership. The network supplies the human capital for ministerial positions and select committee chairs.

The choice is strategic, not ideological. Can we win 326 seats independently? If yes, the cartel dilutes our power unnecessarily. If no—and the mathematics suggest probably no on first attempt—then the cartel transforms likely defeat into possible victory.

The targeting doctrine remains identical either way: concentrate resources on marginal constituencies where investment changes outcomes, write off safe seats as lost causes, maintain presence everywhere for legitimacy but spend nothing where spending achieves nothing.

The Colonel Blotto principle applies whether you're deploying independently or as part of coordinated implosion.

The difference is scale. Independently, we might optimally target 150 marginals and realistically win 80-100 if everything breaks right. In a cartel, those same 150 targets become part of a 500-seat combined offensive where winning 280 collectively might suffice for coalition government, and winning 350 collectively produces comfortable majority.

The seat targeting strategy, then, is this: