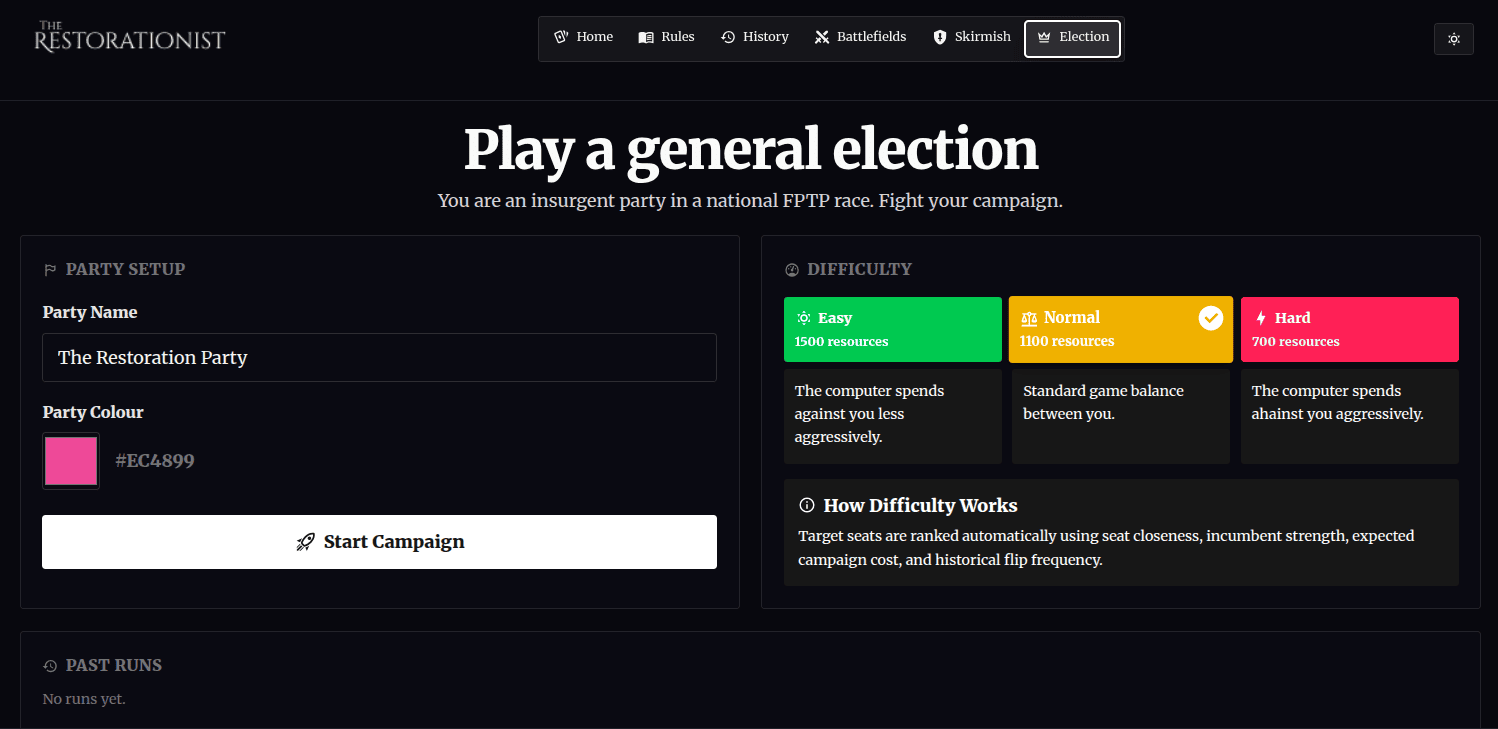

Tearing Up Magna Carta: The Hidden Judicial Staffing Emergency

As David Lammy proposes abolishing jury trials for 75% of Crown Court cases, Britain's judicial recruitment crisis reveals a justice system on the brink of constitutional collapse—but scrapping ancient rights won't solve the rot within. Magna Carta is Britain, not an optional dirty napkin.

This week, leaked government memos revealed David Lammy's proposal to eliminate jury trials for the majority of criminal cases, restricting them solely to murder, rape, manslaughter and matters of public interest. The Justice Secretary's briefing note, marked "sensitive and official", declares there is "no right" to jury trials in the UK—a statement so breathtaking in its constitutional illiteracy it deserves pride of place in any anthology of ministerial hubris.

The right to be judged by one's equals was enshrined in Magna Carta in 1215, and has been described by former attorneys general as "deeply ingrained in our national DNA". Lammy himself, writing in The Telegraph in 2020, praised jury service as ensuring "fairness and representation in the criminal justice system" and forming "part of the bedrock of our democracy".

Five years later, in office, he proposes to dismantle it.

The Crown Court backlog now approaches 80,000 cases, with victims withdrawing and trials delayed for years. But the proposal addresses symptoms whilst ignoring causes entirely. Barbara Mills KC, Chair of the Bar Council, stated the criminal justice system is not in crisis because of jury trials. The focus, she argued, should be on fixing the inefficiencies plaguing the system—inefficiencies which could be resolved now and make a real difference without constitutional upheaval. Instead, ministers have chosen the path of least resistance: abolishing rights rather than addressing the machinery.

The Machinery Is Breaking

Behind Lammy's constitutional vandalism lies a crisis so profound it threatens the judiciary's capacity to function as an independent branch of the state. The numbers paint a picture of systemic collapse.

The Crown Court backlog reached 76,957 by the end of March 2025, 11% higher than March 2024. Over 18,000 cases have been open for a year or more—a quarter of the total backlog and a new record. These are not abstractions. Each represents a victim waiting, a defendant in limbo, a witness whose memory fades with every passing month.

Adult rape survivors now wait an average of 417 days between an offender being charged and the case being completed in the Crown Court, though many wait far longer. The number of adult rape cases waiting to go to court stands at 4,086, which is 70% higher than two years ago. One survivor, Maria, was forced to wait 3 years and 7 months for her case to go to trial. After learning of yet another postponement, she attempted to take her own life.

Justice delayed is justice denied—but this understates the horror. Justice delayed is trauma compounded, evidence degraded, witnesses lost, and defendants spending months or years on remand before trial. The system's glacial pace has become its own form of punishment, meted out to guilty and innocent alike.

Where Have All the Barristers Gone?

The proximate cause of this catastrophe is simple: there are not enough people to operate the system. Last year 1 in 20 Crown Court trials was abortive because there was no barrister available to either prosecute or defend or both.

More than 1,000 duty solicitors have left since 2017—a fall of more than a quarter. The legal profession has haemorrhaged talent because criminal legal aid work is no longer financially viable. Until recent increases, there had been no increase in the rates of criminal legal aid since 1998—a quarter-century of real-terms pay cuts whilst workloads swelled and complexity increased.

Between 2018-19 and 2023-24, the number of self-employed barristers declaring their work as crime-only fell by 184, from 2,568 to 2,384, whilst employed barristers dropped by 58. These statistics, dry as they are, understate the crisis. They do not capture the burned-out practitioner who switches to commercial work, the talented graduate who never considers criminal law because the fees make it untenable, or the experienced advocate who simply cannot afford to continue.

Recent government announcements trumpet increased funding. In December 2024, criminal legal aid solicitors received an additional £92 million per year, bringing the total uplift to 24% since the Criminal Legal Aid Independent Review. This sounds substantial until one remembers it follows decades of erosion. Even with these increases, many practitioners remain sceptical the profession can be rebuilt quickly enough to address the crisis.

The Criminal Legal Aid Advisory Board's first report made clear the scale of the challenge. Substantial immediate additional funding above the 15% recommended by the review is required to meet its aims. An immediate uplift of fees for rape and serious sexual offences is required to address the shortages of advocates doing this work. Without properly remunerated barristers and solicitors, the government's missions to reduce violent crime and halve violence against women remain hollow promises.

The Bench Is Empty

If the Bar faces a crisis, the Bench faces an emergency. Judicial recruitment rounds increasingly return with shortfalls. The most recent exercise for salaried tribunals (First-tier and Employment) showed new trends of concern with significant shortfalls. For Judge of the Employment Tribunals, there was a significant decrease in number of applications since the previous exercise.

These are not isolated incidents. The recruitment picture for many judicial offices in England and Wales has changed significantly in recent years with more frequent and higher volume recruitment for most types of judges and a greater proportion of exercises resulting in shortfalls. Some posts receive zero qualified applicants. The pipeline is drying up.

The government's solution? In March 2022, the mandatory retirement age for judges was raised from 70 to 75. This addresses resource problems by retaining experienced judges for longer, but it is a sticking plaster on a haemorrhage. If the mandatory retirement age was raised to 72, about 245 judges—nearly a quarter of the current recruitment programme—would be retained each year, and 399 if it was 75. These are not new judges; they are existing judges working longer because there is nobody to replace them.

David Gauke acknowledged in 2019 there remains a problem with shortages on the bench having a knock-on effect on those picking up the extra burden. At the time, the High Court was short by 18 judges, with that shortage expected to increase. "We are not getting the number of applicants we want," he said. "There is a risk we have a vicious cycle here, because that then increases the workload which can itself make the experience of being a judge less attractive."

That vicious cycle continues. Overwork drives people away, which increases overwork for those who remain, which drives more people away. Meanwhile, the Crown Court has approximately 75,000 outstanding cases, 11% higher than one year earlier and 17% higher than where the Ministry of Justice previously predicted it would be.

The Productivity Paradox

Here is the truly damning statistic: the number of sitting days increased by 29% between 2019 and 2024, but the increase in court sitting days has not translated into a commensurate increase in case disposals, which were 17% higher in 2024 than in 2019.

The courts are sitting longer but achieving less.

Productivity in the crown court has fallen dramatically, by as much as 20% or more since 2016. Fewer hours are sat per day because more time is wasted waiting for lawyers to arrive or defendants to be delivered from prison, or on trials cancelled or rescheduled on the day. Cases are repeatedly listed for trial and then delayed because there is no time to hear them—even though fewer trials are scheduled each day.

The proportion of trials which commence as planned remained stable at 43%, below pre-COVID rates which averaged around 50%. The percentage of ineffective trials—those rescheduled—has stabilised at 25%, roughly double the pre-2020 rate of 13-19%. Every ineffective trial means victims and witnesses prepared themselves for nothing, lawyers wasted preparation time, and court resources were squandered.

The major drivers of poor productivity are not having enough criminal lawyers, badly maintained court buildings, shortages of court staff and poor technology. None of these offer quick wins, but all can be addressed with sustained investment and systemic reform. Instead, the government proposes to abolish jury trials.

Why Juries Matter

Some 55% of the public have 'a fair amount' of trust in the jury system to deliver the right verdict and 8% 'a great deal'. Compared to just 36% having a fair amount of confidence in the courts and judicial system as a whole—and 17% having no confidence at all—juries are the justice system's most trusted component. Lammy proposes eliminating them.

His proposals go far beyond Sir Brian Leveson's review recommendations. Leveson suggested creating an intermediate court in which a judge would sit with two lay magistrates for mid-range offences. Lammy wants to remove the lay element entirely. Almost 90% of defendants convicted in the crown court in the 12 months to June 2025 were given sentences of 5 years or less—meaning Lammy's proposals would strip jury trial rights from the vast majority of Crown Court defendants.

Court judges are extremely unrepresentative of society as a whole: 68% are over 50, 61% are men, and around a third went to private school. Fewer than 10% of new judicial appointments went to those from lower socio-economic backgrounds in 2024-25. Juries provide both a check on state power and represent 'the average person' in court decisions. Removing them concentrates immense power in the hands of a judiciary that looks nothing like the communities it serves.

The Law Society called the proposals extreme, stating "our society's concept of justice rests heavily on lay participation in determining a person's guilt or innocence". Senior figures in the criminal justice world have slammed the plan as 'the biggest assault on our system of liberty in 800 years', with some likening it to a Star Chamber justice system.

Riel Karmy-Jones KC, Chair of the Criminal Bar Association, said: "This is beginning to smell like a coordinated campaign against public justice". The consequences, she warned, will be to destroy a criminal justice system seen as the pride of this country for centuries, and to destroy justice as we know it.

The Constitutional Emergency

A functioning judiciary is not a luxury. It is a constitutional necessity. When recruitment rounds fail, when posts go unfilled, when experienced judges must work past 70 because there is nobody to replace them—these are not mere administrative inconveniences. They signal a branch of government losing its capacity to function.

The separation of powers rests on each branch possessing sufficient resources and independence to check the others. The Criminal Justice Board reconvened in 2024 after an absence of two years over which the backlog rose further. Two years without strategic oversight as the crisis deepened. This is governance by neglect.

Lammy's proposals would make England and Wales out of step with most democracies around the world. Other nations facing court backlogs have invested in their systems—more judges, better technology, improved court facilities. Britain proposes to abolish defendants' rights instead.

The backlog did not appear overnight. The MoJ set an ambition in the October 2021 spending review to reduce the backlog from 60,000 to 53,000 by March 2025. It now stands at nearly 77,000—a 28% increase from where they aimed to be. The MoJ was unable to confirm when the backlog might come back down to 53,000.

This is not a temporary pandemic hangover. Between 2021 and 2023, the crown court disposed of significantly fewer cases than the MoJ had projected, despite the level of receipts being consistently lower than the MoJ had forecast. The system is not just struggling to catch up; it is falling further behind whilst processing fewer cases than expected.

What Needs to Happen

The solutions are clear, if politically difficult. First, sustained investment in criminal legal aid to rebuild the profession. The Bar Council calls for an immediate 15% uplift in criminal legal aid fees for barristers, alongside establishment of an independent fee review body to guard against future crises. This must apply equally to solicitors.

Second, aggressive judicial recruitment with improved terms to attract talent. The shortage of judges cannot be solved by working existing judges harder or keeping them past retirement. New blood is essential.

Third, investment in court infrastructure, technology, and staff. Addressing productivity problems would take time because the major drivers are not having enough criminal lawyers, badly maintained court buildings, shortages of court staff and poor technology. None of these offer quick wins, but all are solvable with political will and funding.

Fourth, procedural reforms to reduce ineffective trials. Better case management, realistic listing, and consequences for repeated adjournments could improve throughput without sacrificing rights.

What must not happen is the abolition of jury trials to mask the government's failure to fund the justice system properly. The Law Society stated that with a sensible combination of funding and structural change, the government can solve the criminal courts backlog without resorting to extremes.

A Crisis of Legitimacy

Defenders of Lammy's proposals will argue efficiency demands sacrifice. They will point to the backlog, to victims waiting years, to the system's evident dysfunction. They will say difficult times require difficult choices.

This argument is a misdirection. The dysfunction exists not because jury trials are inefficient, but because the system has been deliberately starved of resources for decades whilst demand increased. Legal aid budgets were slashed. Courts were closed. Recruitment was neglected. And now, when the predictable consequences arrive, the response is not to rebuild what was destroyed but to abolish what remains.

The number of rape trials effectively heard in the Crown Court decreased by 71% between 2015 and 2023—a total of 4,684 fewer cases. Yet in that same period, the proportion of rape trials delayed at least once increased by 18%. Fewer trials, more delays—this is not a system overwhelmed by demand but one crippled by resource starvation.

Justice is not an optimisation problem. It cannot be rendered "more efficient" by removing inconvenient safeguards. The right to trial by jury exists precisely because efficiency and justice sometimes conflict, and our constitutional settlement chooses justice. When a single judge can imprison someone for five years, the state's power is immense. Juries dilute that power, forcing the state to convince twelve ordinary citizens of guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

Five years ago David Lammy defended the right to trial by jury, writing that jury service ensured "fairness and representation in the criminal justice system" and formed "part of the bedrock of our democracy". He was right then. He is wrong now.

The crisis in criminal justice is real, urgent, and solvable—but not by tearing up Magna Carta. It requires investment, reform, and political courage to rebuild what decades of neglect have destroyed. Anything less is not reform but surrender, cloaked in the language of modernisation whilst abandoning principles that predate the party system itself.

A judiciary unable to fill vacancies ceases to be an effective branch of the state. A justice system that abolishes ancient rights rather than addressing systemic failures ceases to deserve the name. Britain faces a choice: invest in justice, or lose it. There is no third option, whatever ministers may claim.