The Private Equity Childcare Scandal: Deaths, Abuse, and 22% Margins

Private equity firms extract 22% profit margins from vulnerable children whilst councils face bankruptcy paying £320,000 per placement. Behind closed doors: deaths, restraint abuse, and a broken market nobody will fix. It's time the state was held to account for allowing the trade in orphans.

One teenager had spent his last two days tying nooses from ropes in the garden. He showed them to the other children at Ivy Cottage and told them explicitly he was gearing up to hang himself. Staff were supposed to keep "an extra eye on the resident", according to employees, but there was "no real concern for Aaron."

When Aaron Leafe put on his best suit one Saturday evening, announced he wanted "peace and quiet" to write rap lyrics, and shut himself in an empty room, nobody checked properly. When staff finally knocked, there was no reply. The 15-year-old had hanged himself in a children's home run by Keys Group—a private equity-backed company managing dozens of residential facilities across England.

Aaron's 2010 suicide should have been a wakeup call. Keys claimed to "do our utmost" to keep children safe. But eight years later, a BuzzFeed News investigation exposed how Keys had continued cutting costs and chasing revenues whilst children went missing at rates far exceeding the rest of the sector. The company is now owned by private equity firm G Square Capital, which insisted previous incidents "relate to the previous administration."

Aaron's death represents just one tragedy in what has become Britain's privatised childcare scandal—an industry where profit margins dwarf outcomes, where vulnerable children have become assets in private equity portfolios, and where no major political party seems willing to confront the financial interests profiting from misery.

The Market Nobody Will Regulate

Walk into any council children's services department and you'll encounter a grim arithmetic. The average children's home placement now costs £318,400 per year. For children with complex needs requiring round-the-clock supervision, councils have been charged up to £63,000 per week—£3.3 million annually for a single child.

These astronomical sums have doubled in just five years, rising from £1.6 billion in 2020 to £3.1 billion in 2024. Yet the National Audit Office concluded in September 2025 that this expenditure delivers neither value for money nor appropriate care. Nearly half of children in residential care are placed more than 20 miles from home. Two-thirds are placed outside their local authority entirely. Many live in facilities with blood and faeces smeared on walls, broken toilets, and rooms reeking of urine.

The market structure explains this paradox. Around 84% of children's homes are now privately owned, with seven of the ten largest providers either owned or part-funded by private equity firms. Between 2016 and 2020, the Competition and Markets Authority found these 15 largest providers enjoyed average profit rates of 22.6%—amongst the highest margins in British social services. Fees rose faster than inflation whilst quality stagnated or declined.

CareTech (owned by Amalfi Midco Limited) and Keys Group (owned by G Square Healthcare Private Equity) dominate the landscape, controlling 9% of all children's homes between them. CareTech oversees 220 homes through 12 organisations. Keys owns 156 homes spread across 25 different entities. This fragmentation isn't accidental. Complex ownership structures obscure financial flows, making it nearly impossible for regulators to identify where money goes or what constitutes "excessive profit."

The Department for Education lacks access to provider financial data. It cannot assess fair costs, cannot determine reasonable pricing, cannot effectively implement a profit cap even as ministers promise to tackle "profiteering." The planned market oversight regime won't arrive until 2028-29—years away, whilst councils go bankrupt and children suffer today.

The Human Toll

Ofsted inspection reports reveal a litany of failures. At homes owned by the Hesley Group—charging local authorities £250,000 per child annually—leaked documents exposed systemic abuse over three years. Children were punched, kicked in the stomach, swung around by their ankles, locked outside naked in freezing temperatures. One child had chilli flakes fed to them and was denied water. Another received a black eye. Multiple children were locked overnight in bathrooms, deprived of medication for days, left in soiled clothes, forced to sit in cold baths.

More than 100 concerns were logged at Hesley's Doncaster homes between early 2018 and spring 2021. Ofsted was alerted 40 times about incidents. Yet these facilities retained a "good" Ofsted rating until October 2022, when an expert panel finally concluded there had been "systemic and sustained abuse." The homes closed. Staff were dismissed. Hesley apologised. But the children had already been harmed.

Both Hesley and Kisimul—the care provider one child had been moved from before arriving at the abusive Hesley home—share the same owner: private equity firm Antin Infrastructure Partners. Despite the documented abuse, Hesley's accounts recorded £12 million in profits for 2020, representing a 16% margin—close to the 17% the government watchdog considers "excessive."

Between April 2024 and March 2025, Ofsted received 34,481 serious incident notifications from children's homes. "Police call-outs to the home" accounted for a quarter of all notifications. These weren't exclusively about children committing crimes—police were called because children went missing, suffered sexual or criminal exploitation, disclosed historical safeguarding concerns.

Ofsted's Chief Inspector acknowledged in July 2025 seeing problematic patterns regarding restraint and restrictive practices during inspections. The regulator noted concerns about inappropriate physical restraint and "single separation"—the euphemism for isolating and locking children in rooms—when the circumstances didn't justify such measures.

Children go missing with alarming frequency. In 2024, there were approximately 13,200 missing incidents involving children in care. The true figure might be higher—some local authorities don't distinguish between "missing" and "away without authorisation," potentially leading to a 13% undercount of one category and 36% undercount of the other.

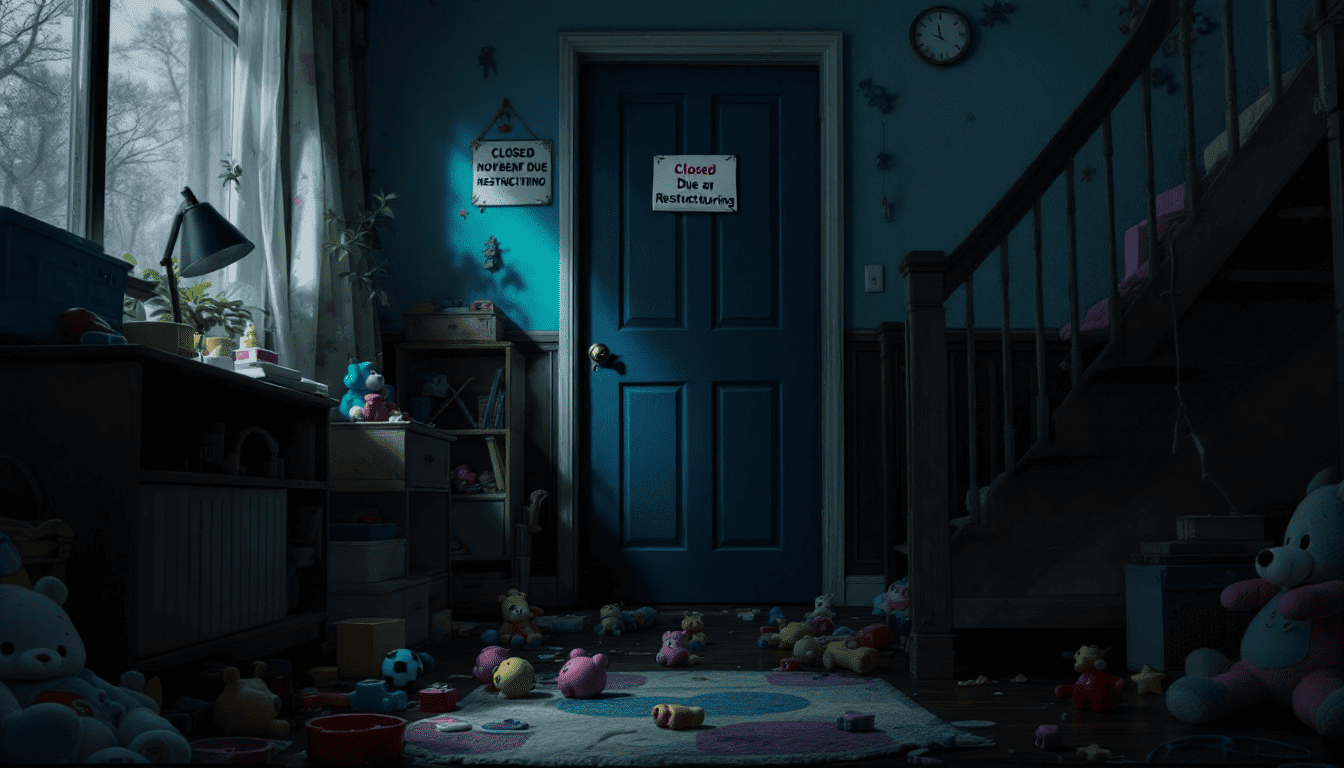

Former resident Ezra Quinton, now 20 and working for the care leavers' charity Become, remembers being moved to a different home every few months after entering care aged nine. Originally from Greater Manchester, he found himself shuffled across the country, often many miles from where he originally lived. "I do not know where the money is being spent," Quinton told the BBC, recalling smashed windows and broken glass in the showers of one home. "Some children have said to us in the past 'we actually don't know where we are on a map'," former Children's Commissioner Anne Longfield explained. "And 'we're so used to being moved, we don't even unpack our bags'."

The Council Bankruptcy Crisis

The spiral works like this: demand for children's residential care rises post-pandemic. The number of children in care with complex needs increases. Local authorities must legally provide placements. But they've closed their own homes over decades of austerity, outsourcing provision to private companies. Now they compete in an undersupplied market where providers can cherry-pick the children they'll accept based on profit margins.

Fees rise above inflation. Councils have no choice but to pay. Children's services spending jumped 16% in just the first half of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022. The County Councils Network reported children's services accounted for £319 million of the £639 million overspend facing county authorities in 2023-24—fully half of the deficit outside councils' control.

By autumn 2024, one in four councils said they were likely to apply for emergency government bailout agreements to stave off bankruptcy in the following two years. An unprecedented 18 councils received Exceptional Financial Support in February 2024 to meet their legal duty to balance budgets—permission to use capital funds from borrowing or asset sales to plug day-to-day spending gaps. This approach loads struggling councils with further debt whilst potentially undermining future capital programmes.

The Local Government Association calculated councils faced a £2.3 billion funding gap in 2025-26, rising to £3.9 billion in 2026-27. Special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) deficits compound the crisis. County and rural unitary authorities accumulated £2 billion in SEND deficits by 2024, projected to reach £2.7 billion by the end of 2025. These deficits are currently kept off budget books through an accounting method called the "statutory override," due to expire in March 2026.

If that override expires without government intervention, 26 of 38 county and rural unitary authorities would risk bankruptcy before 2027—including 18 authorities who would become insolvent overnight. Only four councils believe they can remain solvent by decade's end if SEND deficits transfer to revenue budgets. Considering only six councils in all of England declared bankruptcy in the previous ten years, this represents potential systemic collapse.

Birmingham issued a Section 114 notice in August 2023—Europe's largest local authority effectively declaring bankruptcy. Nottingham followed in November 2023, its Chief Finance Officer unable to deliver a balanced budget due to a £23 million overspend driven by increased demand for children's and adult social care, rising homelessness, and inflation. Woking, Croydon, Slough, Thurrock—the list of failed authorities grows whilst private equity firms extract profit from the same social care costs driving councils to ruin.

The Political Vacuum

No major party wants to confront the private equity sector directly. Labour promised to tackle "excessive profits" and threatened a profit cap if voluntary measures failed. Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warned in 2024 that vulnerable children had become "cash cows" for private equity groups. The Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill introduced in December 2024 included provisions to improve financial oversight.

But the measures are tepid, the timeline glacial. Draft legislation arrived in December 2024. Improved cost transparency and market oversight won't arrive until 2028-29. Meanwhile, councils compete in a dysfunctional market, children suffer in inadequate placements, and private equity firms continue extracting double-digit returns.

The Conservatives proved equally unwilling to act during their 14 years in power. When pressed in December 2023, then-Levelling Up Secretary Michael Gove blamed council "mismanagement" for bankruptcies—ignoring the structural funding crisis and spiralling social care costs. Ministers promised action but delivered delay. The Independent Care Review chaired by Josh McAlister called for a windfall tax on "indefensible" private children's home profits. Nothing happened. McAlister became an education minister himself in 2024, inheriting the same broken system he'd criticised.

Liberal Democrats highlight the issue in opposition but lack the political weight to force change. The Scottish and Welsh governments have both committed to moving away from for-profit provision in children's social care—a model England's political establishment refuses to contemplate despite mounting evidence of market failure.

Behind the scenes, private equity's influence runs deep. These firms manage institutional money—pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds. They employ sophisticated lobbyists, cultivate relationships across the political spectrum, frame their work as providing essential services whilst councils retreat. The sector's trade bodies emphasise regulatory compliance, point to "good" Ofsted ratings, argue that profit enables investment and service improvement.

Some small private providers genuinely provide decent care and operate on modest margins. Sara Milner, who established Cherry Wood children's home in Surrey after a career in local authority care, told the BBC that staffing accounts for 80% of costs and her fees reflect direct outlays. These operators are not the problem. The problem is structural—a market where supply shortages enable the largest providers to extract extraordinary profit margins whilst outcomes for children deteriorate.

Where the Money Goes

Follow the pound. Councils pay £318,400 annually for an average placement. For children with complex needs, costs reach £3.3 million per year. Where does this money go?

Staff wages represent the largest cost, but private care homes consistently pay poorly. Agency workers cycle through positions, turnover remains high, continuity suffers. Training is often inadequate. At the Hesley homes, criminal record checks weren't signed off for some staff for up to six months after they started working with vulnerable children.

Between 2023 and 2024, 22% of all children's homes in England had no registered manager in post. Many operated with managers not registered with Ofsted, which can affect inspection judgements. The West Midlands had the highest proportion of vacant registered manager positions at 28%. 12% of all children's homes had no manager at all.

Private equity-backed companies are typically loaded with debt—often expensive loans to hedge funds via holding companies in offshore jurisdictions. When care companies are bought out, these arrangements disappear from public scrutiny. If such loans turn bad, taxpayers pick up the pieces. The residential care market has borrowed £7 billion. Debt interest payments account for 16% of fees charged by the 26 largest care home providers.

What remains flows to owners and investors. The profit margins—22.6% on average for the largest 15 providers between 2016 and 2020—dwarf returns in most industries. Private equity firms structure ownership through complex chains of subsidiaries. CareTech's structure involves 12 organisations for 220 homes. Keys uses 25 organisations for 156 homes. Money flows upward through management fees, advisory fees, licensing arrangements, rent payments to related entities. By the time it reaches ultimate beneficial owners, the trail has been obscured.

Oxford University research found for-profit providers are "statistically significantly more likely to be rated of lower quality than both public and third sector services." The 10 largest providers made more than £300 million in profits in one year alone. Profits among the top 20 providers amount to 20% of their income. BuzzFeed News analysis using March 2018 inspection data showed 19% of private care homes were rated "inadequate" or "requires improvement"—worse than homes run by nonprofits (16%) and local governments (15%).

Useless Quangos Fail Again

Ofsted bears responsibility for the regulatory failure. The regulator received more than 100 reports of concern at Hesley's Doncaster homes, plus 40 serious incident notifications, over three years. Staff whistleblowers reported abuse. Yet the homes retained "good" ratings until autumn 2022.

Chief Inspector Amanda Spielman admitted:

We acted in response to concerns [but] we worked slower than we should have to recognise the pattern of abuse.

You think?

Homes are rated based on compliance with regulations, not outcomes for children. A facility can be rated "good" whilst children experience multiple placements, go missing repeatedly, suffer restraint abuse, leave care with minimal qualifications and bleak prospects. Between 2018 and 2021, 588 children's homes—19.6% of all facilities—were rated "inadequate" or "requires improvement." Most remained open, continuing to receive taxpayer funding.

When homes close, it's often sudden and destabilising. Outcomes First Group, owned by private equity firm Stirling Spring Capital Partners, shut 28 children's homes in 2023 with short notice. The company cited recruitment pressures and said decisions were made with local authority agreement. But the impact on dozens of children was immediate—another move, another placement, another school, more instability for youngsters who deserve safety and continuity.

The Local Government Association, Association of Directors of Children's Services, and Ofsted all called for tighter market control following the Outcomes First closures. "Such closures are one of the reasons the Local Government Association has been calling, for some years, for far better oversight of large providers," said an LGA spokesperson. The calls went unheeded. No major regulatory changes followed.

The Local Government Association requested a CMA inquiry into the children's social care market in 2021. Josh McAlister's independent review supported the call. But the CMA has limited powers and even less political backing to challenge an industry worth £3 billion annually to private interests with substantial lobbying capacity.

The International Money Dimension

Private equity involvement in children's services isn't unique to England. Across Europe and North America, elder and social care services have been colonised by private firms backed by institutional investors. The UK children's home market alone is worth £6.5 billion annually. The adult social care system costs £22 billion per year. These are attractive targets for private equity seeking stable, government-backed cash flows.

But the consequences are stark. Four out of five of the largest adult care homes in England are owned by private equity firms, US hedge funds, or billionaires based abroad. These owners use debt, rent, and complex ownership structures to extract money from local economies. Frontline staff work long hours for low pay and little security whilst directors receive huge salaries and shareholders collect dividends.

The private equity model fundamentally conflicts with appropriate care provision. Private equity funds typically operate on 7-10 year investment horizons. They acquire companies using substantial debt, implement cost-cutting and revenue optimisation strategies, then sell to the next buyer or float on public markets. The goal is maximising returns within the investment period, not building sustainable, high-quality care services for vulnerable children across decades.

Loading care companies with debt creates risk. If providers become financially unstable and exit the market suddenly—as happened with adult care home provider Southern Cross in 2011—councils scramble to place children whilst continuity of care collapses. Southern Cross's failure led to a legal duty for the useless Care Quality Commission quango to monitor financial health of the "most difficult to replace" adult social care providers. No such duty exists for children's social care providers, despite housing even more vulnerable populations.

The Path Not Taken

Scotland and Wales offer alternative models. Both devolved governments committed to moving away from for-profit provision in children's social care. The approach prioritises local authority and third-sector provision, invests in foster care and early intervention, treats children's care as a public good rather than a profit centre.

England could expand its own children's homes. The National Audit Office noted secure public children's homes cost £270,000 per year—£48,000 less than the average private placement and a fraction of the £3.3 million charged for complex needs cases. Local authorities could collectively commission places, reducing competition and provider leverage. They could invest in foster care, which costs one-eighth as much as residential care and often delivers better outcomes.

Between 2020 and 2024, foster care households fell 4%—9% excluding kinship care with friends and family. This shortage pushes more children into expensive residential care. A 2022 Ofsted analysis of approximately 113 children in homes found over a third had foster care in their original care plan. Addressing the foster care crisis would relieve pressure on residential care demand.

The government announced a £270 million annual Children's Social Care Prevention Grant across 2028-29, plus £557 million for children's social care reform between 2025-26 and 2027-28. These sums sound substantial but pale against the £3.1 billion spent annually on residential placements alone.

Early intervention—family support, mental health services, youth programmes, poverty reduction—costs far less than crisis management. But such programmes lack private profit opportunity and therefore lack the lobbying constituency that keeps residential care privatised despite manifest failure. The political economy favours extraction over prevention.

Children Are The Victims, Again

The scandal continues because powerful interests benefit from the status quo. Private equity firms extract reliable returns from government-funded placements. Institutional investors enjoy stable income streams. Intermediaries and advisors collect fees. Politicians avoid confrontation with the finance sector whilst mouthing platitudes about protecting vulnerable children.

Meanwhile, Aaron Leafe and children like him pay the ultimate price. Those who survive their time in care often leave with minimal qualifications, unstable housing prospects, and mental health challenges stemming from years of inadequate placements and multiple moves. They are more likely to be out of education or work after leaving care. Their life outcomes demonstrate that the current system isn't merely expensive—it actively fails in its fundamental purpose.

The National Audit Office concluded the residential care system "is currently not delivering value for money, with many children placed in settings that don't meet their needs." Former Children's Commissioner Anne Longfield called the situation "completely dysfunctional" and "broken."

Claire Bracey of Become argued:

This market failure is leading to the most unforgivable failure [for] the futures of the children in our care. Children in care can't wait. Urgent steps must be taken now.

But urgent steps require political courage nobody seems willing to muster. The Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill promises tougher laws and better oversight by 2028-29. That's three to four years away. How many more children will cycle through inadequate placements? How many more councils will go bankrupt? How many more deaths, incidents of abuse, cases of restraint misuse, missing children before the political class finally confronts the private equity childcare scandal?

The arithmetic is straightforward.

- Councils cannot afford £320,000 annual placements when central government funding has been slashed 40% in real terms since 2010.

- Children cannot thrive when profit margins matter more than their wellbeing.

- Private equity firms will not voluntarily sacrifice 22% returns out of civic duty.

Without decisive intervention the scandal will continue.

We know what needs to happen. We know the current system is dysfunctional. We know children suffer whilst private equity profits. What we lack is the political will to choose vulnerable children over financial interests. That is the scandal's true heart—not ignorance, but complicity. Not accident, but design. Not failure to recognise the problem, but refusal to solve it because doing so would offend powerful people with money at stake.

Aaron Leafe's death was preventable. So were the hundreds of incidents of abuse at Hesley's homes. So is the ongoing crisis bankrupting councils whilst children's homes extract extraordinary profit. We have chosen this system. We sustain it through inaction. The question is whether we'll choose differently before more children pay with their futures—or their lives.