Four Decades Of Investigations Which Never Got To The Truth

From a Westminster car park bombing to a private detective axed to death, Britain's most politically sensitive crimes share a disturbing pattern: missing files, corrupted investigations, and families denied justice whilst the state protects its own. The Establishment aggressively refuses honesty.

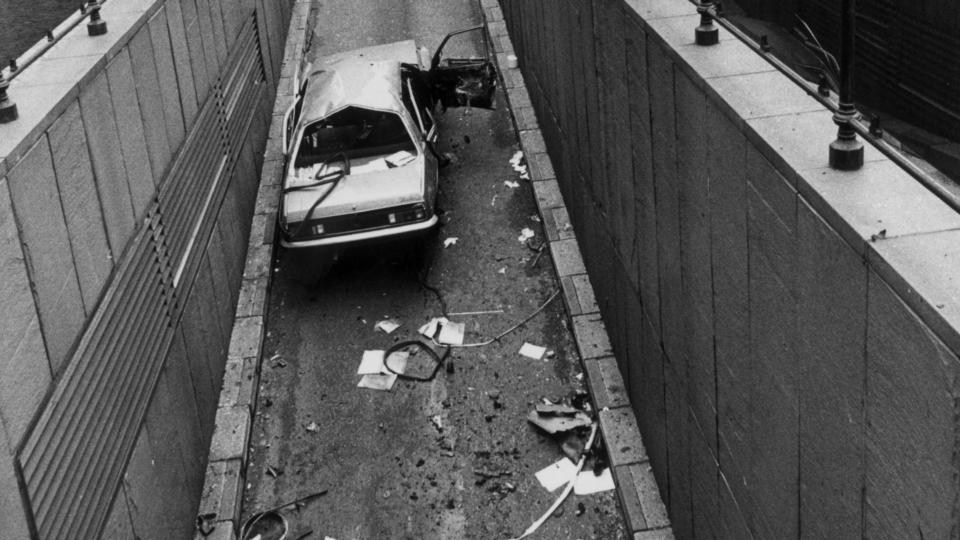

The explosion ripped through the Palace of Westminster's underground car park at precisely 2:59 pm on 30 March 1979. Airey Neave, Margaret Thatcher's closest adviser and shadow Northern Ireland Secretary, had triggered a mercury-tilt bomb planted beneath his powder-blue Vauxhall Cavalier. As emergency services cut him from the mangled wreckage, the mortally wounded MP never regained consciousness.

Within hours, the Irish National Liberation Army claimed responsibility for what it boasted was "the operation of the decade." Parliament resumed business less than an hour later—legislation, the chief whips agreed, should not be "baulked by murdering thugs."

Yet forty-five years on, fundamental questions remain unanswered. How did anyone place an explosive device inside one of the most secure buildings in Britain?

The INLA, a splinter group with roughly sixty active members in 1979, possessed neither the technical sophistication nor the security penetration such an operation would have required. Intelligence officials privately doubted they acted alone. Files concerning the assassination remain sealed well beyond their normal release date. No arrests. No prosecutions. No convictions.

Neave's death established a template—or perhaps exposed an existing one. Across four decades, Britain has systematically failed to solve some of its most politically awkward crimes. Not through incompetence alone, though there has been plenty of it. Rather, these cases reveal something more troubling: when investigations threaten powerful interests, evidence vanishes, inquiries stall, and families receive carefully managed half-truths instead of justice.

The Car Park Bomb Nobody Could Have Planted

Neave was no ordinary parliamentarian. A genuine war hero who had escaped from Colditz Castle during the Second World War, he later worked for MI9 assisting resistance fighters in occupied Europe and served on the prosecution team at Nuremberg. By 1979, he maintained close links with British intelligence services whilst serving as the architect of Conservative Northern Ireland policy. He had been preparing to overhaul UK intelligence structures and implement a radical integrationist approach abandoning devolution in Ulster.

The bomb used a sophisticated dual-switch mechanism—a timer combined with a mercury tilt-switch—designed to detonate as the vehicle angled upward on the exit ramp. Police investigations confirmed approximately one kilogram of TNT had been used.

What they could not explain was how it got there.

According to some intelligence assessments, the device had been attached whilst Neave's car was parked in the Commons car park itself—raising impossible questions about parliamentary security. Other accounts suggested it was placed outside his Westminster Gardens flat—raising equally difficult questions about how INLA operatives had tracked his movements with such precision.

Conservative MP Enoch Powell advanced a remarkable theory in 1986. He claimed Neave's assassination resulted from an Anglo-American conspiracy to secure eventual Irish unification in exchange for Ireland joining NATO. Powell argued Neave's hardline Ulster policies threatened Cold War geopolitical arrangements.

Whilst this lacked documentary evidence and reflected Powell's own political obsessions, it highlighted genuine tensions between Neave's uncompromising stance and prevailing diplomatic efforts.

Following the assassination, Thatcher—who had been preparing for a party political broadcast when she received news of Neave's murder—reportedly said: "please God, don't let it be Airey." Later she described him as "one of freedom's warriors," adding, "there's no one else who can quite fill" his rare combination of qualities. Days later, she swept to power in the general election Neave had helped engineer but would never see.

Biographer Paul Routledge met a member of the Irish Republican Socialist Party involved in the killing. The individual told him Neave:

would have been very successful at that job. He would have brought the armed struggle to its knees.

If that was the INLA's assessment, might others have shared it—including those with greater resources and different motivations?

Police files on the investigation remain closed until 2029. No explanation has been offered for this extended classification period. Military historian Patrick Bishop described the absence of any convictions as unusual given the high-profile nature of the target and security implications. The investigation into the most audacious political assassination on British soil since 1922 simply went nowhere.

The Axe, the Pub, and the Met's Corruption

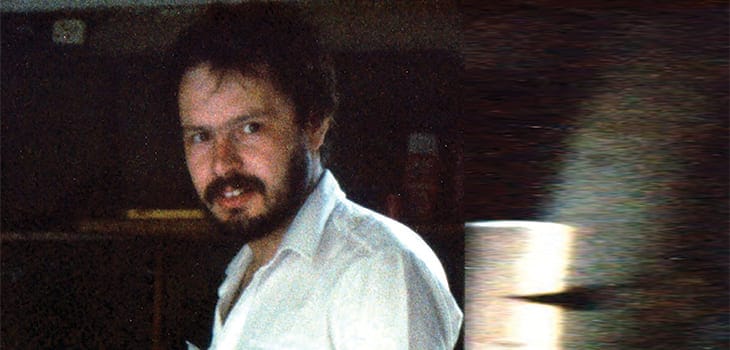

Private investigator Daniel Morgan arrived at the Golden Lion pub in Sydenham on the evening of 10 March 1987 to meet his business partner, Jonathan Rees. After drinks, Morgan walked to the car park—and into an execution.

He was found with an axe embedded in his head, his watch stolen but a large sum of money still in his jacket pocket. Notes he had been seen writing earlier were missing. The pocket of his trousers had been torn open.

What followed was not a murder investigation. It was a masterclass in institutional corruption.

Detective Sergeant Sid Fillery, based at Catford police station, was assigned to the case. He failed to disclose to his superiors one crucial detail: he had been moonlighting for Southern Investigations, the detective agency Morgan co-owned with Rees. Within weeks, six individuals including Fillery, Rees, and two other Metropolitan Police officers were arrested on suspicion of murder. All were released without charge.

Fillery subsequently retired from the Metropolitan Police on medical grounds and took over Morgan's position as Rees's partner at Southern Investigations.

At the inquest in April 1988, witnesses alleged Rees had told colleagues at Southern Investigations before Morgan's death about plans involving corrupt officers at Catford station. The suggestion was explicit: Morgan would be murdered or the murder would be arranged, and Fillery would replace him as Rees's business partner. Both men denied involvement.

Morgan's brother Alastair became the investigation's conscience. For over three decades, he pursued answers whilst detectives, journalists, and private investigators formed an increasingly visible web of corruption.

Southern Investigations evolved into what investigative journalists later described as the dark heart of Britain's illegal information trade—selling police files, financial records, and private data to Fleet Street's biggest titles, including the News of the World, Mirror Group, and Mail on Sunday.

Five separate police investigations followed. Hampshire Constabulary charged Rees and another man with murder, but prosecutors dropped the case citing insufficient evidence. Their 1989 report to the Police Complaints Authority stated "no evidence whatsoever" had been found of police involvement—a conclusion Alastair Morgan knew was false based on details they had ignored.

By the late 1990s, Southern Investigations had industrialised corruption. Rees and his team—many former police officers dismissed for misconduct—provided tabloid newspapers with illegally obtained surveillance through methods pioneering what would later be called the phone hacking scandal. The same corrupt network servicing Rupert Murdoch's newspapers was shielding Daniel Morgan's killers.

When News of the World's criminality finally exploded into public consciousness in 2011, it created a paradox. The fifth attempt to bring Morgan's killers to justice collapsed. In 2009, Rees, Fillery, the Vian brothers, and builder James Cook appeared at the Old Bailey charged with Morgan's murder; the trial collapsed in 2011 after evidence obtained from supergrasses was deemed inadmissible. By exposing the corrupt networks, the phone hacking scandal had made prosecution impossible.

An independent panel review published in 2021 found the Metropolitan Police had "a form of institutional corruption" which concealed or denied failings in the case. Between 1987 and 2011, sixty-seven people had been arrested, eight of whom were serving or former police officers.

None were convicted.

The panel concluded Scotland Yard owed the public and Morgan's family an apology for "not confronting its systemic failures."

In July 2023, the Met admitted liability and agreed an unprecedented £2 million settlement with the Morgan family. Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley acknowledged they had been "repeatedly and inexcusably let down" by a force prioritising reputation above accountability.

Daniel Morgan's murder remains unsolved—the most investigated, and most corrupted, case in British criminal history.

Files That Vanished Like Ghosts

Geoffrey Dickens, Conservative MP for Littleborough and Saddleworth, had spent years pursuing allegations of child sexual abuse involving prominent figures. In 1984, he handed Home Secretary Leon Brittan a forty-page dossier described as having the potential to "blow the lid off" the lives of notable abusers.

The dossier included details on eight prominent figures and reportedly contained the name of a former Conservative MP found with child pornography videos, against whom no arrests or charges were brought.

Suspects included:

- Leon Brittan (who received it)

- Cyril Smith

- Sir Peter Hayman

- Lord Greville Janner

- Sir Peter Morrison

- Enoch Powell

- Victor Montagu

- Roddam Twiss

- Jeremy Thorpe

- Edward Heath

- Peter Righton

- Lord John Henniker-Major

- Charles Napier

Dickens told his son Barry the dossier was "explosive." He had asked Brittan to investigate the diplomatic and civil services, even Buckingham Palace, over child sexual abuse claims. A second copy went to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

Barry Dickens later recounted an unsettling detail: his father's London flat and constituency home were ransacked the same week he handed over the dossier. Nothing was taken. "They weren't burglaries," Barry explained. "They were break-ins for a reason. We can only presume they were after something that dad had they wanted."

When Labour MP Tom Watson requested Dickens's dossier in February 2013, a Home Office review discovered it had "not been retained." The department identified 114 documents concerning child abuse allegations from 1979 to 1999 as missing, "presumed destroyed, missing or not found."

Lord Tebbit, who served in senior ministerial posts under Thatcher, later said there "may well" have been a political cover-up, noting the instinct at the time was to protect "the system" and not delve too deeply into uncomfortable allegations.

In 2013, the Home Office claimed "credible" portions containing "realistic potential" for investigation had been passed to prosecutors and police before destruction. A letter from Brittan to Dickens supposedly confirmed allegations had been acted upon. Yet civil servants gave contradictory accounts. No systematic record existed of what became of the files, who handled them, or why they were destroyed rather than archived.

In 2014, it was reported the list may be in a library at Oxford:

A secret file which is said to contain the names of paedophiles with links to the British establishment and which is rumoured to be locked away in archives at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, could be made public as part of the Government’s child abuse inquiry.

Labour MP Simon Danczuk, investigating abuse allegations against former MP Cyril Smith, reported being warned by a Conservative minister before a Home Affairs Select Committee appearance not to challenge Brittan over his knowledge of Westminster paedophile rings. The minister allegedly blocked Danczuk's path, urged him to "think very carefully" about what he would say, and warned the matter had been "put to bed a long time ago." The minister suggested Danczuk could be responsible for Brittan's death.

Danczuk was then suspended for sexting a teenager.

The star published its editor had been visited by the police with a D-notice. The BBC reported in 2015 its contents were far more widespread:

The Labour MP John Mann, who recently obtained the file, has criticised the government for failing to find it despite a Home Office review last year. He has also asked why the contents of the file were not investigated at the time.

The document seen by the BBC contains 21 names. A handwritten note in pencil suggests it was "given to Geoff Dickens, in Lobby, Jan 84". The author, a Conservative party member in the 1980s, says the information was gathered from two former Tory MPs - Sir Victor Raikes and Anthony Courtney.

When the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse finally commenced, it could not access all relevant documents. Key witnesses had died. Others refused to testify. The official file-retention policies meant materials should have been preserved, yet they had vanished as thoroughly as if they had never existed. What began as explosive allegations ended in bureaucratic fog.

The government absolved themselves of any wrongdoing.

The Chef Who Walked Into Silence

Claudia Lawrence finished her shift at the University of York's Goodricke College at 2:31 pm on 18 March 2009. CCTV captured her walking the three miles home to Heworth—her car was in the garage. A colleague gave her a lift partway.

She was last seen posting a letter outside shops near her house and was confirmed sighted at 3:05 pm. That evening she telephoned both parents and texted a friend. At 9:12 pm she received a text from a friend in Cyprus, though it remains unknown whether she read it.

Claudia never reported for her 6 am shift the following morning. When her father reported her missing on 20 March, North Yorkshire Police launched what would become their largest and most complex missing person inquiry. Despite hundreds of officers, national experts, and comprehensive searches, no trace of the thirty-five-year-old chef has ever been found.

The investigation failed spectacularly from the start.

Detective Superintendent Dai Malyn, who led a comprehensive review beginning in 2013, concluded the investigation had been:

ultimately compromised by the reluctance of some, and refusal of others, to co-operate with police enquiries.

Evidence from Lawrence's workplace at the university was not properly preserved. Police ignored credible suspects early on. When the Major Crime Unit conducted new forensic searches at her home in 2014 using "advanced techniques not available in 2009," they found additional fingerprints and DNA from individuals who had never come forward.

The investigation centred on The Nag's Head pub, steps from Lawrence's home, where she was a regular. Lawrence had relationships with several men she met whilst drinking at the pub, and her father admitted the liaisons had created "awkward situations" with lovers' partners. Nine individuals were arrested over the years, five with links to the pub. All were released without charge.

In 2015, police released CCTV footage of an unidentified man walking near the alleyway behind Lawrence's house at 7:15 pm on 18 March and again at 5:07 am and 5:50 am on 19 March. The man has never been identified.

On 8 March 2016, the Crown Prosecution Service refused to pursue a case against four men arrested on suspicion of murder, citing lack of evidence; all had been regular customers of The Nag's Head.

North Yorkshire Police complained publicly about witness non-cooperation. What they did not explain were the procedural irregularities, the delayed forensic work, and why certain investigative lines appeared abandoned.

In August and September 2021, police conducted extensive searches at Sand Hutton Gravel Pits, eight miles north-east of York, reportedly based on new intelligence they refused to specify. Nothing was found.

The lack of data, CCTV, and other evidence from the time frustrated review team efforts nearly seven years after Lawrence's disappearance. The investigation has been in "reactive phase" since 2017, though police insist it remains open. Detective Chief Inspector Sygrove stated in March 2025 that "the barrier to unlocking answers are the people who know or may suspect what happened."

Claudia's father Peter, who died in 2021 after years campaigning for answers, succeeded in getting "Claudia's Law" passed—legislation allowing families to manage missing persons' affairs after ninety days. It provided one less burden for families at their "emotional lowest ebb," he said. But answers about his daughter's fate remained as elusive as the morning she vanished.

A number of community threads on Reddit have been published which speculative heavily on a specific set of neighbours. They cite an extremely detailed article on Medium, and despite the lack of evidence claim local police and local people are certain the perpetrator was ex-boyfriend Peter Ruane.

The Billion-Pound Case Nobody Wanted to Win

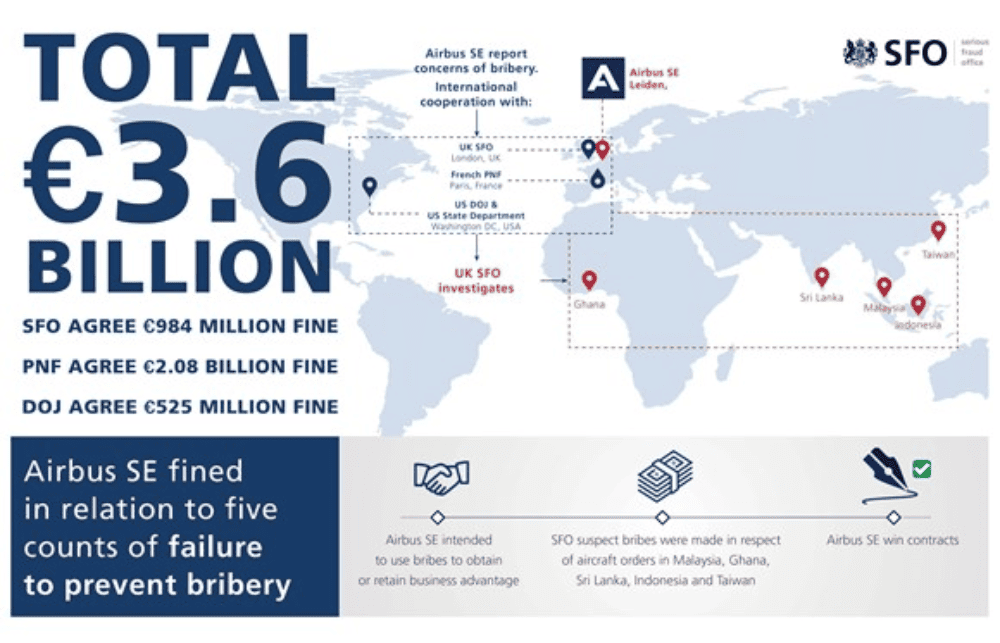

Between 2011 and 2015, aerospace manufacturer Airbus orchestrated what prosecutors described as "a pervasive and pernicious bribery scheme" spanning continents. Using a network of third-party intermediaries, the company paid bribes to government officials and airline executives across Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Taiwan, Ghana, China, Latin America, the Middle East, and Russia.

The Serious Fraud Office investigation revealed systematic corruption: hiring the wife of a Sri Lankan Airlines executive whilst misleading export credit agencies about her identity, sponsoring sports teams owned by AirAsia executives during aircraft negotiations, and disguising payments to relatives of Ghanaian officials.

By 2020, authorities in three countries had assembled devastating evidence.

Airbus had maintained a headquarters unit managing roughly 250 intermediaries and hundreds of millions of euros in suspicious payments annually. Internal reviews commenced in 2014 when UK Export Finance requested additional due diligence information.

Two years later, Airbus self-reported to the SFO.

On 31 January 2020, Airbus agreed to pay penalties totalling €3.598 billion plus interest and costs to French, UK, and US authorities: €2.083 billion to France's Parquet National Financier, €984 million to the SFO, and €526 million to the US Department of Justice.

It remains the largest global foreign bribery resolution in history.

Dame Victoria Sharp, approving the UK's Deferred Prosecution Agreement at the Royal Courts of Justice, acknowledged "the seriousness of the criminality in this case hardly needs to be spelled out. As is acknowledged on all sides, it was grave." The SFO suspended prosecution for three years. If Airbus complied with terms during that period, prosecution would be discontinued permanently.

The settlement sum exceeded all previous UK corporate penalties combined. Yet no individuals were prosecuted in Britain. Not the executives who orchestrated payments. Not the intermediaries who distributed bribes. Not the officials who accepted them.

The company paid billions; the people responsible walked away.

French and US prosecutors stated explicitly the settlement covered Airbus as a corporate entity only—individuals remained open to prosecution. The SFO, however, chose a different path. Following the near-£500 million Rolls-Royce settlement in 2017, where the SFO declined to pursue executives despite evidence of bribery across Africa, Asia, and Russia, a pattern had emerged: companies could buy their way out whilst individuals escaped accountability.

Transparency International UK noted:

Record-breaking settlements totalling billions of pounds are likely to grab headlines, but behind the numbers there are real people caught up in bribery and corruption cases. Endemic corruption in some of the world's poorest countries costs lives and ruins many more.

The judge's reasoning revealed why individuals escaped. Airbus of 2020 was "no longer the same organisation" that had orchestrated worldwide bribery. Management had changed. Board directors were different. None of the new executive committee was implicated.

Since 2015, Airbus had parted ways with sixty-three top and senior management employees. The company had cooperated fully, implemented compliance reforms, and submitted to monitoring.

International observers expressed bafflement at British leniency. The settlement closed the case whilst sealing evidence. Diplomatic implications involving France and Germany—Airbus's home governments and major defence partners—appeared to have carried more weight than criminal accountability.

Britain had obtained record financial penalties whilst ensuring the prosecution would never reveal what senior executives knew, when they knew it, or how deeply corruption had penetrated European aerospace.

The SFO stated it was "considering possible individual prosecutions." Years later, none have materialised.

The Pattern Behind the Failures

Forty-five years separate Airey Neave's assassination from current investigations into Claudia Lawrence's disappearance. Yet the cases share unmistakable characteristics.

Political awkwardness determines outcomes

Neave's murder threatened to expose intelligence failures or worse. The Morgan case implicated serving police officers in organised crime and later revealed Fleet Street's systematic criminality. Westminster abuse files endangered the reputations of prominent individuals. Lawrence's disappearance raised uncomfortable questions about investigative competence. Airbus bribery threatened diplomatic relations with France and Germany.

Evidence disappears or becomes inadmissible

Neave files remain sealed decades past normal release. Morgan case materials were destroyed across five investigations. Dickens's dossier and 114 related documents vanished entirely. Lawrence case evidence was not preserved or collected properly. Airbus evidence was sealed through settlement.

Investigations are compromised from within

The detective investigating Morgan's murder became a suspect and later joined the victim's business. Officers who should have been witnesses or suspects in Westminster abuse cases gave contradictory accounts or remained silent. Lawrence investigation failures were described as stemming from witness non-cooperation, obscuring procedural shortcomings. SFO prosecutors obtained record financial penalties whilst pursuing no individuals.

Families receive managed truths

The Neave family has never learned how security failed so catastrophically. Alastair Morgan spent thirty-four years pursuing answers before the Met admitted institutional corruption. Families submitting abuse allegations to the Home Office discovered their evidence had been destroyed. Claudia Lawrence's mother continues seeking information police claim they cannot provide. Airbus settlements closed cases whilst concealing who knew what and when.

Accountability remains theoretical

No one has been convicted in any of these cases. The INLA claimed responsibility for Neave's death, but nobody faced trial. Sixty-seven arrests in the Morgan case produced no convictions. No prosecutions emerged from Westminster abuse allegations. Nine arrests in the Lawrence case led nowhere. Airbus paid billions; individuals paid nothing.

Justice Deferred, Justice Denied

British authorities maintain these cases remain open. Files are under review. New evidence is being assessed. Investigations continue. Yet the reality is starker: when cases become politically inconvenient, British justice develops institutional blindness.

The Met's admission of "institutional corruption" in the Morgan case was remarkable not for its candour but for what it revealed about structural imperatives. When protecting reputation conflicted with pursuing truth, reputation won. When prosecuting individuals risked exposing systemic failures, prosecutions stalled. When solving crimes threatened powerful interests, crimes went unsolved.

Lord Tebbit's observation about Westminster abuse allegations applies more broadly: the instinct was to protect "the system" rather than pursue uncomfortable truths. That instinct persists. It operates not through conspiracy—though conspiracies have occurred—but through institutional self-preservation. Files go missing because preserving them creates liability. Investigations fail because succeeding would require admitting previous failures. Prosecutions stall because convictions would confirm what everyone suspects.

Forty years of unresolved cases have taught British institutions a lesson: time solves problems law cannot. Witnesses die. Memories fade. Public attention moves on. Eventually cases become historical curiosities rather than active scandals. The Neave assassination is now studied by historians rather than investigators. Morgan's murder is a cautionary tale about media corruption rather than an active homicide. Westminster abuse allegations have been subsumed into broader inquiries producing little accountability. Lawrence's disappearance approaches legacy status. Airbus has implemented compliance reforms and moved forward.

Yet the families remain. Alastair Morgan continued his brother's fight until finally securing admission of institutional corruption. Peter Lawrence campaigned until his death without learning his daughter's fate. Barry Dickens still wants to know why his father's explosive dossier disappeared. These individual tragedies illuminate systemic failure.

The comforting fiction of British justice—impartial, thorough, determined—cannot survive contact with these cases. When stakes are sufficiently high, different rules apply. Not formal rules, but practical ones shaped by institutional preservation, political sensitivity, and pragmatic calculation. Some cases can be solved. Others cannot, or must not, depending on what solving them would reveal.

This creates a parallel system where power determines outcome. Not always. Not in every case. But sufficiently often, in sufficiently important cases, to reveal the pattern.

Murders remain unsolved because solving them would expose police corruption. Files disappear because preserving them would create accountability. Investigations fail because succeeding would require admitting systemic compromise. Prosecutions stall because convictions would confirm institutional failure.

Four decades. Five cases. Hundreds of investigators. Thousands of witnesses. Billions in settlements. Zero convictions.

The pattern speaks for itself—British justice has its limits, carefully maintained and quietly enforced. Some truths, it appears, remain too inconvenient to find.