You Don't Have The Right To Break Our Lineage

Parliament governs a nation it did not create. It inherited jurisdiction over a continuity it did not author. Trustees preserve — they do not claim ownership. So by what title does the British state presume authority to break the lineage of its own people with multiculturalism and mass immigration?

The venerable Albert Venn Dicey, whose Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution remains the standard exposition of parliamentary sovereignty, stated the doctrine plainly: "Parliament has the right to make or unmake any law whatever." This is a legal description. It tells us what Parliament can do. It says nothing about what Parliament should do, and even less about what it possesses moral title to do.

Dicey himself understood the distinction. He simultaneously recognised constitutional morality — the unwritten restraints without which legal sovereignty becomes mere tyranny wearing a wig. A trustee may legally possess the keys to the vault. He may have the combination to the safe. He may, in the strictest procedural sense, be authorised to open every door and handle every asset within. But if he empties the vault and distributes its contents to strangers on the grounds it will improve the neighbourhood's economic output, he has not exercised his authority. He has abused it. The legal power existed. The moral title did not.

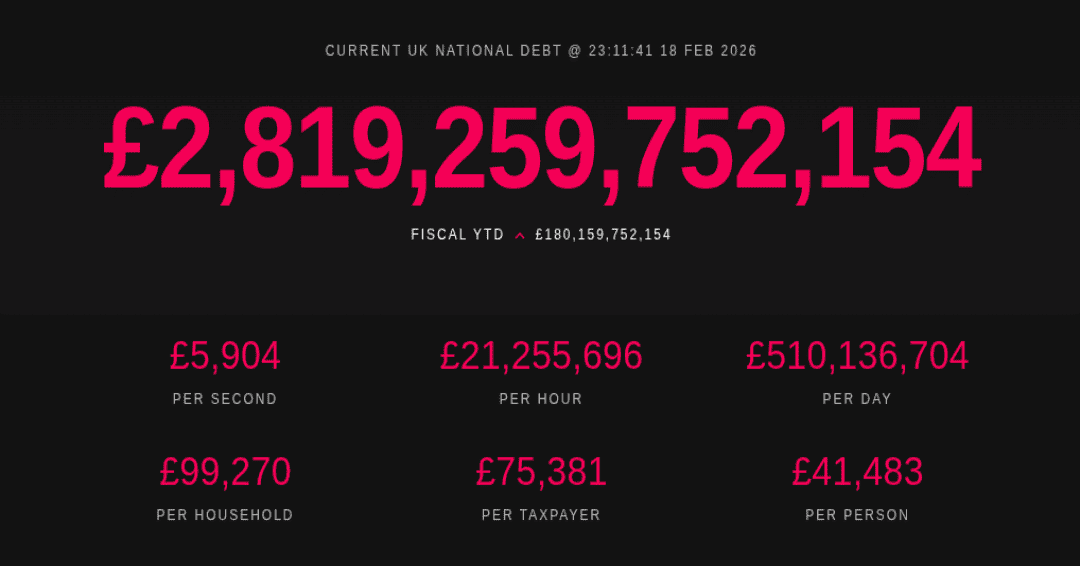

Net migration to the United Kingdom for the year to June 2023 reached 906,000 — a figure four times higher than pre-Brexit levels and one so staggering that even a sitting Prime Minister, Sir Keir Starmer, was moved to describe it not as accident but as design. "Policies were formed deliberately to liberalise immigration," he said from Downing Street. "Brexit was used for that purpose — to turn Britain into a one nation experiment in open borders."

Read those words carefully. A British Prime Minister, standing in the seat of executive power, publicly acknowledging previous governments deliberately designed policies to alter the demographic composition of the country. Not as a side-effect. Not as an unintended consequence. By design.

The vault was not burgled. It was emptied by the trustee.

The Oldest Constitutional Question in England

There is a question older than Parliament, older than Magna Carta, older even than the common law courts. It is the question every Englishman has asked, in one form or another, whenever power overreaches:

By what right?

By what right did King John tax without consent? By what right did Charles I dissolve Parliament and rule alone? By what right did James II attempt to suspend the laws of the land?

In every case, the English answer was the same. Not revolution. Not ideology. Not abstract theory imported from the continent. The answer was simpler and more devastating: You do not own what you govern. You hold it in trust. And you have broken the terms.

This is the question the British political class must now answer — not about taxation, not about civil liberties in the ordinary sense, but about something far more fundamental. By what right does the state presume to deliberately alter the long-term composition of the people from whom it derives its own authority? By what title does a temporary occupant of office claim jurisdiction over the generational continuity of an entire civilisation?

The English constitutional tradition has a word for someone who acts beyond their warrant. The word is usurper.

Burke's Partnership and the Silent Stakeholders

Edmund Burke's most important constitutional insight was not a policy recommendation. It was an observation about the nature of political authority itself. Writing in 1790, in Reflections on the Revolution in France, Burke described society as:

a partnership not only of the living, but of the dead, and the unborn.

This is not poetry. It is a constitutional principle, and it carries legal weight precisely because it describes something the English already practised — the transmission of institutions, customs, law, and life itself from one generation to the next, with each generation acting as temporary steward rather than permanent proprietor.

Burke identified three classes of constitutional stakeholder:

- the dead, who built the institutions and transmitted them;

- the living, who inherit and administer them; and

- the unborn, who possess an equitable claim to receive them intact.

The state does not sit above this arrangement. It sits within it. Parliament is not the landlord of the nation. It is the property manager — and a property manager who sells the building out from under the residents has committed a breach of fiduciary duty so profound it would, in any court of equity, result in removal.

When Andrew Neather, speechwriter and adviser to Tony Blair's government, wrote in 2009 of coming away from internal policy discussions with "the clear sense that the policy was intended — even if this wasn't its main purpose — to rub the Right's nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date," he was not describing immigration policy. He was describing a deliberate act of political interference in the composition of the constitutional community itself — an act carried out by temporary officeholders who possessed, at best, a twenty-year lease on power, and who presumed upon it as though they held the freehold.

Burke would have recognised the type immediately. He spent his career warning against precisely this species of political arrogance — the conviction of the present generation it possesses unlimited authority to reshape what it merely inherited.

A Nation Is Not Manufactured — It Unfolds

The British constitution was never constructed in a single act. It emerged gradually, through inheritance, adaptation, and the slow accumulation of custom across centuries. Burke described this process not as invention but as organic growth — the political system placed "in a just correspondence and symmetry with the order of the world."

This principle applies not only to institutions but to the people themselves. A nation is not a manufactured object. It is not an economic zone with a flag. It is a living continuity of families, loyalties, memories, habits, and inherited dispositions, unfolding across time through the accumulated choices of millions of individuals. No authority designed the English people. No committee created them. No government authored their existence. England emerged historically, across centuries, through families who settled land, tended it, married within their communities, bore children, buried their dead, and carried their particular way of being forward through the generations.

This is lineage.

And lineage is not race — a distinction so important it must be stated with absolute clarity, because the political class has spent decades deliberately conflating the two in order to make the constitutional argument unspeakable.

Lineage is time. It is the continuity of families across generations. It is grandparents and great-grandparents. Calculate any family tree in England before 1960 and the lineage is unmistakable — not because of melanin levels or skull measurements or any of the pseudoscientific rubbish the twentieth century produced, but because of the simple, observable fact of temporal continuity. The same is true in China, in Botswana, in Korea, in Venezuela. If Koreans had settled England in 1300 and formed an unbroken chain of generational transmission, their descendants would constitute English lineage today. The continuity overrides phenotype, language, and political ideology. It is defined by time and inheritance, not biology.

Every culture on earth recognises this. The Romans tended ancestral tombs along their roads. Japanese families maintain graves across generations. American military cemeteries in Europe are treated as sovereign ground — sacred, inviolable, permanent. These places represent continuity transcending the lifespan of any individual. They remind the living they are temporary participants in something older than themselves.

The state did not create this continuity. It inherited jurisdiction over it. And inherited jurisdiction is not ownership. It never was.

This is the basic principle the contemporary social media "ethno-nationalists" simply do not understand. It has nothing to do with ethnos – which is a transparent proxy for race – and all about family tree. The "ethno-nationalist" Twitter trend stupidity is explainable quite easily: it's the 10% of our population who are the remnants of the British National Party; don't like being called "racist," and resent the Left for beating them at politics.

It's also why "race science" is such snake oil. Race is an absurd concept not because it's a "social construct," but because it's so biologically nebulous despite describing a fixed classification. What race is the child of a Jamaican father and a red-hair Scottish mother? Are you the "English race" as the product of the Land of the Angles, the Normans, the Celts, and the Vikings?

"Ethno-nationalism" means race. It obviously means race. The "ethnonationalists" are simply appropriating the Left's linguistic sleight of hand to turn race into "ethnicity," and re-defining euphemistic neologisms to mean the same things they've always meant underneath. The Left are contemptuous for a lot of reasons, but they are not wrong in their diagnosis. "Ethnicity" always translates to "white race," and their idiot spokespeople are blatant neo-Nazis with hair.

The Right with their talk of race and ethnos, are idiots. The Left, and their talk of "scientific racism," "social constructs," and "isms," are fools. It is the same universal, endogenous tribalism expressed in the same tedious way.

Eight Centuries of English Thinking About Why Continuity Matters

English thought has been preoccupied with continuity across time for eight centuries — longer, perhaps, than any other philosophical tradition on earth. Unlike useless continental philosophy, which tends to begin from abstract first principles and reason downward, English philosophy begins from what already exists and asks why it deserves to persist. The result is an intellectual tradition uniquely suited to the argument at hand, because it treats continuity not as a preference but as the foundation of legitimacy itself.

Kenneth Matthews wrote in his 1943 book, British Philosophers:

The native characteristics of British philosophy are these: common sense, dislike of complication, a strong preference for the concrete over the abstract and a certain awkward honesty of method in which an occasional pearl of poetry is embedded.

Sir Henry de Bracton, writing in the thirteenth century, established the principle upon which the entire common law tradition rests: custom is the best interpreter of laws. Custom was not opinion. It was continuity made normative. The law did not descend from heaven. It emerged from the accumulated practice of generations.

Sir Edward Coke, in the seventeenth century, built upon Bracton's foundation with one of the most profound constitutional insights in English history. The law, Coke argued, embodies not individual reason but accumulated reason across generations. No single mind — not the King's, not Parliament's, not any minister's — could claim superior authority to the distilled wisdom of centuries. When Coke told King James I to his face, in Prohibitions del Roy, even the sovereign must submit to the law, he was articulating the principle all English authority exists under continuity, not above it.

John Locke made inheritance central to his theory of political legitimacy. "The power of perpetuating their property in their families," he wrote in the Second Treatise, "is the foundation of inheritance." Property here is not merely economic. It encompasses everything transmitted across generations — including the continuity of the political community itself. The state exists to protect inheritance. Not to override it.

William Blackstone codified the doctrine in his Commentaries on the Laws of England: "The law of inheritance maintains the permanent stability of society." Inheritance — the transmission of substance, memory, and legal continuity from one generation to the next — is not a conservative preference. It is the mechanism by which civilisation persists.

Burke drew all of this together into a single governing principle. The nation is an inheritance, not an asset. Inheritance imposes duties. Assets confer ownership. The British constitutional tradition treats the nation as the former. The political class increasingly treats it as the latter. And this inversion is the root of the crisis.

Michael Oakeshott, in the twentieth century, rejected the idea society is a project to be designed. It is an inheritance to be received.

Roger Scruton returned explicitly to the language of home and belonging: "Home is the place where you are known, and where others are known to you." Belonging arises from continuity. Not from administrative designation. Not from a stamp in a passport. This tradition is imprinted today in the laws of British Overseas Territories, but not at home.

This is not a niche philosophical tradition. It is the intellectual backbone of English civilisation itself — eight centuries of thinkers arriving, independently, at the same conclusion: legitimacy arises from continuity across time, and authority exists to preserve it.

Our ideas are better. We do not need to apologise for them. We do not need to explain why they are better, or that they are better. They are.

Gravestones Do Not Submit Accounts to the Treasury

Lineage is not an abstraction debated in seminar rooms. It exists in concrete form — in gravestones in parish churchyards, names in land registries, baptism records, family homes passed through generations, photographs and letters transmitted across time. These are not symbols. They are evidence of continuity. They mark the passage of real human beings across centuries in specific places. They establish the present population did not appear arbitrarily. It emerged through an unbroken chain of inheritance.

The modern state necessarily operates through abstraction. It counts populations. It measures labour supply. It manages administrative categories. These abstractions are useful for governance. But they are not the reality of human continuity. A nation is not a spreadsheet. It is a continuity of families extending backward and forward across time, anchored in real places, marked by real graves, lived in real homes.

Burial is the most powerful marker of lineage continuity because it represents permanence. When generations of a family are buried in a place, the relationship between people and land is not temporary. It is intergenerational. The dead cannot relocate. They remain. Their presence anchors continuity physically. This creates a moral relationship between past, present, and future inhabitants — a relationship existing independently of administrative systems. The state may regulate land. It cannot manufacture the moral continuity burial establishes.

The villages, towns, and cities of England were not created by modern administrative policy. They emerged historically through centuries of human settlement. Families lived there, worked there, died there, were buried there. The state governs these places. It did not create their historical continuity. It inherited jurisdiction over something already in existence. And inherited jurisdiction does not confer original ownership.

GDP growth, labour supply, and fiscal balancing are administrative concerns. Lineage continuity is a civilisational concern. They operate at different constitutional levels entirely. Administrative convenience cannot justify interference with civilisational continuity any more than it could justify abolishing elections permanently for efficiency. Not everything falls within the legitimate scope of optimisation. Some things are simply not the state's to optimise.

The Visceral Wound They Diagnose as Pathology

There is a reason ordinary English, Scottish, Welsh, and Irish people reach for words like invaded when they describe what has happened to their communities. The word is not precise. It is not measured. It is not the language of a constitutional treatise. But it is honest — and the fury behind it deserves to be understood rather than pathologised.

When a man whose grandfather worked the same factory, drank in the same pub, and was buried in the same churchyard finds himself a stranger in the town where four generations of his family lived and died, he is not experiencing a policy disagreement. He is experiencing a rupture in the fabric of his existence across time. It is spiritual. It is temporal. It is visceral. It lives in the gut, not the intellect — the sick, disorienting sensation of recognising nothing where everything was once familiar, of being unmoored from the only continuity he ever possessed.

The political and media class has spent decades slandering this distress as racism, xenophobia, or psychological deficiency — treating it as a disorder to be diagnosed rather than a grievance to be heard. A working-class woman in Rotherham or a retired miner in the Welsh valleys who says she feels like a foreigner in her own town is not displaying ignorance. She is articulating, in the only language available to her, a constitutional injury the educated class lacks the honesty or the courage to name. She is describing the experience of having her inheritance altered without her consent by people who will never live with the consequences.

This is not bigotry. It is grief. It is the grief of dispossession — not of property, but of continuity itself. And it is felt with equal force whether the person experiencing it is English, Scottish, Welsh, or Irish, because lineage is not an English peculiarity. It is a human universal. Every people on earth possesses it. Every people on earth would feel the same wound if the same thing were done to them. The Chinese would feel it. The Koreans would feel it. The Botswanans would feel it. The idea the peoples of these islands are uniquely forbidden from feeling it — uniquely obliged to watch their inherited continuity be redesigned by administrative fiat and say nothing — is itself a species of contempt so profound it should take the breath away.

The elevated rhetoric and the venom are not symptoms of pathology. They are symptoms of a people denied any legitimate vocabulary in which to express a legitimate constitutional grievance. When every measured objection is met with accusations of bigotry, when every quiet concern is dismissed as nostalgia or ignorance, when the only permitted response to the dissolution of inherited continuity is grateful silence — then the language will inevitably become raw, furious, and uncontrolled. Not because the people speaking are uncivilised. But because civilised channels of redress have been systematically closed to them.

A political class which deliberately breaks the lineage of its own people and then criminalises the resulting anguish has not merely exceeded its constitutional warrant. It has added insult to injury on a civilisational scale.

At Which Court Do We Present Our Grievance?

In law, every claim must answer three questions.

- Before which court is the claim made?

- By what authority does the claimant appear?

- And what warrant does the claimant possess to act?

When a representative acts adversarially against those he represents — when the trustee empties the vault, when the guardian harms the ward — to which court does the injured party submit the grievance?

In English constitutional history, the answer has always been the same, and it has always been extraordinary. The English do not appeal to a higher sovereign, because their tradition recognises none above the constitution itself.

- When King John overreached, the barons answered with Magna Carta — not a petition to a foreign prince, but a reassertion of inherited constitutional limits.

- When Charles I broke faith with Parliament, the Petition of Right was issued — a formal constitutional complaint against the sovereign himself, framed not as rebellion but as enforcement of existing law.

- When James II violated his constitutional obligations so thoroughly he could no longer be tolerated, Parliament declared he had abdicated by his own conduct. His authority was not seized. It was declared forfeit.

The English tradition treats authority as conditional upon fidelity to inherited continuity. No officeholder is above the constitutional order. Not the King. Not Parliament. Not any minister, however grand his majority.

But there is a court higher still — one convened not by statute but by the structure of political legitimacy itself. Call it the Court of Time. Its bench is composed of three parties: the dead, who transmitted the inheritance; the living, who temporarily administer it; and the unborn, who possess an equitable claim to receive it intact. No government can escape its jurisdiction, because every political act affects continuity across generations. And in this court, the question is not whether the state acted lawfully. It is whether the state acted within its warrant. Stewards preserve. Proprietors dispose. Only the former possesses legitimate title.

The British political class stands before this court now, and it does not possess the answer it needs.

The Paradox: Your Enemies Share Your Lineage

Here is one of the deepest truths about lineage — and one the political class, in its eagerness to dissolve continuity, has either forgotten or deliberately obscured.

Lineage does not eliminate political conflict. It makes political conflict legitimate.

Consider the paradox. A fascist party and a communist party may despise one another with every fibre of their being. Their visions for the future may be irreconcilable. Yet both parties, if composed of members sharing the same generational continuity, possess something fundamental in common: standing.

They share the lineage to argue on the same ground. Their dispute is legitimate precisely because they are participants in the same inherited chain. They are quarrelling over the future of something they both received from the same ancestors.

This is why civil wars are civil — the word is not accidental. Internal political conflict occurs within a shared continuity. Both sides claim legitimacy based on their relationship to the same inherited political community. One side may vote to break lineage. Another may vote to institutionalise it. But both attempt to legislate something over which they possess genuine jurisdiction, because their authority to participate derives from shared inheritance.

Remove this shared continuity, and political conflict ceases to be deliberation. It becomes merely the exercise of force between disconnected groups — not a family quarrel, but an occupation. Without lineage, there is no enduring political subject. There are only temporary aggregates, managed by administrators, held together not by inheritance but by paperwork.

Parliament itself is an institutionalisation of lineage-based jurisdiction. Its authority derives from representing a continuous political community across time. When it presumes to dissolve the continuity upon which its own legitimacy rests, it is sawing off the branch it sits on.

The Passenger Who Seized the Wheel

There is a final philosophical argument — perhaps the most devastating of all — which removes the question from politics entirely and places it in the domain of ontology. Of what the state is, rather than what anyone wants it to be.

The state has no parents. It has no ancestors. It has no lineage of its own. It is an artificial institution, created by human beings, possessing only those powers delegated to it by the living continuity of the nation. Its agency is not original. It is derivative.

Families produce the state. The state does not produce families.

Friedrich Hayek described the distinction between spontaneous orders and constructed orders. Spontaneous orders — languages, markets, cultures, nations — emerge organically through human interaction across centuries. Constructed orders — bureaucracies, regulations, government departments — are deliberately designed. Nations are spontaneous orders. They cannot be redesigned from above without fundamentally destroying the quality which makes them what they are. The state is a constructed order operating within a spontaneous order, and its authority exists within limits imposed by the organic reality from which it draws its legitimacy.

Even the appalling Marx — no conservative, no traditionalist — recognised this structural constraint. "Men make their own history," he wrote, "but they do not make it as they please." History emerges from accumulated human activity under inherited conditions. It is not infinitely malleable. Political authority operates within historical constraints it did not create and cannot fully override without destroying its own foundations.

The Burkean conservative, the Lockean liberal, the republican theorist, and the Marxist historical materialist disagree on nearly everything. But they converge on one shared premise: the state is not morally unlimited in its authority over the continuity of human life across time.

Burke calls it trusteeship. Locke calls it protection of inheritance. Republicans call it non-domination. Marx calls its violation alienation — the severing of human beings from their historical continuity, turned into strangers in the world they inhabit.

When Andrew Neather described the desire to "rub the Right's nose in diversity," he was not describing immigration policy. He was describing alienation — the deliberate, state-directed severance of a people from their inherited continuity for political advantage. And this is not an accusation confined to one party. Both Labour and Conservative governments have presided over levels of demographic transformation unprecedented in these islands since the Norman Conquest — carried out not through invasion, but through the far more insidious mechanism of administrative fiat for GDP, exercised by people who possessed the keys to the vault but never owned its contents.

The Warrant They Never Had

To claim authority over the generational continuity of the British people, the state would need to demonstrate one of three things.

- First, it could claim it created the British nation. This is historically false. The nation preceded the state by centuries.

- Second, it could claim it owns the British nation. This is constitutionally false. The state is a custodian, not a proprietor, and eight centuries of English constitutional development affirm this beyond serious dispute.

- Third, it could claim future generations possess no equitable interest in receiving their inheritance intact. This is morally untenable. Burke's unborn are silent, but they are not without claim.

None of these positions can be sustained. Not one. And without them, the claim of unlimited authority over national continuity collapses — not on grounds of policy preference, not on grounds of sociology, not on grounds of racial theory, but on the coldest, hardest ground of all: the absence of constitutional title.

The British state governs a continuity it did not create. It inherited jurisdiction over a chain of generational transmission stretching back beyond the reach of recorded history. It arrived as a passenger aboard a vessel already in motion — built by hands long dead, sailing toward shores the unborn will one day stand upon. The state may steer. It may maintain the hull. It may adjust the sails when necessity demands.

But it does not own the ship.

It never did.

And no amount of GDP projections, labour-market reports, fiscal impact studies, or technocratic hand-waving can manufacture the title it lacks. Because this is not a question of economics. It is not a question of efficiency. It is not a question amenable to spreadsheet resolution.

It is the oldest question in English constitutional law.

By what right?

The churchyard does not submit its accounts to the Treasury. The chain of grandmothers stretching backward through the centuries does not require authorisation from the Home Office to exist. These things are older than the state, more enduring than any government, and more real than any administrative category yet devised by Whitehall.

When the state presumes to break this chain — not through the honest accidents of history, not through the organic movement of peoples across millennia, but through deliberate policy designed in committee rooms by temporary officeholders pursuing administrative objectives — it commits an act for which there is a precise constitutional term.

Beyond its powers. Beyond its warrant. Beyond its title.

You don't have the right to break our lineage.

You never did.

And we are no longer willing to pretend otherwise.