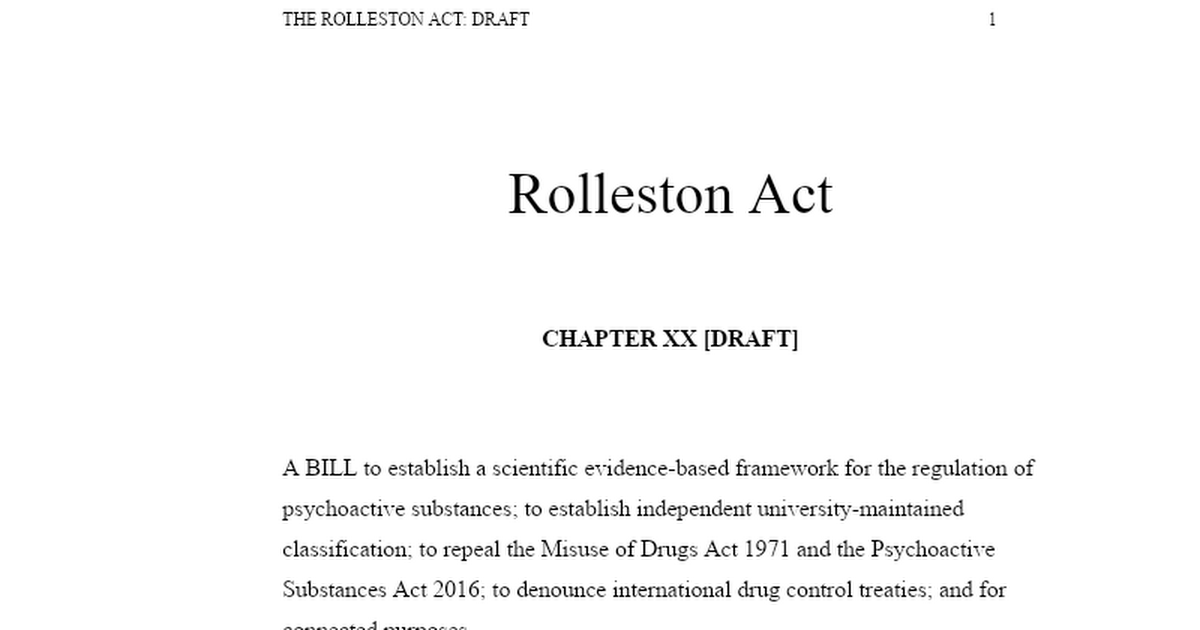

The Rolleston Act: The West's Most Advanced Framework For Alcohol & Drugs

Substances categorised by therapeutic index and addiction risk. Universities maintain an independent peer-reviewed register binding on the government. Apothecaries dispense to citizens 21+ only with severe enforcement. Science replaces politics in drug policy, and Britain breaks free of the US/UN.

The use of psychoactive substances is endogenous to Homo sapiens and cannot be legislated away; but it can be controlled. The laborious, outdated, and scientifically-illiterate Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 have failed. These statutes, products of international treaty obligations and political expediency rather than scientific reasoning, have created more harm than they prevented. They criminalised millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens, enriched organised criminal enterprises, impeded legitimate medical research, and corrupted the relationship between scientific evidence and public policy.

The Rolleston Act represents a fundamental break with prohibition-based drug control and a return to the principles of evidence-based medicine which served Britain well for half a century.

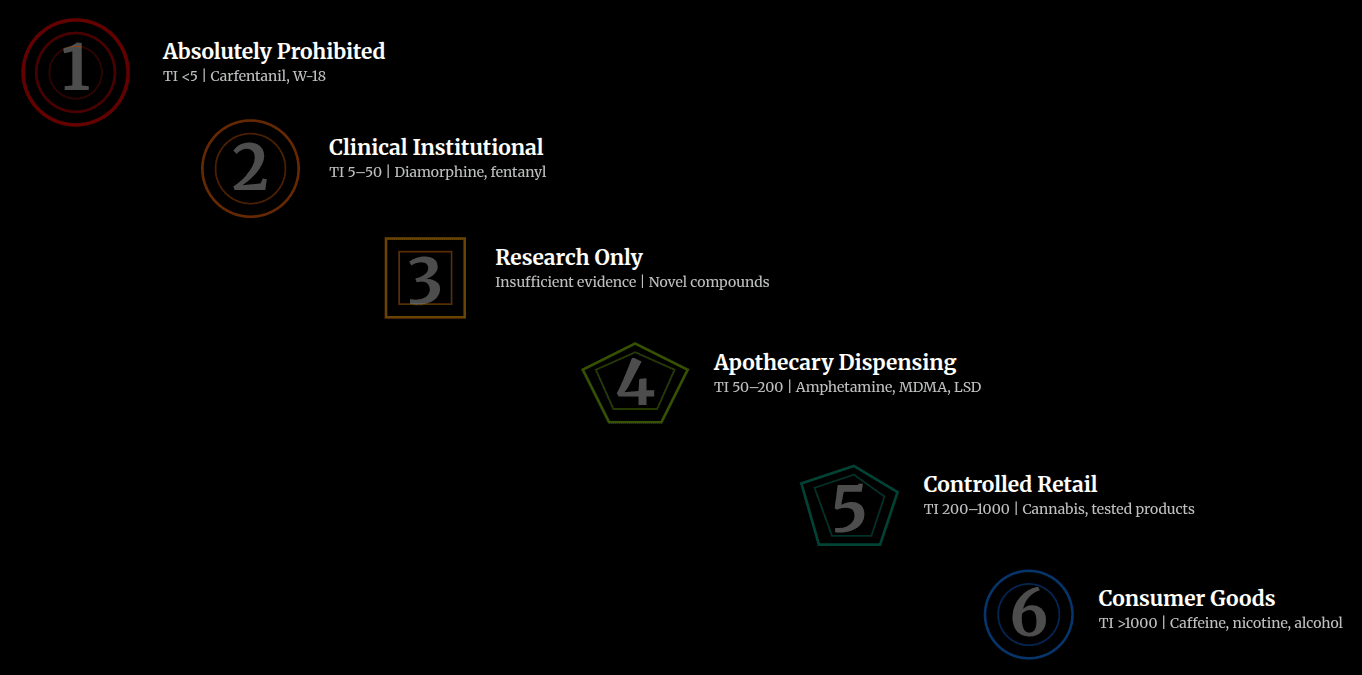

This legislation establishes a six-tier classification framework where every psychoactive substance from carfentanil to caffeine is assigned to one of six regulatory tiers based on measurable therapeutic index and dependency liability. The fundamental innovation lies not in the regulatory treatments themselves but in the removal of classification authority from politicians and civil servants.

Under this Act, classification becomes the exclusive domain of Britain's universities. Those institutions possessing departments of pharmacology, toxicology, chemistry, or related disciplines maintain a public register of psychoactive substances and assign each substance to its appropriate tier through rigorous peer review. Ministers of the Crown are prohibited by statute from interfering with, directing, or attempting to influence these scientific determinations.

The Government remains bound to accept the classifications and may not establish alternative registers or override university decisions through secondary legislation. This represents the most complete separation of scientific classification from political control anywhere in the world.

The apothecary system for Tier 4 substances—those presenting substantial dependency risk but adequate safety margins—reintroduces a model with deep roots in British pharmaceutical history. Modern apothecaries combine pharmaceutical-grade quality control, medical oversight through mandatory hospital affiliation, comprehensive identity verification and quantity restrictions, real-time transaction monitoring through a central database, and immediate exclusion of persons unable to control their consumption.

This approach accepts that demand for psychoactive substances exists whilst implementing every possible safeguard against diversion, exploitation of vulnerable persons, and supply to minors.

The Act concludes with formal denunciation of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961, the Convention on Psychotropic Substances 1971, and the UN Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988. These treaties, negotiated when scientific understanding was primitive by contemporary standards, mandate prohibition-based approaches incompatible with evidence-based public health policy.

Read the draft Rolleston Act written by Alex Coppen in full here (161 pages):

The Rolleston System and Its Displacement

British drug policy once operated on principles utterly foreign to contemporary prohibition. The Rolleston Committee, convened in 1924 to examine the practice of prescribing morphine and heroin to persons dependent on these substances, concluded such prescribing constituted legitimate medical treatment rather than irresponsible indulgence.

The Committee affirmed physicians possessed the clinical autonomy to prescribe opioids for purposes of managing withdrawal symptoms or maintaining persons unable to lead normal lives without such substances. This approach, known as the "British System," recognised addiction as a medical condition requiring medical management rather than a moral failing demanding punishment.

For nearly half a century, Britain maintained low rates of problematic opioid use whilst other nations pursued increasingly punitive prohibition.

Persons dependent on opioids could obtain pharmaceutical-grade morphine or heroin through the National Health Service, eliminating the need for criminal acquisition and preventing the development of a substantial illicit market. Crime associated with drug-seeking behaviour remained minimal. Blood-borne virus transmission through contaminated injecting equipment was negligible. Deaths from adulterated substances or accidental overdose rarely occurred.

The medical profession maintained control over a public health problem, applying clinical judgment to individual cases rather than implementing blanket prohibitions.

This successful model collapsed in the 1960s under international pressure. The United States, having comprehensively failed in its domestic prohibition efforts, sought to export prohibition globally through the United Nations treaty system.

The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961 required signatory states to criminalise production, supply, and possession of designated substances save for narrowly defined medical and scientific purposes. Britain's obligations under this treaty, subsequently reinforced by the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances and the 1988 Convention Against Illicit Traffic, necessitated abandoning the Rolleston principles. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 implemented a UN prohibition framework modelled on American drug control, categorising substances into Classes A, B, and C based on political assessment rather than scientific evidence.

The consequences proved disastrous:

- Problematic drug use increased dramatically.

- Criminal markets flourished.

- Organised crime groups generated enormous revenues from supplying substances the medical profession had previously prescribed legally.

- Persons dependent on opioids faced criminalisation, social exclusion, and barriers to healthcare rather than treatment and support.

- Contaminated street drugs containing unknown adulterants replaced pharmaceutical-grade substances.

- Deaths from overdose and blood-borne virus transmission increased exponentially.

- The criminal justice system became overwhelmed with drug offences whilst achieving negligible impact on supply or demand.

The Rolleston era demonstrated prohibition was unnecessary; the prohibition era demonstrated it was actively harmful.

The Ancient British Apothecary Model

Apothecaries occupied a central position in British healthcare for centuries before the modern separation of prescribing, dispensing, and pharmaceutical manufacturing. These practitioners combined medical knowledge, pharmaceutical compounding expertise, and retail dispensing into a single professional role. They diagnosed ailments, prepared medicines from raw materials, and supplied them directly to patients.

The apothecaries' monopoly on drug supply ensured quality control in an era when adulteration and contamination posed serious risks. Their professional training emphasised pharmacology, toxicology, and the appropriate use of potent substances including opiates, which formed a substantial portion of eighteenth and nineteenth-century therapeutics.

The development of modern pharmacy and medicine gradually displaced this integrated model. The Pharmacy Act 1868 established the pharmaceutical profession as distinct from medical practice. The National Health Service Act 1946 created a system where physicians prescribed and pharmacists dispensed, with little role for the traditional apothecary's combined functions.

Yet the apothecary model possessed advantages this legislation seeks to recapture:

- direct accountability for the appropriateness of supply,

- professional expertise in the properties and risks of potent substances, and

- an established tradition of serving clients' needs whilst exercising professional judgment to prevent harm.

The modern apothecary licensed under this Act differs substantially from both historical apothecaries and contemporary pharmacies.

- Every apothecary must maintain formal affiliation with a National Health Service hospital, ensuring integration with addiction services and emergency medical support.

- A medical director with specialist training in addiction medicine must be present for specified minimum hours weekly and possesses ultimate clinical governance responsibility.

- The premises must meet stringent security requirements including safes capable of resisting forcible entry, comprehensive CCTV coverage, and alarm systems connected to police monitoring.

- All transactions are recorded in a central database enabling real-time checking of quantity limits and exclusion orders.

- No person may purchase Tier 4 substances without presenting a valid British passport or biometric residence permit and undergoing identity verification using technology capable of detecting forged documents.

- Purchase quantities are strictly limited on daily, weekly, and monthly bases to prevent stockpiling and identify concerning consumption patterns.

- The medical director may impose more restrictive limits on individual customers showing signs of problematic use.

- Customers approaching limits must be referred to addiction services through the affiliated hospital.

- Courts may impose exclusion orders—including lifetime bans for serious offences such as supplying to minors or using substances to facilitate sexual offences.

- Every customer receives comprehensive written information on pharmacological effects, health risks, safer use practices, signs of dependency, and available treatment services.

These requirements combine to create a system where pharmaceutical-grade substances are available to adults whilst every possible safeguard operates against harm. It is, quite deliberately, as different from a street corner drug dealer as it is possible to be whilst still providing access to substances people clearly wish to consume.

Universities As Classification Authority

The most radical innovation in this legislation lies not in the regulatory treatments applied to different substances but in the allocation of classification authority to universities rather than government. This decision responds directly to the corruption of scientific advice under the prohibition framework.

The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, established under the 1971 Act to provide independent scientific advice to Ministers, repeatedly found its recommendations ignored when politically inconvenient. Cannabis, MDMA, and psilocybin were maintained in Class A despite scientific evidence supporting reclassification. The Home Secretary rejected expert advice on multiple occasions, prioritising political considerations over pharmacological evidence.

The dismissal of Professor David Nutt from the chairmanship of the Advisory Council in 2009 exemplified this problem.

Nutt, an internationally respected neuropsychopharmacologist, published peer-reviewed research comparing the harms of various psychoactive substances using objective metrics. His findings indicated alcohol and tobacco caused greater harm than cannabis, MDMA, or LSD when therapeutic index, dependency liability, and social consequences were properly assessed. He observed that equestrian sports caused more serious injuries than MDMA consumption.

These statements, whilst scientifically uncontroversial, contradicted the Government's political messaging. The Home Secretary dismissed Nutt for "campaigning against Government policy" and making comments "that damage efforts to give the public clear messages about the dangers of drugs." Several other members resigned from the Advisory Council in protest, recognising the message: scientific advisers must remain silent where evidence contradicts policy.

Universities maintaining the Psychoactive Substances Register possess complete autonomy in classification decisions. They establish governance arrangements, peer review processes, and evidentiary standards amongst themselves without Ministerial approval.

- No Minister may direct, influence, prevent, delay, or otherwise interfere with classifications.

- No Minister may establish an alternative register or amend classifications through secondary legislation.

- The Government remains legally bound to accept classifications published in the register and apply the regulatory treatment corresponding to each tier.

- Politicians who disagree with classifications possess no remedy save persuading Parliament to amend the classification criteria in primary legislation—a process requiring parliamentary debate and public scrutiny rather than Ministerial discretion exercised behind closed doors.

The Government must fund this system adequately through 2 per cent of revenue raised from licensing fees and excise duties. The funding is distributed through UK Research and Innovation, not directly by Ministers, to prevent financial pressure being used as backdoor influence.

Where universities consider funding insufficient, they may apply to the High Court for orders requiring additional funding. Judicial review of classifications is available only on the most limited grounds: bad faith, fraud, undisclosed conflicts of interest, or manifest scientific error such that no body of scientists acting reasonably could have reached the conclusion reached.

Courts may not substitute their own view of scientific evidence for the universities', may not assess weight given to different studies, and may not order substances placed in particular tiers. This deliberately restrictive standard preserves scientific autonomy whilst providing limited safeguards against corruption or gross incompetence. It is, in effect, an absolute firewall between political convenience and scientific truth.

A Scientific Law For Psychoactives

The Act is comprehensive by necessity—replacing five decades of accumulated prohibition legislation requires addressing every aspect of production, supply, possession, and use across six distinct regulatory tiers. Each Part builds upon the foundations established in earlier Parts, creating an integrated system where scientific classification drives legal consequences, where safeguards operate at every stage, and where enforcement targets genuine harms rather than mere consumption.

Part 1: Preliminary Provisions

The preliminary provisions establish foundations for the Act's operation. The legislation takes its name from the Rolleston Committee, deliberately evoking Britain's successful mid-twentieth-century approach to drug policy. Commencement proceeds in stages to ensure practical implementation. The provisions establishing the scientific register take effect six months after Royal Assent, giving universities time to establish governance structures. The most restrictive provisions governing Tier 1, 2, and 3 substances take effect only when the register becomes operational and contains classifications for at least one hundred substances. The apothecary licensing scheme takes effect twelve months after Royal Assent. This phased approach prevents enforcement vacuums whilst allowing time for practical arrangements.

The Act extends throughout the United Kingdom and applies within territorial waters. It covers British ships, aircraft, and offshore installations wherever located. British citizens may be prosecuted for offences committed abroad where such conduct would constitute offences within the United Kingdom, closing jurisdictional loopholes.

The interpretation provisions define terms with scientific precision. "Psychoactive substance" means any chemical compound producing measurable pharmacological effects upon the central nervous system through neuroreceptor binding, neurotransmitter modulation, ion channel alteration, or other mechanisms affecting neuronal signalling. This definition encompasses natural and synthetic compounds, isomers, salts, esters, and derivatives retaining psychoactive properties. It deliberately excludes substances producing only peripheral physiological effects not mediated through central nervous system activity. "Therapeutic index" receives rigorous definition as the ratio of median lethal dose to median effective dose, with both values determined through peer-reviewed protocols and adjusted for species differences. "Dependency liability" encompasses both physiological dependence (tolerance and withdrawal) and psychological dependence (compulsive drug-seeking and loss of control). These definitions employ objective, quantifiable metrics rather than subjective assessments of social harm or moral disapproval.

The parliamentary intent provisions declare frankly what many have long known but few politicians will say: prohibition without scientific basis has failed to protect public health, has created substantial harms through criminalisation, has enriched organised crime, has impeded legitimate research, and has undermined respect for law. Parliament affirms regulation must be founded upon objective scientific evidence regarding therapeutic index, dependency liability, and demonstrable risk rather than cultural prejudice or treaty obligations. Parliament recognises adults possess capacity to make informed decisions regarding consumption provided accurate information and proportionate regulatory frameworks exist. Parliament acknowledges the necessity of protecting vulnerable persons—particularly minors and persons suffering dependency—from exploitation. Most importantly, Parliament declares classification properly constitutes a matter for scientific determination by persons with relevant expertise, and Ministers must not interfere with such determinations. These provisions set the philosophical foundation for everything following.

Part 2: Six-Tier Classification Framework

The six-tier framework divides all psychoactive substances according to measurable scientific criteria. Tier 1 applies to substances presenting extreme and unmanageable hazard—therapeutic index below 5:1, substantial risk of death at typical doses, or profound consciousness alteration rendering users unable to respond to environmental hazards. These substances, including carfentanil and related ultra-potent opioids, present such narrow safety margins that even modest overconsumption proves fatal. They receive absolute prohibition.

Tier 2 applies to substances presenting substantial hazard but possessing legitimate therapeutic value and manageable through specialist medical supervision. These substances have therapeutic indices between 5:1 and 50:1, demonstrate high dependency liability, but can be used safely within controlled institutional settings. Think fentanyl in hospital operating theatres, ketamine for treatment-resistant depression, or methadone for opioid substitution therapy. These remain available, but only where doctors can monitor patients closely.

Tier 3 serves as the default for substances about which insufficient evidence exists for confident classification. Novel psychoactive substances, compounds with conflicting toxicological data, or anything universities cannot confidently place elsewhere automatically receives Tier 3 status. This prevents legal "grey markets" in unclassified substances whilst enabling legitimate research to generate evidence for proper classification. Any unclassified substance is treated as Tier 3 until universities complete their assessment.

Tier 4 applies to substances presenting moderate hazard manageable through controlled dispensing. These substances have therapeutic indices above 50:1 (making accidental death unlikely with basic first aid), demonstrate moderate to high dependency liability with 30 per cent or more of regular users developing compulsive patterns, but present hazards substantially mitigable through quality control, quantity restrictions, identity verification, and harm reduction advice. Cocaine, methamphetamine, MDMA, and pharmaceutical opioids used recreationally fall here. They are available through licensed apothecaries subject to the strict controls described earlier, but they are available.

Tier 5 applies to substances with wide safety margins and low to moderate dependency liability. These have therapeutic indices above 100:1, fewer than 30 per cent of users develop problematic patterns, and adequate safety data demonstrates acceptable risk with basic information provision. Cannabis, psilocybin mushrooms, and kratom would likely fall here. They are available through licensed retail premises subject to age restrictions and quality standards, much like alcohol is sold today, but with rather better quality control and without the aggressive marketing.

Tier 6 applies to substances presenting minimal hazard—therapeutic indices above 500:1, fewer than 10 per cent problematic use rates, extensive historical evidence of safe consumption, and established cultural norms promoting moderate use. Caffeine, theobromine in chocolate, and cannabidiol preparations belong here. These face only ordinary consumer protection legislation and age restrictions where appropriate. No special licensing beyond normal food safety standards applies.

Where a substance's characteristics would place it in different tiers under different criteria, universities must assign the more restrictive tier, applying the precautionary principle. Where different formulations present materially different hazards—oral versus intravenous, low-concentration versus high-concentration—universities may classify different formulations into different tiers. The detailed methodology appears in Schedule 2, but the essential point is this: objective pharmacological properties, not political considerations or cultural prejudices, determine how each substance is treated under law.

Part 3: University-Maintained Scientific Register

Universities possessing relevant scientific departments establish and maintain the Psychoactive Substances Register. They classify each substance according to tier and publish the register electronically with free public access. The universities establish governance arrangements, peer review processes, and procedural rules amongst themselves. No Minister, government department, or public authority may direct, influence, prevent, delay, or otherwise interfere with the register's content, classifications, or governance. This represents complete independence—not advisory independence where Ministers may ignore advice, but operational independence where Ministers cannot touch the process.

Classifications in the register bind all courts, tribunals, law enforcement agencies, and regulatory bodies. They must apply register classifications and possess no power to question, vary, or depart from them. Where a substance lacks classification, it receives automatic Tier 3 status. No person may be prosecuted for conduct relating to an unclassified substance. Courts take judicial notice of the register without requiring proof of authenticity. A certificate from the universities stating a substance's classification is admissible as evidence and presumed accurate unless disproved.

Funding flows from 2 per cent of revenue raised through licensing fees and excise duties, distributed through UK Research and Innovation to prevent Ministerial financial pressure. No conditions may be imposed on funding relating to classification decisions. Where universities consider funding insufficient, they may seek High Court orders requiring additional funding. The prohibition on Ministerial interference is comprehensive: no directing, instructing, requesting, encouraging, suggesting, advising, or recommending regarding classifications. No establishing alternative registers. No amending classifications through secondary legislation. Any attempt at interference is void. Universities may seek High Court injunctions against interference, and persons acting in official capacities who attempt interference commit contempt of Parliament.

Judicial review is available only on the most limited grounds: bad faith, fraud, undisclosed conflicts of interest, or manifest scientific error such that no reasonable scientists could have reached the conclusion. Courts cannot substitute their scientific judgment for the universities', cannot reassess evidence weighting, and cannot order substances placed in particular tiers. They may only declare a classification non-compliant and invite reconsideration. Mere disagreement among scientists, conflicting evidence, or choosing one reasonable interpretation over another provides no grounds for review.

One emergency power exists: where the Secretary of State is satisfied a substance presents immediate and serious threat to public health and harm is likely before universities complete peer review, a temporary Tier 1 order may be made for up to twelve months. Before doing so, the Secretary of State must consult at least three professors from at least three different universities and publish their advice. All supporting evidence must be published. No further emergency order may be made for the same substance. Where universities classify the substance before the order expires, the universities' classification supersedes the emergency order. This provides a safety valve for genuine emergencies whilst preventing abuse through requirements for consultation, transparency, and strict time limits.

Part 4: Tier 1 Absolutely Prohibited Substances

Tier 1 substances face absolute prohibition with no exemptions save for minuscule quantities for forensic analysis. Producing, supplying, or possessing these substances constitutes serious criminal offences reflecting the extreme hazard they present. Production carries life imprisonment on indictment, with mandatory minimum ten years where commercial purposes are proved. Supply or being concerned in supply likewise carries life imprisonment. Simple possession carries up to seven years on indictment or twelve months on summary conviction. Importation and exportation carry life imprisonment.

The Act provides defences for possession: not knowing and having no reason to suspect the substance was Tier 1, taking reasonable steps to destroy or deliver the substance to police upon discovery, or involuntary possession where the substance was placed in one's possession without knowledge or consent. These defences recognise situations where innocent persons might inadvertently come into possession. But they are narrow defences requiring positive proof by the defendant.

Possessing equipment for production of Tier 1 substances with knowledge they are intended for such production carries fourteen years imprisonment. This targets the infrastructure supporting production before actual manufacture occurs. Where equipment, materials, and circumstances permit only one reasonable inference—intended Tier 1 production—courts may draw such inference unless the defendant provides credible explanation.

The prohibition on exemptions is absolute. No licence, authorisation, or exemption may be granted for research purposes, medical purposes, religious purposes, cultural purposes, or any other purpose. The sole exception permits possession of up to 100 milligrams by university or research institution affiliates for analytical or forensic research, under stringent conditions including secure storage, security-vetted access, detailed handling records, and prohibition on human or animal administration. This exception serves legitimate forensic science whilst preventing any broader exemptions. Tier 1 substances present such extreme hazard that even supervised research with human subjects cannot be justified. The absolute prohibition admits no further exception, and no court may create, recognise, or enforce any exemption not provided in the Act.

Part 5: Tier 2 Clinical Institutional Use Only

Tier 2 substances require specialist medical supervision but possess legitimate therapeutic value. They are available only within NHS or registered private hospitals, specialist addiction clinics, and palliative care facilities. These institutions apply for licences from the Secretary of State, demonstrating security meeting standards for controlled drugs, qualified and registered medical and nursing staff, protocols for prescribing and administering, comprehensive record-keeping systems, and arrangements for regulatory inspection. The Secretary of State maintains a published register of licensed institutions.

Licences carry conditions: secure custody in accordance with requirements, monthly stock reconciliation with discrepancy investigation, 24-hour reporting of loss, theft, or suspected diversion, records identifying every patient and recording quantities supplied with clinical justification, and administration only under medical practitioner supervision. The Secretary of State may vary conditions on 28 days' notice or immediately where urgent risk exists. Licences may be suspended or revoked for breaches, inadequate security, evidence of diversion, or risk to public safety. Institutions may appeal refusal, variation, suspension, or revocation to the High Court, but suspension or revocation remains effective pending appeal unless the court orders otherwise.

Only medical practitioners on the specialist register, dentists for specified substances, and nurse independent or supplementary prescribers for specified substances may prescribe Tier 2 substances. They may prescribe only where employed by or holding practising privileges at a licensed institution, only for substances the institution is authorised to hold, only where clinically necessary, after informing patients and obtaining informed consent, and with appropriate monitoring arrangements. Prescriptions must specify patient details, substance and quantity, dose and frequency, route of administration, clinical indication, treatment duration, and be signed and dated. No prescription may exceed 28 days without review confirming continued clinical necessity. Prescribers must maintain records including clinical assessment justifying the decision.

Corrupt prescribing—prescribing without genuine clinical need, motivated by financial gain or personal advantage, or knowing the substance will be diverted—carries fourteen years imprisonment and triggers fitness to practise proceedings with a view to erasure from the professional register. Negligent prescribing falling seriously below expected standards, including inadequate assessment, excessive quantities, or failure to monitor, leads to disciplinary proceedings before the relevant regulatory body and potential suspension or erasure. These provisions recognise physicians and other prescribers hold positions of trust and their abuse of that trust warrants severe consequences.

Unauthorised possession by persons without valid prescriptions carries up to five years imprisonment. Diversion from clinical settings by employees—through theft, deception, forgery, or other dishonest means—carries fourteen years imprisonment, with strict liability regarding removal from the institution save where independent testing failed to detect defects through no fault of the employee. Supply to unauthorised persons from licensed institutions carries fourteen years imprisonment. These offences target the weak points in the system: corrupt prescribers, thieving employees, and institutional supply to wrong persons. The penalties reflect the seriousness of breaching trust within medical settings.

Part 6: Tier 3 Research Only

Tier 3 substances are available only for bona fide research conducted by approved institutions. Universities, research institutes funded by research councils, organisations conducting research of international standing, and pharmaceutical companies conducting MHRA-approved clinical trials may apply for research licences. Applications must include research protocols detailing purposes, substances, quantities, methodology, and expected outcomes. Where human administration is involved, applications must include ethics approval from recognised committees, informed consent arrangements, medical supervision arrangements, adverse event protocols, and insurance or indemnity arrangements. Applications must demonstrate security meeting specified standards and researchers possessing appropriate qualifications.

Research licences carry conditions: substances used only for approved protocol purposes, no human administration without ethics approval and informed consent, secure storage meeting specified standards, detailed acquisition and disposal records, and disposal of unneeded substances according to approved protocols. The Secretary of State may vary conditions on 28 days' notice, and may suspend or revoke licences for breaches, non-compliance with protocols, withdrawn ethics approval, or risk to participant or public safety. Institutions may appeal refusal, variation, suspension, or revocation to the High Court.

Ethics review committees of the Health Research Authority, university research ethics committees, NHS research ethics committees, and the Animals in Scientific Procedures Committee are recognised. The Secretary of State maintains a published list of recognised bodies. Where research involves human administration, comprehensive requirements apply: written informed consent after providing information on substance nature, risks, research purpose, and right to withdraw; risk assessment identifying reasonably foreseeable risks and mitigation measures; medical supervision throughout intoxication and such period thereafter as the ethics committee considers necessary; emergency management protocols including adverse reaction procedures; and insurance or indemnity providing compensation for harm. Ethics committees must apply the precautionary principle, approving research only where benefits outweigh risks, risks are minimised so far as reasonably practicable, and alternative methodologies are not reasonably available.

Institutions are encouraged to publish findings in peer-reviewed journals, particularly findings contributing to understanding of pharmacological properties, toxicological profiles, or dependency liability. Publication includes negative results, recognising their value in preventing duplication and providing complete evidence. Nothing requires publication where it would compromise intellectual property, commercial confidentiality, or participant privacy. Where serious adverse events occur—death, life threat, hospitalisation, persistent disability, or other medical significance—institutions must report to the universities maintaining the register within 24 hours, to the ethics committee, and to MHRA where required. The universities maintain an adverse events database informing classification decisions. Failure to report breaches licence conditions and may result in suspension or revocation.

Unauthorised possession of Tier 3 substances carries up to five years imprisonment, with defences for personal use in small quantities where the person did not supply others and did not know possession was unlawful, or where the person did not know the substance was Tier 3. Supply without research licence carries ten years imprisonment. Unlawful human administration outside approved protocols carries fourteen years imprisonment, with higher sentences where death or serious injury results. These provisions recognise Tier 3 substances present uncertain risks justifying research-only status whilst prohibiting recreational use until proper classification occurs.

Part 7: Tier 4 Apothecary Dispensing

Tier 4 substances—those presenting moderate hazard manageable through controlled dispensing—are available through licensed apothecaries combining pharmaceutical quality, medical oversight, comprehensive safeguards, and customer accountability. Only bodies corporate or registered partnerships may hold apothecary licences. Directors and partners must be fit and proper persons free from convictions for dishonesty or drug offences. Applicants must demonstrate financial solvency of £500,000 through audited accounts or guarantees, insurance covering public and professional indemnity of £10 million, and security assessments of proposed premises. Most critically, applicants must enter formal affiliation agreements with NHS hospitals providing practising privileges for the medical director, referral pathways to addiction services, emergency medical support, and clinical governance oversight.

Every apothecary must employ a medical director registered with the General Medical Council, possessing five years' clinical experience and training in addiction medicine. The medical director must be present minimum 20 hours weekly, oversees all transactions, assesses customers with concerning patterns, makes referral decisions, decides temporary exclusions, trains staff in harm reduction, and liaises with the affiliated hospital. The medical director cannot be dismissed without prior written consent from the Secretary of State. Where affiliation agreements terminate without renewal, licences automatically suspend until new agreements are established, and revoke if no agreement is established within 28 days.

Premises must meet stringent requirements: safes resisting forcible entry for one hour with tamper alarms, CCTV covering all storage, transaction, entrance, and external areas with 90-day retention, alarm systems connected to police monitoring, consultation rooms providing privacy for medical discussions, age verification technology reading biometric documents and verifying authenticity, and no external advertising or signage beyond discreet identification. Geographical restrictions prohibit licences within 500 metres of schools, within town centre primary retail zones, or within 200 metres of other apothecaries. Before granting licences, the Secretary of State must consult local authorities, commission community impact assessments, and consider effects on crime, public health, amenity, and vulnerable populations.

Eligibility requires British citizenship or indefinite leave to remain, age 21 or over, and absence of exclusion orders. Customers must present valid UK passports or biometric residence permits—the only acceptable identification—and undergo biometric verification. Apothecaries must check the Central Exclusion Register in real time before every transaction. Where verification fails or exclusion orders exist, supply is prohibited absolutely with no discretion to override. Daily, weekly, and monthly quantity limits prevent stockpiling and identify problematic consumption. The Central Apothecary Database aggregates purchases across all apothecaries, preventing evasion through multiple premises. Medical directors may impose more restrictive limits on individual customers with concerning patterns.

Apothecaries must provide comprehensive written information on first purchase of each substance: pharmacological effects, acute and chronic health risks, interactions with other substances, harmful pattern avoidance, safer administration routes, overdose avoidance techniques, overdose recognition, naloxone availability and use where relevant, warning signs of dependency (tolerance, unsuccessful reduction attempts, continuation despite consequences, substantial time or resources devoted to obtaining and using), and details of treatment services including affiliated hospital addiction services and national helplines. Failure to provide information constitutes an offence and may ground civil liability. Consumption within 50 metres of apothecary premises is prohibited. Supply to intoxicated customers is prohibited.

The Central Apothecary Database records all transactions using encrypted customer identifiers preventing identity determination save for verification or law enforcement investigation. Transactions must be recorded within 60 seconds. The system prevents completion where quantity limits are reached or exclusion orders exist. Data is encrypted in storage and transmission, retained seven years then securely deleted, and accessible only for verification, recording, limit checking, exclusion register checking, and investigating specific offences under court orders. Customers may request copies of their data. Data may not be disclosed to immigration, tax, or other authorities for unrelated purposes save where court orders require or serious crime unrelated to substance use necessitates. Anonymised aggregate data may be provided to researchers for public health monitoring and epidemiological research.

Medical directors must refer customers to addiction services where they purchase at or near maximum limits regularly, show signs of intoxication when attending, demonstrate physical deterioration, or request assistance with reducing or ceasing consumption. Referrals are supportive and non-punitive, offering assessment within 14 days and evidence-based treatment including substitution therapy, psychological interventions, and mutual aid. Medical directors may impose temporary exclusion orders up to six months where continued consumption presents serious health risk, after explaining reasons and affording opportunity to respond. Customers may appeal to independent medical panels convened by affiliated hospitals. During exclusions, customers receive addiction treatment information and referral offers. Exclusions are recorded in the Central Exclusion Register.

Courts may impose exclusion orders when sentencing for proxy purchase, supplying to minors, violence or threatening behaviour at apothecary premises, or fraud evading quantity limits. Orders may last one to ten years or lifetime. Lifetime exclusions are mandatory for supplying to minors, using substances to facilitate sexual offences, or manslaughter where the unlawful act consisted of supplying Tier 4 substances. Breaching exclusion orders carries up to two years imprisonment. The Central Exclusion Register records all orders and prevents supply to excluded persons.

Apothecary offences carry severe penalties. Breach of licence conditions results in immediate revocation save for trivial immediately rectified breaches, fines up to £500,000 or two years imprisonment, and five-year director disqualification for convicted directors. Supply to ineligible persons (under 21, non-citizens without indefinite leave, or excluded persons) is strict liability regarding ineligibility save where all verification procedures were followed and documents were of such quality they could not reasonably be detected as false, carries fourteen years imprisonment, and results in automatic licence revocation with no further licence to the same applicant or bodies with common directors or ownership. Supply above quantity limits carries ten years imprisonment and automatic revocation. Failure to provide education materials carries fines up to £10,000. Adulteration or quality failures are strict liability save where independent testing failed to detect defects through no fault of the apothecary, carry fourteen years imprisonment, and result in automatic revocation. Failure to record transactions or completing transactions despite database prohibitions is strict liability with no reasonable excuse defence, carries five years imprisonment, and results in automatic revocation. Creating false records or manipulating records to enable customers to evade limits carries ten years imprisonment and automatic revocation.

Apothecaries are strictly liable in civil law for harm from supply to ineligible persons, adulterated or substandard substances, or failure to provide education materials, with liability extending to compensation for personal injury including death and consequential financial losses without limit. Insurance covering £10 million minimum is mandatory, and failure to maintain insurance results in immediate revocation. These provisions create comprehensive accountability where profit cannot be privatised whilst harm is socialised.

Part 8: Tier 5 Controlled Retail

Tier 5 substances—those with wide safety margins and low to moderate dependency liability—are available through licensed retail premises subject to age restrictions and quality standards. Retailers apply to local authorities for retail premises licences with fees between £500 and £5,000. Local authorities grant licences where applicants are fit and proper persons without recent drug supply, dishonesty, or violence convictions, and without unresolved bankruptcy or voluntary arrangements, and where premises meet structural and operational standards prescribed in regulations. Applicants submit operating plans detailing staff training, inventory control, identity verification, complaint handling, and compliance monitoring. Local authorities may attach conditions promoting licensing objectives: protecting children, preventing crime and disorder, promoting public safety, and preventing public nuisance. Conditions may relate to opening hours, proximity to schools, security including CCTV and secure storage, record-keeping, staff supervision, and advertising restrictions. Licences remain in force three years unless surrendered or revoked. Local authorities maintain published registers of licensed premises.

Supply to persons under 18 is prohibited. Where reasonable cause exists to suspect purchasers may be under 25, retailers must require photographic identification bearing date of birth—passports, photocard driving licences, national identity cards, or other prescribed forms. It is a defence to prove all reasonable steps were taken to verify age and reasonable belief existed the person was 18 or over. Supply to minors carries up to ten years imprisonment. Failure to take reasonable verification steps carries fines up to level 5.

Substances must meet purity standards prescribed in regulations specifying maximum adulterants, contaminants, heavy metals, pesticide residues, microbiological contaminants, and other impurities presenting health risks. Labelling must accurately state substance identity in comprehensible terms, net mass or volume, psychoactive constituent concentrations where not in natural form, unique batch identification numbers permitting traceability, and warnings regarding safe consumption, potential adverse effects, interactions, and circumstances where consumption should be avoided. Where substances present poisoning risks to children, packaging must incorporate child-resistant features complying with British Standards and be opaque preventing children viewing contents. No claims may be made regarding therapeutic benefit in relation to disease, disease prevention, performance enhancement beyond recognised psychoactive effects, or safety, unless substantiated by peer-reviewed clinical evidence in recognised scientific journals. Claims made by implication through context, presentation, or circumstances are prohibited where reasonable consumers would understand such claims were being made. Violations carry up to two years imprisonment or fines up to level 5 depending on severity.

Restrictions on retail supply prohibit sale from temporary structures, mobile units, market stalls, vehicles, or premises lacking fixed permanent locations. Distance selling where customers are in the United Kingdom at purchase—mail order, telephone, internet, email, or any other distance communication—is prohibited, though advance orders for collection following age verification are permitted. Advertising may not target or appeal to persons under 18, associate consumption with enhanced performance or endurance, associate consumption with social success or sexual attractiveness, encourage excessive consumption or consumption in risky circumstances, or make prohibited claims. Publishing, displaying, or distributing advertisements within 100 metres of schools, child services premises, or children's recreational areas is prohibited. Display within premises must prevent visibility from public highways, public places, or locations accessible to minors, achieved through screening, partitions, dedicated adult-only rooms, or other means. Violations carry up to two years imprisonment or fines up to level 5.

Home cultivation of up to four plants by persons 18 or over for personal consumption only is lawful. Plants must not be supplied to others, must be positioned preventing visibility from public areas or communal building areas, and personal consumption means consumption only by the cultivator. Cultivation using hydroponic systems, excessive artificial lighting, atmospheric control, automated irrigation, or other equipment indicating production capacity exceeding personal requirements is prohibited. Processing equipment including mechanical trimmers, extraction apparatus, concentration equipment, industrial drying systems, commercial packaging machinery, or vacuum-sealing equipment in conjunction with cultivation is prohibited except where retail licences or manufacturing licences are held. Multiple harvests in various curing stages, commercial packaging materials, precision scales under one gramme, customer lists, substantial cash, or communications indicating supply arrangements provide evidence from which courts may infer unlicensed commercial supply. Violations carry the penalties for unlicensed retail supply.

Cultivation must not cause statutory nuisance through odour, noise, light pollution, increased traffic inconsistent with residential character, or antisocial behaviour. Local authorities may serve abatement notices requiring nuisance abatement, prohibition of recurrence, or activity restriction. Where abatement notices are not complied with without reasonable excuse, local authorities may apply to justices for warrants authorising entry and seizure of plants, equipment, and materials. Seized items may be destroyed without compensation. Failure to comply with abatement notices carries fines up to level 5, with further fines up to one-tenth level 5 for each day the offence continues. Tenants must obtain landlord consent before cultivating. Landlords may prohibit cultivation for any reason or no reason. Cultivation without consent breaches tenancies but does not itself constitute criminal offences. Landlords may seek possession or take other civil remedies for breach of covenant. Where cultivation causes damage or creates structural risks, landlords may recover damages in civil proceedings.

Unlicensed retail supply carries seven years imprisonment, with defences for supply between adults without consideration in quantities reasonably attributed to single-occasion personal consumption as specified in regulations. Supply to minors carries ten years imprisonment, with defences for taking all reasonable steps to verify age and reasonably believing the person was 18 or over. Cultivation exceeding four plants for personal consumption carries six months imprisonment or fines up to level 5. Cultivation for commercial supply carries ten years imprisonment. Courts may order forfeiture and destruction of all plants, equipment, and materials used in connection with offences.

Part 9: Tier 6 Consumer Goods

Tier 6 substances—those with extensive safety margins, minimal dependency liability, and long history of safe human use—are subject only to ordinary consumer protection legislation. They remain subject to the Food Safety Act 1990, General Food Regulations 2004, Food Safety and Hygiene Regulations 2013, Consumer Rights Act 2015, Consumer Protection Act 1987, Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, General Product Safety Regulations 2005, and all other consumer protection, product safety, unfair trading, and consumer rights legislation as those enactments apply to consumer goods generally. Local authority trading standards departments, food standards authorities, and other regulatory bodies retain all enforcement authority over Tier 6 substances and enforce compliance using powers conferred by relevant enactments.

Nicotine-containing products including nicotine replacement therapies, electronic cigarettes, and tobacco products remain subject to age restrictions prohibiting supply to persons under 18 pursuant to the Children and Young Persons Act 1933, Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016, and other applicable legislation. Nothing in the Act diminishes, supersedes, or otherwise affects application of existing regulatory requirements or enforcement mechanisms applicable to consumer goods, food products, medicinal products, or any other product categories into which Tier 6 substances may fall.

Ethanol intended for human consumption remains subject to the Licensing Act 2003, Alcoholic Liquor Duties Act 1979, and all other legislation governing production, importation, distribution, retail sale, premises licensing, and taxation of alcoholic beverages. Tobacco products remain subject to the Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016, Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations 2015, Children and Young Persons Act 1933, and all other legislation governing manufacture, packaging, labelling, sale, advertising, and taxation. Nothing in the Act alters application of those enactments to alcoholic beverages or tobacco products.

Parliament acknowledges alcohol and tobacco, whilst meeting certain Tier 6 toxicological criteria regarding therapeutic index and safety margins, have been subject to separate comprehensive regulatory frameworks predating the Act and developed over extended periods to address specific public health considerations. It is not Parliament's intention those frameworks should be displaced or superseded. The Act effects no increase in restrictions applicable to production, distribution, sale, advertising, or consumption of alcohol or tobacco beyond restrictions existing under law immediately before commencement. Classification of ethanol and tobacco products under the Psychoactive Substances Register is maintained for scientific completeness and public information, but such classification does not alter the regulatory regime applicable to those substances, which regime continues being determined by the legislation specified above and not by the tier system.

Where ethanol or tobacco products have been adulterated by adding other psychoactive substances classified in Tiers 1 through 5, such adulterated products are subject to provisions of the Act applicable to the tier of the adulterant substance. Existing regulatory frameworks for alcohol and tobacco do not provide exemption from Act requirements in respect of such adulterants. This closes loopholes where dangerous substances might be added to otherwise lawful products.

Part 10: Transport Offences

Driving whilst impaired by any psychoactive substance classified in Tier 1 through Tier 6 is prohibited. A person commits an offence by driving or attempting to drive mechanically propelled vehicles on roads or other public places whilst ability to drive is impaired through consumption of any psychoactive substance. Impairment means measurable reduction in ability to control vehicles safely or respond appropriately to traffic conditions, road hazards, or other road users. Persons may be convicted if consumption occurred at any time prior to driving such impairment persisted at the time of driving. Conviction carries up to six months imprisonment, fines, or both, and in all cases mandatory disqualification from driving for minimum twelve months.

The Secretary of State may by regulations specify, for any psychoactive substance classified in Tier 4, 5, or 6, concentration limits in blood, urine, or saliva above which persons are deemed unfit to drive. Where such limits are specified, driving or attempting to drive whilst concentration exceeds specified limits constitutes an offence regardless of whether impairment can be demonstrated. This does not apply to persons who consumed Tier 2 substances pursuant to valid clinical prescriptions or administration in clinical institutional settings, provided satisfactory evidence is produced. Conviction carries up to six months imprisonment, fines, or both, and in all cases mandatory disqualification for minimum twelve months. Regulations specifying concentration limits are subject to affirmative resolution procedure.

Causing death of another person by driving whilst in contravention of impairment or specified concentration provisions carries up to fourteen years imprisonment, fines, or both, and in all cases disqualification for minimum two years. Causing serious injury—meaning grievous bodily harm—by driving whilst in contravention carries up to five years imprisonment, fines, or both, and in all cases disqualification for minimum two years. These provisions recognise driving whilst impaired by any psychoactive substance presents serious risks to other road users and warrants severe consequences where death or serious injury results.

Apothecaries dispensing Tier 4 substances must provide customers written warnings approved by the Secretary of State stating consumption may impair driving ability, driving whilst impaired constitutes criminal offences, and specifying minimum periods during which customers are advised not to drive following consumption, determined by reference to known pharmacokinetic properties. Breach of this duty constitutes offences punishable on summary conviction by fines not exceeding level 5, and may be relevant to civil proceedings alleging apothecary negligence including proceedings arising from harm caused by customers who drove whilst impaired.

Constables in uniform may require persons driving or attempting to drive mechanically propelled vehicles to provide breath specimens for preliminary tests where reasonable cause exists to suspect psychoactive substance consumption. Where preliminary tests indicate presence of psychoactive substances, or where constables have reasonable cause to suspect impairment regardless of test results, constables may arrest without warrant and require specimens of blood, urine, or saliva for laboratory analysis. Persons who without reasonable excuse fail to provide specimens when required commit offences carrying up to six months imprisonment, fines, or both, and in all cases disqualification for minimum twelve months. The Secretary of State may by regulations make further provision concerning preliminary testing devices, laboratory analysis procedures, and admissibility of test results. Sections 4, 5, and 5A of the Road Traffic Act 1988 are amended such references to controlled drugs are replaced with references to psychoactive substances classified in Tier 1 through 6, with consequential amendments to testing and evidential procedures set out in Schedule 4.

It is an offence for persons to act as pilots of aircraft or crew members whilst ability to perform those functions is impaired through consumption of any psychoactive substance. It is an offence for persons to act as masters or crew members of ships or vessels whilst ability to perform those functions is impaired. The Civil Aviation Authority and Maritime and Coastguard Agency may make regulations specifying concentration limits for psychoactive substances for these purposes, which limits may be stricter than those applicable to road traffic. Conviction carries up to two years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Part 11: Custodial Institutions

Introducing Tier 1, 2, 3, or 4 substances into prisons or other custodial institutions carries up to ten years imprisonment, which sentence is served consecutively to any sentence currently being served. Introduction includes bringing substances into prisons, transmitting by post or courier, throwing over perimeter walls or fences, or causing delivery by any means whatsoever. This applies to prisoners, visitors, contractors, and all other persons whether or not ordinarily present within prisons. Where persons committing these offences are at the time prison officers, prison governors, or other employees of His Majesty's Prison Service, the maximum term increases to fourteen years. Convicted prison staff are dismissed from employment and forfeit pension or retirement benefits.

Prisoners commit offences by having Tier 1, 2, 3, or 4 substances in possession within prisons unless possession is pursuant to valid medical prescriptions administered by prison medical services. Conviction carries orders adding additional days to imprisonment terms, not exceeding 42 days, or alternatively up to two years imprisonment served consecutively to current sentences. Prison governors may require prisoners to provide urine, blood, or saliva samples for ascertaining whether prisoners have consumed any psychoactive substance in contravention. Testing may be conducted randomly, on reasonable suspicion, or upon entry to or release from prison. Refusal to provide samples when lawfully required constitutes disciplinary offences and may result in loss of privileges, segregation, or addition of days to sentences. Testing results are admissible in evidence in proceedings for offences.

Prison governors may require visitors to submit to full body scanner screening prior to entry. Visitors refusing scanning may be refused entry, and such refusal does not constitute breaches of visitor rights. Body scanners must comply with health and safety standards set by the Secretary of State and be operated respecting dignity and privacy. Prison officers may conduct physical searches of visitors including searches of clothing and personal belongings where reasonable suspicion exists visitors are attempting to introduce psychoactive substances. Visitors refusing consent to searches may be refused entry. Prison officers may deploy drug detection dogs to screen visitors and belongings. Vehicles entering prison car parks or delivery areas may be searched without warrant if reasonable suspicion exists they contain psychoactive substances intended for introduction.

His Majesty's Prison Service must ensure addiction treatment services are available to prisoners requesting such services. Treatment services must include medication-assisted treatment, psychological therapies, and peer support programmes, funded from the Psychoactive Substances Healthcare Fund. Harm reduction services including needle and syringe programmes where clinically appropriate may be provided at the discretion of prison medical services and in accordance with public health guidance. Prisoners receiving treatment must be provided continuity of care upon release, including referral to community addiction services and arrangements for ongoing medication where appropriate. These provisions recognise prisons concentrate populations with high rates of problematic substance use, and providing treatment serves both humanitarian and public health purposes.

Part 12: Enforcement Powers

Constables may stop and search persons or vehicles where reasonable grounds exist for suspecting possession of psychoactive substances in circumstances constituting offences. Constables may detain persons or vehicles for such time as reasonably required to conduct searches. Constables may search clothing, bags, and other items in possession or control, and may require removal of outer garments. Exercise of these powers is subject to Code A of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 Codes of Practice, and constables must make written records of searches.

Justices of the peace may issue warrants authorising constables to enter and search premises where justices are satisfied on information on oath reasonable grounds exist for believing offences have been, are being, or are about to be committed on those premises. Warrants authorise constables to enter by force if necessary, search premises and persons found therein, and seize and detain any psychoactive substance, document, record, or other item reasonably believed to be evidence of offences. Warrants remain valid one month from issue.

Constables may seize any substance reasonably believed to be psychoactive substances for enabling analysis. Seized substances must be submitted to laboratories approved by the Secretary of State within 28 days. Analysis results are admissible in evidence provided certificates of analysis are produced in prescribed forms. Where analysis confirms seized substances are not psychoactive substances or are classified in tiers such no offences have been committed, substances must be returned to persons from whom they were seized unless destroyed in analysis.

Enhanced powers exist for serious offences. Constables may enter premises without warrant where reasonable grounds exist for believing offences involving Tier 1, 2, or 3 substances are being committed and one or more of the following conditions is satisfied: imminent danger to life or safety of persons on premises; evidence about to be destroyed; or delay in obtaining warrant would frustrate prevention or detection of serious crime. Constables may use such force as reasonable to effect entry. Constables entering under this power must within 24 hours report circumstances to superintendents or officers of higher rank, who must record justification for entry without warrant.

Where reasonable grounds exist for suspecting vehicles are being used for commission of offences involving Tier 1 or 2 substances, constables may stop vehicles and search them without warrant. Constables may require drivers to stop and submit to searches of vehicles and persons found within. Constables may seize any psychoactive substance or other item reasonably believed to be evidence. Senior officers of superintendent rank or above may authorise directed surveillance or use of covert human intelligence sources where necessary for preventing or detecting offences involving Tier 1 or 2 substances. Authorisation is subject to provisions of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, and all authorisations must be reported to the Investigatory Powers Commissioner.

Where reasonable grounds exist for suspecting persons have committed or are committing offences involving Tier 1, 2, or 3 substances and offences have generated proceeds, constables may apply to justices for production orders requiring financial institutions to produce documents or information relating to financial affairs. Financial institutions must comply within seven days. Failure to comply without reasonable excuse constitutes offences, and institutions are liable on summary conviction to fines.

The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 applies to all offences involving supply of psychoactive substances classified in Tier 1, 2, 3, or 4. Confiscation orders may be made against persons convicted of such offences, and courts may determine benefit obtained from criminal conduct. Where persons convicted are found to have criminal lifestyles, there is a presumption any property held was obtained through criminal conduct unless the contrary is proved. Constables or customs officers may seize cash exceeding £1,000 where reasonable grounds exist for suspecting the cash is proceeds of offences or intended for use in connection with offences. Cash may be detained initially 48 hours, which period may be extended by magistrates' courts for successive periods not exceeding three months each. Magistrates' courts may order forfeiture of cash if satisfied on the balance of probabilities the cash is proceeds of unlawful conduct or is intended for use in unlawful conduct.

The Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 applies to importation and exportation of psychoactive substances classified in Tier 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Importation or exportation in contravention constitutes offences under section 170 of that Act, and customs officers have all powers of search, seizure, and detention conferred by that Act. Goods imported or exported in contravention are liable to forfeiture.

Part 13: Ancillary Offences

Cultivating plants for purposes of unlawfully producing or supplying psychoactive substances classified in Tier 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 constitutes offences. Cultivation includes sowing, planting, tending, nurturing, or harvesting plants. It is a defence to prove cultivation was for personal consumption in circumstances not constituting offences. Conviction carries up to ten years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Manufacturing psychoactive substances classified in Tier 2, 3, 4, or 5 without licences granted under Part 7 or Part 8 constitutes offences. Manufacture includes any process by which substances are extracted, synthesised, or otherwise produced, and includes conversion of one psychoactive substance into another. Conviction carries up to fourteen years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Importing or exporting psychoactive substances classified in Tier 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 without lawful authority constitutes offences. Conviction for Tier 1 substances carries life imprisonment, fines, or both. Conviction for Tier 2, 3, or 4 substances carries fourteen years imprisonment, fines, or both. Conviction for Tier 5 substances carries seven years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Possessing chemical substances or reagents commonly used in manufacture of psychoactive substances where circumstances give rise to reasonable inference the person intends to use the chemical for unlawful manufacture constitutes offences. Circumstances giving rise to such inference include possession of multiple precursor chemicals, possession of manufacturing equipment, or absence of any legitimate industrial, educational, or scientific purpose. It is a defence to prove possession was for legitimate industrial, educational, or scientific purposes. Conviction carries up to seven years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Possessing apparatus or equipment specifically designed or adapted for use in manufacture of psychoactive substances where circumstances give rise to reasonable inference the person intends to use the apparatus or equipment for unlawful manufacture constitutes offences. It is a defence to prove possession was for legitimate industrial, educational, or scientific purposes. Conviction carries up to five years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Occupiers of premises who knowingly permit premises to be used for unlawful production of any psychoactive substance classified in Tier 1, 2, 3, or 4, unlawful supply of any such substance, or consumption of any psychoactive substance classified in Tier 1, 2, or 3 commit offences. For these purposes, persons knowingly permit use of premises if they know or ought reasonably to know premises are being so used and fail to take reasonable steps to prevent such use. Conviction carries up to fourteen years imprisonment, fines, or both.

Using, employing, or otherwise involving children under 18 in production, transport, or supply of any psychoactive substance classified in Tier 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 constitutes offences. For sentencing purposes, these offences are subject to minimum terms of imprisonment of fourteen years, from which no reduction may be made for guilty plea or other mitigating factors. Involvement of children in commission of offences constitutes aggravating factors in sentencing for those offences, in addition to separate offences. These provisions recognise exploitation of children in drug supply chains warrants particularly severe consequences.

Inciting another person to commit offences, or conspiring with another person to commit offences, attracts the same penalty as if the person had committed the substantive offence. Attempting to commit offences attracts the same penalty as if the person had committed the substantive offence.

Part 14: Revenue and Healthcare Funding

Licensing fees provide revenue streams supporting public health interventions. Apothecary licence applicants pay £25,000 non-refundable initial application fees. Annual renewal fees are determined by turnover: up to £500,000 turnover pays £10,000; £500,000 to £2 million pays £25,000; £2 million to £5 million pays £50,000; over £5 million pays £100,000. Manufacturer licences carry £100,000 annual fees. Importer licences carry £50,000 annual fees. Retail licences under Part 8 carry fees between £500 and £5,000 determined by local authorities. Research licences carry £500 annual fees paid to universities maintaining the register. All fees except research and retail licence fees are payable to His Majesty's Revenue and Customs and must be paid before licences are granted or renewed. Failure to pay fees results in immediate suspension until fees are paid.

Excise duties are charged on supply of Tier 4 substances from licensed suppliers to apothecaries at rates specified by Commissioners for His Majesty's Revenue and Customs by regulations, and on retail sale of Tier 5 substances at rates specified by Commissioners by regulations. Duty is payable by suppliers or retailers at time of supply or sale and must be accounted for to HMRC in accordance with regulations. Regulations may specify different rates for different substances or classes of substances, and may specify rates by reference to weight, volume, transaction value, or combinations thereof. In setting rates, Commissioners must have regard to objectives of discouraging excessive consumption whilst not creating incentives for illicit supply. Regulations are subject to affirmative resolution procedure.

Failure to pay duty when due constitutes offences carrying fines not exceeding level 5 on summary conviction, with further liability to pay interest on unpaid duty at rates applicable to tax debts. Evading or attempting to evade duty by fraud, deception, or any dishonest means constitutes offences carrying up to seven years imprisonment, fines, or both. HMRC may seize goods on which duty has not been paid and detain those goods until duty is paid together with any penalty and interest. Provisions of the Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 relating to recovery of duties, seizure and forfeiture of goods, and prosecution of offences apply in relation to duties imposed under this Part as they apply in relation to duties of customs and excise.

All revenue from licensing fees, excise duties, fines for offences, and sums forfeited or confiscated under the Act or Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 in relation to offences under the Act is paid into the Consolidated Fund but is ring-fenced for purposes specified in the Act and may not be applied to any other purpose. The Treasury must in each financial year make payments out of the Consolidated Fund to bodies responsible for delivering specified services in amounts required to meet expenditure allocations. This establishes the Psychoactive Substances Healthcare Fund, which is entirely hypothecated—every penny raised through this legislation flows directly into healthcare interventions addressing substance-related harm.

Mandatory expenditure allocations are: not less than 40 per cent to addiction treatment services including residential rehabilitation, community addiction teams, medication-assisted treatment, psychological therapies, peer recovery support, family support, employment and housing support, and aftercare and relapse prevention; not less than 20 per cent to harm reduction services including needle and syringe programmes, drug checking and testing services, supervised consumption facilities, outreach and engagement services, safer use education, overdose recognition and management training, wound care and infection prevention, and blood-borne infection testing and treatment; not less than 15 per cent to mental health crisis services provided by or on behalf of the NHS; not less than 10 per cent to antidote research, development, and distribution including naloxone distribution to police, fire, ambulance services, prisons, and community distribution to persons at risk; not less than 2 per cent to universities maintaining the register for funding research into toxicology, pharmacology, and epidemiology of psychoactive substances; not less than 5 per cent to public education concerning psychoactive substances, harm reduction, and addiction treatment; not less than 3 per cent to evaluation and monitoring of the Act's operation including data collection, research into public health outcomes, and preparation of reports to Parliament; and any remaining sums to the NHS for general healthcare provision.

Services funded must be evidence-based, delivered in accordance with NICE clinical guidelines or other recognised bodies of clinical expertise, available without charge to persons ordinarily resident in the United Kingdom, and in the case of harm reduction services, delivered in non-judgmental manner not requiring abstinence as condition of access. The Secretary of State must ensure naloxone and other opioid antidotes are made available without charge and without prescription to any person requesting them, supplied without charge to all emergency services and custodial institutions, and maintained in stock by apothecaries for free distribution. Grants may be made to universities, research institutions, and pharmaceutical companies for research into novel antidotes, clinical trials, and manufacturing and stockpiling.

Public education programmes must be evidence-based and must not rely upon fear-based messaging or exaggeration of risks. Education for young persons must provide accurate information and equip young persons with skills to make informed decisions and resist peer pressure. Training concerning psychoactive substances, harm reduction, and addiction treatment must be provided to healthcare professionals, teachers, youth workers, social workers, and other professionals working with persons at risk of harm.

The Secretary of State must lay before Parliament in each financial year reports concerning Fund operation, specifying total revenue received from each source, total expenditure on each category of service demonstrating compliance with minimum allocation requirements, performance indicators and outcome measures for each category including numbers accessing services, waiting times, treatment completion rates, and public health outcomes. Accounts must be audited by the Comptroller and Auditor General, and audit reports laid before Parliament together with annual reports. This creates comprehensive transparency ensuring revenue is applied to purposes Parliament specified rather than disappearing into general government spending.

Part 15: Professional Regulation