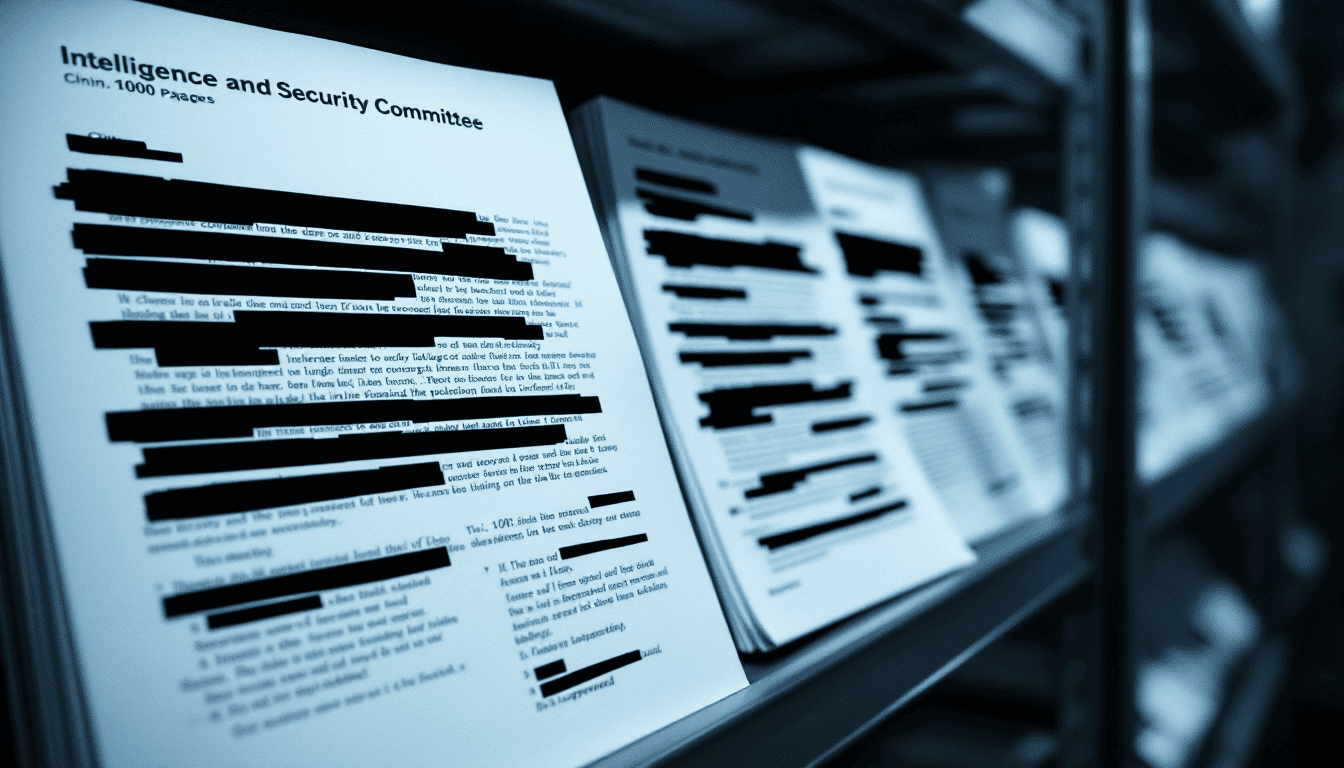

The Report Downing Street Didn’t Want You to Read

When Parliament's intelligence watchdog tries to publish reports on Russia and China, No. 10 interferes and blocks them. When MPs elect their own chair, he loses the whip. When they ask for resources, the Cabinet Office cuts their staff. Ministers suppressed politically sensitive reports.

On 17 October 2019, Britain's Intelligence and Security Committee sent its Russia report to Prime Minister Boris Johnson for final approval before publication. Under longstanding convention, he had ten days to respond. The report examined Russian interference in British politics—including the Brexit referendum and Conservative Party funding from oligarchs with Kremlin connections.

Johnson sat on it for nine months.

When Parliament's ISC finally published the document in July 2020, it revealed the government had made "no effort" to investigate Russian meddling in British voting—despite knowing Moscow interfered in the 2014 Scottish referendum. The delay had served its purpose. The 2019 general election came and went with voters kept in the dark about what their own intelligence committee had discovered.

This wasn't bureaucratic sluggishness. Former ISC chair Dominic Grieve—himself a Conservative MP—called Johnson's excuses "entirely bogus." The intelligence agencies had cleared the report. The Cabinet Office had cleared it. There was no national security reason for delay. Johnson blocked publication because the timing was politically inconvenient.

He was not the first prime minister to do so. Nor would he be the last.

Parliament's Toothless Watchdog

The Intelligence and Security Committee is supposed to be Britain's democratic check on MI5, MI6, and GCHQ. Created by the Intelligence Services Act 1994 and strengthened by the Justice and Security Act 2013, it consists of nine MPs and peers with security clearance who scrutinise the agencies spending billions in taxpayers' money on operations the public never sees.

But there's a catch. Unlike other parliamentary committees, the ISC must submit its reports to the prime minister before publication. Officially, this allows No. 10 to redact material damaging to national security. In practice, it gives Downing Street a veto over anything politically embarrassing.

The pattern is clear. When the ISC investigates something sensitive, the government finds ways to interfere—either by delaying reports, blocking access to information, or making the committee's work impossible through bureaucratic strangulation.

The China Report No One Was Meant to See

The Russia report wasn't an isolated incident. In 2023, the ISC completed its investigation into Chinese espionage and interference in Britain. The inquiry began in 2019. By the time it reached Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in May 2023 for the standard ten-day approval, expectations were low.

They were right to be. Sunak missed the deadline.

The committee issued a rare public rebuke: they were "still seeking answers from the Government as to why confirmation was delayed." When the report finally emerged in July 2023—two months late—it was littered with redactions. Entire sections on Chinese infiltration of critical infrastructure, universities, and civil nuclear energy had been censored at the government's insistence.

The published version still managed to be scathing. It accused ministers of "astonishing" failures, described their approach as "obfuscatory" and "unacceptable." But the full picture remains locked away. The government suppressed the most damaging revelations because Chinese investment in British infrastructure has bipartisan fingerprints. Both Labour and Conservative administrations welcomed Beijing's money. Neither wanted the ISC's findings made public.

When MPs Choose Wrong

Nothing reveals the true state of ISC independence more clearly than what happened in July 2020. After finally reconvening following Johnson's post-election delay, the committee's members gathered to elect their chair. The Conservative whips wanted Chris Grayling—a reliably loyal former transport secretary. Instead, committee members elected Julian Lewis, a Conservative backbencher with an independent streak.

Johnson's response was immediate. Lewis had the Conservative whip withdrawn. His offence? Working with Labour and opposition MPs "for his own advantage"—which is to say, being elected by fellow committee members rather than following orders from No. 10.

Lewis is the second ISC chair in succession to lose the whip under Johnson. The message to MPs serving on the committee could not be clearer: your job is oversight of the intelligence services, but your career depends on Downing Street's approval.

Strangling Funding For Censorship

By May 2025, the situation had deteriorated from political interference into existential crisis. Lord Beamish—the current ISC chair and former Labour MP Kevan Jones—issued an extraordinary public statement. The committee, he warned, might have to "close its doors" unless it received emergency funding.

Since 2013, Britain's intelligence budget has grown by approximately £3 billion. The ISC's budget has remained frozen. In real terms, it has been cut. Meanwhile, the committee's remit has expanded to cover new agencies and capabilities the intelligence community has developed since 2013—including the National Cyber Force, various Cabinet Office intelligence units, and an array of operations for which there is now "no oversight capability."

But the funding crisis is only part of the story. The deeper problem, Lord Beamish revealed, is Cabinet Office control. The ISC sits within the Cabinet Office—the very organisation it is supposed to oversee. Cabinet Office officials manage the committee's staff, control its resources, and have systematically "dismantled" safeguards meant to protect the ISC's independence.

"An oversight body should not sit within, and be beholden to, an organisation which it oversees," Beamish wrote. The statement was remarkable for its bluntness. Constitutional law professors called it "dynamite" and a "significant intervention."

The ISC doesn't normally speak this way. When it does, things are bad.

In 2013, the government agreed the ISC should move out of the Cabinet Office. Twelve years later, it remains there, its staff under the thumb of the people it scrutinises. Lord Beamish disclosed the Cabinet Office had "decimated" the committee's headcount, cutting it to "a skeleton staff" unable to keep pace with an intelligence community spending billions beyond parliamentary scrutiny.

Before the 2024 general election, the Conservative government agreed to an "emergency uplift" in funding. Officials then "declined to implement it." The new Labour government under Keir Starmer has made reassuring noises but taken no action.

The Accountability Vacuum

What does it mean when Parliament cannot oversee the intelligence agencies?

It means MI5, MI6, and GCHQ operate with £3 billion in public funds subject to no democratic scrutiny. It means when they make mistakes—rendition flights, torture complicity, unlawful surveillance—the ISC lacks resources to investigate properly. It means when ministers sign off on questionable operations, no one with access to classified information can hold them to account.

It means the public learns about intelligence failures only through leaks or inquiries held years after the damage is done. The ISC's 2018 report on the 2017 terrorist attacks revealed MI5 had intelligence on the Manchester Arena bomber but failed to act. By the time the committee published its findings, 22 people were dead. How many future failures will never be examined at all?

The ISC has repeatedly complained about gaps in its remit. The Justice and Security Act gives it theoretical power to demand information from the intelligence community. But when the committee sought to scrutinise the government's Afghanistan withdrawal—including the leaked spreadsheet containing names of British intelligence officers and Afghan allies—former Defence Secretary Ben Wallace claimed the matter fell outside the ISC's jurisdiction.

It didn't. The committee oversees Defence Intelligence. Wallace was wrong. But by the time the ISC could push back, the news cycle had moved on.

This is how accountability dies—not through a single dramatic confrontation, but through accumulated delays, withheld documents, and ministerial obstruction so routine it stops making headlines.

Who's Watching the Watchers?

The brutal irony is how little scrutiny this receives. The Russia report delay sparked outrage precisely because Johnson's electoral timing was so obvious. But the China report suppression? The Cabinet Office staffing crisis? These generate one-day stories buried in the inside pages. Most Britons have never heard of the ISC. Those who have assume it functions.

It doesn't.

Paul Scott, professor of constitutional and national security law at the University of Glasgow, observed the ISC's language about Cabinet Office "interference" was striking because the committee almost never speaks this bluntly. When a parliamentary body entrusted with classified intelligence starts using words like "comprehensively dismantled" and "crisis," something has gone seriously wrong.

Yet ministers respond with anodyne statements about "engaging constructively" with the committee and thanking members for their "important scrutiny." Scrutiny they've systematically undermined.

The agencies themselves sometimes complain the ISC is useless—too focused on trivia, not rigorous enough, contributing "little to no new information." But this is circular logic. Starve a committee of resources, block its access to information, and staff it with members dependent on party whips, then complain its reports lack depth. It's the bureaucratic equivalent of tying someone's hands and mocking them for not clapping.

What Was in Those Reports?

We still don't know the full contents of the China report. The redacted sections remain classified. We do know the published version accused the government of astonishing failures on civil nuclear energy, allowing Chinese access to critical infrastructure despite espionage risks. We know it condemned ministers for suppressing earlier warnings about Huawei's role in Britain's 5G network. We know it criticised the inadequate response to Chinese intelligence operations on British soil.

What don't we know? Whatever was damaging enough to be cut entirely.

The Russia report revealed Moscow's interference in British politics was "the new normal." It found Russian money had been "recycled through the London 'laundromat'" and cited oligarchs with Kremlin ties as major Conservative Party donors—nine of them named in the report. It disclosed the government made "no effort" to investigate Russian influence on British electoral infrastructure, despite knowing Moscow interfered in the 2014 Scottish vote.

What we didn't learn—what Johnson's nine-month delay and subsequent redactions ensured we wouldn't learn—was the full extent of Russian penetration into British political life. The report itself noted this gap. Without a proper investigation, the intelligence community couldn't tell Parliament what Moscow had done because ministers never asked them to look.

This is the real scandal. Not that Russia interfered. We knew they did. The scandal is that when Parliament's intelligence committee tried to examine the extent of that interference, the government buried the report for long enough to win an election, then published a version incomplete enough to avoid political consequences.

Redaction As A Political Weapon

Britain is not alone in struggling with intelligence oversight. Every democracy wrestles with the tension between secrecy and accountability. But most don't give the executive such comprehensive power to suppress reports after they're completed.

In Canada, legislation mandates the equivalent committee must be established within 60 days of Parliament sitting after a general election. No Canadian prime minister can simply decline to reconvene oversight for seven months, as Johnson did.

In the United States, Congressional intelligence committees occasionally clash with administrations over classified information. But reports rarely require presidential approval before publication. Congress can—and does—release findings over executive objections.

The ISC's pre-publication review was designed for legitimate security concerns. It has become a political weapon. When a committee investigates Russian interference and the prime minister delays publication until after an election, that's not protecting national security. When a report on Chinese espionage emerges with vast redactions covering policy failures rather than operational details, that's not safeguarding intelligence methods. It's covering up political embarrassment.

The precedent is now set. Future governments know they can suppress ISC reports without serious consequences. They can underfund the committee, staff it with loyalists, and ignore its recommendations. The agencies know parliamentary oversight is largely theatrical—committees may ask hard questions, but lack resources and access to compel answers.

What Comes Next?

Lord Beamish's May 2025 statement was a cry for help. He appealed directly to Starmer, noting the prime minister had "pledged to meet" with the committee and "understand the gravity of the situation." Whether Starmer follows through remains to be seen. The previous government made similar promises.

For the ISC to function, three things must change. First, it needs proper funding proportional to the intelligence community it oversees. An oversight body operating on a frozen budget while the agencies it scrutinises grow by £3 billion isn't oversight—it's pantomime.

Second, it must move out of the Cabinet Office. Situating parliamentary oversight within the executive structure it scrutinises is a constitutional absurdity. Canadian and American intelligence committees manage this separation. So can Britain.

Third, the pre-publication review process needs reform. A deadline for prime ministerial approval—with automatic publication if exceeded—would prevent future Boris Johnsons from weaponising the process. Reports should be presumed publishable unless Downing Street can demonstrate specific, reviewable security harms.

None of this will happen without public pressure. The ISC's dysfunction serves those in power too well. Ministers appreciate having parliamentary oversight they can neutralise through budget starvation and bureaucratic obstruction. The agencies prefer a toothless committee to a properly resourced one. And the public, largely unaware the ISC exists, cannot demand reforms they don't know are needed.

The Documents We Never Read

Somewhere in Whitehall filing cabinets sit the unredacted versions of the Russia and China reports. They contain whatever was too politically damaging to publish. Other reports—investigations killed before completion because the government refused access to information—exist only as classified drafts the public will never see.

We don't know what those reports say. We can guess. More Russian money in Conservative coffers. Deeper Chinese penetration of British infrastructure than admitted. Intelligence failures that cost lives. Ministerial decisions prioritising political convenience over national security.

The reports Downing Street didn't want you to read are the ones that would answer the most important questions. Not technical details about intelligence tradecraft, but the political story of how successive governments allowed hostile states to operate largely unchallenged in Britain because doing something about it would be awkward or expensive or electorally inconvenient.

That's the accountability vacuum. Not a lack of rules or institutions, but a lack of will to enforce them when enforcement becomes uncomfortable. Parliament created the ISC to shine light into secret corners of government. Downing Street responds by controlling the dimmer switch.

Three billion pounds spent without oversight. Reports buried for political convenience. A parliamentary committee starved of resources and independence. This is what passes for intelligence accountability in modern Britain.

And most people have never heard of it.