The State As Parent: How Emergency Rescue Became Permanent Custody

The British state once rescued children only when families collapsed. Today it feeds them breakfast, dictates their moral education, fines parents who disagree, and jails those who resist — all while presiding over care homes where thousands were raped, beaten, and destroyed.

For centuries, British law recognised a simple and ancient compact. The family was sovereign. The child belonged — legally, morally, practically — to its parents. The state stood outside the door unless the family ceased to exist entirely. When a mother died and a father vanished and no uncle or grandmother stepped forward, the parish intervened. It fed the orphan. It housed the abandoned. It apprenticed the destitute to a trade. This was emergency guardianship, not shared parenting. The Poor Law of 1601 enshrined this principle and, for all its harshness, the workhouse system of 1834 reinforced it: the state would catch children falling through the floor of civilisation, but it had no business rearranging the furniture in a functioning home.

Even the landmark Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act of 1889 — the so-called Children's Charter — preserved this boundary with surgical care. For the first time, the state could enter a home, arrest a parent, and remove a child. But the threshold was deliberately severe. Not imperfection. Cruelty. Not poor judgement. Demonstrable harm. The law recognised something British parliaments would later forget: parents possess authority even when they are imperfect, because imperfection is the universal condition of parenthood, and no institution — least of all the state — has ever improved upon it.

The question is not whether the state should ever have crossed the threshold. It should. Children beaten, starved, and abandoned need rescue, and the 1889 Act was a noble and necessary law. The question is what happened after the rescuing was done — when the state, having tasted authority over childhood, found it could not stop swallowing.

Feeding Somebody Else's Children

The Education (Provision of Meals) Act 1906 looks modest in the statute books. It merely empowered local authorities to provide school meals. It did not compel them. It did not remove children from homes. It attracted little of the fury reserved for later reforms. And yet it is the single most consequential philosophical shift in the history of British family law, because it established a principle from which the modern state has never retreated: if we require your child's attendance, we assume responsibility for feeding your child.

Before 1906, feeding a child was exclusively a parental function. After 1906, the state could feed children whose parents were alive, present, and functioning — not because those parents had failed, but because the state had decided it could do part of the job better. The justification was not child survival. It was national efficiency. The Boer War had revealed an alarming number of malnourished military recruits, and the state concluded it could no longer rely exclusively on parental nutrition to produce soldiers fit for imperial service. The child was reframed — subtly but unmistakably — not purely as a member of a family, but as a national asset whose physical development served the interests of the Crown.

Critics at the time saw exactly what was happening. They warned the Act would usurp traditional family responsibility. They were ignored. They were also right.

Medical Inspection, Compulsory Knowledge, and the Quiet Expansion

Once the state feeds children, inspecting them follows with the inevitability of gravity. The School Medical Inspections Act of 1907 empowered authorities to examine children's bodies — diagnosing conditions, directing treatment, monitoring development. The Fisher Act of 1918 expanded the machinery further: nursery schools, medical services, special-needs provision, extended schooling. Each measure was defensible in isolation. Each was modest in scope. Together they constituted something altogether larger: the state had positioned itself as co-manager of the biological and intellectual development of every child in the country.

And then came the wars.

The Butler Act of 1944, born from the urgency of a nation fighting for survival, transformed school meals from local charity into statutory infrastructure with enforced nutritional standards. By the 1950s, roughly half of all British children received school meals. Many received them free. The state had become, in the most literal sense, a routine food provider — not for the desperate, not for the orphaned, but for ordinary families whose only distinguishing characteristic was the possession of children.

The creation of the welfare state between 1946 and 1948 extended the same logic across every remaining domain of family life.

- The NHS assumed healthcare.

- Council housing assumed shelter.

- Child benefit assumed a portion of household income.

Each of these provisions emerged from genuine crisis — a nation battered by total war, a population displaced and traumatised. The impulse was honourable. The effect was structural and permanent. The state was no longer the last resort. It was the first provider, operating continuously alongside parents whether those parents needed it or not.

When the Law Changed Its Mind About Who Owns a Child

If 1906 was the philosophical hinge, the Children Act 1989 was the constitutional one. It established a principle so apparently reasonable, so superficially unobjectionable, it passed into law without the upheaval it deserved. The principle was this: the child's welfare is the paramount consideration.

Read quickly, this sounds like common sense. Read carefully, it contains a structural revolution. Because if the child's welfare is paramount, someone must decide what welfare means. And the Act made clear who holds the gavel: the state.

Before 1989, British law intervened when parental authority had collapsed — when abuse, abandonment, or destitution rendered the family incapable of functioning. After 1989, the state could intervene whenever it judged welfare to be suboptimal. The threshold shifted. Not from safety to danger. From catastrophic failure to professional assessment of adequacy. The parent was no longer presumed competent unless proven otherwise. The parent was presumed variable in competence and subject to evaluation.

The legal safeguards remain impressive on paper. Section 31 requires proof the child is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm attributable to inadequate parental care. The words "likely to suffer" are the hinge within the hinge — because they permit intervention based on risk assessment, not proven injury. Courts in cases like Re H (Minors) (1996) have interpreted "likely" to mean a real possibility rather than a theoretical one. The Human Rights Act 1998, via Article 8, demands any intervention be necessary and proportionate. Parents receive legal representation. Judges review evidence. The architecture of restraint exists.

But architecture without occupants is merely scenery. The real question is what the state does with these powers once it holds them — and the answer, across the last three decades, is: it uses them relentlessly.

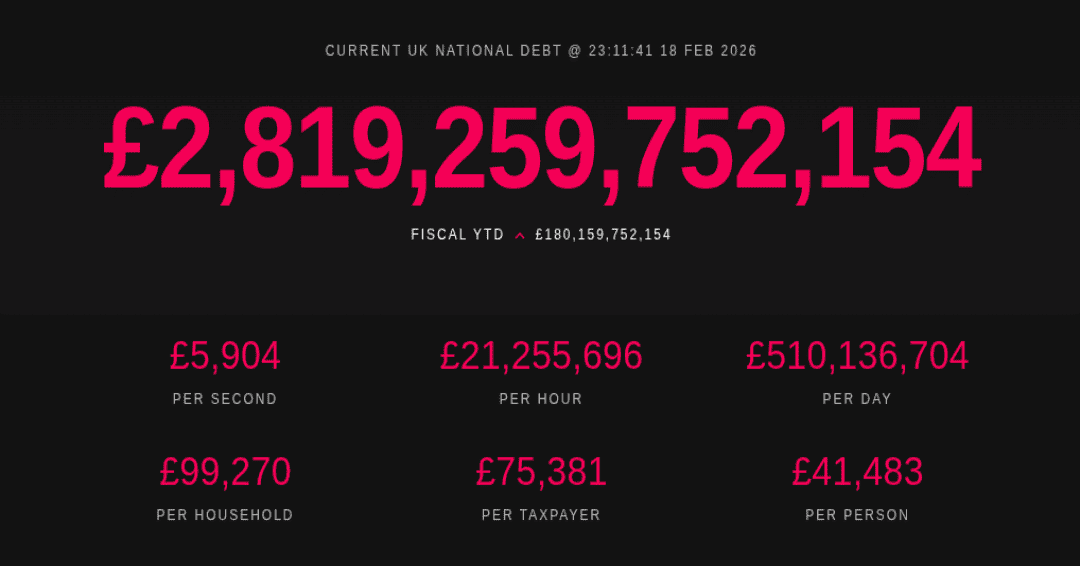

Half A Million Fines And Counting

Consider what the British state can now do to an ordinary parent — not an abuser, not a criminal, not someone who has harmed or neglected a child, but an ordinary mother or father whose child misses school.

Under Section 444 of the Education Act 1996, a parent whose registered child fails to attend school regularly commits a criminal offence. The state may issue penalty notices — fines of £80, rising to £160. If unpaid, prosecution follows. Courts may impose fines up to £2,500, community orders, or imprisonment for up to three months. The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 authorises Parenting Orders — court-mandated attendance at parenting classes, with criminal penalties for non-compliance. The Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003 introduced fixed penalty notices, removing the need for court proceedings altogether and transforming enforcement from exceptional to administrative.

These are not theoretical powers gathering dust in statute books. In the 2024/25 academic year, local authorities in England issued 492,800 penalty notices for unauthorised absence. The overwhelming majority — over ninety per cent — were for unauthorised family holidays. Not truancy. Not neglect. Holidays. Parents jailed because they took their children to the seaside in term time rather than paying the premium demanded by an industry calibrated to school schedules.

- Six parents in Derby alone served prison sentences for attendance failures. One served three separate jail terms.

- In Hampshire, a father received fifty-six days.

- In Sheffield, a mother received six weeks.

- Across England, thousands are prosecuted annually.

The Supreme Court's 2017 ruling in Isle of Wight Council v Platt confirmed even occasional unauthorised absences — in a child with an overall attendance rate above ninety per cent — can constitute a criminal offence. The message is explicit: your child's daily whereabouts are not your decision. They are the state's.

And through it all, the legal apparatus keeps growing. The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 introduced something entirely new to British law: the power to compel parents not merely to comply with attendance requirements, but to undergo behavioural correction. Parenting Orders require attendance at state-approved classes. They impose ongoing supervision. They direct future conduct. Failure to comply is a criminal offence. These are not emergency measures for abusive households. They are routine tools applied in truancy cases, anti-social behaviour proceedings, and youth offending matters. The state no longer merely punishes a parent for a discrete failure. It instructs the parent in how to parent — and imprisons them if they refuse instruction.

The Closing of the Escape Route: Homeschooling Under Siege

In law, a crucial safety valve still exists. Section 7 of the Education Act 1996 requires parents to ensure their child receives suitable education — but it does not require attendance at a state school. Parents may homeschool. They need not follow the national curriculum. They need not seek prior approval. This is the last legal fortress of parental educational sovereignty, and it is the reason the British system has not yet become a closed circuit of compulsory state formation.

It is also under direct and sustained attack.

The Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill, introduced in December 2024 and currently progressing through the House of Lords, proposes a national register of all home-educated children. Parents would be required to provide local authorities with detailed information about their educational arrangements — including the names of everyone who contributes to the child's education and the amount of time spent with each. Lord Frost warned during the Lords debate the register demands "a vast amount of very detailed data" and requires submission of information on "education providers" — defined so broadly it could encompass anyone providing any form of teaching. Lord Jackson of Peterborough described the provisions as impossible to comply with meaningfully, observing parents educate their children constantly — "when cooking a meal together, opening a bank account, or simply talking and living life together."

Local authorities would gain the power to determine whether home education is adequate. If unsatisfied, they may issue a School Attendance Order compelling registration at a named school. If a child is already subject to child protection proceedings, parents would need permission to home-educate. The bill would also assign every child — including those educated at home — a national identification number, enabling tracking across government agencies including health and social services.

Dame Rachel de Souza, then Children's Commissioner for England, welcomed the bill as legislation for children "who have been neglected or hidden." The framing is revealing. Home-educated children are characterised not as children whose parents have made a deliberate and lawful choice, but as children who have been hidden — as though the decision to educate outside state institutions is itself a form of concealment requiring investigation.

Research tells a different story.

Brendan Case and Ying Chen of Harvard's Human Flourishing Programme found home-educated children generally develop into well-adjusted and socially engaged adults. Kevin Boden of HSLDA International testified before Parliament in opposition to the bill, warning it "interferes with the natural right of parents to raise their children." The evidence, he argued, shows home education should be celebrated rather than feared. Parliament appears uninterested.

Who Decides What Your Child Must Believe?

The question of what children learn is inseparable from the question of who decides. Before 1988, the British state funded schools without centrally prescribing detailed curriculum content. The Education Reform Act of 1988 changed this permanently, establishing a national curriculum specifying what every child in every state school must study, year by year, subject by subject.

Since then, the prescriptive detail has intensified through successive reforms. The 2014 revision under venal Michael Gove introduced requirements for young children to master technical grammatical concepts — subordinate clauses, modal verbs, expanded noun phrases — which many parents discovered for the first time only when forced to homeschool during the Covid lockdowns. One parent writing in Prospect described the experience of suddenly confronting what their children actually did all day and finding an apparatus of compulsory knowledge they had never seen, never chosen, and could not influence.

“It’s a very long time in this country since we have had real discussions about what we want children to learn and to what purpose,” former adviser Debra Myhill tells me. She would like to see a rethink across the board, not just in literacy. “It used to be a strong field of research in the sixties and seventies. Since 1988, we’ve had curriculum after curriculum, but the design has been shaped by political ideology rather than discussions about what we want education to be for. It is a choice: we as a country decide what we think is important.”

Relationships and Sex Education became mandatory in all English state schools under the Children and Social Work Act 2017, with statutory guidance issued in 2019. Parents may withdraw children from certain sex education elements — but not from core relationships education and health education. The state defines what counts as minimum social and moral knowledge, and compels participation, with only partial parental veto and no meaningful mechanism for dissent.

The state has issued the right for itself to enact force on your family if you do not morally agree "relationships" involve sodomitical partners, "gay adoption," so-called "open marriage," or "alternate modes of kinship" are legitimate, or acts of conscience at all. The Crown has decided you are to accept the sacred secular religion of universalism.

Schools enforce this content not through gentle suggestion but through the hard technocratic machinery of Ofsted inspection, performance tables, and institutional consequences. A teacher quoted in Prospect put it simply: "If Ofsted asks about whether an aspect of the curriculum is being taught, you teach it."

The chain is seamless.

- Government defines content.

- Ofsted inspects compliance.

- Schools enforce it.

- Attendance laws compel participation.

- Parents who object face fines, prosecution, and imprisonment.

The only exit is homeschooling — and Parliament is working to close it.

When The State Became The Abuser

If the state's assumption of parental authority were justified by superior outcomes, the argument might hold. It is not. The documented record of state custody of children is not merely imperfect. It is catastrophic.

The Waterhouse Inquiry, published in 2000 after a three-year investigation costing £13 million, confirmed widespread sexual and physical abuse of children in council-run care homes across North Wales between 1974 and 1990. At Bryn Estyn alone, two of the most senior staff members were found to have been "habitually engaged in major sexual abuse of many of the young residents without detection." Physical violence was described as "endemic." The inquiry received evidence from 259 complainants. At least twelve young people who passed through the care system in Clwyd were dead. The children in these homes had been placed there by the state — removed from families for their supposed protection, and delivered into the hands of predators employed by the authorities responsible for their welfare.

In Lambeth, the scale was larger still. From the 1930s to the 1990s, children in council care homes — including the vast Shirley Oaks complex — suffered systematic sexual, physical, and racial abuse at the hands of approximately 120 perpetrators over six decades. Over 2.200 people have applied to Lambeth's Redress Scheme. More than £108 million has been paid in compensation — believed to be one of the largest payouts for institutional sexual abuse by any local authority in British history. Only six perpetrators have been convicted. Sandra Fearon, placed in Shirley Oaks at twelve after her father struggled following her mother's death, was repeatedly raped and became suicidal. On her first day, her "house parent" told her: "Just remember you're nothing." When she ran away and told police "a man is hurting me," no action was taken.

These children were wards of the state. The state had assumed parental responsibility — the very authority it now exercises over the education, nutrition, and moral formation of every child in the country. And in these homes, the state did not merely fail to parent. It presided over organised, industrial cruelty against the most vulnerable human beings in its custody.

The child migrant programme sent over 100,000 British children to Australia, Canada, and other Commonwealth countries between the 1940s and 1970s. Many had living parents. Some parents were actively misled. Children were separated from families, subjected to abuse and forced labour, and stripped of identity. In 2010, Prime Minister Gordon Brown formally apologised on behalf of the government.

The Cleveland scandal of 1987 saw over 120 children removed from functioning families on the basis of controversial medical diagnoses of sexual abuse later found to be unreliable. Most were returned home. The Cleveland Inquiry concluded authorities had acted precipitously and without sufficient evidence. In Williams v London Borough of Hackney (2018), the Supreme Court ruled a local authority had unlawfully pressured parents into surrendering custody under "voluntary accommodation" powers. In Northamptonshire County Council v AS (2015), the High Court found the removal of a newborn was unlawful — a "misuse of power."

This is the institution demanding the right to assess whether parents are adequate.

The Unnecessary Paradox Of Intervention

There is a profound and unresolved absurdity at the heart of modern British education enforcement. The overwhelming majority of British parents — an almost universal proportion — want their children to receive the best education possible. Britain's education system is respected internationally. Grammar schools, the meritocratic triumph of the 1944 settlement, were dismantled beginning in the 1960s not because parents demanded it, but because politicians decided selection was ideologically inconvenient. The enforcement apparatus — half a million fines per year, thousands of prosecutions, parents imprisoned — serves virtually no-one, because the number of parents sitting at home thinking "I don't want my child to have opportunities" is vanishingly small.

The system was built for edge cases: extreme poverty, child labour, transient populations, genuine neglect. It was designed to eliminate the tail of the distribution, not to govern the median. And yet it governs the median with enthusiastic vigour. A family returning from a week in Portugal faces the same statutory machinery designed to catch children being exploited in Victorian mills. The sledgehammer built for catastrophe is now deployed against inconvenience. The entire apparatus of compulsory attendance — Section 444, fixed penalty notices, Parenting Orders, Education Supervision Orders, prosecution, imprisonment — operates as though the British parent is a latent threat to their own child's future, requiring perpetual surveillance and the credible promise of punishment to fulfil a duty they were already fulfilling voluntarily.

The Line They Crossed and the Ground They Must Surrender

The trajectory is historically traceable, morally indefensible, and constitutionally dangerous. It proceeds in five stages, each masking the next.

- First: the state replaces parents only when parents are absent.

- Second: the state assists parents in crisis.

- Third: the state supplements parents routinely.

- Fourth: the state supervises parents.

- Fifth: the state operates in parallel to parents — feeding their children breakfast, defining their moral education, tracking them through national databases, fining parents who deviate, imprisoning parents who resist, and proposing legislation to eliminate the last legal route of escape.

From last resort to routine provider to supervisor to parallel system to monopoly. The threshold dropped so gradually most people never noticed. The Elizabethan parish officer who walked into a home only when the parents were dead has been replaced by an administrative apparatus issuing half a million penalty notices a year to parents whose children missed a week of geography.

And the state's own record as parent is not merely poor. It is soaked in scandal, abuse, institutional cruelty, and the broken lives of children it swore to protect. Bryn Estyn. Shirley Oaks. The child migrants shipped to the colonies. The Cleveland families torn apart on flawed diagnoses. The newborns seized unlawfully. The parents coerced into surrendering custody. The £108 million in compensation Lambeth alone has paid — not to parents whose authority it undermined, but to children it destroyed.

This is not a system deserving of expansion. It is a system requiring confrontation — by parents who will not be fined into silence, by parliamentarians who remember the state was built to serve families rather than replace them, and by a public unwilling to watch the last vestiges of parental sovereignty dissolve into the machinery of preventive governance.

The British family existed before the British state. It will exist after it. The only question is whether this generation of parents will permit the state to forget this — or whether they will remind it, forcefully, where the threshold belongs.