The British Musical Revolution We Never Had

While broadcasters fed you meritless empty diversity trash, a generation of British musicians were quietly producing era-defining cinematic songwriting at the peak of technical skill. They were ignored in favour of cheaply-produced postmodern slop, and are still waiting you to show up.

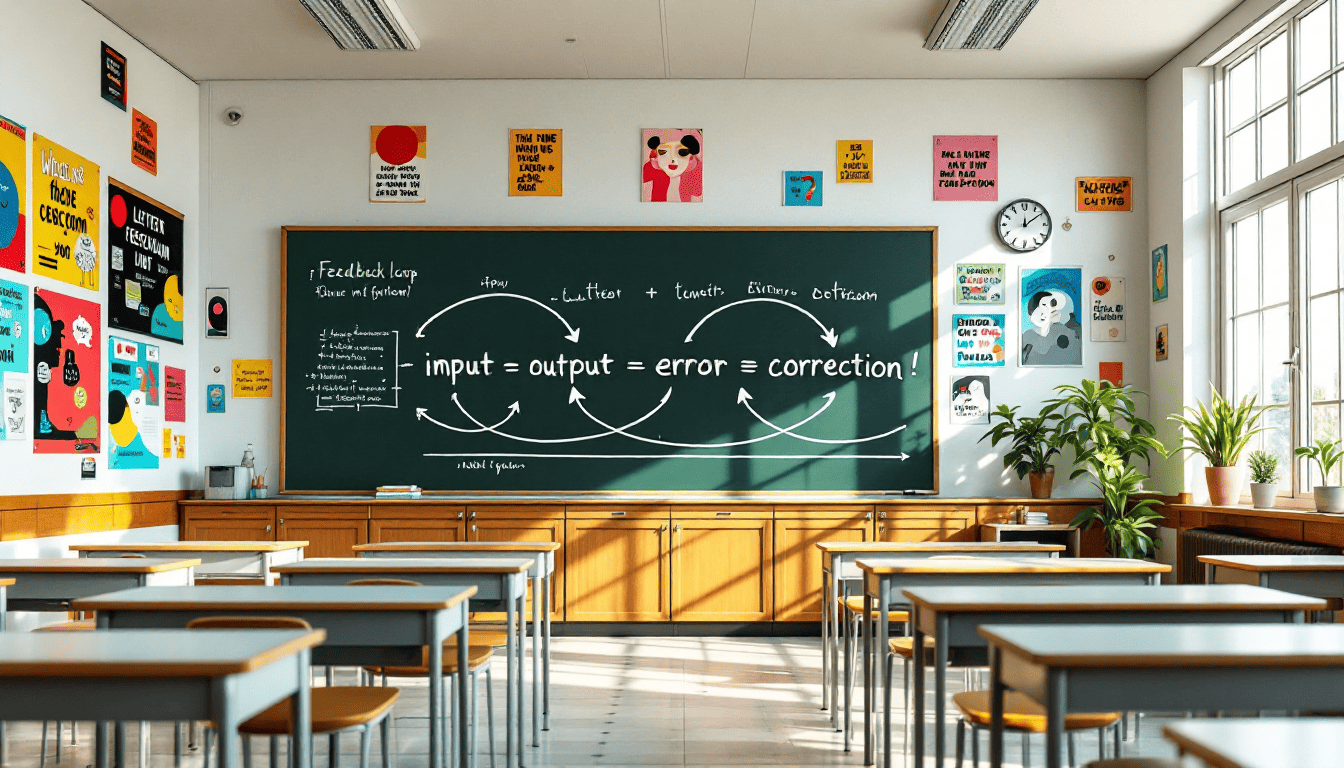

Music of the ancient Greek system has three elements: rhythm, harmony (blended notes, or chords, or Harmonia), and melody. Its quality is determined by how cleverly and emotionally it blends these. Conversely, if it lacks any one of these three elements, it is not music. It is noise. Rap has rhythm and occasionally one of the other two; it is spoken word art, but it is not music, by definition. Dance music and more extreme forms such as Garage have rhythm and some sense of harmony, but no melody, therefore... they are not music. They sound something like music, but they are simulacrum of it.

Something extraordinary happened in Britain over the past twenty years — and almost no one was allowed to see it. While broadcast culture obsessed over junk, quotas, and committee-approved “representation,” an entire generation of musicians were honing their craft in silence: classically trained instrumentalists, cinematic songwriters, and technically elite performers operating far beyond the reach of daytime radio and arts-funded gatekeepers. The revolution did not fail. It was simply never televised.

Only the British can write a dramatic pre-chorus turn like this. or a Boudican anthem like "Into The Fire":

In rehearsal rooms, provincial studios and half-empty venues, Britain produced artists of astonishing fluency. Players capable of orchestral complexity, emotional restraint, and world-class execution, yet they were eclipsed by music designed not to endure, but to comply. What emerged instead of a cultural renaissance was a landscape of algorithmic filler: safe, disposable, ideology-first soundtracks stripped of risk, beauty and ambition.

The result is a lost era hiding in plain sight. Not because it lacked greatness, but because greatness was no longer the metric. And it's time we demanded it back so we can enjoy it.

Is there any better poetic Restoration anthem describing modern melancholy?

I think I'll move 5000 miles

Down the south towards the sea

'Cause the world isn't all just a vampire

England just might be

'Cause it wears me out

Drains the joy

That I swear I had when I was a boy

But maybe that wasn't me

Just a memory

All the time I wasted

Refusing to let you go

From every place I've been to the state I'm in

I needed to let you know

That my mind's made up

When I've had enough of the way that my face turns red

I said my mind's made up

Yeah I've had enough

Oh England get out of my head

Britain shines, even in her ruin and injury. Perhaps even brighter.

The Sound Of British Music

Listen closely, and study. You'll notice something. British music has certain characteristics you cannot find anywhere else.

It is highly dramatic.

It is emotional, sentimental, mood-swinging, and all things we refuse to be in public. Our music is an outlet for the things Victorians frowned on expressing. The more you suppress them, the more intensely they burst out. Think about Bohemian Rhapsody: it's pure melodrama pantomime which makes no sense.

It is a singalong.

Music isn't a private activity – it invites and involves everyone. Britannic songs are group affairs everyone needs to join or be pushed aside. We write music for each other, to sing together, even if we don't join in. What's the one tune everyone knows on guitar and drunkenly sings at BBQs? Wonderwall.

It is the explosive pub brawl.

We all know that hour: 10pm at night and everyone's had too much to drink. Aggressive, difficult, stubborn, emotional, and inflammatory. Provocative. Obstinate. Telling her you love her despite the consequences. Picking a fight even though you love him. Having a quiet cup of tea, humming away. Wanting to put a fist through the window but not doing it. Whistling to the folk song. A tempest of virulent stoic determination waiting to reach out and stir the boiling pot. At the same time Elton was singing Saturday Night's Alright For Fighting, the punks were raging God Save The Queen, The Fascist Regime.

We sing because that's who we are and what we do.

What do the British Army love? A good sing-song and a cup of tea during a fight.

Put simply, our music reflects who we are as a people. It memorialises our character. The British are the music they write. Our songs carry our memory and express our essence, whether we design it that way or not.

The Japanese do not sound like this. Music does not play like this in Equatorial Guinea. Saudi Arabia does not have a football chant tradition. India and China did not birth rock n' roll, augment classical theatre as heavy metal, or consider people national treasures despite them being gay.

The English don't even need the musicians and will just naturally sing because they're together. It's an absolutely extraordinary thing to behold. It's something we just naturally do because it's who we are.

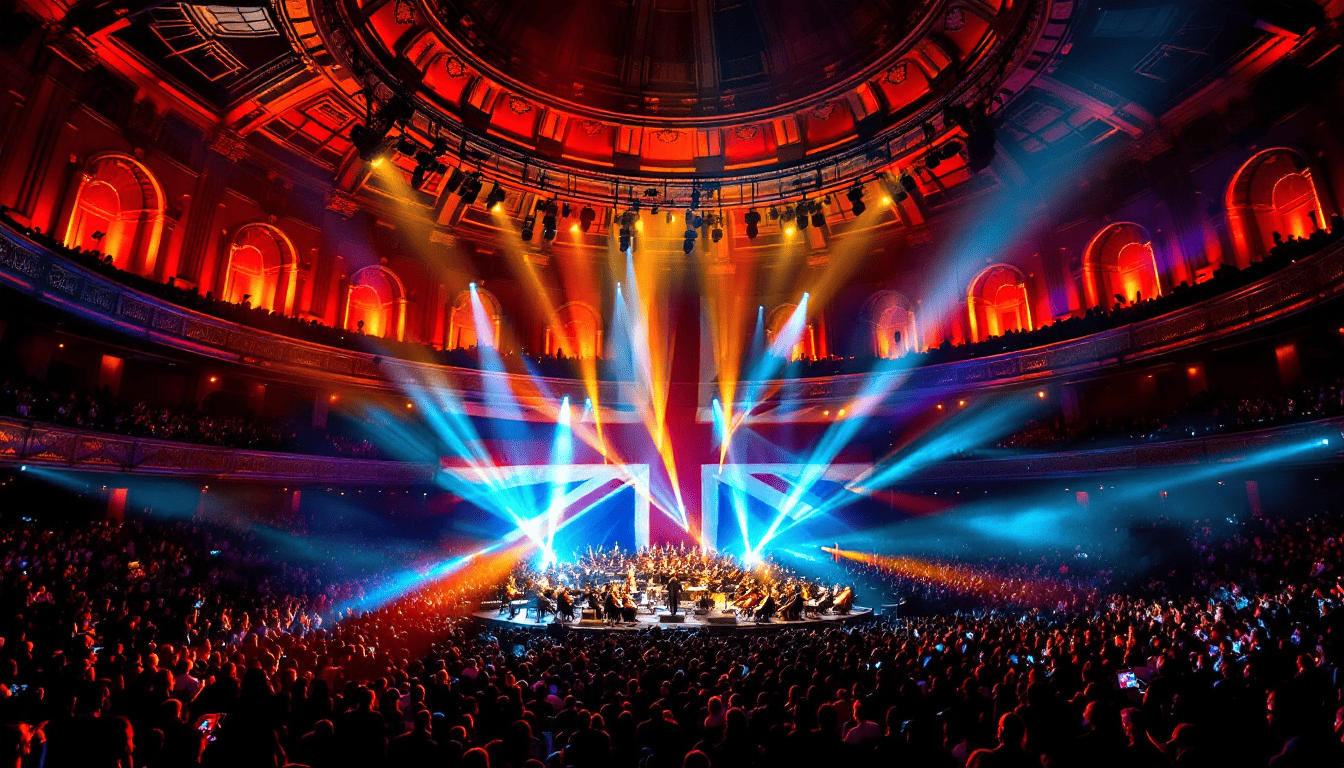

The Royal Albert Hall: Still The World's Best Music Venue

You don't need many words for what two minutes of a video can demonstrate clearly. There is no building on planet Earth which can rival the RAH for musical drama.

Still The Best Guitarists In The World

From basement practice rooms to global stages, Britain has produced some of the most technically daring and influential electric guitarists of the 21st century. We have UK-rooted players who combine relentless discipline with innovative musical voices, often rising from DIY scenes and social-media grind to international renown.

Andy James

Born in Portsmouth, a working naval city with little industry for professional musicians. Largely self-taught, he spent years uploading instrumental demos online while working outside the music industry. His early career was built through persistence on forums, small endorsements and relentless self-promotion before finally breaking through internationally as a solo artist and later joining Five Finger Death Punch.

- https://www.andyjamesguitaracademy.com

- https://www.youtube.com/andyjamesguitaracademy

- https://www.instagram.com/andyjamesguitar/

Olly Steele

Olly is from Sheffield, a city with a heavy industrial decline which also produced acts like Bring Me The Horizon and Arctic Monkeys. He came up through small metal bands before joining Monuments, enduring repeated lineup collapses and financial instability. After leaving the band, he rebuilt his career independently through solo releases and session work.

- https://ollysteele.co.uk

- https://www.youtube.com/c/ollysteele

- https://www.instagram.com/ollysteelguitar/

Sophie Lloyd

Sophie grew up in London and studied popular music performance at BIMM. She spent years performing in small venues and building an online following long before mainstream recognition. Her breakthrough came only after viral guitar videos — a reminder of how difficult traditional industry routes remain in the UK. Yes, she's a little cringe. But she's also excellent at her craft.

- https://www.sophieguitar.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/sophieguitarofficial

- https://www.instagram.com/sophieguitar/

Bartek Dabrowski

Originally from Poland and later relocating to the UK, Bartek built his career as an outsider to the British music industry. Working largely independently, he developed his audience online without label backing. His rise reflects the modern reality of European musicians finding opportunity through the UK’s underground progressive scene.

- https://bartekdabrowski.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/BartekDabrowski

- https://www.instagram.com/bartekdabrowski_official/

Still The World's Best Pianists

Classical music has deep roots across Europe, but British concert pianists — forged in local conservatoires, national competitions, and relentless touring schedules — have helped shape the modern keyboard repertoire. These artists blend technical mastery with interpretive depth, often overcoming financial, educational, or health obstacles on their path to global stages.

Benjamin Grosvenor

Benjamin was born in Southend-on-Sea — not a traditional classical hub. Identified as a prodigy early, he faced intense pressure from childhood, performing internationally before his teens. His challenge was not entry, but survival — avoiding burnout while transitioning from child prodigy to serious adult artist.

- https://www.benjamincrosvenor.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/BenjaminGrosvenor

- https://www.instagram.com/benjamincrosvenor/

Alexander Ullman

Alexander was born in London and trained at the Curtis Institute in the United States after struggling to find equivalent elite opportunities at home. Like many British classical musicians, he left the UK to progress. His career has been shaped by international competition circuits rather than domestic patronage.

- https://www.alexanderullman.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/AlexanderUllman

- https://www.instagram.com/alexanderullmanpiano/

Martin James Bartlett

Martin grew up in Kent and trained at the Royal College of Music. Despite winning BBC Young Musician in 2014, sustained financial support did not follow automatically — a common reality in British classical music. His career has required constant touring and self-funded promotion.

- https://www.martinjamesbartlett.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/MartinJamesBartlett

- https://www.instagram.com/martinjamesbartlett/

Still The Great Orchestral Stars

Away from stadium lights and algorithm-driven fame, Britain continues to produce instrumentalists of extraordinary calibre. Violinists, cellists, flautists and soloists are forged through years of disciplined study, regional youth orchestras, and relentless touring — often with little public recognition. These musicians sustain the backbone of Western classical music, carrying centuries of tradition forward while quietly redefining virtuosity for the modern age.

Jack Liebeck

Jack was born in London and raised in Hertfordshire. His career nearly collapsed early after injury and professional instability before winning the BBC Young Musician competition in 1995. He later rebuilt his reputation slowly through chamber and orchestral work.

- https://www.jackliebeck.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/JackLiebeck

- https://www.instagram.com/jackliebeck/

Tamsin Waley-Cohen

Raised in London within an artistic family, Tamsin nevertheless rejected the standard classical path early on. She has spoken openly about resisting competition culture and rebuilding her career around independent programming and artistic control rather than prestige circuits.

- https://www.tamsinwaleycohen.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/TamsinWaleyCohen

- https://www.instagram.com/tamsinwaleycohen/

Braimah Kanneh-Mason

Braimah was raised in Nottingham in a large musical family educated largely at home. Financial limitations meant instruments were shared and travel was difficult. The family’s success is widely cited as a rare case of working-class access breaking into elite British classical institutions.

- https://kannehmason.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/BraimahKannehMason

- https://www.instagram.com/braimahkannehmason/

Adam Walker

Adam grew up in County Down, Northern Ireland, where access to elite orchestral pathways was limited. He moved to London to pursue professional training and spent years freelancing before securing a permanent role with the London Symphony Orchestra.

- https://www.adamwalkerflute.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/AdamWalkerFlute

- https://www.instagram.com/adamwalkerflute/

Laura van der Heijden

Born in Surrey and raised in the south of England, Laura balanced mainstream schooling with elite musical training. Despite early awards, she faced the familiar post-competition drop-off where funding and visibility sharply decline. Her career has been sustained through international touring rather than UK institutional backing.

- https://www.lauravanderheijden.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/LauravanderHeijdenCello

- https://www.instagram.com/lauravanderheijden/

Xhosa Cole

Xhosa is from Birmingham, a city with deep jazz heritage but limited funding. He spent years playing unpaid sessions and community workshops before wider recognition. His career reflects the grassroots survival model of British jazz.

Alexandra Ridout

Raised in Hertfordshire, Alexandra emerged from the UK youth jazz circuit where competition is fierce and paid work scarce. She built her reputation through small ensembles and session work before wider recognition.

- https://www.alexandraridout.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/AlexandraRidout

- https://www.instagram.com/alexandraridout/

Yussef Dayes

Yussef grew up in South London amid poverty, instability and exposure to violence. Largely self-taught, he avoided formal conservatoire training, instead learning through pirate radio, jam nights and underground venues. His rise mirrors the rebirth of London jazz from non-institutional roots.

- https://www.yussefdayes.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/YussefDayes

- https://www.instagram.com/yussefdayes/

Morgan Simpson

Morgan is from Chelmsford, Essex. He joined Black Midi as a teenager, leaving school early and entering a relentless touring schedule. The band’s early years were marked by exhaustion, financial insecurity and constant pressure before critical acclaim followed.

Still The World's Best Melodic Rock n' Roll Songwriters

From post-industrial towns to major UK cities, these bands emerged not through instant hits but through years of touring, DIY releases and scene persistence. Their melodic rock ethos is rooted in British songwriting traditions — storytelling, grit, reinvention — that resonate far beyond the UK.

Heart of Gold

There comes a time when you must put politics aside, and this band have some of the worst. But when it comes to music, it's the language of the soul, not the bible of political doctrine. Based in the UK and active on the indie rock circuit, they have steadily built a following via EP releases, tours and consistent online content. Their sound blends classic melodic hooks with modern alt-rock sensibilities, often balancing anthemic choruses with introspective lyrics — a signature of contemporary British rock evolution

- https://www.thisisheartofgold.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/HeartOfGoldUK

- https://www.instagram.com/thisisheartofgold/

Deaf Havana

Formed in King’s Lynn, Norfolk — far from the UK industry centres — Deaf Havana endured years of van breakdowns, unpaid tours and lineup changes. Their near-breakup in 2015 forced a reinvention that ultimately saved the band. And they are simply the writers of the finest melodies England has to offer – bar none.

Fightstar

Fightstar formed in London in 2003, initially facing hostility due to Charlie Simpson’s pop background. The band toured relentlessly to prove credibility, often playing to hostile crowds before gaining respect on merit alone.

- https://www.fightstarofficial.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/FightstarOfficial

- https://www.instagram.com/fightstarofficial/

Young Guns

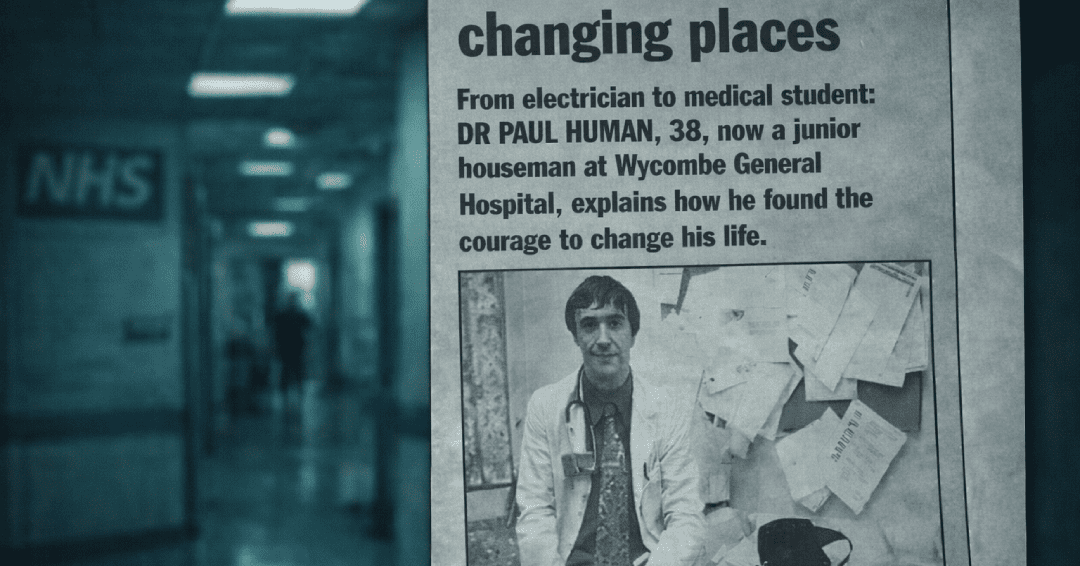

Young Guns originated in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire. Early success was followed by label instability and industry shifts that left the band without support. They survived through independent releases and fan-funded touring.

- https://www.younggunsuk.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/YoungGunsUK

- https://www.instagram.com/younggunsuk/

Mallory Knox

From Cambridge, Mallory Knox faced repeated label collapses and financial uncertainty despite chart success. Their eventual split reflected the brutal economics of mid-level British rock bands.

- https://www.malloryknoxofficial.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/MalloryKnox

- https://www.instagram.com/malloryknox/

Heaven's Basement

Formed in Redcar, Teesside — one of the UK’s hardest-hit post-industrial towns — Heaven’s Basement battled management failures and industry collapse before disbanding despite international touring success.

- https://www.facebook.com/heavensbasement

- https://www.youtube.com/c/HeavensBasement

- https://www.instagram.com/heavensbasement/

Boston Manor

Boston Manor hail from Blackpool, a town marked by economic decline. They rose through DIY touring, self-releasing music while working day jobs, before finally breaking through internationally.

- https://www.bostonmanorband.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/BostonManorBand

- https://www.instagram.com/bostonmanor/

Marmozets

From Bingley, West Yorkshire, Marmozets were a family band that toured relentlessly from their teens. Years of physical and mental burnout culminated in a hiatus before their return.

- https://www.instagram.com/marmozets

- https://www.youtube.com/c/Marmozets

- https://www.instagram.com/marmozetsofficial/

The Struts

Formed in Derby, the band spent years living out of vans while chasing success in the UK — only breaking through after relocating to the United States. Their story is a case study in Britain exporting its own talent.

- https://www.thestruts.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/TheStrutsVEVO

- https://www.instagram.com/thestruts/

The XCERTS

Originally from Aberdeen, Scotland, The Xcerts relocated to Brighton due to lack of opportunity at home. Years of financial hardship and lineup changes preceded mainstream recognition.

Asking Alexandria

Founded in York, Asking Alexandria grew out of internet demos and teenage experimentation. Sudden international fame brought internal conflict, addiction struggles, and multiple lineup crises before stabilisation.

- https://www.askingalexandria.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/AskingAlexandriaOfficial

- https://www.instagram.com/askingalexandria/

Lower Than Atlantis

From Watford, the band spent nearly a decade touring without meaningful financial return. Despite mainstream success, the economics of UK rock forced their eventual split — a familiar industry story.

- https://www.lowerthanatlantis.com

- https://www.youtube.com/c/LowerThanAtlantis

- https://www.instagram.com/lowerthanatlantis/

Royal Blood

Formed in Brighton, Royal Blood emerged during the collapse of guitar-driven radio. Their stripped-back two-piece sound was born partly of necessity — limited resources forcing innovation.

- https://royalbloodband.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/RoyalBloodOfficial

- https://www.instagram.com/royalblood/

Bring Me The Horizon

Originating in Sheffield, the band came from a city scarred by post-industrial decline. Early years were marked by controversy, addiction issues, and extreme touring schedules. Their survival and reinvention into one of Britain’s biggest modern bands is almost unprecedented.

- https://www.bmthofficial.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/c/BMTHOFFICIAL

- https://www.instagram.com/bmthofficial/

We Owe Them A Massive Debt

Listen to what this generation of artists are saying. We've had enough. I can't see your halo falling. I'll walk into the fire. Hold onto your heart. Don't let me drown. England, i can't let you go. They're singing for us; articulating what we all feel.

We've let them down. Nobody invested in them. It's our responsibility and duty. They belong to us, and we belong to them. They're ours.

Book them. Follow them. Subscribe to them. Buy their merch. Visit their websites. Share them. Forward them. Tell people you know.