The Fatal Flaws Of The 80 Year-Old Beveridge Welfare Model

Britain's post-WWII welfare state didn't even make it 20 years before its mathematics collapsed. William Beveridge's arithmetic was a spreadsheet for a world that would vanish within a generation. Today, that system—or what's left of it—resembles a Ponzi scheme.

In 1942, a Liberal economist named William Beveridge sat down to design a system he believed would eliminate poverty in Britain. He was neither a socialist firebrand nor a bleeding-heart idealist—he was a Liberal party technocrat who thought he'd solved a mathematical problem. He imagined temporary unemployment insurance, modest pensions for a few years of retirement, and a safety net for genuine hardship. He calculated everything carefully: how many workers would support how many dependents, how long people would claim benefits, what it would cost.

He was wrong about almost everything.

Not because he was stupid or malicious, but because he built a spreadsheet for a world that would vanish within a generation. Today, that system—or what's left of it—resembles a Ponzi scheme more than social insurance. The numbers don't work. They can't work. And every attempt to fix them creates a fresh crisis.

The World Beveridge Actually Designed For

Picture post-war Britain: bombed-out cities, rationing, a shattered economy trying to rebuild. Beveridge looked around and saw specific, concrete problems. Men returning from war needed work. Families needed housing. Children needed feeding. The poor law system—a patchwork of parish relief and Victorian charity—couldn't cope with industrial-scale poverty.

But here's what Beveridge also saw, and assumed would continue: factories full of employed men, wives at home raising children, families staying together, people dying relatively soon after retirement.

His calculations rested on a particular demographic and social arithmetic.

The technical assumptions were explicit and detailed. Beveridge assumed:

- Near-universal male employment—perhaps 3% unemployment at most, and strictly temporary.

- In his model, a man would work from age 20 to 65, pay National Insurance contributions for 45 years, then retire and die within a decade.

- Birth rates would stay high—three or four children per family, maintaining a fertility rate well above 2.1.

- Stable marriages would remain the norm.

- A cultural stigma around long-term benefit dependency would informally ration claims.

Under these conditions, the mathematics worked beautifully. Lots of workers paying in, few pensioners taking out, and those pensioners not taking out for very long. The system wasn't designed to be generous—benefits were deliberately set at subsistence level to preserve the incentive to work and save privately. It was meant as a floor, not a feather bed.

Beveridge's Arithmetic: The Original Calculations

The genius of Beveridge's design—and its fatal weakness—lay in how precisely it depended on specific demographic ratios remaining constant.

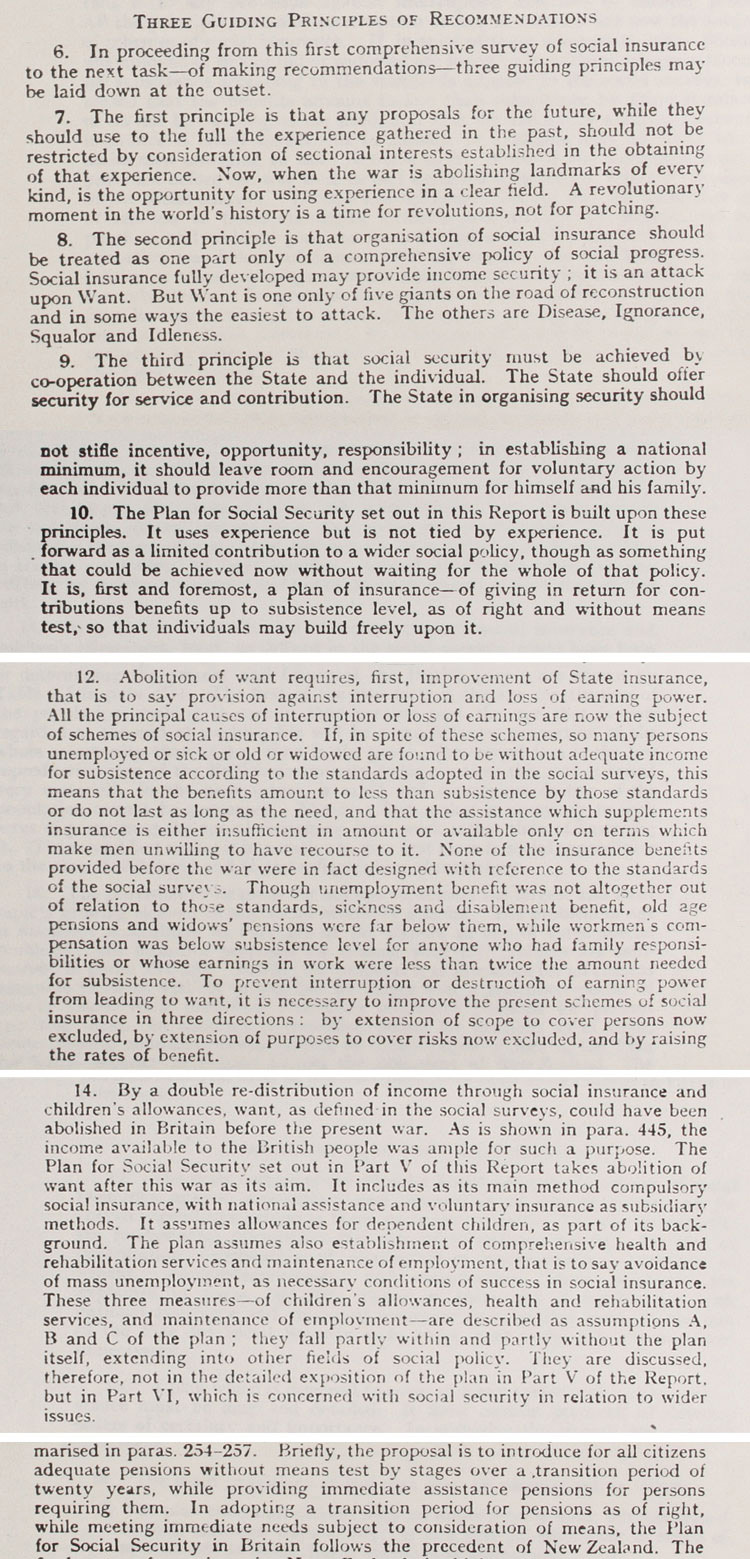

It can be viewed at the National Archives:

Extracts from the Beveridge Report, detailing key aims and vision, November 1942 (PREM 4/89/2)

His model treated the welfare state as an actuarial exercise. Like any insurance scheme, it pooled risk across a population where most people would pay in substantially more than they took out. The temporary claimants would be subsidised by the lifetime contributors.

The dependency ratio was the critical variable. In 1950, there were roughly 5.6 working-age people (ages 16-64) for every person over 65. Beveridge's calculations assumed this ratio would remain stable or improve as post-war economic growth accelerated. More importantly, he assumed the elderly dependency period would remain brief.

Consider the life expectancy data he was working with. In 1942, a man who reached age 65 could expect to live, on average, another 11 years. A woman might reach 13 or 14 additional years. The state pension—set at 65 for men, 60 for women—was designed to cover perhaps a decade of retirement at most. Many workers would die before reaching pension age at all.

This created a favourable equation: 45 years of contributions funding 10 years of benefits.

The mathematics worked even with modest contribution rates. Beveridge calculated the system could function sustainably with National Insurance contributions of around 4-5% of wages, split between employer and employee.

The unemployment insurance component rested on even more optimistic assumptions. Beveridge projected unemployment would rarely exceed 3% of the workforce and would be primarily frictional—workers between jobs, not structurally unemployed regions. He assumed the average unemployment spell would last weeks, perhaps a few months, never years. The system was designed to tide workers over brief gaps, not to support permanent worklessness.

His assumptions about family structure were equally precise.

He calculated benefits on the presumption of a male breadwinner with a dependent wife and children. Women would derive rights through their husbands, not as independent contributors. This dramatically simplified the system and reduced costs—you weren't supporting two separate benefit claims per household, but one.

Crucially, Beveridge assumed birth rates would remain high.

The post-war baby boom seemed to validate this. With three or four children per family, each generation would be substantially larger than the previous one, creating an expanding pyramid of workers to support a relatively small cohort of pensioners.

The original report as a PDF:

The Maths Now: How Every Assumption Collapsed

Today, roughly 23 million people in the United Kingdom receive some form of state assistance. The population is at least 68 million. That's not the 8% Beveridge envisioned claiming benefits at any given time—it's 34%.

There are now about 3.2 working-age people for every pensioner. By 2050, projections suggest this will fall to 2.8.

The pyramid has inverted.

Instead of many workers supporting few pensioners, you're approaching a one-to-one ratio where each worker must support themselves plus a pensioner.

But the dependency ratio only captures part of the crisis. The duration of dependency has exploded. People aren't retiring at 65 and dying at 75 anymore. A man reaching 65 today can expect to live another 19 years. A woman can expect 21 years. Many live far longer—into their late 80s or 90s.

Do the arithmetic: instead of 45 years of contributions funding 10 years of retirement, you now have 45 years of contributions (often less, given gaps in employment) funding 20-25 years of retirement. The ratio has inverted. For many people, they'll spend nearly as long drawing a pension as they spent paying into it.

In 1964, Britain's fertility rate peaked at 2.95 children per woman. Today it's around 1.5—well below replacement level. Each generation is approximately 30% smaller than the one before. Instead of an expanding pyramid, you have a shrinking one.

This creates a death spiral in the system's finances. Fewer workers means fewer contributions. More pensioners means more claims. Longer retirements mean each claim lasts decades rather than years. The mathematics become impossible.

Meanwhile, Beveridge's assumption of near-universal employment never recovered after the 1970s. Unemployment did drop from its 1980s peaks, but this masks a larger problem: millions of working-age people have simply left the labour force. Some claim disability benefits. Others take early retirement. Some exist on the margins in informal work.

Official unemployment might conveniently and coincidentally always be around 4%—unnaturally close to Beveridge's assumption—but the employment rate tells a different story. In 1971, about 92% of working-age men were employed. Today it's around 79%. Millions of men have stopped working, often ending up on benefits instead.

The Neverending Healthcare Catastrophe

The NHS—the jewel in the Beveridge crown—faces perhaps the starkest arithmetic crisis, and here Beveridge's miscalculation was almost comical in hindsight.

He genuinely believed healthcare costs would fall over time. His reasoning seemed sound: treat people early, cure infectious diseases, improve public health, and you'd have a healthier population requiring less medical intervention. He projected the NHS budget would peak in the early 1950s then gradually decline as the population became healthier.

He was spectacularly wrong.

The average person now consumes the majority of their lifetime healthcare spending in their final two years of life. With people living into their 80s and 90s, those final years cost vastly more than Beveridge's generation could have imagined.

The NHS budget in 1950 was about £400 million—roughly 3.5% of GDP. Today it's over £180 billion, approximately 8% of GDP. Adjust for inflation and population growth, and the per capita cost has still increased by a factor of four or five. The demands are infinite and growing.

Beveridge assumed medical science would eliminate disease. Instead it learned to manage chronic conditions for decades. Cancer patients who would have died in months now survive for years on drugs costing tens of thousands per treatment cycle. Premature babies who couldn't have survived in 1948 now live thanks to intensive neonatal care costing hundreds of thousands per child. Dementia patients exist in care homes for a decade or more, often requiring round-the-clock supervision.

Every medical advance increases costs rather than reducing them. You don't cure people and send them home healthy—you keep them alive longer in an increasingly expensive state of managed decline.

The Family Structure Collapse Of The 70s

Beveridge's calculations depended absolutely on the male breadwinner model remaining dominant. This wasn't just a social preference—it was a mathematical necessity.

By designing benefits around households rather than individuals, and by assuming wives would derive rights through husbands, he cut the system's costs roughly in half. One contribution record, one benefit claim per family. The pension a retired couple received was only marginally higher than what a single man would get, because the assumption was they were sharing housing costs and living expenses.

This model disintegrated.

The divorce rate, which was roughly 1 per 1,000 marriages in 1942, is now around 42%. Nearly half of marriages end in divorce. Suddenly you don't have two people living on one pension—you have two separate households, both requiring benefits.

Single parenthood exploded. In 1961, about 2% of families with children were headed by single parents. Today it's about 15%. Each single-parent household requires housing benefit, child benefit, and often in-work support or unemployment benefits.

These are costs Beveridge never budgeted for.

Women's employment changed everything. In 1951, about 35% of married women worked. Today it's over 70%. This should have strengthened the system—more workers, more contributions.

Instead it created new costs: childcare support, parental leave, tax credits to make work pay when both parents work and housing costs soar.

The system was never designed for dual-earner couples. Beveridge assumed one worker per household. When you have two workers, the household income rises, but so do costs: childcare, transportation, work clothes, convenience foods. The system's means-testing penalises couples in ways it never penalises single people, creating perverse incentives for families to separate.

The Contribution Fiction That Died Years Ago

Here's something most people don't understand: National Insurance stopped being insurance decades ago. It's just another tax, except more regressive because it doesn't apply to investment income or rental income—only wages.

Beveridge designed a genuine insurance system. You paid contributions during your working life. Those contributions entitled you to benefits when you needed them. The link was explicit: X years of contributions entitled you to Y years of pension. It was actuarially sound, just like private insurance.

This principle collapsed as means-tested benefits proliferated.

Today's welfare state is dominated by Universal Credit, Pension Credit, Housing Benefit, and other payments based on current income and savings, not contribution history.

This creates the perversity where someone who worked minimum wage jobs for 40 years and saved £20,000 might end up worse off in retirement than someone who never worked and has nothing. The saver won't qualify for Pension Credit or other top-ups. The non-saver gets everything.

Beveridge would have been horrified. His system was designed to reward work and thrift. It now punishes both.

The contributory principle also breaks down when huge swaths of the population aren't making contributions. In Beveridge's model, perhaps 3% were unemployed at any time.

Today, when you include the long-term sick, disabled, early retired, and those who've given up looking for work, perhaps 20% of working-age adults aren't contributing. The system depends on everyone paying in most of the time.

Instead, millions never pay in at all.

How Immigration Makes It Worse

The obvious solution—import more workers—creates its own crisis, and understanding why requires looking at the detailed arithmetic Beveridge relied on.

His model depended on lifetime net contributors.

A worker pays in from age 20 to 65, draws benefits from 65 to 75. Over that lifetime, they're net positive to the system by a large margin. The ratio of contribution years to benefit years is roughly 4:1 or 5:1.

Immigration disrupts this. Many immigrants arrive in their 30s or 40s. They might contribute for 20-25 years before retiring. But they'll draw a full pension for 20-25 years. The lifetime ratio of contributions to benefits is closer to 1:1. They're not net contributors—they're neutral at best.

Many immigrants work in low-paid sectors: care, hospitality, agriculture. They pay relatively little tax while qualifying for in-work benefits—tax credits, housing benefit, child benefit. An immigrant care worker earning £12 per hour might pay £3,000 per year in income tax and National Insurance, but receive £8,000 in housing benefit plus child benefit for two children. They're net recipients from day one.

Additionally, many immigrants bring families or have children after arriving. Those children require schooling, healthcare, and eventually benefits themselves. Parents may bring elderly relatives who've never contributed but immediately access NHS services. The fiscal cost compounds across generations.

Between 1997 and 2020, net immigration to the UK was about 4.6 million people. Since 2020, it's been roughly 700,000 per year. Academic research increasingly suggests non-EU immigration has been a net fiscal drain, not a contribution. EU immigration was modestly positive, but that's largely ended with Brexit.

The result is perverse:

- You import people to reduce the benefits bill, but they increase it.

- So you need more immigration to cover the shortfall.

- Which increases demand for housing, schools, and hospitals.

- Which increases costs.

- Which requires more immigration to fund.

The system has become a pyramid scheme—you need constant growth at the bottom to pay earlier entrants, but each new cohort creates fresh obligations.

More fundamentally, immigration doesn't solve the dependency ratio—it postpones it. Those young workers imported today will be pensioners in 40 years, requiring support themselves.

Unless you have infinite exponential population growth (you can't), the mathematics catch up eventually. You're borrowing from the future to pay for the present.

The Ponzi Scheme Can't Continue

Ponzi schemes work because early investors get paid from new investors' money rather than from actual returns. It functions smoothly as long as new money keeps flowing in. The moment it stops, the scheme collapses.

The Beveridge Model has become structurally identical. Current workers' contributions pay current pensioners' benefits. This is called a pay-as-you-go system, and it works if each generation is larger and richer than the last.

Beveridge designed it this way deliberately.

He could have created a funded system—where your contributions go into an investment fund that grows and pays your own pension later. Singapore does this with the Central Provident Fund. But funded systems require decades to build up capital, and post-war Britain needed immediate relief.

So Beveridge built a pay-as-you-go system.

The first generation of pensioners received benefits immediately, funded by the current generation of workers. Those workers were promised when they retired, the next generation would fund them. And so on forever.

This only works if the pyramid keeps expanding. When the pyramid inverts—fewer workers, more dependents—the scheme requires either drastic benefit cuts or unpayable tax increases.

Britain is now deep into the inverted pyramid phase. The state pension alone costs about £110 billion per year—roughly 5% of GDP. Add in pensioner benefits (winter fuel allowance, free bus passes, TV licences), NHS costs for the elderly, and social care, and you're approaching 12-15% of GDP spent on the elderly.

Meanwhile, the tax base shrinks. Working-age benefits (Universal Credit, housing benefit) cost another £50-60 billion. Healthcare for the working-age population costs perhaps £70-80 billion. Disability benefits, child benefit, and other transfers add tens of billions more.

You're asking a shrinking workforce to fund a growing dependent population, and the mathematics are brutal. The only ways to make this sustainable are:

- Increase contributions dramatically (National Insurance would need to double or triple)

- Cut benefits drastically (pensioners would need to accept a 30-40% reduction)

- Raise the pension age significantly (to 70 or 75, and keep raising it)

- Achieve miraculous productivity growth (hasn't materialised in 15 years)

Even if you did all of these simultaneously, demographics trump policy. Longevity keeps rising. Birth rates keep falling. Barring a baby boom (fertility has been below replacement for 50 years) or a productivity revolution (real wages haven't grown since 2008), the dependency ratio will keep worsening.

The Feedback Loops Nobody Planned For

Beveridge made a category error. He treated the welfare state like physical infrastructure—sewers, roads, railways. Build it once, maintain it, and it functions indefinitely. But physical infrastructure doesn't change human behaviour. Welfare systems absolutely do.

Generous benefits reduce work incentives. This isn't a moral judgment—it's arithmetic. If you can receive £18,000 per year in benefits or work full-time for £22,000, the marginal gain from working is £4,000. Once you factor in work costs (transportation, childcare, work clothes), the net gain might be £1,000 or less. Many people rationally choose not to work.

Means-testing creates poverty traps. As your income rises, you lose benefits. The effective marginal tax rate for moving from benefits into low-paid work can exceed 70% or 80% when you account for lost housing benefit, council tax support, and Universal Credit withdrawal. You're working more hours for almost no additional income.

Housing benefit inflates rents. Landlords know tenants have access to benefits, so they price accordingly. The government ends up subsidising private landlords to house people who can't afford market rates. But this makes market rates more expensive, increasing the benefits bill, requiring more spending. It's a feedback loop with no exit.

In-work benefits subsidise low wages. Tax credits and Universal Credit top up earnings for millions of workers. This lets employers pay less—they know the state will make up the difference. So wages stagnate, requiring more in-work support, allowing wages to stagnate further. The government ends up subsidising corporate payrolls.

Single-parent benefits make lone parenthood economically viable in ways it historically wasn't. Before the welfare state, single motherhood generally meant destitution unless family could help. Now the state provides housing, income support, and childcare assistance. This isn't to judge single parents—but the economic incentives have changed. Behaviour responds to incentives.

Disability benefits create an avenue for labour force exit. Many people in regions with collapsed industries ended up on disability benefits in the 1980s and 1990s, not because they became disabled, but because it was an administratively easier way to manage structural unemployment. Disability rolls exploded and never contracted.

None of this means individuals are lazy or feckless—most people respond rationally to the incentives they face. But collectively, these individual responses create feedback loops that break the system's mathematics.

Beveridge assumed cultural stigma would informally ration claims. In his era, going on the dole was shameful. Families would exhaust private savings, borrow from relatives, take any work rather than claim parish relief. This constraint kept costs down even when people were technically eligible for help.

That stigma has mostly vanished. When claiming benefits is normalised, more people claim them.

The system depends on most people never claiming even when eligible, but that assumption no longer holds.

The Question Nobody Wants To Answer

Here it is, stated plainly: who gets cut?

The system promises pensions to everyone over 66. It promises healthcare to 68 million people. It promises support for the unemployed, the disabled, the elderly, the poor. But the arithmetic doesn't work. Something has to give.

Raise taxes? Britain's tax burden is already at a 70-year high, around 36% of GDP. Push it to 40% or 45%—levels needed to actually fund current promises—and you discourage work, entrepreneurship, and growth. You also trigger capital flight. The wealthy leave, taking their tax contributions with them. The tax base shrinks even as rates rise.

Cut benefits? You immediately impoverish millions and face electoral annihilation. Pensioners vote reliably. They're also the demographic cohort most protected politically—they lived through the generous decades and feel entitled to what was promised. Even if you had the votes, the transition would be brutal.

Pensioners can't suddenly find work. Disabled people can't suddenly get better. Single mothers can't suddenly stop being single mothers.

Economic growth? Perhaps, but Britain hasn't managed sustained productivity growth since 2008. Real wages for most workers haven't risen in 15 years. GDP growth has averaged 1-2% annually, barely keeping pace with population growth. Absent a technological revolution or major reforms to boost productivity, growth won't save you.

You'd need 4-5% annual growth sustained over decades to grow your way out of this arithmetic crisis.

Print money? You can devalue your way out of nominal obligations, but you can't print doctors, nurses, or houses. Inflation makes everyone poorer in real terms. It's a hidden benefit cut, but the mathematics still don't work.

The Predictable Folly Of Liberalism

The cruel irony is that Beveridge was a Liberal, not a socialist. He designed his system explicitly to preserve capitalism and individual liberty. The welfare state was meant to establish a minimum—a floor below which nobody would fall—but not to equalise outcomes or abolish class.

He wanted work incentives preserved. He wanted people to save privately above the state minimum. He opposed earnings-related benefits precisely because they would reduce the incentive to earn more. He imagined voluntary societies and mutual aid organisations sitting alongside—not being replaced by—the state.

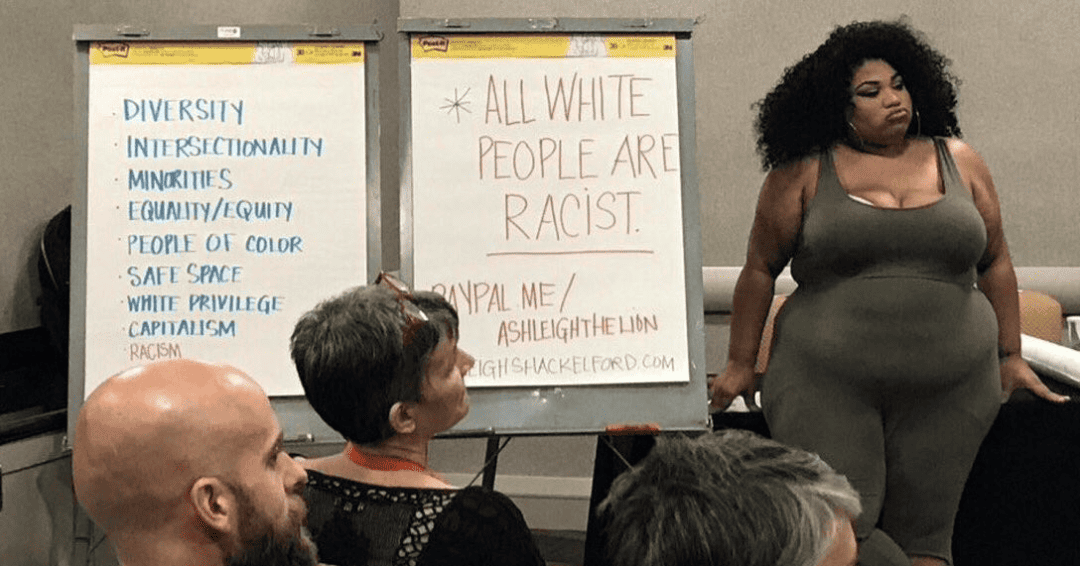

His report explicitly stated:

The State in organising security should not stifle incentive, opportunity, responsibility; in establishing a national minimum, it should leave room and encouragement for voluntary action by each individual to provide more than that minimum for himself and his family.

This vision died.

His system failed not because socialists hijacked it (though they tried), but because its liberal premises proved unsustainable.

- You cannot have a minimal, temporary safety net when a third of the population needs it permanently.

- You cannot preserve work incentives when the gap between benefits and low wages is trivial.

- You cannot encourage private saving when means-testing punishes it.

Beveridge built a system for a world of stable families, full employment, and social conformity.

He got family breakdown, mass unemployment, and individualism. The mathematics collapsed not because of ideological subversion, but because every assumption proved false.

Where This Ends

Not with a solution—there isn't one that's both politically feasible and economically sound. Every option involves pain.

You could attempt a Singaporean model: forced savings accounts, minimal state provision, expectation of family support. It would work mathematically but would require immense political will and transitional hardship. It would also abandon the universalism that made the original system legitimate.

You could pursue a Nordic model: higher taxes, more generous benefits, active labour market policy. But Scandinavia's model is itself under strain, faces the same demographic pressures, and depends on a social cohesion Britain doesn't possess and can't recreate.

You could simply let the system decay: freeze benefits in real terms, raise the pension age indefinitely, ration healthcare, and hope the middle class can fend for itself.

This is Britain's current path—managed decline rather than reform.

Or you could be honest: admit the Beveridge Model is dead, stop pretending it can be saved, and begin a painful conversation about what replaces it. This requires acknowledging that the promises made to today's young workers like Nick, 30 ans—that they'll receive pensions, healthcare, and support in their old age—are promises the state cannot keep.

Twenty-three million people on benefits. A dependency ratio of 3.2 workers per pensioner, falling to 2.8. Fertility at 1.5 children per woman. Retirements lasting 20-25 years instead of 10. Mass immigration that doesn't fix the fiscal gap but creates new obligations. The mathematics are brutal and unavoidable.

Beveridge designed a system for a country that no longer exists, based on assumptions that proved comprehensively false.

- The birth rate didn't stay high—it collapsed.

- Employment didn't stay universal—millions left the workforce.

- Families didn't stay together—they fragmented.

- Retirements didn't stay brief—they doubled in length.

- Medical costs didn't fall—they exploded.

Every single variable in his equation moved in the wrong direction simultaneously. The system cannot be reformed because the problem isn't policy—it's arithmetic. You cannot tweak eligibility rules or adjust contribution rates when the fundamental dependency ratio makes the system mathematically impossible.

Britain needs to stop mourning what's been lost and start calculating what's actually possible. The alternative is fiscal collapse, social breakdown, or both.

The fatal flaw wasn't in Beveridge's intentions—it was in building a permanent system on temporary assumptions. He thought he was constructing a cathedral. He actually built a house of cards. And in 2025, with 23 million people depending on it, the cards are falling.