Understanding The English Mind Through Its Philosophical Canon

The English are not a theoretical people. They are a remembered people — shaped less by revolution than by accumulation, trusting experience over abstraction, continuity over rupture. To decode this species from Albion as an alien ambassador arriving in your UFO, here is where to begin.

Suppose a craft lands in a Wiltshire field sometime before dawn. The occupant is intelligent, patient, and genuinely curious. It has already visited Paris and come away with the Déclaration des droits de l'homme. It stopped in Philadelphia and picked up the US Constitution. It spent a week in Berlin and left carrying Hegel under one arm and a sense of profound unease under the other. Now it stands in wet grass beside a chalk horse carved into a hillside older than memory, and it wants to understand England.

Where do you begin?

Not with a textbook. Not with a treaty. Not with a constitution, because there isn't one — not in any form the alien would recognise. You begin with a confession: the English do not explain themselves easily, because the English do not explain themselves at all. They have never needed to. They simply are, in the way a river is — shaped by the land it crosses, moving always forward, never starting from scratch.

Every other great civilisation has, at some decisive moment, paused to write down what it believes. The French did it in 1789. The Americans did it in 1787. The Germans have done it several times, with mixed results. The English never have, because they have never trusted a single generation to speak for all the ones preceding it. To understand this instinct — and it is an instinct, not a philosophy — you must read the books the English have lived inside for a thousand years.

Foundations Laid in Blood and Compromise

Magna Carta and the Radical Insistence on Conditional Power

Begin where the English themselves begin, even if most of them have never read the document: Runnymede, 1215.

Magna Carta is not, despite what school assemblies suggest, a declaration of human rights. It is a business arrangement between armed barons and a king they did not trust. Its language is feudal, its concerns are propertied, and fully two-thirds of its clauses are obsolete. None of this matters. What matters is the psychological residue it left in the soil of English governance for eight centuries afterward.

Three assumptions embedded themselves so deeply into the English mind after 1215 they became invisible:

Power must justify itself. Rulers are bound by law. Liberty is inherited, not granted.

No English monarch after John could govern as though these principles did not exist. Some tried. Charles I lost his head for it. James II lost his throne. The pattern repeated until it no longer needed repeating, because the assumption had become atmospheric — like humidity, present in every political conversation without anyone mentioning it.

The alien, reading Magna Carta, would learn something vital about its hosts: the English distrust concentrated power, but they distrust mob rule even more. They do not dream of perfect systems. They dream of workable constraints.

Henry VIII and the First Brexit

In 1534, Henry VIII did something so audacious it still reverberates through the English psyche five centuries later: he told Rome to leave.

The proximate cause was matrimonial — Henry wanted an annulment the Pope would not grant. But the consequence was civilisational. The Act of Supremacy did not merely swap one church administration for another. It established a principle the English have never fully abandoned: no foreign jurisdiction shall govern English affairs.

Strip away the theology and what remains is a constitutional earthquake. Henry asserted national sovereignty over spiritual authority. He subordinated universal claims to local power. He told the largest, oldest, most prestigious institution in Western civilisation it had no writ on English soil — and he made it stick, not through philosophical argument but through statute, seizure, and sheer monarchical will.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries which followed was brutal, opportunistic, and transformative. A quarter of England's productive land changed hands within a generation. A new propertied class arose overnight — men whose wealth and status depended entirely on the permanence of the break with Rome. The Reformation in England was not, as in Germany, primarily a theological movement. It was a property settlement with prayers attached.

But the deeper legacy is psychological. After 1534, the English mind contained a new and permanent conviction: sovereignty is indivisible, and it resides here, not abroad. This instinct — insular, jealous of external authority, suspicious of supranational claims — echoes through the centuries with remarkable consistency. When the English refused to accept the supremacy of Brussels in 2016, it was not performing a novelty. It was performing a habit nearly five hundred years old. Henry's Brexit was the first. It was not the last.

The alien would note something else. The English did not reject Christianity. They rejected someone else's version of it. They kept the robes, the cathedrals, the liturgical calendar, and most of the theology — but placed the entire apparatus under English management. This is characteristically English: not revolution but appropriation. Not destruction but renovation under new ownership. The building stays. The landlord changes. The tenants barely notice.

The Bill of Rights and the Settlement

Skip forward nearly five centuries to 1689 and another document born from crisis. The Bill of Rights arrived after England had endured civil war, regicide, a republic nobody wanted, a restored monarchy nobody trusted, and finally the expulsion of a Catholic king who refused to read the room.

If one sentence captures English political psychology, the Bill of Rights supplies it: power must operate through law, not personality.

After the upheavals of the seventeenth century, England chose something astonishingly modern — not absolutism, not mob democracy, but constitutional constraint. Parliamentary sovereignty. Regular elections. Freedom of speech within Parliament. Prohibition of cruel punishments. The scaffold and the scaffold's threat, replaced by procedure and precedent.

Foreign readers must grasp the consequence: England stabilised early. Stability over generations produces a particular kind of citizen — less ideological, more procedural, deeply resistant to rupture. The English are not naturally revolutionary because their system rarely forced them to be. Continental insecurity breeds ideology. English security bred something else entirely: the expectation of gradual improvement, administered through institutions old enough to command loyalty and flexible enough to absorb reform.

Lawyers Who Built Without a Blueprint

Blackstone and the Art of Explaining What Grew

Sir William Blackstone's exceptional Commentaries on the Laws of England, published between 1765 and 1769, did something profoundly English: it did not invent a system. It explained the one already there.

This is the critical difference between the English legal imagination and its continental cousins. French jurists designed codes. German scholars constructed philosophical architectures of right and obligation. Blackstone walked into a forest of accumulated statute, precedent, and custom stretching back to the Anglo-Saxons and simply described the trees. His achievement was not creation but recognition. He made the common law legible to the common reader.

The alien, encountering Blackstone, would see the English psyche made visible for the first time: reverence for precedent, evolutionary reform, suspicion of rationalist redesign, a strange and productive comfort with ambiguity. The French write constitutions. The English accumulate them. Without Blackstone, the English are unintelligible.

Dicey and the Invisible Constitution Made Explicit

If Blackstone explains what grew, Albert Venn Dicey explains why it matters. His Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1885) crystallised three ideas every foreigner must grasp before attempting to understand Britain: parliamentary sovereignty, the rule of law, and constitutional conventions.

The deeper signal is subtler. Liberty survives in England not because it is declared but because it is practised. England trusts habits more than parchment. The written constitution — sacred, rigid, adjudicated by judges in robes — is a profoundly un-English idea. The English prefer their freedoms unwritten, defended by precedent, protected by the sheer weight of accumulated expectation. Ask an Englishman where his rights come from and he will not cite a document. He will say, with faint irritation, "They've always been there."

Hobbes and the Memory of Chaos Beneath the Order

Thomas Hobbes presents a puzzle. Leviathan (1651) is stark, mechanistic, fearful — none of the qualities usually described as English. Its vision of humanity in the state of nature as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" reads like continental pessimism rather than island pragmatism.

But remember when Hobbes was writing. Civil war. Regicide. The collapse of every institution the English had trusted for centuries. Hobbes answers a trauma question: what happens when order fails?

The English absorbed the warning even as they rejected his absolutism. Beneath the surface calm of English public life lies a quiet, Hobbesian horror of political breakdown — a cellular memory of the 1640s passed down through institutions rather than stories. Scratch an English moderate and you will often find this buried dread beneath. It explains the national preference for boring politics, for grey men in grey suits managing grey compromises. Excitement, in the English political imagination, is a synonym for danger.

Before Individualism Had a Name

Macfarlane's Detonation of a Comfortable Myth

Alan Macfarlane's excellent The Origins of English Individualism (1978) quietly detonates one of the most persistent assumptions in Western social theory: the belief individualism was a product of the Reformation, or the Enlightenment, or industrial capitalism.

Macfarlane, working from parish records, court rolls, and property transactions, argues something far more radical. The English were individualistic centuries before any of these forces arrived. As early as the thirteenth century, English society already exhibited features strikingly different from the continental peasant model: nuclear families rather than extended clans, geographic mobility, functioning land markets, contractual rather than arranged marriages, women holding property in their own names.

This matters enormously, because it means the English psyche was not converted to personal autonomy by modernity. It was predisposed toward it by deep social structures already ancient when the Tudors took the throne. Property rights, voluntary association, contractual thinking — these were not innovations. They were inheritances.

If any single book in this canon contains a genuine intellectual revelation for the foreign reader, it is Macfarlane's. The English did not become individualists. They were discovered to have been individualists all along.

Philosophers of Liberty and Caution

Locke and the English Lease on Authority

John Locke's profound Second Treatise of Government (1689) is not a revolutionary text, despite the American revolutionaries who adopted it as one. It is measured. Conditional. Almost bureaucratic in its insistence on the limits of power.

Locke explains why the English accept authority — but only contractually. Government exists to secure property. Legitimacy flows upward from the governed. Rebellion is justified, but only reluctantly, and only after every alternative has been exhausted. The English do not adore the state. They tolerate it, the way one tolerates a landlord who keeps the roof in good repair. The moment the roof leaks and the landlord refuses to fix it, the tenancy is up for review.

This produces a political culture deeply alien to societies built on charismatic authority or ideological devotion. The English expect competence, not inspiration. They want their government to work, not to move them.

Burke and the Patron Saint of English Caution

If Locke explains English liberty, Edmund Burke explains English caution.

Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) is the single most important articulation of the English conservative instinct — which is not, despite what modern politics suggests, an ideology at all. It is a temperament.

Burke watched the French Revolution with the horror of a man watching his neighbour demolish a load-bearing wall because it was unfashionable. His warning was simple: do not destroy what you do not fully understand. Tradition is stored intelligence. Society is a partnership across generations — between the dead, the living, and the unborn. Reform without rupture is not timidity. It is wisdom.

Most English conservatism — even unconscious, even among people who have never heard of Burke — is Burkean. The instinct to say "yes, but what will we break?" before changing anything significant is so deeply embedded in the English character it operates like a reflex.

Mill and the Danger the English Recognised Early

John Stuart Mill's legendary On Liberty (1859) identifies a danger still alive and still unresolved: the tyranny of the majority.

The English fear not only kings but moral conformity. Mill gave philosophical structure to a suspicion the English had long harboured — the sense a free society can suffocate its members not through law but through opinion, through the crushing weight of what everybody thinks.

This helps explain English tolerance, English eccentricity, English privacy, and English pluralism. "Live and let live" is basically Mill distilled into pub wisdom. The island protects the individual not only from the state but from the crowd.

Oakeshott and the Neurologist of the English Temperament

Michael Oakeshott's underrated Rationalism in Politics (1962) is possibly the most precise diagnosis of the English political mind ever committed to paper.

Where Burke is passionate, Oakeshott is clinical. He dismantles the fantasy — beloved of planners, managers, and technocrats — societies can be engineered from abstract theory. Knowledge, he argues, is often tacit. Tradition is compressed experience. Politics is navigation, not construction. You do not design a civilisation the way you design a bridge. You tend it the way you tend a garden, responding to conditions as they arise, trusting accumulated skill over imported blueprints.

If Burke is the prophet of English caution, Oakeshott is its neurologist — mapping the precise neural pathways through which the English instinct for gradualism operates. The alien, having read Oakeshott, would finally understand why the English react to five-year plans and grand visions not with enthusiasm but with a particular kind of polite, unmovable scepticism.

Novels Which Govern More Than Laws

Austen and the Invisible Constitution of Manners

Here the alien must be warned: do not skip fiction. The English novel is not entertainment. It is political theory in evening dress.

Jane Austen's legendary Pride and Prejudice (1813) reveals something no treatise captures: England is governed socially before it is governed legally. Watch the mechanisms at work — self-restraint, manners as moral technology, quiet hierarchy, the devastating power of reputation. The English fear social disgrace more than state punishment. A raised eyebrow can do more damage than a magistrate.

This produces extraordinary civic order with surprisingly light coercion. Where other nations require police, the English require only the drawing room. Foreigners mistake this for repression. It is closer to distributed governance — power exercised not from a centre but from a million small interactions, each enforcing an unwritten code nobody wrote down and everybody knows.

Eliot and the Deep Cartography of Provincial England

George Eliot's profound Middlemarch (1871) is perhaps the deepest psychological map of English provincial life ever drawn. Its themes are the themes of England itself: seriousness without drama, duty without spectacle, moral incrementalism, deep scepticism of grand reformers.

Dorothea Brooke arrives in the novel burning with ambition to improve the world. The world — which is to say, Middlemarch — is not improved. It continues. It absorbs her idealism the way wet clay absorbs a footprint: briefly marked, slowly smoothed. This is how England treats its reformers. Not with violence. With patience. With the quiet, devastating suggestion they might be taking themselves a little too seriously.

England changes slowly because English people mistrust intensity. Grand gestures make them uneasy. Duty does not.

Dickens and the Conscience Beneath the Hierarchy

Charles Dickens, working at the opposite end of the social scale, reveals a crucial English paradox: a hierarchical society with a powerful humanitarian impulse.

Bleak House (1852) is the anchor text — a novel about the Court of Chancery so devastating it contributed to actual legal reform. Dickens understood something about the English the English prefer not to discuss openly: they tolerate inequality, but they will not tolerate cruelty. The line between the two is not always clear, but when cruelty becomes visible — when the workhouse door opens, when the fog of Chancery lifts to reveal the wreckage beneath — the English conscience stirs with a force capable of moving institutions.

Reform movements in England are rarely theoretical. They are moral reactions to visible suffering. This is why English reform tends to be incremental rather than revolutionary. The system is not torn down. The worst abuses are removed, one by one, under pressure from a public whose sense of decency has been offended. The furnace is moral, not ideological.

The Empire, the Island, and The Travel

Kipling and the Psychology of the English Abroad

Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim (1901) is indispensable because it shows the English encountering the world — not as tourists, not as theorists, but as administrators, spies, and wanderers.

The traits Kipling reveals are uncomfortable but honest: curiosity without full assimilation, confidence without constant boasting, distance without indifference. The English abroad remained psychologically insular even at the height of empire. They carried their island with them the way a snail carries its shell — not from arrogance alone, but from a deep, pre-rational attachment to identity which no amount of travel could erode.

Island identity travels. It does not dissolve. The alien would find this puzzling. Peoples who cross oceans usually transform. The English, somehow, did not. They built railways in India, drained marshes in Mesopotamia, and mapped half the globe while remaining, at some irreducible core, parishioners of a small damp country who wanted nothing more than to go home for tea.

Churchill and England Narrating Itself Under Fire

Winston Churchill's endless A History of the English-Speaking Peoples and his wartime speeches serve a dual function in the canon.

The speeches — read aloud, as they must be — are England at full volume: defiance without hysteria, gravity without despair, courage without theatrical nationalism. Churchill did not create the English spirit. He articulated what was already there, the way a cathedral organ does not create the hymn but gives it a voice large enough to fill the nave.

The History is subtler. Churchill is doing something deliberately civilisational: he is narrating England as a continuity story. Not perfect. Not linear. But persistent. A people who forget their story become administratively governed rather than historically conscious. Churchill, whatever his flaws — and they were considerable — understood this with the clarity of a man who had read everything and remembered most of it.

Poets Who Mapped the Interior Country

Shakespeare and the Forging of a National Archetype

The Henry V history plays are not myth-making. They are myth-forming.

The English self-image emerges from these plays with startling clarity: reluctant heroism, understated courage, comradeship across rank, irony in victory. "Band of brothers" is not a line. It is a national archetype — the conviction, felt rather than argued, that England is at its best when it is outnumbered, outgunned, and fighting on ground it did not choose.

Shakespeare gave England its internal voice. Before him, the English had a history. After him, they had a story.

Blake and the Radical Hymn

William Blake is the most dangerous poet in the canon — dangerous because his work is revolutionary, and the English have domesticated it so completely they sing it at the Last Night of the Proms without the faintest awareness of what they are singing.

"Jerusalem" asks whether Christ walked in England and whether England might be rebuilt as a holy city. It is, beneath its hymnal surface, a howl of dissent — a demand for moral transformation expressed not through politics but through vision. The English contain a radical strain, but it expresses itself through art rather than guillotines. Even revolt, in England, is pastoral.

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold:

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Wordsworth, Keats, and the Landscape as Moral Space

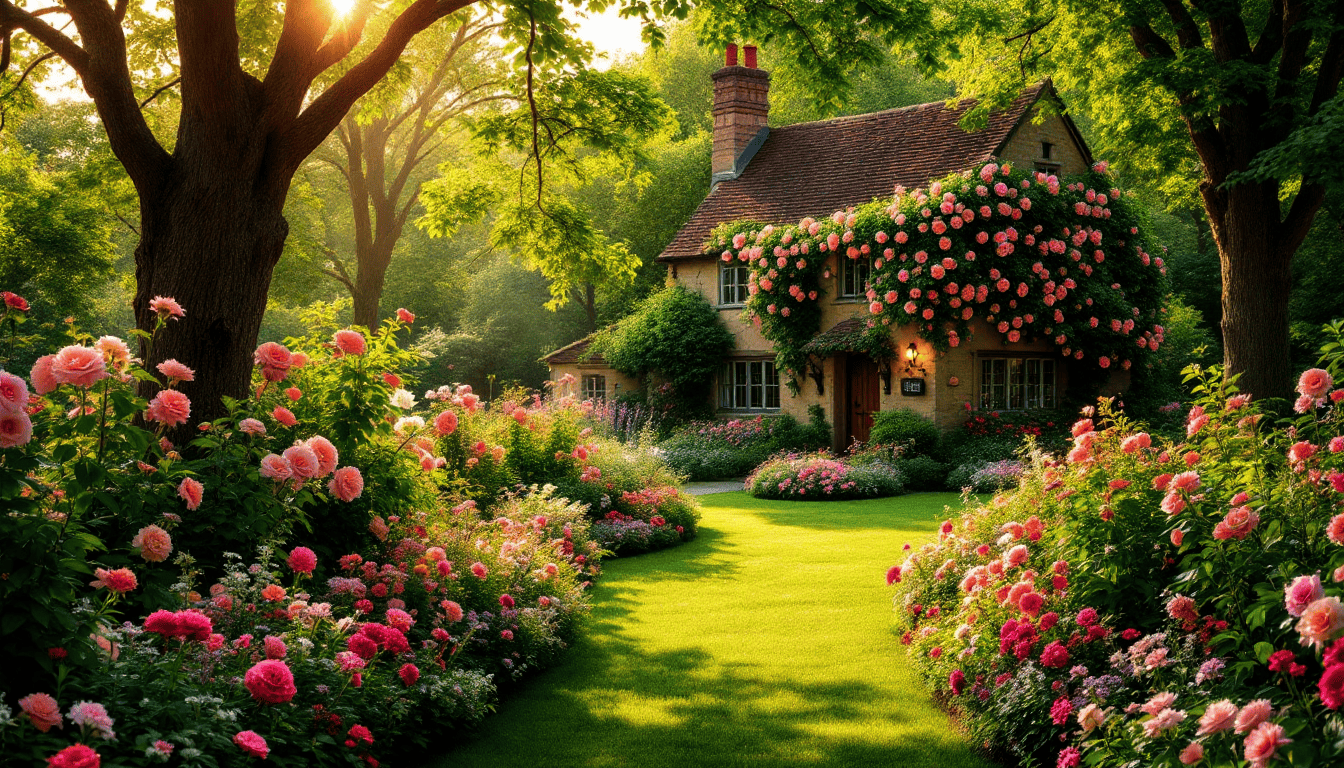

William Wordsworth's foundational The Prelude answers a question most foreigners never think to ask: why are the English so psychologically attached to landscape?

Because nature, in the English imagination, is not scenery. It is moral space. The countryside is where conscience lives. From this attachment flows the conservation instinct, the suspicion of industrial excess, the cultural ritual of walking, the stubborn refusal to allow developers near a green belt without a fight. Wordsworth interiorised the landscape, and the English have lived inside his interiorisation ever since.

John Keats deepens this further. His odes — to a nightingale, to autumn, to a Grecian urn — embed a relationship with transience into the English sensibility. Beauty matters precisely because it fades. This fosters a cultural tone which is reflective, restrained, and profoundly anti-grandiose. The English prefer poignancy to spectacle, the minor key to the major, the fading light to the blinding noon.

Tennyson, Henley, and the Stoic Backbone

Alfred, Lord Tennyson's glorious "Ulysses" captures Victorian striving at its most distilled: "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield." Empire-era England saw itself this way — forward-moving yet burdened with memory, ambitious yet aware of cost.

William Ernest Henley's bone-chilling "Invictus" strikes even deeper. Few short poems encode the English emotional stoicism posture more precisely. "I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul." Not flamboyant. Not self-pitying. Controlled defiance — the emotional signature of a maritime island which survived centuries of peril by refusing, at some molecular level, to break.

Henley was facing having his second leg amputated. As a teenager.

It's worth printing in full.

Out of the night that covers me

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance,

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate

I am the captain of my soul.

Shelley and the Proof Dissent Lives Within the Tradition

Percy Bysshe Shelley's amazing "England in 1819" earns its place because it proves something foreigners must understand: dissent is not foreign to the English tradition. It is part of it. The canon is not a hymn of self-congratulation. It contains its own critics, its own dissenters, its own furious voices. But note the crucial difference — even English radicalism is literary before it is violent. The pen arrives first. The barricade, if it comes at all, arrives last.

His wife wrote Frankenstein and his mother-in-law was the godmother of English feminism.

Sacred Soundscape and the Mythic Inheritance

The King James Bible and the Gravity of English Prose

Even secular English speech echoes the King James Bible (1611). Its cadences shaped rhetoric, conscience, metaphor, and the national instinct for moral framing. Strip away the King James Version and English prose loses its gravity — becomes lighter, quicker, more American in rhythm, less weighted with the particular solemnity the English carry into serious speech the way a cathedral carries its silence even when empty.

Tolkien, Lewis, and the Moral Imagination Beneath the Surface

J.R.R. Tolkien's infamous The Lord of the Rings encodes the emotional memory of England in mythic form. The Shire is not fantasy. It is rural England mythologised — the village green, the hedgerow, the pub, the deep suspicion of industrialised power, the conviction courage matters most when it is quiet and the hero is small. Tolkien shows something the alien must grasp: the English ideal is not domination. It is stewardship.

C.S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, articulates the moral grammar beneath the civilisation. His warning is simple: remove objective value and you do not liberate humanity. You hollow it out. Lewis bridges the gap between Christian inheritance and modern anxiety, explaining why the English historically emphasised character, duty, and moral formation over ideological commitment.

Interpreters Who Made the Architecture Visible

Orwell — The Diagnostic Eye Without Sentimentality

George Orwell's lesser-known The Lion and the Unicorn (1941) is the sharpest short anatomy of England ever written. It lists the traits with a clarity no foreign observer has matched: gentleness, law-abidingness, privacy, dislike of uniforms, hatred of bullying. Orwell saw England clearly because he loved it without romanticising it and criticised it without despising it. If Austen shows the drawing room, Orwell shows the spine.

Scruton — The Philosopher of Home

Roger Scruton's contemporary How to Be a Conservative explains attachment — the most misunderstood English trait. Home. Continuity. thout exhibition. French liberty is declarative. American liberty is evangelical. English liberty is procedural — jury trials, habeas corpus, property protections, conventions rather than codification. Freedom, in England, is less often shouted thanInheritance. The love of the ordinary. Foreign observers mistake this for nostalgia. It is not nostalgia. It is civilisational memory — the accumulated weight of a people who have lived in the same landscape for so long the landscape has become indistinguishable from identity.

Darwin — The National Cognitive Style Made Scientific

Charles Darwin's earth-shaking On the Origin of Species (1859) belongs in the canon not as biology but as epistemology. Darwin exemplifies a national cognitive style: patient observation, evidence over theory, reluctance toward grand claims, intellectual understatement. He waited twenty years before publishing. Twenty years of accumulating data, checking specimens, writing letters, doubting himself — and only then, when reality became undeniable, did he speak.

No manifesto. No intellectual theatrics. Just accumulation until the weight of evidence made silence impossible. The alien, studying English science, would recognise this temperament immediately. It is the same temperament visible in English law, English governance, and English conversation at its best: say less than you know, prove more than you claim, and never mistake confidence for competence.

What the Canon, Taken Whole, Exposes

Read together, these works do not produce a theory. They produce a portrait. And the portrait reveals something no single text can convey alone.

The English mind is not built on certainty. It is built on what the monarchy symbolises: continuity.

It does not ask, "Is this perfectly rational?" It asks, "Has this worked, and what will we break if we discard it?"

Five traits survive every upheaval — monarchy, civil war, empire, industrialisation, two world wars, and the slow acid bath of modernity. They are not trends. They are civilisational constants.

- Continuity over perfection. The English rarely seek the optimal system. They seek the survivable one. Outsiders perpetually misdiagnose England as messy. It is not messy. It is load-bearing.

- Liberty without exhibition. French liberty is declarative. American liberty is evangelical. English liberty is procedural — jury trials, habeas corpus, property protections, conventions rather than codification. Freedom, in England, is less often shouted than quietly assumed.

- Social self-regulation. England is governed socially before it is governed legally. Reputation operates as an invisible constitution. The English fear embarrassment, impropriety, and vulgarity more than punishment. This produces extraordinary civic order with surprisingly light coercion.

- Emotional containment. The stereotype is wrong. The English are not unemotional. They are anti-display. "My head is bloody, but unbowed" — not melodrama, not confession, but dignity under pressure. Island psychology tends to produce this. Survival favours composure.

- Distrust of abstraction. The English have produced great philosophers — and instinctively mistrust pure theory in political life. Society is too complex to be redesigned like a machine. When foreigners complain England lacks a grand blueprint, they are observing the feature, not the flaw.

The Furnace Beneath the Frost

Here, then, is what the alien learns. It learns the English are a people shaped less by revolution than by accumulation. It learns they trust experience over theory, continuity over rupture, restraint over display. It learns their philosophy is embedded not in treatises but in law, custom, prayer, poetry, and habit. It learns they are a remembered people — and when memory fails, identity follows.

And this is where the canon ceases to be merely interesting and becomes urgent.

Because everything these works describe is now under sustained assault — not from foreign enemies but from domestic indifference. The legal inheritance is being hollowed out by executive overreach and managerial fiat. The instinct for liberty is being smothered by a professional class which trusts process more than principle. The common law is being buried under statute. The landscape is being concreted. The language is losing its gravity. The schools have stopped teaching the canon because the canon is old, and old things make administrators nervous.

England is not being invaded. It is being forgotten — by the English.

A civilisation which no longer reads its own foundational texts is a civilisation running on fumes. The engine still turns, but the fuel is memory, and memory is finite. Burke warned of this. Oakeshott warned of this. Orwell saw it coming and wrote about it with the precision of a man filling out his own death certificate.

The canon is not a museum exhibit. It is a living inheritance — the intellectual immune system of a culture which survived a thousand years not because it was powerful but because it was coherent. Coherence is what you lose when you forget where you came from. Coherence is what no amount of management, no number of frameworks, no volume of consultation documents can replace.

So read the books. Read Magna Carta and understand why power must justify itself. Read Burke and understand why you should not demolish what you cannot rebuild. Read Austen and understand how a society governs itself without policemen. Read Orwell and see what England looks like when someone bothers to describe it honestly. Read Tolkien and remember the Shire is not a fantasy. It is a warning dressed as a fairy tale: this is what you will lose if you stop paying attention.

The English are a people who prefer the tried to the perfect, the inherited to the invented, and the durable to the dazzling.

The question is no longer whether the alien can understand them.

The question is whether the English still can.