The £100 Million PowerPoint: How Britishvolt Fooled Whitehall

When Britishvolt collapsed without producing a single battery, it exposed how ministers desperate for post-Brexit wins backed a startup with fraud-convicted founders, no technology, and £3 million monthly spending on private jets and yoga classes. The Net Zero phantom company you've never heard of.

Boris Johnson's tweet practically vibrated with optimism. "Fantastic news," the Prime Minister proclaimed in January 2022, hailing Britishvolt as an "EV battery pioneer" and testament to "the UK's place at the helm of the global green industrial revolution." Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng echoed the triumphalism, declaring the planned Northumberland gigafactory would "turbocharge" Britain's electric vehicle ambitions.

Twelve months later, the company entered administration without ever producing a commercially viable battery cell. Most of its 300 employees were made redundant with immediate effect. The £3.8 billion factory existed only as architectural renderings and a partially cleared brownfield site. What should have been Britain's largest private investment since Nissan arrived in 1984 turned into an object lesson in how political desperation trumps commercial due diligence.

The Britishvolt collapse was not merely an unfortunate startup failure. It represented the institutionalised delusion of a government so fixated on post-Brexit industrial victories it suspended elementary judgement. Ministers committed £100 million in public funds to a company riddled with red flags visible from space—a company sources described internally as "a PowerPoint company." They did so whilst the UK's Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) staff raised concerns, credible partners stayed away, and the founders' backgrounds suggested anything but probity.

A Catalogue of Warning Signs

The first alarm should have sounded in December 2020, days after Britishvolt announced its grandiose plans. Co-founder and chairman Lars Carlstrom, a Swedish automotive entrepreneur, resigned when news emerged of his tax fraud conviction in Sweden during the late 1990s. He'd been sentenced to eight months in prison and handed a four-year trading ban, later reduced to conditional sentencing and 60 hours of community service. In 2011, Swedish authorities accused him of acting negligently over an unpaid tax bill for one of his companies.

Carlstrom also had connections to Vladimir Antonov, the Russian businessman and former Portsmouth FC owner who fled English bail whilst facing extradition to Lithuania over allegations of a £250 million fraud at Snoras Bank. Carlstrom had acted as Antonov's representative during an attempted rescue of Swedish car manufacturer Saab. When pressed on his conviction, Carlstrom described it as a "minor allegation" from 25 years ago, insisting he'd always intended to pass on the chairmanship. He quit to avoid becoming "a distraction," taking his shares with him and later establishing Italvolt, a similar battery venture in Italy.

His co-founder, Orral Nadjari, spent most of his career at Swedish corporate bond seller Jool Capital Partner, where he worked both in Gothenburg—playing golf and serving as a goalkeeper for a non-league football team—and later in Abu Dhabi.

In 2021, a subsidiary of Jool had its licence to provide investor services revoked by the Norwegian Financial Supervisory Authority. Neither Carlstrom nor Nadjari brought meaningful battery manufacturing expertise. Neither had successfully delivered a gigafactory anywhere. Yet Whitehall ministers treated their pitch deck as industrial gospel.

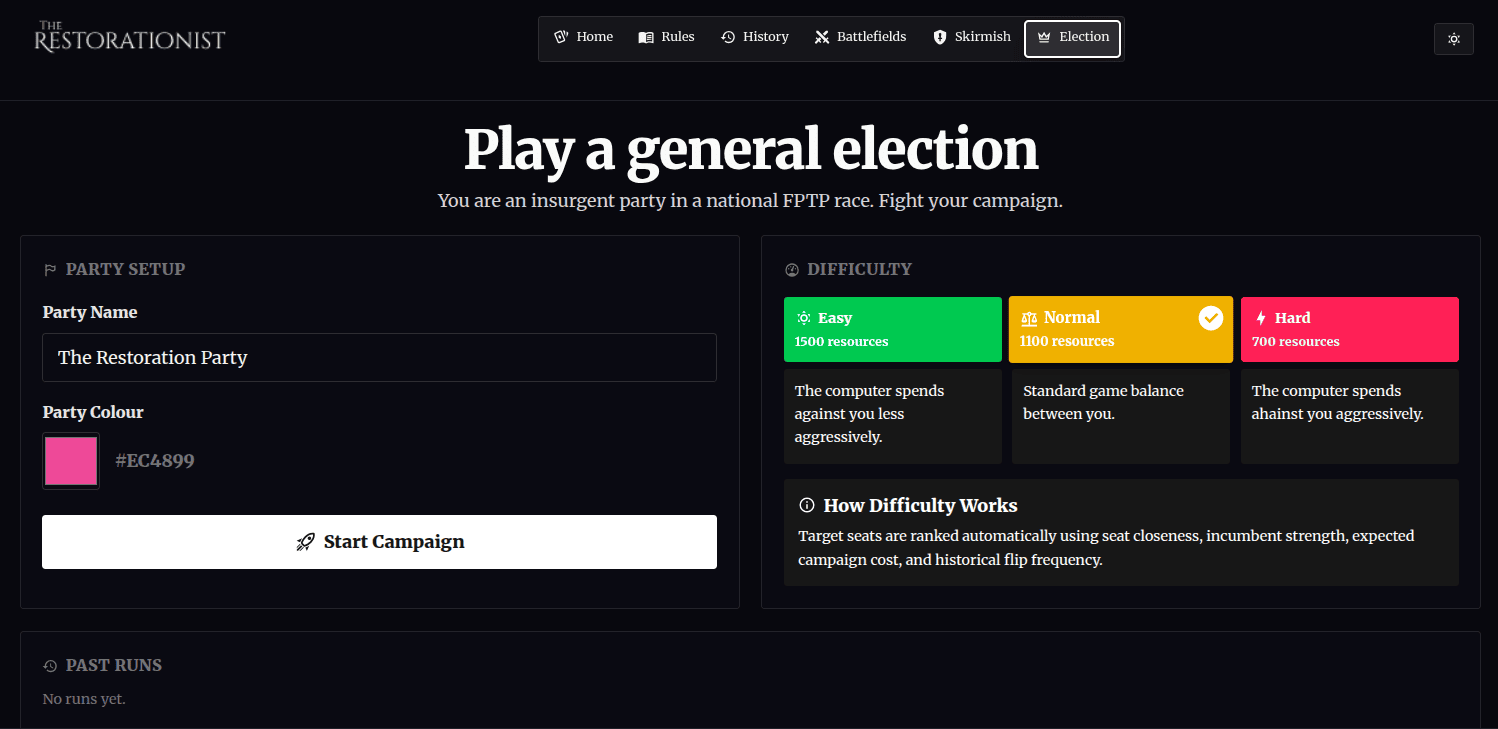

The PowerPoint Company

What precisely did Britishvolt possess when it secured government backing? Not battery intellectual property, as it turned out. The company had signed memoranda of understanding with Lotus and Aston Martin—high-end sports car manufacturers with tiny production volumes—but these were R&D partnerships, not binding supply contracts. Whether prototypes ever reached either manufacturer remains unclear. Former Aston Martin CEO Andy Palmer, who called the collapse an "unmitigated disaster," must have watched with dismay as his erstwhile partners imploded.

The company loudly proclaimed its participation in a consortium to develop solid-state battery technology alongside Oxford University and Johnson Matthey, describing solid-state as "the holy grail of battery solutions" and emphasising "homegrown intellectual property." Preliminary designs for prototyping facilities existed, but sources of funding were "currently being sought." It was industrial vaporware dressed up as cutting-edge technology.

Insiders revealed management consultancy EY was heavily involved in Britishvolt's formation, with the startup sometimes spending more money paying consultants than its own staff. EY, it later emerged, had written the entire business plan from scratch. Three senior Britishvolt executives, including the chief financial officer, were hired directly from EY in 2021. When the company finally entered administration, EY was appointed as—wait for it—joint administrator. The circular arrangement would be comedic if it weren't so expensive.

By September 2022, as fundraising difficulties mounted, Britishvolt was burning £3 million monthly on salaries after hiring almost 300 people whilst still years from generating revenue. The Financial Times documented "profligate spending" including expensive electric company cars, a hospitality suite at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, prolific private jet use, video yoga lessons from a fitness instructor, and top-of-the-range curved 4K monitors. The company rented a serviced office in Mayfair—hardly the postal code of lean manufacturing—and New Field House, a £2.8 million mansion near Blyth complete with swimming pool and gym.

Published accounts covering the 14 months to January 2021 showed an £8.8 million loss, warning of "material uncertainties" over the company's ability to continue as a going concern. Government supporters privately rated Britishvolt's chances of survival at 50-50. Yet the ministerial cheerleading continued.

The Political Imperative

Why did ministers persist? Simple: Britishvolt was all they had. Britain desperately needed battery manufacturing capacity to meet its 2030 ban on new petrol and diesel car sales. Without gigafactories, the entire UK automotive industry faced potential collapse. European Union rules on local content—requiring batteries to be sourced domestically to qualify for tariff-free exports—posed an existential threat. By 2026, the vast majority of a car's value would need to originate in the UK or EU.

Brexit had closed the door to European Investment Bank funding, the kind of development finance that enabled Sweden's Northvolt to raise $8 billion. Northvolt secured $350 million from the EIB alone for its Ett factory, equivalent to more than three times what Britain offered Britishvolt as a percentage of project cost.

Established battery manufacturers looked at Britain's post-Brexit landscape—tariff complications, supply chain fragmentation, reduced access to skilled European labour—and invested elsewhere. Tesla chose Berlin. CATL picked Germany. SK Innovation established three sites in Hungary. LG went to Poland.

Britishvolt offered useless ministers a lifeline: Brexit Britain could attract cutting-edge manufacturing. The "levelling up" agenda demanded high-profile wins in constituencies like Blyth Valley, where Conservative MP Ian Levy faced pressure to deliver tangible economic transformation. The site itself, a former coal power station with deep-water port access and renewable energy connections, genuinely suited a gigafactory. Ministers convinced themselves the location's merits compensated for the company's deficiencies.

Government sources later admitted the decision-making was chaotic. BEIS insiders confessed they weren't working to any particular plan, with one official stating that if Britishvolt could raise capital privately, it should be allowed to do so, whilst stressing that government help remained available to whoever hit construction milestones. This wasn't industrial strategy; it was hope masquerading as policy.

The Slow-Motion Collapse

By summer 2022, reality was overtaking the fantasy. Construction work at Blyth, led by ISG (whose contractor appointment raised eyebrows given that ISG was owned by a Britishvolt shareholder), was suspended in August. Largest shareholder Nadjari quit as CEO amid funding concerns. The Guardian reported the project had been placed on "life support" to cut spending whilst seeking its next funding round. Manufacturing, originally scheduled for late 2023, was pushed to mid-2025—an 18-month delay the company attributed to optimising the build process and sourcing materials "given current supply constraints."

In October 2022, Britishvolt requested a £30 million advance on the promised £100 million government grant. Ministers refused. The company had failed to hit agreed construction milestones needed to unlock the funding. This decision, in retrospect, was the only moment Whitehall applied actual commercial discipline. Britishvolt responded with progressively desperate requests: £11.5 million, then £3 million. Government sources said this sowed "profound seeds of doubt" over viability. Some officials expressed a preference for the company to collapse into administration so "more serious players" could take over the project.

In November, Britishvolt secured short-term emergency funding from mining giant Glencore—less than £5 million, enough for just five weeks. The entire workforce agreed to voluntary pay cuts, with staff receiving 25% or 50% of November salaries. The C-suite worked unpaid in December. By January 2023, three rescue bids were circulating: one from an investment group with links to Indonesia, one from a rump of existing investors desperate to salvage their stakes, and a late entrant described as "a British consortium." None could secure 75% shareholder support.

On 17 January 2023, administrators from EY confirmed what everyone knew was coming. Britishvolt entered administration with debts thought to be as high as £120 million. Around 200 workers were made redundant immediately; 26 remained temporarily to assist with administration. Dan Hurd, joint administrator and EY partner, described the outcome as "disappointing," noting the company had been unable to secure sufficient equity investment for ongoing research and site development.

The Australian Circus

If the Britishvolt saga had ended there, it would merely have been an expensive lesson in industrial policy failure. What followed descended into farce.

In February 2023, Australian startup Recharge Industries, a subsidiary of Scale Facilitation, purchased Britishvolt out of administration for £8.6 million. Its CEO, David Collard, was once PwC's youngest partner at age 32 and had previous ventures including an aborted cannabis business and supplying PPE to New York during the pandemic. Recharge planned to focus initially on energy storage batteries rather than automotive cells, making products available by end of 2025 before targeting high-performance sports cars. The company's strength, Collard claimed, was its relationship with American battery developer C4V, removing the need to develop new technology, plus access to Australian lithium reserves.

The new owner's credibility evaporated rapidly. In June 2023, Australian Federal Police raided Scale Facilitation's North Geelong office, seizing IT equipment as part of a tax fraud investigation related to SaniteX, a business owned by Collard providing services to his other companies. Staff at the firm reportedly hadn't been paid in several weeks. Scale Facilitation denied wrongdoing and pledged full cooperation with authorities.

By August 2023, Recharge had failed to pay the final £8.6 million instalment to complete the Britishvolt purchase, despite an April deadline. The company was being pursued in Australia for a $75,000 debt to Geelong Football Club and monies owed to Deakin University. UK staff hadn't been paid for four months. In January 2024, Collard was arrested in New York on assault and harassment charges relating to an alleged Madison Avenue incident. Australian Federal Police later recommended charges against Collard, fellow director Jimmy Fatone, and accountant Chris Scott over an alleged $126 million tax fraud.

Northumberland County Council, which had extended buy-back clauses to give Recharge time, watched with increasing alarm. No construction resumed. No funding materialised. The gigafactory dream was definitively dead.

From Batteries to Data

In April 2024, the site's denouement arrived. Private equity giant Blackstone Group, through its data centre subsidiary QTS, purchased the 235-acre plot for £110 million to develop what would become one of Western Europe's largest data centres. Plans submitted in December 2024 envisaged up to ten buildings totalling 540,000 square metres, representing £10 billion in investment and creating 1,200 long-term construction jobs.

The transformation was complete: from manufacturing batteries for Britain's automotive renaissance to storing data for hyperscale cloud computing. The jobs would come—albeit a fraction of the 8,000 promised by Britishvolt—but the industrial vision was gone. What should have powered electric vehicles would instead power artificial intelligence workloads for tech giants like Google or Microsoft.

Northumberland County Council, which had purchased the site for £4 million in 2021 before immediately selling it to Britishvolt for the same amount, eventually received £110 million from Blackstone, funds earmarked for investment along the new Northumberland Line. Council leader Glen Sanderson praised the "unique opportunity" whilst local MP Ian Levy spoke of "transformation" and Conservative cooperation. Neither mentioned the gigafactory failure had eliminated thousands of promised manufacturing jobs.

In November 2024, Britishvolt formally entered liquidation. The company existed for less than five years, employed hundreds of people, burned through more than £120 million, and produced precisely zero batteries. ISG, the contractor appointed to build the factory, cited Britishvolt's termination as a contributory factor when it collapsed in September 2024.

The Disastrous Reckoning

The damage extends beyond the financial ledger. Mining conglomerate Glencore wrote off its investment. Engineering contractor NG Bailey reported a £6.8 million hit from its Britishvolt stake, contributing to a £25 million annual loss. Smaller investors saw their holdings evaporate. Most painfully, workers who had relocated to the North East or turned down alternative employment to join a supposed industrial pioneer found themselves unemployed, their skills unused, their careers disrupted.

Britain's automotive industry lost precious time. Whilst ministers courted a fraudulent startup, competitors moved decisively. Chinese-owned Envision AESC expanded its Sunderland facility next to Nissan's plant, but this remains Britain's only significant battery production. The country needs at least five 20GWh gigafactories by 2030 to remain competitive; it has one. BMW announced in October 2022 it would end electric Mini production in Oxford and move it overseas, citing precisely the battery supply concerns Britishvolt was meant to solve.

Parliamentary inquiries followed. The Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee launched an investigation into UK battery supply and manufacturing feasibility. Shadow Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds called the collapse "a symptom of a much wider failure," attributing it to the Conservative government's twelve years of economic mismanagement. Committee chairman Darren Jones argued ministers needed far closer involvement in delivering successful battery manufacturing.

The government's defence was procedural correctness: no grant money was actually disbursed. "We offered significant support through the Automotive Transformation Fund on the condition key milestones—including private sector investment commitments—were met," a BEIS spokesperson explained. "We remained hopeful Britishvolt would find a suitable investor and are disappointed this was not possible."

Technically accurate, morally evasive. The damage wasn't the money paid out but the opportunity cost of backing the wrong horse, the signal sent to credible investors that Britain's industrial strategy operated on wishful thinking rather than rigorous assessment.

Lessons Unlearnt & More Committees

Three years removed from the disaster, its implications remain urgent. Ministers committed substantial political capital to a company whose principals included a convicted fraudster and whose business model consisted of PowerPoint slides and consultant fees. They did so because Brexit had eliminated alternatives and electoral arithmetic demanded Northumberland headlines. The entire apparatus of British government—departments, civil servants, ministers—failed to conduct elementary due diligence or heed internal warnings.

What would competent industrial policy have looked like? Partner with established manufacturers rather than startups. Leverage Britain's genuine strengths—universities like Oxford leading solid-state research, skilled engineering workforce, strategic location—to attract firms with proven manufacturing track records. Provide infrastructure support rather than direct grants to unproven ventures. Accept that not every factory can be British-owned and focus instead on securing employment and supply chain resilience.

Sweden's Northvolt succeeded because it secured binding customer contracts from Volkswagen before seeking billions in financing. It brought in ex-Tesla executives with gigafactory experience. It accessed European Investment Bank funding and navigated EU development finance mechanisms. Britain's exit from those structures demanded even more rigorous commercial discipline, not less.

The Britishvolt site will eventually hum with economic activity as servers process data and algorithms optimise cloud workloads. Blackstone will employ over a thousand construction workers, then hundreds of data centre technicians. The North East will see investment and jobs. But it won't manufacture the batteries Britain desperately needs for its automotive future. Those will come from Germany, Poland, Hungary, China—anywhere Whitehall's industrial fantasies don't override commercial reality.

When historians examine Britain's stuttering response to the electric vehicle transition, Britishvolt will feature prominently: not as a unfortunate accident but as an entirely avoidable catastrophe. Ministers gambled £100 million in political capital, workers gambled their livelihoods, and an entire region gambled on resurrection. They bet it all on a PowerPoint presentation dressed up as industrial renaissance.

Westminster was warned. The red flags were visible, the concerns documented, the due diligence available. They proceeded regardless because admitting Britain lacked viable options felt worse than pretending it had an EV battery pioneer. The gigafactory was always a mirage, shimmering promisingly on the horizon, evaporating upon approach. The question isn't why it collapsed but why anyone believed it would succeed.