The Next British Empire Of The Heavens & The Seas

Three discoveries in physics and a few months of NHS spending stand between Britain's place as a second-rate power and a hundred years of global dominance. Whomever solves these problems will control the chokepoints of human development and make both American and Chinese size irrelevant.

America and China fight for the one-day glory of putting a man on a dead planet. Meanwhile, the seas call. The stars beckon. Frontiers beyond imagination await.

These words are not poetry. They are prophecy — or they could be, if Britain remembers what she once knew: empires are not built by occupying land, but by commanding the passages between lands. The nation which controls the chokepoints controls the world.

A small island off the coast of Europe once held dominion over a quarter of the Earth's surface. Not through vast armies marching across continents, but through a handful of rocks and harbours scattered across the globe — Gibraltar, Suez, Singapore, the Cape — each one a lock, and Britain holding every key. The principle was elegant in its simplicity: geography concentrates value at certain points, and he who holds those points holds everything.

The old empire is gone. But the principle which made it possible has not vanished. It has migrated — upward, into the heavens, and downward, into the depths.

The next empire will not be measured in square miles of territory. It will be measured in command of two domains: the oceans, which still carry ninety per cent of global trade and beneath whose surface lie resources and possibilities we have barely begun to imagine, and space — that vast expanse above our atmosphere where satellites orbit, where future industries will be built, and where the military and commercial high ground of the coming centuries awaits its claimant.

Whoever masters these two realms will rule for a thousand years.

The New Frontier Has No Borders

The ocean depths and the reaches of space share a characteristic which distinguishes them from all previous frontiers: they cannot be divided into the neat parcels of territory which define nation-states on land. There are no fences in orbit. There are no border posts on the seabed. Sovereignty in these domains belongs not to whoever plants a flag, but to whoever can project power, maintain presence, and deny access to rivals.

These are the realms where the future will be decided. And they are realms peculiarly suited to a small island nation with a long memory and a genius for leverage.

Consider what Britain achieved with a few dozen strategically placed outposts. Then consider what might be achieved by a nation which commanded not rocks and harbours, but the fundamental technologies upon which all future progress depends.

For there exists another kind of chokepoint, more powerful even than geography: the scientific breakthrough. Steam power was such a chokepoint — whoever mastered it first, making machines do human labour, commanded the industrial revolution. The telegraph was another: instant communication across oceans gave those who possessed it an insurmountable advantage in commerce, diplomacy, and war. Radar won the Battle of Britain before the first Supermarine Spitfire scrambled.

These were not incremental improvements. They were phase transitions — moments when the entire structure of power shifted because someone had unlocked a capability previously thought impossible. And they were, in almost every case, British.

The comfortable assumption of our age is progress happens gradually, predictably, through the steady accumulation of small advances. This is a comforting lie. History moves in sudden leaps. The nation which triggers the next transformation will inherit the next era of human civilisation.

Three Discoveries To Empire

There are, today, three scientific challenges which — if solved — would not merely advantage their possessor but would remake the world entire. Three keys waiting to be forged. Three flames waiting to be kindled.

The minds capable of solving them exist. The theoretical foundations are laid. What remains is the work — and the will to pursue it.

Unlocking The Ocean: Seawater to Liquid H2 + Freshwater

Water is hydrogen and oxygen bound together — the two most useful elements in the universe locked in an ancient embrace. Split the bond, and you hold in your hands the fuel of the future and the breath of life itself. Fire and air, energy and sustenance, fused into a single, ubiquitous compound which falls from the sky and fills the seas.

Not Prometheus stealing fire from the gods, but Epimetheus.

The splitting of water has been understood for two centuries. The obstacle has never been knowledge, but thermodynamics and energy: it costs more to break the bond than the hydrogen, when burned, can return. This single constraint has kept humanity shackled to petroleum, to the geopolitics of oil, to the grotesque spectacle of free nations genuflecting before desert autocracies for permission to power their economies. Entire wars, alliances, and fortunes have flowed from this imbalance, not because oil is precious, but because alternatives were constrained by physics.

Who electrolysed water? The British, in 1800.

The difficulty is not trivial. Water is an unusually stable molecule, and its stability is precisely why life depends upon it. Breaking the hydrogen–oxygen bond requires overcoming a steep energy barrier, and every known method — electrolysis, thermochemical cycles, photoelectrochemical splitting — loses energy to heat, resistance, and entropy. Catalysts help, but only by shaving margins; they cannot repeal the underlying thermodynamic accounting. For two centuries, this inefficiency has been decisive: hydrogen has remained an energy carrier, not a primary source, useful only where surplus power already exists.

And yet, this is precisely what plants do every day. Photosynthesis splits water molecules millions of times per second using nothing more exotic than sunlight, protein complexes, and time. Nature proves the process is possible — not cheaply, not quickly, but reliably and at planetary scale — suggesting the barrier is not physical impossibility, but our failure to replicate, accelerate, or surpass a solution evolution arrived at first.

But imagine the constraint broken.

Imagine a breakthrough — call it synthetic hydrolysis — which allows seawater to be split at near-zero net energy cost. Perhaps a new catalyst. Perhaps a novel molecular process. Perhaps an engineering solution not yet conceived. The mechanism matters less than the consequence.

Suddenly, the oceans themselves become fuel. Liquid hydrogen flows from processing plants on every coastline. The petroleum economy — the wells, the refineries, the tankers, the pipelines, the petrostates — becomes a relic within a generation. Every nation with a shore becomes energy independent by default. The strategic importance of the Middle East evaporates like morning fog, not through conflict or diplomacy, but through obsolescence.

But follow the thread further. Hydrogen combustion produces water as exhaust. A hydrogen-powered vehicle is also a water-production system. Deserts with ocean access become irrigable. The Sahara greens. The Arabian wastes bloom. Drought — mankind's oldest enemy — becomes a solved problem.

And further still. Seventy per cent of Earth's surface is ocean. If splitting seawater is cheap, then the world's seas become the world's freshwater reservoirs. The Western Sahara becomes a rainforest. Humanity's relationship with water itself — the compound upon which all life depends — is rewritten in a single generation.

This is not fantasy. The chemistry is real. The physics permits it. What remains is engineering — and engineering is what Britain does better than almost any nation which has ever existed.

Mastery Over Every Domain: Multi-Modal Hyper-Propulsion

There is a barrier at seven hundred and sixty miles per hour where the air itself resists passage. For decades it was thought unbreakable. Then it broke. There are further barriers beyond — thermal, structural, physical — and each has been pushed back by ingenuity and will.

Yet we remain, fundamentally, constrained. The fastest airliners cruise at six hundred miles per hour, scarcely faster than they did in 1970. The fastest submarines creep through the depths at forty miles per hour. The boundaries between air and sea and space remain as impermeable as castle walls, each domain requiring its own vehicles, its own infrastructure, its own limits.

But what if those walls came down? What if we discovered a new means of propulsion?

What would follow would not be a faster aircraft or a better submarine, but the collapse of the domains themselves. Air, sea, and space would cease to be separate theatres of movement, each governed by its own tyranny of drag, pressure, and heat. Instead, propulsion would become adaptive: field-based in atmosphere, inertial in vacuum, cavitational beneath the ocean, the same vehicle reconfiguring its interaction with the medium rather than surrendering to it. Speed would no longer be paid for in fuel alone, but achieved through mastery of energy, geometry, and flow. The vehicle would not fight its environment; it would step aside from it.

Such a breakthrough would redraw the map of power. Distance would lose its meaning. Borders enforced by oceans would thin, then vanish. Logistics chains would compress from weeks to minutes; response times from hours to seconds. Surveillance, deterrence, trade, and exploration would all be reshaped by the same brutal fact: whoever moves first, fastest, and without constraint governs the tempo of the world. This would not merely be an advance in transport, but a reordering of strategy itself — a transition as profound as the shift from sail to steam, or from propeller to jet — and one whose consequences would reach far beyond engineering, into politics, warfare, and the structure of civilisation.

Imagine a vehicle capable of sustained travel at ten thousand miles per hour — not in one domain, but in all of them. In the vacuum of space, certainly, where no air resists. But also in atmosphere, through propulsion systems not yet invented. And beneath the waves, where supercavitation wraps the craft in a skin of gas and allows it to slip through the ocean at a thousand miles per hour, silent, invisible, unstoppable.

The implications shatter the mind.

A vessel departs Cape Town, dives beneath the Atlantic swells, and surfaces in London before a conventional flight has crossed the Mediterranean. Aircraft carriers become museum pieces when any point on their deck can be reached from any point on Earth in minutes. The hurricane which grounds every aircraft and imperils every ship becomes irrelevant to a craft which simply dives beneath it and continues on its way.

The entire geography of human settlement transforms when distance ceases to impose its ancient costs. Every city becomes a neighbour to every other. Every shore becomes a gateway to everywhere.

And imagine further: a vehicle which moves between domains as easily as a bird moves between branch and sky. Descending through atmosphere, diving beneath waves, rising to orbit — a single craft, a single journey, the walls between elements dissolved into seamless passage. The boundaries which have defined human movement since the first boat touched water cease to exist.

Who first suggested it? The British, in 1920.

Chemical rockets have been eclipsed in ambition by nuclear thermal and nuclear electric propulsion, nuclear salt-water rockets, fusion pulse systems, antimatter drive theory, and even photon rockets approaching the theoretical limit of exhaust velocity. Electric and plasma propulsion — ion drives, Hall-effect thrusters, magnetoplasmadynamic, helicon, electrospray and VASIMR engines — already exchange thrust for efficiency at scales once unimaginable. Beamed propulsion removes engines from vehicles entirely, using laser, microwave and photon sails, pellet streams, and laser-boosted lightcraft to trade onboard mass for external infrastructure. Beyond this lie field-interaction concepts such as Mach Effect Thrusters, inertial mass fluctuation devices, quantum vacuum plasma propulsion and Casimir-based effects, which seek thrust without conventional exhaust, while spacetime-based approaches — Alcubierre and Natário warp metrics, Krasnikov tubes and metric engineering — propose propulsion by reshaping geometry rather than applying force. In dense media, supercavitation, plasma-assisted cavitation, magnetohydrodynamic and electrohydrodynamic propulsion, combined with trans-medium, domain-adaptive architectures, point toward vehicles that no longer submit to air, water or vacuum, but renegotiate the terms of motion themselves.

This is the mastery of every domain. This is what awaits the nation bold enough to pursue it.

The Infinite Mind: Quantum Chip Thermodynamic/Photonic Personal Computing

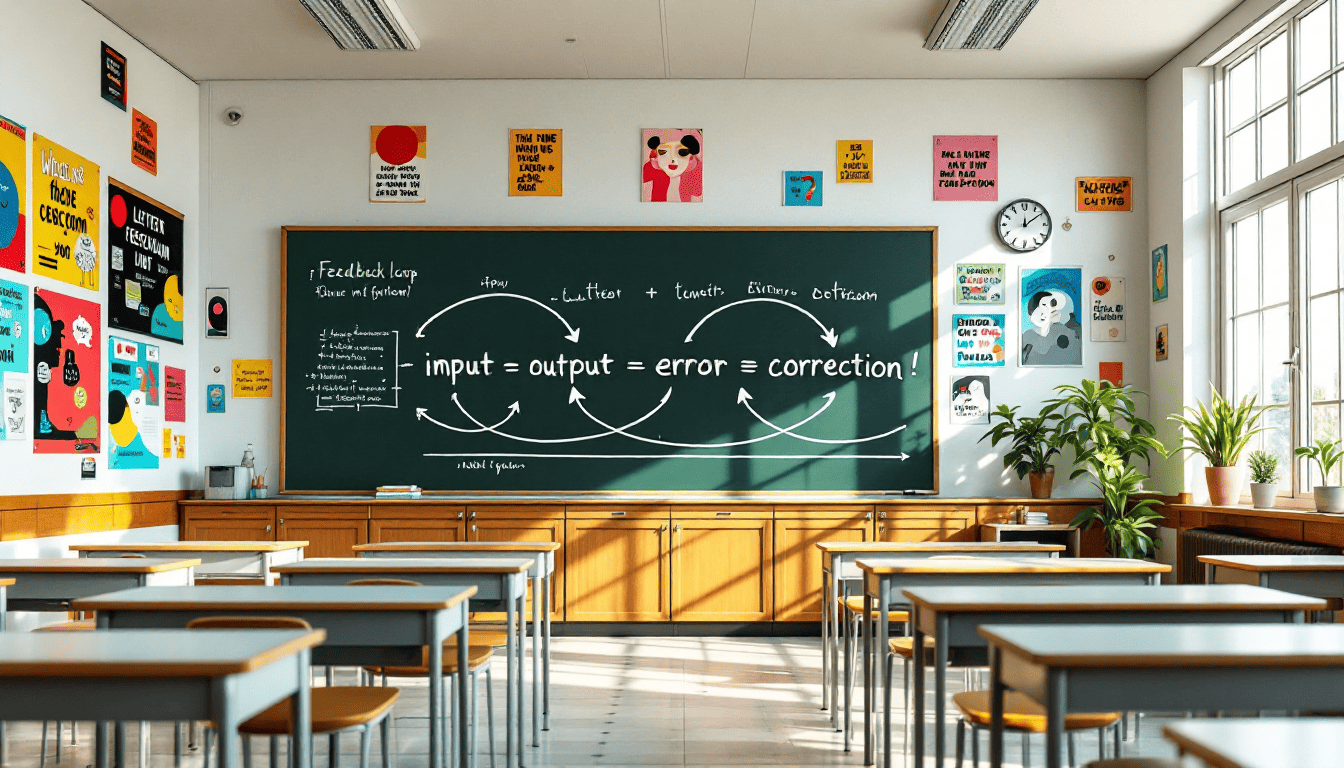

Every computer ever built faces the same inexorable enemy: heat. Computation requires energy, and energy degrades into waste heat, and waste heat must be dissipated or the machine destroys itself. This is not a design flaw. It is thermodynamics. It is law.

For half a century, engineers postponed this reckoning through ingenuity rather than repeal. Transistors shrank, voltages fell, clocks rose; Dennard scaling and Moore’s Law worked their quiet miracles. But those tricks are spent. At nanometre scales, electrons tunnel where they should not, leakage currents rise, interconnects dominate delay, and cooling becomes geometry rather than engineering. Even in theory, computation carries a minimum energy cost — the Landauer limit — a reminder information itself has thermodynamic weight. Each erased bit must pay its toll in heat, and the bill comes due whether the computer sits in a hyperscale facility or a pocket.

What we are confronting is not a temporary bottleneck, but the point at which information processing collides directly with the physical structure of reality.

This is why artificial intelligence, for all its promise, remains chained to vast data centres gulping gigawatts beside cold rivers. This is why the phone in your pocket contains a fraction of the power available in a desktop machine. There is no way — yet — to dissipate the heat a more powerful chip would generate in so small a space.

The heat barrier is the final constraint on computing. Break it, and everything breaks open. And every investment America or China have made in data centres becomes meaningless.

Quantum chips do not merely accelerate computation; they evade its classical assumptions. Where conventional processors manipulate bits that must be charged, discharged, and erased — each step exacting its thermodynamic toll — quantum devices operate on superposition, interference, and entanglement. Information is not pushed through gates so much as allowed to evolve. For certain classes of problems, the computation happens in the physics itself, with answers emerging from measurement rather than iteration. The challenge is not raw power but fragility: quantum states decohere, collapse, and demand isolation so extreme today’s machines still live inside refrigerators. Yet the trajectory is clear.

Reversible and thermodynamic computing seeks to minimise bit erasure itself, designing logic which preserves information and therefore sheds far less heat. Photonic computing goes further, replacing electrons with light — photons which generate negligible resistance, travel at unmatched speeds, and can pass through one another without interference. Computation becomes a matter of phase, wavelength, and resonance rather than current and voltage. Neural networks already map naturally onto optical systems, hinting at processors that think at the speed of light while barely warming the air around them.

What could you do with more processing power in your palm than exists in every data centre on Earth combined?

The artificial intelligence such devices could run would not be the clever parlour tricks we know today. It would be genuine cognitive augmentation — systems capable of scientific reasoning, of invention, of creativity indistinguishable from the highest human genius. Every person becomes a polymath. Every workshop becomes a research laboratory. Every home contains more intellectual capability than the whole of humanity possessed before the computer age began.

The vast server farms of California and Virginia become monuments — museums commemorating an era when intelligence required industrial infrastructure to house it. Power shifts from those who control the data centres to those who design the chips. And those who design the chips could be anywhere.

Including here.

Where One Spark Lights Another

These three breakthroughs are not isolated possibilities. They form a constellation — each illuminating the others, each amplifying the others, each making the others not merely possible but inevitable.

Cheap hydrogen provides the energy for hypersonic propulsion without the chains of petroleum dependency. Advanced computing provides the design capability to solve the engineering challenges of both. Mastery of the oceans and the heavens provides the proving grounds where these technologies mature into dominance. Together, they do not merely add to one another. They multiply. They compound. They create a civilisational explosion which would make the first industrial revolution look like a spark before a bonfire.

Consider what Britain would become with even one of these flames kindled.

With synthetic hydrolysis alone: energy independence absolute and permanent. The North Sea, the Channel, the Atlantic — not barriers but batteries, inexhaustible reserves of fuel lapping at our shores. The rusting refineries of Grangemouth and Ellesmere Port transformed into gleaming hydrolysis plants, exporting clean hydrogen to a world desperate for it. The strategic leverage of the Persian Gulf transferred, at a stroke, to any nation with a coastline and the wit to exploit it. Britain, an island surrounded by fuel, would never again bow to foreign powers for permission to keep the lights on.

With multi-modal propulsion alone: the tyranny of distance abolished. Glasgow to Sydney in three hours. Cargo from Shanghai arriving in Felixstowe before the paperwork clears. A Royal Navy capable of projecting power to any ocean, any depth, any theatre, faster than any adversary can respond. The Atlantic becomes a lake. The Pacific becomes a pond. The old maps, with their daunting expanses of blue, shrink to the dimensions of a country garden.

With thermodynamic computing alone: the democratisation of genius. Every child with a device containing more cognitive power than every university combined. Every entrepreneur with access to design capabilities currently reserved for billion-dollar corporations. Every scientist with a research partner of unlimited patience and superhuman capability. The bottleneck of human intelligence — the cruel fact that brilliance is rare and cannot be manufactured — shattered forever.

Now consider all three together as a system.

Dare To Imagine Daily Life

Imagine waking in a Britain which has mastered these technologies.

You rise in a home heated and powered by hydrogen drawn from the sea five miles distant. The fuel cost is negligible — less than you once paid for a single tank of petrol. The air outside is cleaner than it has been since before the first factory chimney rose over Manchester. The power grid is a relic; your home generates what it needs and sells the surplus to neighbours whose panels caught less sun.

Your children leave for school carrying devices which would have been classified military technology twenty years ago. Their teacher is assisted — not replaced, but genuinely assisted — by intelligence systems which can explain calculus in fourteen different ways until comprehension dawns, which can detect confusion before it becomes frustration, which can nurture each mind according to its particular shape and speed. The gap between the child of privilege and the child of poverty narrows, then closes, then vanishes — because genius-level tutoring is no longer a commodity for the wealthy but a birthright for all.

You travel to work in a vehicle which draws its fuel from the tap and emits nothing but water vapour. Or perhaps you do not travel at all — perhaps you work, as millions now do, in collaborative spaces which render physical presence optional for most purposes. But when you must travel, you travel fast. The train to Edinburgh takes forty minutes. The flight to New York takes ninety. The hop to Singapore — should you need it — takes less time than your grandparents spent commuting from Surrey to the City.

The factories hum again. Not the dark satanic mills of old, but gleaming automated facilities where British-designed machines produce British-invented technologies for export to a hungry world. The money flows in — not the false prosperity of financial engineering and property speculation, but real wealth generated by making things other nations cannot make and solving problems other nations cannot solve.

And beyond the factories, in laboratories scattered across the land, the next generation of breakthroughs takes shape. Because a nation which has learned to pursue the impossible does not stop at the first impossibility conquered. The culture of ambition, once rekindled, burns ever brighter. Each success breeds confidence. Each confidence breeds attempt. Each attempt — even those which fail — breeds knowledge and determination for the next.

Imagine Explaining Computers In 1689

The great powers of the twenty-first century jostle for advantage — America with her capital and scale, China with her manufacturing might and patient planning, the rising nations of India and Brazil and Indonesia pressing their claims. Amidst them stands Britain: small in territory, modest in population, yet holding the keys which all of them require.

A locked door is useless wood without keys.

They need hydrogen technology. We license it — on our terms. They need propulsion systems for their navies and airlines. We provide them — at our price. They need the computing architectures which power the next generation of artificial intelligence. We design them — in our facilities, employing our people, generating our wealth.

This is not fantasy. This is precisely what Britain did for a century and a half with its patent system licensing the technologies of the first industrial revolution. It's exactly what happened in the nineteenth century: a simple repeat of a formula which worked.

We did not conquer the world by force. We made ourselves indispensable to it. We produced what others could not produce. We knew what others did not know. We held the chokepoints — not of geography, but of capability — and the world paid tribute for access.

The empire of the heavens would operate by the same logic. Not occupation but leverage. Not domination but indispensability. Not the hard power of armies but the harder power of knowledge which cannot be stolen because it requires an entire culture to generate and sustain.

Let others build larger militaries. Let them raise taller towers and dig deeper mines. Britain's power was never in size. It was in wit. It was in the capacity to solve problems others could not solve, to see possibilities others could not see, to build what others said could not be built.

This capacity has not disappeared. It has been sleeping. It waits only for the alarm.

Why Not Us? Why Not Now?

There is a voice — you have heard it, we have all heard it — which whispers that such ambitions are not for us. That Britain's day has passed. That we are a medium-sized nation now, a post-imperial relic, fit only to manage decline with dignity and pray our betters treat us kindly.

This voice is a liar.

It lies about our past: as if the nation which transformed the world did so by accident, by luck, by forces beyond its control. It lies about our present: as if the universities of Oxford and Cambridge and Imperial, the research facilities and engineering firms, the traditions of innovation stretching back centuries have simply evaporated. It lies about our future: as if the laws of physics and the nature of human creativity have somehow been amended to exclude these islands from greatness.

The voice whispers because it fears what would happen if we stopped listening.

Britain invented forty-five per cent of the modern world. This is not poetry. This is accounting. The steam engine. The railway. The telegraph. The telephone. The television. The computer. Radar. Antibiotics. The jet engine. The structure of DNA. The World Wide Web. Each of these emerged from British minds working in British institutions, and each transformed the entire subsequent history of the human race.

- The British invented water electrolysis.

- The British suggested molti-modal vehicles, invented the turbojet, and perfected vertical takeoff.

- The British invented computing.

Were these achievements flukes? Were the men and women who accomplished them mutants, aliens, visitors from a more capable species who happened to reside on these islands for a few generations before departing?

Or were they the products of a culture — a particular, specific, identifiable culture — which valued ingenuity, rewarded practical achievement, tolerated eccentricity, and understood instinctively the relationship between theoretical knowledge and worldly application?

That culture has not been bred out of us. It has been bureaucratised. It has been credentialised. It has been smothered under regulations and reviews and risk assessments until the fire burns low. But coals remain. And coals can be fanned into flame.

The Obstacle Is Not Capability

Let us be absolutely clear about what stands between Britain and her empire of the heavens.

It is not intelligence. Our universities remain among the finest on Earth. Our scientific output, adjusted for population, exceeds that of virtually every competitor.

It is not resources. The seas which would provide our hydrogen surround us, and Britannia is ruler of the waves. The infrastructure which would support our industries exists or can be built. The capital which would fund our research could be summoned if the will existed to summon it.

It is not funding. We spend more a month on the NHS than empires spend on their own R&D.

It is not competition. Yes, America is powerful. Yes, China is rising. But technological breakthroughs do not belong automatically to the largest or wealthiest nations. They belong to whoever achieves them first and exploits them most rurthlessly — and first-mover advantage, in technologies of this magnitude, is worth more than all the armies and treasuries in the world.

No, this is not for the state to do. We are not waiting for bureaucrats to do it.

The obstacle is will. The obstacle is imagination. The obstacle is the peculiar modern British disease of believing ourselves incapable of greatness because we have spent so long settling for mediocrity.

The government fiddles with timetables and targets while the future slips through nerveless fingers. The civil service produces reports recommending further reports. The political class debates trivial redistributions of a pie they lack the ambition to enlarge. And all the while, the scientists and engineers and inventors who could transform everything wait for a nation worthy of their talents — or leave for nations which are.

This is not inevitable. It is chosen. And what is chosen can be unchosen.

Will We Seize Destiny?

History does not wait. The breakthroughs will be achieved. The only question is where.

Will synthetic hydrolysis emerge from a British laboratory, or will we purchase it from the Chinese and beg the Americans for permission to use it? Will multi-modal propulsion be pioneered by British engineers, or will we watch from the sidelines as other nations master every domain while we struggle to keep our railways running? Will the next generation of computing be British-designed, or will we remain consumers of others' genius, dependent and diminished?

These are not rhetorical questions. They are choices. They are being made, right now, in every decision to fund or not fund, to prioritise or neglect, to reach for greatness or settle for adequacy.

The seas call. They have always called to us — the island nation, the maritime power, the people whose history is written in salt water and sail canvas. The stars beckon, as they have beckoned since the first human looked upward and wondered. Frontiers beyond imagination await, as they awaited Drake and Cook and Franklin, as they awaited Stephenson and Brunel and Whittle.

The only question is whether we will answer.

Not whether we can — that question is settled. The capacity exists. The minds exist. The traditions exist. Everything required for greatness is present, here, now, waiting to be deployed.

The question is whether we will.

Time For The British To Decide

There comes a moment in the life of every nation when the path divides. One road leads downward — comfortable, familiar, requiring nothing but the management of existing decline. The other road leads upward — steep, demanding, uncertain, but rising toward heights from which the whole world can be seen.

Britain stands at such a division now.

The downward path is easy. We know its contours. We have been walking it for decades. More of the same: more consultations, more compromises, more careful calibrations of ambition to match diminished expectations. A dignified fade into irrelevance, punctuated by nostalgic ceremonies commemorating past glories we no longer believe ourselves capable of matching.

The upward path is hard. It requires investment on a scale not seen in generations. It requires political courage of a kind currently absent from public life. It requires a national commitment to excellence which cuts against every lazy instinct toward mediocrity. It requires, above all, the audacity to believe that what Britain has done before, Britain can do again.

But consider what lies at the summit.

Dominion over the seas and the heavens. Mastery of the technologies which will shape the next thousand years of human history. A second empire — not of territory, not of subject peoples, but of knowledge and capability and the power which flows from controlling the chokepoints to all.

The empire of the seas and heavens awaits its founder.

The choice is ours.