The Quiet Bankruptcy Of Local Authorities: 100 Councils on the Brink

Fourteen councils have gone bust since 2018. Over 100 more warn of insolvency by 2027. Social care now devours 70% of budgets whilst libraries close, roads decay, and statutory law becomes unenforceable. This is constitutional breakdown by stealth, and it's time to abolish the councils.

The death of local government is not loud. There are no dramatic announcements, no crowds gathering at town hall steps. Instead, Britain's 300-year experiment in municipal self-governance is ending in a long, bureaucratic whimper—one Section 114 notice at a time.

Since the beginning of 2020, fourteen English councils have issued these notices, the closest thing British law permits to declaring bankruptcy. Seven more are expected to follow within weeks. Yet this headline figure conceals a far graver reality.

According to the Local Government Association's October 2024 survey, one in four councils—representing millions of people—say they will likely require emergency government bailouts to avoid insolvency by 2027. For councils with social care responsibilities, this figure rises to 44%.

The County Councils Network's analysis reveals an even starker picture. When special educational needs deficits are properly accounted for, 26 of England's 38 largest county and rural unitary authorities could face bankruptcy by 2027, with 18 becoming insolvent overnight in March 2026 when current accounting exemptions expire. Only four councils believe they can remain solvent through the end of this parliament.

This is not mere fiscal mismanagement. This is the systematic dismemberment of the British state.

When the Money Stops

The mechanics of council bankruptcy are deceptively simple. A Section 114 notice is issued by the chief financial officer when forecast income cannot meet forecast expenditure. All new spending halts except for statutory services. Councillors have 21 days to produce a recovery plan. Government commissioners usually arrive shortly thereafter, their salaries paid by the failing authority itself—the price of failure, as one councillor put it.

Since 2018, Northamptonshire has issued two such notices. Croydon has issued three. Slough, Thurrock, Woking, Birmingham, and Nottingham have each declared effective bankruptcy. Birmingham City Council—Europe's largest local authority—collapsed in September 2023 under the weight of £760 million in equal pay claims and a failed IT system so broken staff could not produce accounts detailing the council's financial situation.

But bankruptcy is merely the visible symptom. The disease runs far deeper. Adult social care and children's services now consume 65% of the average council budget, up from 57% a decade ago. For county councils, this figure reaches 69% and climbs to 76% for some authorities. When nearly three-quarters of your budget disappears into care services before you've fixed a single pothole or opened a single library, you are no longer governing. You are simply managing decline.

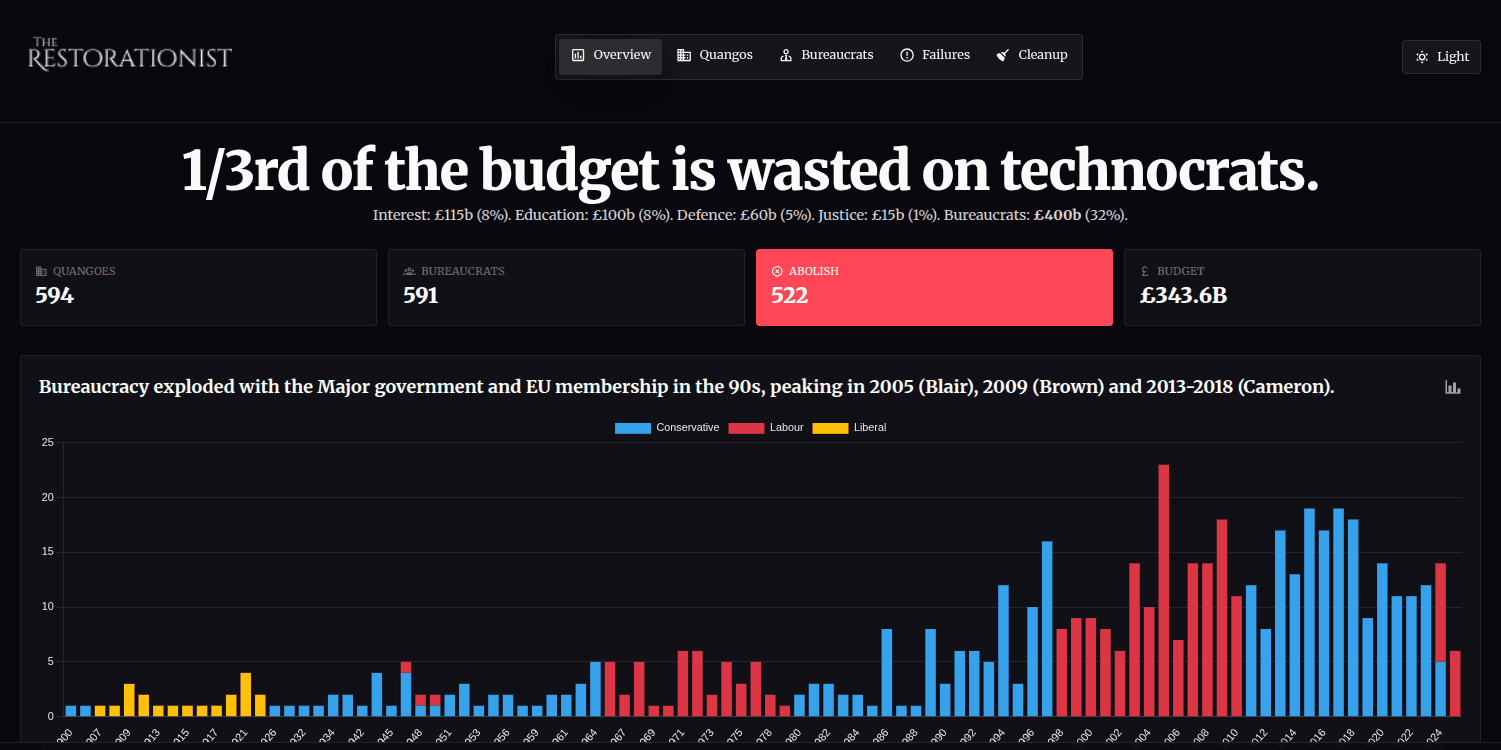

The arithmetic is relentless. Between 2010 and 2020, core spending power for local authorities fell by 17.5% in real terms. Even with emergency Covid grants, funding in 2021-22 remained 10.2% below pre-pandemic levels. The most savage cuts came between 2010 and 2015, when the coalition government imposed reductions totalling £16 billion—roughly equivalent to the entire adult social care budget for 2017-18.

Central government grant funding dropped by 40% in real terms between 2009-10 and 2019-20, from £46.5 billion to £28 billion. By 2023-24, less than 40% of councils' total spending remained for services such as street cleaning, waste collection, and leisure centres. Everything else—libraries, road maintenance, environmental health, planning enforcement—has been reduced to whatever scraps remain after social care has taken its share.

Per-person spending on children's services has doubled since 2013-14, whilst spending on adult social care increased 50%. These two services alone account for 85% of the entire increase in per-head spending over the decade. Councils are spending more in absolute terms but delivering far less in breadth of service.

The Social Care Trap

The trap is simple: social care is a statutory duty. Libraries are not. Road repairs, while technically mandatory, can be delayed. Child protection cannot. So when budgets tighten, councils protect what the law demands and cut everything else.

The result is a vicious spiral. The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services reported 81% of councils expected to overspend their adult social care budgets in 2024/25, up from 72% the previous year, with total overspends estimated at £564 million. Nearly two-thirds of councils overspent on adult social care in 2022-23, with 72% dipping into one-off reserves to cover the gap.

Demand grows inexorably. The number of older people requiring care rises faster than the general population. Working-age adults with disabilities need increasingly complex support. The Children and Families Act 2014 expanded entitlements for special educational needs, and Education, Health and Care Plans increased by 140% from 240,183 in 2014-15 to 575,973 in 2023-24.

Meanwhile, provider markets break down. Care home fees rise to cover the increased National Living Wage—a 6.7% increase in 2025-26 costs the adult social care sector around £1.85 billion. The increase in employer National Insurance contributions announced in Autumn Budget 2024 costs adult social care providers over £900 million. Private providers pass these costs to councils or hand back contracts entirely.

Children's social care presents an even bleaker picture. The number of vulnerable children requiring care has risen dramatically since the pandemic. Placement costs increased 77% in the past decade, whilst broken provider markets mean councils have no choice but to pay spiralling fees. Residential care placements can cost £10,000 per week. When a council has a statutory duty to protect a child, price becomes irrelevant.

The special educational needs crisis threatens to trigger mass insolvency on its own. SEND high-needs deficits were estimated at £2.4 billion nationwide in March 2024 and are projected to reach £5.9 billion when the statutory override runs out in March 2026. For county and unitary councils, deficits will increase from £2 billion to £2.7 billion.

These deficits are currently kept off council balance sheets through an accounting trick called the "statutory override." When this expires in March 2026—just four months away—half of England's largest county and unitary councils will be insolvent overnight.

What Dies When Councils Die

Local government in England performs the overwhelming majority of the state's actual obligations to its citizens. Not the aspirational duties or the political promises—the hard legal requirements.

Under the Children Act 1989 and subsequent legislation, local authorities must safeguard and promote the welfare of children in need, provide services to support families, and undertake enquiries when a child has suffered or is likely to suffer significant harm. When a vulnerable child needs protection, there is no alternative provider. The council must act, or the child remains at risk.

The Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 places extensive duties on local authorities to prevent and relieve homelessness. Around 298,000 homelessness prevention or relief duties were owed to households in 2022-23. Two-thirds of these households either had accommodation secured or were owed a main statutory duty to secure accommodation because they were unintentionally homeless with priority need.

Adult social care responsibilities under the Care Act 2014 are equally non-negotiable. Councils must assess needs, provide care and support, and safeguard vulnerable adults. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 imposes duties towards those who lack capacity to make their own decisions. These are not services councils can choose to reduce below a certain threshold—they are legal obligations backed by judicial review.

Public health, environmental health, waste collection, planning, road maintenance, education support services, local policing support—the list of statutory functions runs to hundreds of individual duties, each with its own legislative foundation. Some can be delayed or delivered minimally. Many cannot.

When Birmingham issued its Section 114 notice, the council announced it would reduce services to the bare legal minimum, focusing on social care and waste collection. Its libraries, children's centres, and 35 council-owned buildings faced closure or sale. The Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, parks services, and Perry Park were all under threat. Residents worried about rising crime from cuts to youth services.

The pattern repeats across every bankrupt authority. Croydon prepared to gut its 13 libraries and nine children's centres. Slough requires continuous financial support until at least 2028. Nottingham's collapse stemmed from increased demand for children's and adult social care, rising homelessness pressures, and inflation—the same pressures every council faces, simply arriving at breaking point sooner.

The Quiet Scandal

The Treasury's position borders on constitutional negligence. Despite overwhelming evidence of systematic collapse, central government has refused to reform the funding model. Instead, it offers occasional emergency bailouts through Exceptional Financial Support—capitalisation directions allowing councils to sell assets to fund day-to-day spending. Eighteen local authorities received £1.4 billion in EFS in 2024-25, compared to just £75.8 million in 2018-19.

This is the fiscal equivalent of selling your house to pay your mortgage. It provides temporary relief whilst accelerating long-term decline. Councils liquidate their capital base—buildings, land, investments—to keep the lights on for another year. When the assets run out, collapse becomes inevitable.

Meanwhile, councils are quietly cutting services below legal minimums without publicising the fact. The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services reported only 6% of directors were fully confident their 2024-25 budgets would be sufficient to meet statutory duties. Fifty-nine percent were "partially confident." Seventeen percent were "not confident."

Think about what this means. The people running adult social care—directors with decades of experience, intimate knowledge of their local systems, and legal obligations they take seriously—are telling you they cannot fulfil the law. Not that it will be difficult. Not that they'll need to be creative. They simply cannot do what statute requires with the resources provided.

The same pattern appears in children's services, homelessness support, and special educational needs. Kent and Hampshire county councils warned in November 2022 they would need immediate financial assistance and long-term sustainability plans from government to avoid bankruptcy, even if services were reduced in "unpalatable" ways.

This is not a funding crisis. This is a constitutional crisis conducted in spreadsheets.

The Failure of Attempted Reform

Local government has not had a multi-year funding settlement since 2015. Councils cannot plan capital investments, cannot restructure services, cannot negotiate long-term contracts when they have no certainty about next year's budget, let alone budgets three or five years hence. The last two Spending Reviews have been one-year settlements, forcing councils to lurch from crisis to crisis.

The "Fairer Funding Review"—promised for years, delayed repeatedly—was meant to address historic inequalities in how resources are distributed between authorities. It has become a running joke, mentioned in parliamentary reports and committee hearings as something perpetually "forthcoming." The longer it is delayed, the more councils collapse under the existing broken system.

Business rates retention was meant to incentivise local economic growth. Instead, it has created a postcode lottery where councils in wealthy areas with strong commercial bases can raise substantial revenue, whilst those in deprived areas with weak business sectors cannot. Council tax—councils' main locally raised income—is both regressive and constrained by government-imposed referendum limits, typically 2-5% per year.

Some bankrupt councils have been granted permission to raise council tax above these limits. Thurrock, Croydon and Slough were allowed increases between 10-15% following their Section 114 notices. But this simply shifts costs to residents already struggling with the cost-of-living crisis, whilst doing nothing to address the fundamental mismatch between statutory obligations and available funding.

The Institute for Government notes councils facing financial difficulties in the first half of the 2010s faced sharp cuts, whilst demand for services—particularly children's and adult social care—increased substantially. Recently, the cost of providing services has risen markedly due to inflation. In response, councils looked to other income sources, particularly commercial property investment.

This strategy has backfired spectacularly. Woking Borough Council will have debts of £2.4 billion by 2026—100 times its annual £24 million budget—including investments in hotels and residential skyscrapers. Thurrock invested £655 million in solar farms through bonds, an investment paused in 2020. Birmingham's equal pay liabilities, some dating back to a 2012 Supreme Court case, were estimated between £650 million and £760 million by March 2023.

The Public Accounts Committee estimates councils have spent £7.6 billion on commercial investments since 2016, with 49 authorities—14% of the sector—accounting for 80% of this spending. Falling commercial property prices, forecast by Moody's to drop 5-15%, are materialising the consequences of past borrowing.

But to blame councils for "risky" investments is to miss the point entirely. Central government encouraged this behaviour. It expanded borrowing flexibility in 2003 and 2011, then cut funding so severely councils had to seek alternative revenue sources. When the gambles failed—as they were always likely to do, given councils lack the expertise to be property speculators—the government pointed fingers at local mismanagement whilst ignoring its own role in creating the incentive structure.

The Path to Constitutional Breakdown

This is how the British state dies: not in revolution or reform, but in the grinding inability to perform basic functions whilst everyone pretends the system still works.

A Section 114 notice is not bankruptcy in the corporate sense. Councils cannot liquidate. They cannot cease to exist. The debts do not disappear. Statutory duties remain on the books. But the council simply stops being able to fulfil those duties, and there is no mechanism in law to deal with this reality.

When a child needs protection from abuse, the Children Act 1989 says the local authority must act. When someone becomes homeless with priority need, the Housing Act 1996 says the local authority must secure accommodation. When an elderly person with dementia needs care, the Care Act 2014 says the local authority must provide or arrange it.

What happens when the local authority has no money? The law is silent. It simply assumes councils will always be able to perform their statutory functions. The possibility they might not was too absurd to contemplate when this legislative framework was built.

We are about to find out what happens when constitutional assumptions meet fiscal reality. The Local Government Association estimates councils face a £2.3 billion funding gap in 2025-26, rising to £3.9 billion in 2026-27—£6.2 billion over two years. Without additional funding, councils will cut the services the law requires them to provide, knowing judicial review is unlikely because everyone understands the money simply isn't there.

Courts might order councils to fulfil their duties, but court orders cannot conjure resources that don't exist. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government could intervene, but intervention merely replaces local councillors with government-appointed commissioners operating under the same impossible constraints. Central government could provide emergency funding, but as current bailouts demonstrate, this merely delays the reckoning whilst accelerating asset depletion.

Or Parliament could legislate to reduce councils' statutory duties, explicitly giving them permission to provide less. This was suggested by Kent and Hampshire councils in their November 2022 letter warning of insolvency. Reduce the legal obligations to match available funding. Make the failure official.

This would at least have the virtue of honesty. It would force Parliament to declare publicly which vulnerable children will no longer receive protection, which homeless families will no longer be housed, which disabled adults will no longer receive care. The current approach—allowing councils to quietly cut below minimums whilst maintaining the fiction of legal compliance—is more politically convenient but constitutionally corrosive.

What Comes Next

The March 2026 deadline for SEND accounting looms. When the statutory override expires and billions in deficits land on council balance sheets, the current trickle of Section 114 notices will become a flood. Half of England's largest councils could declare bankruptcy simultaneously.

The government has promised a white paper on SEND reform for autumn 2025, then delayed it. It has indicated it will "bring forward further plans" before March 2026. But promises and indications are not solutions. The Public Accounts Committee warned the lack of a government plan for under-pressure local authorities to achieve sustainable financial position is leaving hundreds of councils in financially precarious positions.

Three scenarios seem possible.

First, the government could provide massive emergency funding—tens of billions, not the millions currently offered through EFS—and fundamentally reform how councils are funded to match their statutory responsibilities. This would require political will and fiscal capacity currently absent.

Second, Parliament could reduce statutory duties, explicitly telling councils they no longer need to provide certain protections or services. This would constitute the most significant retrenchment of the welfare state since 1945, but it would at least acknowledge reality.

Third, the system could simply collapse under its own contradictions. Councils continue cutting below legal minimums, residents who know their rights bring judicial reviews, courts order compliance councils cannot achieve, central government intervenes with commissioners who face identical constraints, and the whole apparatus grinds to an undignified halt whilst everyone points fingers at everyone else.

The current trajectory points toward the third option.

Not because it's desirable or even tolerable, but because it requires no one to make a difficult decision. It's constitutional breakdown through institutional inertia.

Local government in England is dying. Not dramatically, but incrementally—one closed library, one unfilled pothole, one vulnerable child whose case worker was made redundant, one homeless family turned away because temporary accommodation budgets are exhausted. The law says these services must be provided. The money says they cannot be. Something has to give.

In a functioning democracy, Parliament would either fund councils adequately or change the law to match resources. Instead, we have a conspiracy of silence. The Treasury knows councils are broke. Councils know they're cutting below legal minimums. Citizens haven't quite grasped that the services they assume exist as a matter of legal right are vanishing.

This is how 300 years of municipal government ends: not with a Section 114 notice in Birmingham or Woking or Nottingham, but with a slow, quiet realisation that the British state can no longer perform the most basic functions we ask of it. We are witnessing the quiet bankruptcy of Britain itself, and no one quite knows how to stop it.