Psychotropic Medication And School Shootings

Could antidepressants trigger school shootings? The hypothesis has biological plausibility—but the most comprehensive data show no correlation. More strikingly, the relationship runs backwards: communities experiencing shootings prescribe more antidepressants, not fewer.

Could SSRI antidepressants or other psychoactive medications contribute to acts of extreme violence, particularly school shootings? The hypothesis, though politically charged and scientifically contested, merits careful examination. Not because the epidemiological evidence supports it—the most comprehensive data suggest it does not—but because understanding the biological plausibility, the limits of correlation, and the actual direction of causation matters for both public health policy and clinical practice.

We might frame a scientifically testable version of the hypothesis thus:

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other activating psychoactives might transiently lower behavioural inhibition in a small, vulnerable subgroup, especially under stress or in early treatment phases—potentially modulating, not causing, rare extreme acts.

This formulation is deliberately narrow, acknowledging both biological plausibility and the vanishingly small absolute risk involved.

What the Data Actually Shows

The most comprehensive examination of mass shooters and psychiatric medication comes from the Columbia Mass Murder Database, the largest systematic collection of its kind. After analysing perpetrators across decades, researchers reported strikingly low lifetime antidepressant exposure among American mass shooters. No elevation existed relative to population baselines. This finding contradicts popular assumption and undermines any simple causative claim.

More telling still is the temporal relationship between school shootings and local prescribing patterns. When researchers examined communities after fatal school shootings using quasi-experimental difference-in-differences methodology, they found youth antidepressant prescriptions increased by 21 to 25 per cent in affected areas, sustained for two to five years following the tragedy. The correlation runs precisely backwards from the implied causal story: shootings drive treatment-seeking behaviour for trauma and grief, not the reverse.

The distinction between mass violence and general violent crime proves crucial here. Swedish registry data following 856,000 SSRI users through within-individual comparison found a modest association between treatment periods and violent crime convictions—but only in those aged 15 to 24, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.4 to 1.75 depending on sex. No significant association appeared in adults over 25. Importantly, the authors cautioned against causal interpretation and noted the violent crimes studied bore no resemblance to mass casualty events. Most involved assaults or robberies, quotidian criminal acts bearing little relation to planned massacres.

Finnish national data paints a different picture still. When researchers matched homicide perpetrators to controls within a larger cohort, benzodiazepines showed the strongest association with violent death-causing. Antidepressants demonstrated only slight elevation, substantially weaker than sedative-hypnotics.

These findings create a puzzle: biological mechanisms suggest plausibility, individual case reports describe temporal relationships between medication initiation and violence, yet population-level data show no systematic link to mass shootings and only modest associations with routine violent crime in young people.

Why the Hypothesis Might Be Plausible

Though epidemiological support remains weak, biological mechanisms offer genuine pathways through which psychotropic medications could theoretically influence behavioural inhibition. Understanding these mechanisms helps distinguish between implausible conspiracy theories and legitimate scientific questions.

Serotonergic modulation of prefrontal control presents the most direct pathway. SSRIs increase extracellular serotonin rapidly, yet therapeutic benefit lags behind by weeks. This delay reflects the time required for autoreceptor downregulation and downstream neuroplastic changes. During this early window, serotonergic signalling exists in a state of dysregulation. The prefrontal cortex, which exerts inhibitory control over limbic emotional responses, depends critically on balanced serotonergic tone. Perturbation during the initiation phase could theoretically reduce impulse control in susceptible individuals.

Akathisia provides perhaps the most compelling single mechanism. This syndrome of inner restlessness and compulsive movement arises from dopamine-serotonin imbalance in striatal circuits. It occurs with SSRIs, though more commonly with antipsychotic medications. The subjective experience combines unbearable internal tension with an inability to feel calm or still. Case reports have long linked akathisia to both suicide and violence, with affected individuals describing the sensation as nearly intolerable, driving desperate acts to escape the feeling.

The risk of manic switching in individuals with undiagnosed bipolar spectrum conditions represents another plausible route. Antidepressant monotherapy can precipitate hypomanic or manic episodes, states characterised by disinhibition, grandiosity, impaired judgement, and sometimes aggressive irritability. A young person with subclinical bipolar traits, treated for depression, might experience activation into a state combining reduced impulse control with preserved goal-directed behaviour—a particularly concerning combination.

Dopamine sensitisation offers a fourth pathway. Whilst SSRIs primarily target serotonin, they indirectly influence dopaminergic transmission, particularly in mesolimbic reward circuits. Alterations in reward processing could amplify the salience of grievances or intrusive revenge fantasies, making such thoughts more persistent and emotionally compelling.

Sleep architecture disruption deserves mention as well. Many psychoactives alter REM sleep or produce withdrawal-related rebound effects. Sleep deprivation profoundly degrades prefrontal executive function whilst leaving limbic reactivity intact, a combination known to increase impulsive aggression.

Psychological and Situational Amplifiers

Medication effects cannot be divorced from developmental context and individual vulnerability. Adolescent and young adult brains exhibit incomplete prefrontal cortical maturation, with the very circuits responsible for impulse inhibition and emotional regulation still under construction through the mid-twenties. This developmental window coincides precisely with peak risk for both onset of serious mental illness and perpetration of school violence.

Baseline pathology matters enormously. Depression manifesting with pronounced irritability differs neurobiologically from classic melancholic depression. Individuals with emerging personality disorders, particularly those involving paranoid ideation or narcissistic injury, respond differently to serotonergic perturbation than those with uncomplicated mood disorders. Early psychotic symptoms, sometimes initially mistaken for depression or anxiety, create additional risk.

Environmental triggers cannot be understated. Social rejection, humiliation, romantic disappointment, or perceived injustice—the very experiences known to precipitate school shootings—create periods of heightened emotional arousal. If medication-induced disinhibition exists at all, it would most likely manifest when psychological stress simultaneously taxes impulse control systems.

The medication phase itself matters. If psychotropic-associated violence occurs, it would cluster disproportionately in the initiation period (first two to four weeks) or during dose adjustments and discontinuation. This temporal signature could distinguish pharmacological effects from underlying illness progression.

What a Confirming Signature Would Look Like

If the hypothesis held merit, certain empirical patterns should emerge clearly. Temporal clustering around medication initiation would be essential—violent acts occurring disproportionately within the first month of starting or adjusting psychoactive treatment. We would expect demographic skew towards males under 25, reflecting both neurodevelopmental vulnerability and the known age-sex distribution of violent crime.

Symptom patterns preceding violence should show consistency: reports of agitation, inner restlessness, insomnia, emotional lability, or experiences consistent with akathisia. We might observe similar disinhibition patterns following abrupt cessation, particularly of medications with short half-lives like paroxetine or venlafaxine.

Biomarker evidence could provide supporting data. Positron emission tomography studies of early SSRI exposure show reduced serotonergic prefrontal binding and altered 5-HT1A autoreceptor response. If these neurobiological changes correlated with behavioural disinhibition, it would strengthen mechanistic claims.

Critically, we do not observe these patterns in mass shooting perpetrators. The Columbia database found no elevation in antidepressant use, no clustering around initiation periods, no consistent pharmacological signature. The data signature is absent.

Individual Cases Mislead at Population Scale

Paroxetine (Seroxat in the United Kingdom, Paxil in the United States) stands at the centre of the medication-violence controversy. Study 329, examining paroxetine in adolescent depression, found increased serious adverse events in the treatment group, including conduct problems such as aggression. Clinical trial and pharmacovigilance reviews have noted possible links between this SSRI and violence or hostility in susceptible individuals.

Individual cases gained substantial publicity. A 1998 incident involved a man who began paroxetine shortly before killing family members, resulting in civil damages awarded against the manufacturer. Such cases prove temporally suggestive but scientifically inconclusive.

The problem lies in the base rate. Millions take paroxetine. Violence remains extraordinarily rare. Even if every publicised case represented genuine pharmacological causation—a strong assumption—the absolute risk would remain vanishingly small, unmeasurable in population studies. Case reports illuminate possible mechanisms but cannot establish causation or frequency.

Moreover, paroxetine tends to be prescribed for more severe depression and anxiety, creating confounding by indication. Those receiving this particular SSRI may already be at elevated risk for behavioural problems. Disentangling drug effect from underlying severity proves nearly impossible without randomisation, which ethical constraints prohibit for violence outcomes.

The Fundamental Attribution Problem

People receive psychiatric medication when symptoms worsen. This creates a pernicious circularity in observational research: medication exposure correlates with symptom severity, and symptom severity predicts adverse outcomes. Even sophisticated within-individual designs comparing medicated and unmedicated periods cannot fully escape this trap if treatment decisions respond to time-varying risk factors.

The Swedish team explicitly acknowledged this limitation. Their within-person analysis controlled for stable individual characteristics but could not account for fluctuating severity, concurrent substance use, psychosocial stressors, or other time-varying confounders. Someone starting an SSRI often does so precisely when depression has worsened, when life stress has intensified, or when other risk factors have accumulated. The medication and the underlying crisis coincide temporally but may not be causally linked.

Alcohol and cannabis use, both strongly associated with violence, fluctuate alongside mental health treatment. Young people in crisis often self-medicate with substances whilst simultaneously engaging with formal treatment. Attributing violence to prescribed medication when substance use remains unmeasured introduces systematic error.

The Reverse Causation Evidence

Perhaps the strongest evidence against the medication-causes-violence hypothesis comes from quasi-experimental studies examining prescribing patterns after school shootings. These natural experiments provide what randomised trials cannot: plausibly exogenous variation in treatment exposure.

Fatal school shootings represent discrete, traumatic events affecting entire communities. When researchers compared communities experiencing such tragedies to matched comparison areas, youth antidepressant prescriptions rose sharply in affected locations—by approximately 21 per cent within two years, persisting for five years or longer. This increase reflects post-traumatic stress, grief, and anxiety among students, teachers, and families.

The policy implication proves crucial: if medications caused shootings, we would expect prescribing to decline after such events, as communities recoiled from potentially dangerous treatments. Instead, the opposite occurred. This pattern strongly suggests shootings drive treatment rather than treatment enabling violence.

Why FDA Warnings Confuse the Debate

Following meta-analyses showing increased suicidal ideation in young people taking antidepressants, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning in 2004. This regulatory action, whilst appropriate for suicide risk, has been misinterpreted as evidence of homicidal danger.

The warning addresses internalised self-harm, not externalised violence towards others. Neurobiologically, these behaviours differ, involving distinct neural circuits and psychological processes. Suicidal ideation arises from hopelessness and self-directed aggression; homicidal violence typically involves externalised anger, grievance, and desire to harm others perceived as responsible for suffering.

Post-warning dynamics illuminate unintended consequences. Youth antidepressant prescribing fell sharply, particularly among primary care physicians less equipped to manage complex cases. Subsequent research detected increases in suicide attempts in some populations, suggesting the warning discouraged necessary treatment. This chilling effect demonstrates how regulatory and media attention can reshape prescribing behaviour—with potentially harmful consequences—absent clear evidence of the feared risk.

Psychological Profile of School Shooters

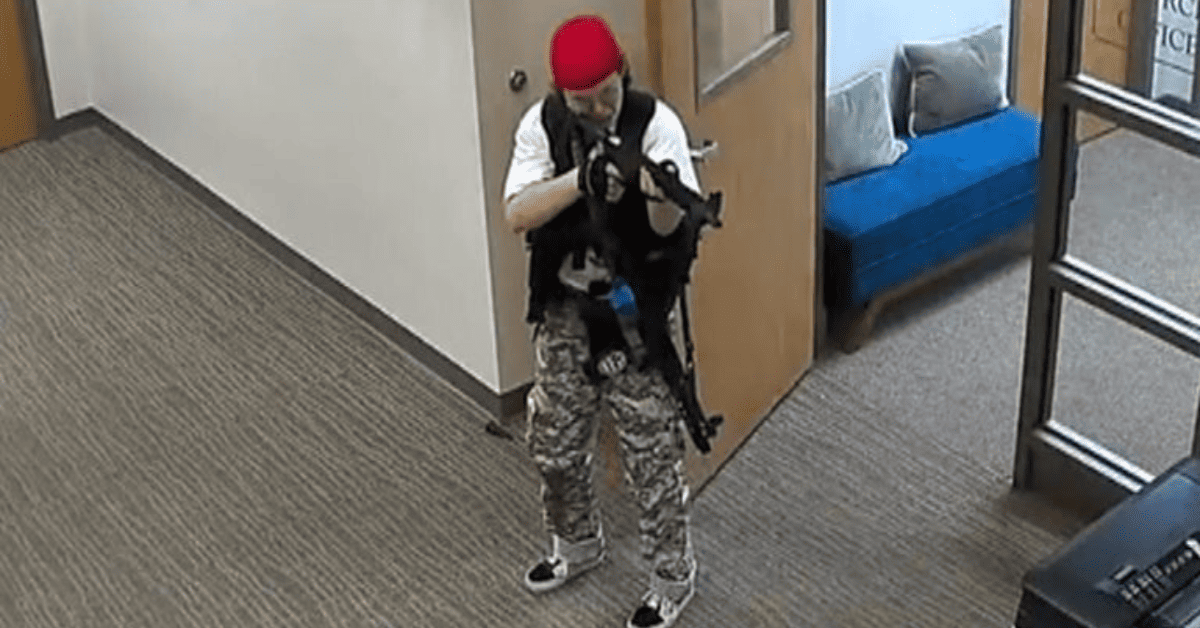

Understanding who commits school shootings clarifies why medication hypotheses fail. The modal perpetrator is male, aged 15 to 25, and critically, not psychotic. Severe mental illness—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychotic depression—appears in only 5 to 10 per cent of cases.

Depression, suicidality, and personality dysfunction appear far more frequently, in perhaps 60 to 80 per cent of cases. These conditions involve narcissistic injury, paranoid interpretation, grievance fixation, and rumination over perceived injustices. The FBI identifies three dominant motivational themes: grievance and revenge (70 per cent), suicidal ideation externalised as murder-suicide (50 to 60 per cent), and quest for notoriety (25 to 30 per cent). These motives overlap and interact.

Early trauma, marginalisation, humiliation, and social isolation feature prominently in perpetrator histories. Crucially, in over 80 per cent of cases, attackers communicated intent beforehand—to friends, online, in journals—behaviour known as "leakage" in threat assessment literature.

About 25 to 35 per cent had some mental health contact before the attack, but few remained actively engaged in treatment. When medication appears in these cases, it exists as background noise—one element among many in complex causal pathways dominated by grievance, access to firearms, social isolation, and failure of intervention despite warning signs.

What We Can and Cannot Conclude

The hypothesis—SSRIs and other psychoactives might transiently lower behavioural inhibition in a small, vulnerable subgroup—remains biologically plausible. Mechanisms exist. Individual cases provide anecdotal support. Modest associations with non-lethal violent crime in young people during treatment periods appear in high-quality registry data.

Yet mass shootings show no such association. The Columbia database, the most comprehensive source, finds no elevation in antidepressant exposure among perpetrators. Communities experiencing shootings show increased subsequent prescribing, the reverse of what a causal relationship would predict. When associations with violence do appear, they remain small, age-specific, and plagued by confounding.

We must distinguish between several possible relationships, each with different policy implications. First, medications might rarely cause violence through direct pharmacological effects. The evidence for this remains weak and limited to non-lethal crimes. Second, medications might be markers for underlying severity, correlating with but not causing adverse outcomes. Third, medications might prevent violence by treating the underlying conditions that genuinely increase risk. The post-shooting prescribing increases suggest communities view treatment as protective, not dangerous.

Clinical and Policy Implications

For clinicians, the data suggest continued vigilance during treatment initiation without unwarranted alarm. Monitoring for akathisia, agitation, and mood destabilisation remains standard practice. Young people, particularly males with irritable depression, personality pathology, or substance use, warrant closer observation. These precautions reflect general principles of good prescribing, not specific fears about mass violence.

For policymakers, the evidence argues against using medication concerns to explain or prevent school shootings. The Columbia data are unambiguous: antidepressant use does not characterise perpetrators. Focusing on pharmaceutical explanations distracts from more productive interventions—threat assessment protocols, reducing access to firearms among high-risk individuals, addressing social isolation and bullying, creating reporting mechanisms for concerning behaviour.

For public discourse, we must separate biological plausibility from empirical support. That a mechanism could exist does not mean it operates at measurable frequency. That individual cases appear temporally suggestive does not establish causation when population-level data show no systematic relationship. Scientific honesty requires following evidence even when it contradicts intuitive stories.

The most important conclusion may be this: school shootings arise from complex interactions between individual psychology, social marginalisation, cultural factors, and opportunity structures. They are not pharmacological phenomena. Young people experiencing depression and suicidality need treatment, not medication avoidance driven by unfounded fears. The evidence, examined comprehensively, supports treatment as part of prevention, not as a hidden cause.