The 30-Year Gap: How Britain Failed To Build Nuclear Reactors

Between 1995 and 2025, Britain managed to complete precisely zero nuclear reactors. Not one. This isn't a story about technology or physics—it's about a political class who chose managed decline over difficult decisions, and a civil service that lost the capacity to deliver anything except excuses.

The tediously-named Sizewell B came online on Valentine's Day 1995. At the time, nobody realised they were witnessing the end of an era. The reactor hummed into life, began pushing 1.2 gigawatts into the National Grid, and everyone assumed more would follow. They always had before. Britain had been building reactors since the 1950s—why would we stop now?

Except we did stop. Completely. For thirty years.

Think about what has happened in those three decades. The internet arrived and took over the world. China built entire cities from scratch. We've had eight prime ministers, five general elections, Brexit, a pandemic, and the invention of the smartphone.

In that same period, France built twenty reactors. China built fifty. Even Finland, with all its problems and delays at Olkiluoto, actually finished something.

Britain? We held consultations.

The Arithmetic of Failure

The current situation is simple enough to understand, even for politicians who'd rather not think about it. Britain has nine working nuclear reactors producing about 6.5 gigawatts of power—roughly 15 per cent of our electricity. Most of those reactors will shut down by 2030. Not because of some green crusade or safety panic, but because they're worn out. The graphite cores are degrading, the safety cases are expiring, and you cannot run a nuclear reactor on vibes and optimism.

This is scheduled demolition. We knew it was coming. We've known for decades. The plan, if you can call it that, involves building new capacity to replace the old. Except the new capacity isn't ready. Hinkley Point C was supposed to start generating power in 2025. Then 2027. Now we're looking at 2030 at the earliest, possibly 2031, with costs that have exploded from £18 billion to over £46 billion when you account for inflation.

Meanwhile, electricity demand is rising. Not gently, not predictably, but in great surging waves driven by the AI revolution. Data centres alone could add 26.2 terawatt-hours of demand by 2030—over five times their current consumption. Artificial intelligence isn't just changing how we work; it's creating an entirely new category of electricity demand, one that runs 24/7 and cannot tolerate outages.

So here's where we are: ageing reactors shutting down, replacement projects running years late and billions over budget, and new demand arriving faster than anyone predicted. The gap between what we need and what we're building is not closing. It's widening.

How We Got Here: Privatisation Delusion

The trouble starts, as so much British institutional dysfunction does, in the 1990s. Someone had the bright idea of privatising nuclear power. Never mind nuclear is the definition of long-term strategic infrastructure, with timescales measured in decades and liabilities extending into deep time. Never mind decommissioning costs and waste storage don't fit neatly into quarterly earnings reports. Markets, we were told, would deliver efficiency and innovation.

British Energy was privatised in 1996, with the government keeping the really nasty bits—the decommissioning liabilities, the waste management costs, all the stuff that makes nuclear complicated. The company itself was left with ageing assets and no particular incentive to build new ones. Predictably, it collapsed back into state hands by 2002.

But the lesson learned wasn't "nuclear requires state capacity." The lesson learned was "nuclear is expensive and politically awkward, let's avoid making any decisions." Which brings us to the wilderness years.

The 2000s: A Decade of Strategic Drift

In 2003, the government published an Energy White Paper. It acknowledged nuclear power as low-carbon. It recognised the fleet was ageing. It noted waste issues remained unresolved. And then it proposed... nothing. New nuclear wasn't being recommended, but it wasn't being ruled out entirely either.

Classic British fudge: all the political comfort of deferring a decision, none of the consequences visible until later.

For ten years, Britain drifted. The AGR reactors kept running, ticking down towards retirement like a countdown timer nobody was watching. Sizewell B soldiered on alone, the only pressurised water reactor in the country, a living reminder of the Britain that used to finish things.

During this time, the nuclear supply chain disintegrated. Not dramatically—there was no single moment of collapse—but through slow, steady attrition. Project managers retired and weren't replaced. Specialist welders found work elsewhere. The quality assurance culture, the tacit knowledge of how to build to nuclear standards, the institutional memory of managing major programmes—all of it evaporated.

You can't mothball expertise for a decade and expect to switch it back on. When Britain finally decided to build again, we'd forgotten how. Stuart Crooks, managing director of Hinkley Point C, put it plainly: "Relearning nuclear skills, creating a new supply chain and training a work force has been an immense task."

We're paying first-of-a-kind costs for a reactor design that's already been built in France, Finland, and China, because we lost the capability to do it ourselves.

The Environmental Movement's Blindness

You cannot tell this story without acknowledging the activists. The Soviet-driven Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament spent decades conflating civilian power with weapons programmes, as if Sizewell B and Trident were somehow the same thing. The logic was emotionally powerful but technically illiterate: anything nuclear is dangerous, therefore shut it all down.

Worse were the Greens. The environmental movement should have embraced nuclear as the only proven technology capable of delivering gigawatt-scale, zero-carbon baseload power. Instead, they declared it unnatural. Renewables were pure and good; nuclear was tainted and bad. Never mind the physics. Never mind that no grid anywhere has ever run reliably on wind and solar alone. The aesthetic preference for turbines over reactors became environmental orthodoxy.

Germany's Energiewende is the cautionary tale nobody wants to discuss. Shut down the nuclear plants, build renewables, achieve clean energy nirvana. Except it didn't work. Coal burning increased. Emissions stayed stubbornly high. Energy prices soared. And Germany ended up dependent on Russian gas, with all the geopolitical consequences that entailed.

Britain's Eurocrats looked at this disaster and thought: yes, let's do something similar.

We stupidly legislated net zero in 2019—a legally binding target to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions. And then we failed to build the infrastructure required to achieve it. We have targets. We have roadmaps. We have Green Papers and consultations and stakeholder engagement processes. What we don't have is sufficient zero-carbon baseload power.

Hinkley Point C: The Anatomy of a Disaster

When Britain finally committed to new nuclear, it did so in the worst possible way. Hinkley Point C would be built not through state capacity but through an impossibly complex financing arrangement with EDF, the French state utility. The strike price—£92.50 per megawatt-hour in 2012 prices, guaranteed for 35 years—was eye-watering.

Critics screamed about costs, but what choice was there? Nuclear requires patient capital and long-term certainty. Britain offered neither. We demanded that a single project absorb all the political risk, all the regulatory uncertainty, all the costs of relearning how to build.

When construction began in 2017, completion was expected in 2025. Since then, the project has faced delay after delay. COVID, Brexit, inflation, labour shortages, slow civil construction—the list of contributing factors is long. The cost has climbed from £18 billion to as much as £46 billion in current prices. The completion date has slipped to 2030 or possibly 2031.

This is presented as a failure of nuclear power. It is not.

A government taskforce recently concluded that Britain has become "the most expensive place in the world to build nuclear projects." The problem isn't the technology—it's regulation, procurement, and the complete absence of state capacity to deliver major infrastructure.

Consider the absurdity: Hinkley Point C was required to spend £700 million on fish protection measures that modelling showed would save 0.083 salmon per year. Not 83 salmon. Not 8.3 salmon. Less than one-tenth of one fish annually.

This is what happens when regulatory processes prioritise procedure over outcome, when nobody has the authority or courage to say "this is disproportionate nonsense."

The regulatory system itself has become fragmented to the point of paralysis. A single project can face up to eight different regulators, with no single designated lead, no unified decision-making, and no mechanism to resolve contradictions between different agencies. Each regulator protects its own jurisdiction, interprets standards in its own way, and imposes its own requirements. The result is duplication, delay, and costs that spiral beyond any reasonable proportion to the safety benefits delivered.

The Civil Service, Again

Behind every failed British infrastructure project lies the same institutional rot. HS2, smart motorways, Test and Trace, digital NHS systems—the pattern is consistent. Announce grand ambitions, commission consultants, produce detailed reports, and then fail to deliver anything remotely resembling the original vision on time or within budget.

The civil service, once supposedly the envy of the world, has lost any ability to execute. Permanent secretaries rotate through departments every few years, ensuring nobody develops deep expertise in anything. Policy work is outsourced to management consultancies who bill enormous fees for PowerPoint presentations. Delivery capability has been replaced by contract management, which means government departments can specify what they want but not actually build it themselves.

Building a nuclear programme requires deep technical knowledge, institutional memory, and the political backbone to tell ministers hard truths about timescales and trade-offs. Whitehall has none of these. What it does have is an infinite capacity for process—consultations, impact assessments, stakeholder engagement, regulatory reviews. The motions of governance without the substance.

France succeeded with nuclear because the French state had EDF and the political will to back long-term projects. Britain failed because we dismantled state capacity, embraced market ideology, and convinced ourselves that complex infrastructure would somehow deliver itself if we just wrote the right contract.

The AI Era and the Coming Crunch

Now add artificial intelligence to the mix. The International Energy Agency projects global data centre electricity demand will more than double by 2030, reaching 945 terawatt-hours—equivalent to Japan's entire current electricity consumption. AI is the primary driver of this growth.

Britain is planning nearly 100 new data centres by 2030. Tech giants are queueing up to build AI infrastructure here. The government talks enthusiastically about making Britain a world leader in artificial intelligence. But nobody seems to have done the maths on where the power comes from.

Data centres consume between 10 and 50 times more electricity per square metre than typical commercial buildings. They run 24/7. They cannot tolerate outages. And they're arriving faster than the grid can adapt.

The current plan, insofar as one exists, is wind, solar, and gas. Renewables for the headline emissions figures, gas for when the wind drops. Batteries are mentioned hopefully, but grid-scale storage capable of handling days of low wind and cloud cover remains science fiction at practical scale.

Nuclear would solve this. Small modular reactors, factory-built and standardised, could deliver clean baseload power directly to data centre clusters. The technology exists. Rolls-Royce has a design in regulatory assessment. The economics stack up.

But we won't build them fast enough, because building things fast requires state capacity we no longer possess.

The Promise of Small Modular Reactors

Rolls-Royce SMR has been selected as the preferred bidder to build Britain's first small modular reactors. The design has progressed through regulatory assessment steps ahead of any other SMR in Europe. Each unit will generate 470 megawatts—enough to power a million homes for 60 years.

This is genuinely promising. SMRs offer factory fabrication, standardised components, faster deployment, and lower capital costs than traditional gigawatt-scale plants. They're small enough to replace coal plants on existing industrial sites. They don't require massive cooling water infrastructure. And because they're modular, you can build a fleet rather than suffering through one-off megaprojects.

The government has committed £2.5 billion to SMR development. Three reactors are planned for Wylfa in Wales. The ambition is deployment in the mid-2030s.

Except—and here's the problem—mid-2030s means a decade from now. Meanwhile, most of our existing nuclear fleet retires by 2030. The gap between need and delivery remains.

And even if Rolls-Royce SMR succeeds, it will face the same regulatory maze that has strangled larger projects. The taskforce report identified five systemic failures: fragmented oversight, disproportionate regulation, process-focused culture, weak industry incentives, and excessive risk aversion. These problems don't magically disappear for smaller reactors.

What We Could Have Built

Let's indulge in alternative history for a moment. Suppose in 1995, after Sizewell B came online, Britain had committed to a rolling nuclear programme: one reactor every three years, standardised design, predictable procurement.

By 2025, we'd have ten new reactors operating. Maybe twelve if we'd been efficient.

The capital cost would have been lower—economies of scale, learning curves, established supply chains all reduce unit costs when you build repeatedly. Political risk would have been diffused across multiple projects rather than concentrated in a single do-or-die megaproject. The benefits would have been enormous: three decades of avoided gas imports, lower emissions, genuine energy security.

Instead, we chose drift. We shut down reactors while talking about building new ones. We legislated net zero while defunding the only proven technology capable of achieving it. We created a regulatory environment so complex and risk-averse that it now costs more to build a reactor in Britain than anywhere else in the world.

Where the Blame Lies, Again

There's no one person to blame. It's all of them – again. From the Civil Service, to the Tories, to Labour, to the lefties, to the quangoes. The entire useless and rotten Establishment have failed, and they'd rather we not talk about it.

- The 1990s governments who privatised nuclear without understanding what they were privatising.

- The 2000s governments who chose strategic ambiguity over decision-making, letting a decade slip away while the fleet aged.

- The 2010s governments who pursued one-off mega-deals instead of establishing a proper build programme.

- The activists who made nuclear politically toxic despite it being the only credible path to decarbonisation at scale.

- The civil servants who lost the capability to deliver anything except process.

- The regulators who prioritised procedural perfection over proportionate safety.

The entire political class, Labour and Conservative both, who treated energy security as an opportunity for virtue-signalling rather than a matter of national survival.

The Lights Won't Die —They'll Just Cost More

Britain won't suffer sudden blackouts. That's not how grid failure works in developed countries. Instead, we'll see prices spike when demand exceeds supply. We'll keep coal plants in "strategic reserve" long past their planned closure dates. We'll burn more gas and pretend it's compatible with net zero. We'll build interconnectors to France and Norway and call it energy security while depending on foreign power.

And when the data centres demand more power than the grid can provide, we'll discover that AI leadership requires electricity, and electricity requires the political maturity to build infrastructure twenty years before you need it.

Net zero by 2050 is a fantasy.

Not because the technology doesn't exist—it does. But because delivering it requires a state capable of executing long-term plans, and we no longer have such a state.

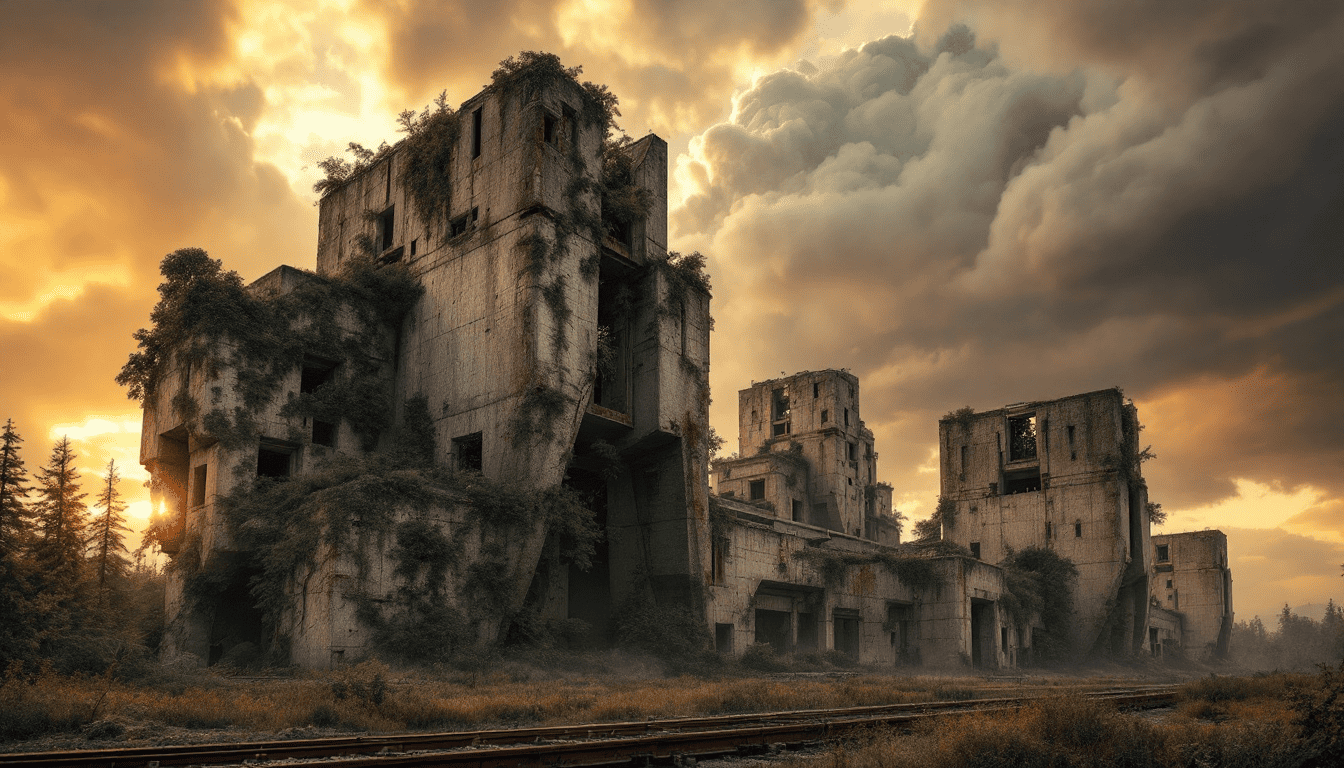

Our Country Is An Energy Museum

Sizewell B still operates, pushing power into the grid, a monument to a Britain that used to finish things. It will probably outlast most of the politicians who've dithered over nuclear policy since 1995. It might even outlast Hinkley Point C's construction timeline.

Somewhere on the Kent coast, the ruins of Dungeness sit as architectural testament to the moment we stopped trying. Dungeness C was never built. The site exists only in planning documents and faded blueprints. Between those plans and the reality of cancelled construction lies the entire story of British energy policy for the past thirty years.

We had the technology. We had the need. We had the money, or at least we would have if we'd started earlier when costs were lower. What we lacked was political courage, institutional capability, and the honesty to admit that some infrastructure cannot be delivered by markets alone.

The thirty-year gap tells you everything you need to know about the Britain we've become: a country that can diagnose problems eloquently, commission reports expertly, hold consultations inclusively, and then fail utterly to build the future we claim to want.